-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2012; 2(4): 34-37

doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20120204.02

The HAPU Bundle: A Tool to Reduce the Incidence of Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcers in the Intensive Care Unit

Gerardo Carino 1, 2, Donna Ricci 1, Deborah Bartula 1, Elizabeth Manzo 1, 2, Jennifer Sargent 1

1Department Critical Care Medicine, The Miriam Hospital, City, Providence, RI 02906, USA

2Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Warren Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University Providence, RI, 02906, USA

Correspondence to: Gerardo Carino , Department Critical Care Medicine, The Miriam Hospital, City, Providence, RI 02906, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers remain a large problem in hospitalized patients, most often developing in critically-ill patients in intensive care units. Extensive guidelines exist to assist in the prevention and care of pressure ulcers, however the individual recommendations are numerous and it is very unclear as to their relative importance. We reviewed these recommendations and developed a short list of 6 that we rigorously implemented and audited in our mixed surgical and medical ICU using an interdisciplinary team of physicians, nurses and dieticians. We termed these 6 indicators the hospital acquired pressure ulcer bundle, or HAPU Bundle. With one year of broad utilization of these bundles, we were able to reduce the incidence of hospital-acquired pressure ulcers in our ICU from 12.4% to 6.1%. The HAPU bundle may prove to be an easy to use and practical tool to help apply evidence-based guidelines and reduce pressure ulcers in the highest risk patients.

Keywords: Pressure Ulcers, Care Bundles, Quality Improvement

Cite this paper: Gerardo Carino , Donna Ricci , Deborah Bartula , Elizabeth Manzo , Jennifer Sargent , "The HAPU Bundle: A Tool to Reduce the Incidence of Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcers in the Intensive Care Unit", International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 2 No. 4, 2012, pp. 34-37. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20120204.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Pressure ulcers are a significant problem in hospitalized patients. Critically-ill patients in intensive care units are at highest risk for the development of new pressure ulcers during their stay. The prevalence of pressure ulcers in critical care has been reported at 22% while the incidence ranged from 8-40%[1]. Severe pressure ulcers (stage 3 and 4) are now considered “never events” by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Unfortunately, hospital-acquired pressure ulcers (HAPUs) continue to occur with resultant significant morbidity and mortality for patients and increased costs for the health care system. These HAPUs may be avoidable when significant preventative efforts are performed consistently.Multiple published guidelines from government and professional groups for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers are available. Most recently, the U.S. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panels published evidence-based recommendations[2]. These guidelines emphasize patient risk-stratification and identification, avoidance of pressure, patient mobility, improvement of nutrition and underlying disease state and the utilization of specialty surfaces. However, the actual recommendations are numerous (numbering over 100) and it is unclear as to the relative importance of each recommendation. In addition, specific implementation strategies are lacking. As such, the development of a simple, straight-forward process leading to reduction of pressure ulcers would be extremely desirable.Care bundles have been used extensively in health care to accomplish measurable improvements in multiple conditions, including, but not limited to, ventilator-acquired pneumonia, catheter-related blood stream infections and sepsis[3-5]. In general, bundles are groupings of best practices for prevention or management of a specific entity that result in greater improvement when applied together than when each intervention is applied individually. Ideally, each of the components of a bundle would be based on an evidence-based intervention know clearly to have a beneficial outcome.The goal of this project was to develop a relatively simple “HAPU Bundle” based on the various evidence-based guidelines and then apply them to a critically-ill patient population as part of a quality-improvement project.

2. Methods

- Evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of hospital-acquired pressure ulcers were reviewed and discussed extensively in order to establish the HAPU Bundle. The authors met multiple times and discussed each individual recommendation put forth in the U.S. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panels. By consensus, six measures were identified and chosen as clearly important, able to regularly implement and measure and most likely to lead to success in prevention of pressure ulcers. These measures are shown in Table 1 and the following paragraphs describe some of the supporting data and rationale.

2.1. Daily Skin Assessment

- Current guidelines for pressure ulcer prevention recommend risk assessment for all patients. The Braden Score is widely used as an assessment tool by nurses and has been shown to be effective in reducing pressure ulcer prevention[6]. This has long been utilized in our facility by nursing to assess all patients. However, regular skin assessment by the physician team was not standard of care for patients in the ICU. As part of this intervention and with the goal of incorporating an interdisciplinary approach to pressure ulcer care and prevention, documentation of skin exam by the physician staff was added as one of the components of the HAPU bundle.

2.2. Regular Repositioning

- As prolonged exposure to pressure is the primary cause of a pressure ulcer, any primary intervention to prevent pressure ulcers needs to minimize continuous pressure. Healthy people are able to regularly reposition their bodies, both while awake and asleep, to minimize pressure and damage. Acutely or chronically-ill patients may lose this ability and with prolonged immobility are at increased risk of developing pressure ulcers. A number of studies have suggested the benefit of regular repositioning, however the optimal frequency and technique for repositioning has not been clearly described. Repositioning every 2 hours, every 3 hours, every 4 hours or even on a rotation schedule have all been proposed as appropriate[7]. We have selected q2hr rotation as our standard and this was used in our HAPU bundle. Failure with this measure would occur with even one missed documented turn in a 24 hour period.

2.3. Nutrition Assessment

- Current guidelines state that all patients should have a nutritional assessment, preferably with the measurement of a nutritional laboratory parameter. A few parameters have been found to be correlated with pressure ulcer development, including prealbumin, total protein, serum albumin, and transferring and that most patients to develop severe pressure ulcers have a measurable nutritional deficiency[8]. The decision was made to measure prealbumin on admission to the ICU and every 7 days of the ICU stay as part of the bundle.

2.4. Calorie Intake

- A large percentage of critically ill patients, possibly approaching 50%, are malnourished and are clearly at increased risk to develop pressure ulcers[9]. Even with feeding protocols, patients frequently do not receive the prescribed daily calories due to a number of reasons including tube feed intolerance, inability to swallow, disease state and stopping due to diagnostic tests[10]. In line with the current recommendations to measure and document delivered calories, all patients had daily calorie counts and were the achievement of 75% of their daily calorie goal was included on the bundle.

2.5. Glucose Control

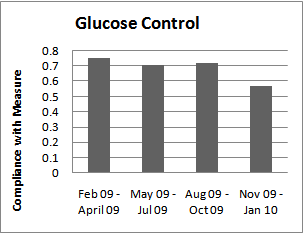

- A large number of underlying co-morbidities or patient-center risk factors are associated with poor wound healing, decreased tissue integrity and overall increased riskof pressure ulcers. The list includes, but is not limited to, malignancy, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, paralysis, peripheral vascular disease and smoking. Diabetes with hyperglycemia is one of the few disease processes that can be modulated closely in the acute setting. Appropriate blood sugar control in the ICU has been clearly associated with improved outcome, so this measure has also been included in our bundle[11]. The first morning glucose measured was documented, with a level <150 mg/dL defined as meeting the indicator.

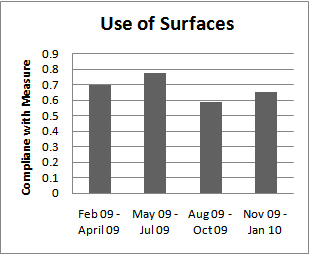

2.6. Redistribution Surfaces

- A large number of surfaces designed to minimize pressure and shear are available and are recommended for use in high risk patients or with a history of pressure ulcer[12]. A low shear and air-loss overlay mattress was utilized in our unit and then provided for patients deemed high risk. The utilization of this surface was included in the bundle.

2.7. Data Collection

- The HAPU bundles were audited 2 times per week starting in February of 2008 for 12 months. This audit was conducted by the same investigator (EM) in order to minimize variation in the data collection. Data collection occurred on different weekday afternoons only and the ICU care team did not have knowledge as to when the data collection would occur. Data regarding the prevalence of hospital-acquired pressure ulcers was obtained during this time period and retrospectively for the 12 months previous to the initiation of the HAPU bundle utilizing the hospitals’ Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Database. This data has been collected separately in our facility for many years as part of the hospitals’ quality program and not solely as part of this research project. Prevalence is measured by trained nurses on the third Friday of each month when all patients are examined for pressure ulcers. Standard HAPU prevention strategies were utilized in all critically-ill patients throughout the study both before and after the introduction of these HAPU bundles.

3. Results and Discussion

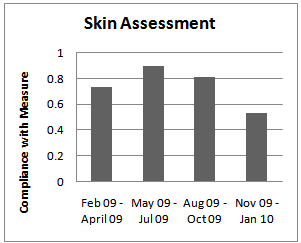

| Figure 1. Skin Assessment Audit |

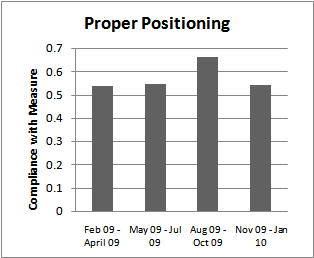

| Figure 2. Positioning Audit |

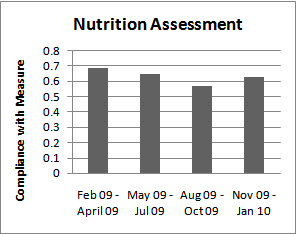

| Figure 3. Nutrition Assessment Audit |

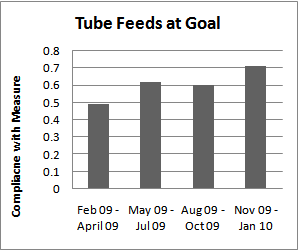

| Figure 4. Tube Feed Audit |

| Figure 5. Glucose Control Audit |

| Figure 6. Use of Redistribution Surfaces Audit |

4. Conclusions

- The prevalence of HAPUs in ICUs continues to be high and there are multiple factors associated with increased risk. Current recommendations are very extensive and difficult to implement as a whole. By creating and implementing a HAPU bundle that incorporates a small number of interventions known to decrease HAPUs and auditing its use, the rates of HAPU in the ICU can be reduced. Even with imperfect compliance with our HAPU bundle, we were able to reduce our prevalence from 12.4 to 6.1%. There remains room for improvement in the implementation and adherence to these HAPU bundles that we describe and we certainly do not want to suggest that they can take the place of the remaining pressure ulcer prevention recommendations. However, this HAPU bundle may be a useful and practical tool in obtaining further reductions in hospital-acquired pressure ulcers and are a clear indication that a multidisciplinary approach is needed for success.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to acknowledge the staff of the Miriam Hospital Intensive Care Unit who contributed greatly to this project.This project was approved by the Miriam Hospital Institutional Research Review Board.

References

| [1] | Kaitani T, Tokunaga, K Matsui, N et al. Risk Factors Related to the Development of Pressure Ulcers in the Critical Care Setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2010; 19: 414-421 |

| [2] | Association for the Advancement of Wound Cae (AAWC) Guideline of Pressure Ulcer Guidelines. Malvern, Pennsylvania: Association for the Advancement of Wound Care (AAWC) 2010 |

| [3] | Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz, S, et al. An Intervention to Decrease Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in the ICU. NEJM 2006; 355(26): 2725-2732 |

| [4] | Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines for Management of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Intensive Care Medicine 2004; 30(4)536-555 |

| [5] | Wip C and Napolitano, L. Bundles to Prevent Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: How Valuable are They? Curr Opin in Infect Dis 2009; 22:159-166 |

| [6] | Comfort, E. Reducing Pressure Ulcer Incidence through Braden Scale Risk Assessment and Support Surface Use. Adv Skin Wound Care 2008; 21:330-4 |

| [7] | Krapfl LE, Gray M. Does Regular Repositioning Prevent Pressure Ulcers. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2008; 35(6): 571-577 |

| [8] | Guenter P, Malyszek R, Bliss DZ et al. Survey of Nutritional Status in Newly Hospitalized Patients with Stage III or Stage IV Pressure Ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care 2000; 13(4): 164-8 |

| [9] | Quirk J. Malnutrition in Critically Ill Patients in Intensive Care Units. British Journal of Nursing 2000; 9(9):537-41 |

| [10] | Heyland DK, Cahill NE, Dhaliwal R, et al. Impact of Enteral Feeding Protocols on Enteral Nutrition Delivery, Results of a Multicenter Observational Study. JPEN 2010; 34: 675-684 |

| [11] | NICE-SUGAR Investigators. Intensive versus Conventional Glucose Control in Critically Ill Patients. NEJM 2009; 360(13): 1283-1297 |

| [12] | Pemberton V, Turner V, VanGuilder C. The Effect of Using a Low-Air-Loss Surface on the Skin Integrity of Obese Patients: Results of a Pilot Study. Ostomy Wound Management 2009; 55(2): 44-8 |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML