| [1] | Repins, I., Contreras, M. A., Egaas, B., DeHart, C., Scharf, J., Perkins, C. L., ... & Noufi, R. (2008). 19· 9%-efficient ZnO/CdS/CuInGaSe2 solar cell with 81· 2% fill factor. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and applications, 16(3), 235-239. |

| [2] | Tsukazaki, A., Ohtomo, A., Onuma, T., Ohtani, M., Makino, T., Sumiya, M., ... & Kawasaki, M. (2005). Repeated temperature modulation epitaxy for p-type doping and light-emitting diode based on ZnO. Nature materials, 4(1), 42-46. |

| [3] | Lee, K. M., Lai, C. W., Ngai, K. S., & Juan, J. C. (2016). Recent developments of zinc oxide based photocatalyst in water treatment technology: a review. Water research, 88, 428-448. |

| [4] | Chen, X., Wu, Z., Liu, D., & Gao, Z. (2017). Preparation of ZnO photocatalyst for the efficient and rapid photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes. Nanoscale research letters, 12, 1-10. |

| [5] | Ouyang, W., Chen, J., Shi, Z., & Fang, X. (2021). Self-powered UV photodetectors based on ZnO nanomaterials. Applied physics reviews, 8(3). |

| [6] | Patel, M., Song, J., Kim, D. W., & Kim, J. (2022). Carrier transport and working mechanism of transparent photovoltaic cells. Applied Materials Today, 26, 101344. |

| [7] | Lu, L., Li, R., Fan, K., & Peng, T. (2010). Effects of annealing conditions on the photoelectrochemical properties of dye-sensitized solar cells made with ZnO nanoparticles. Solar Energy, 84(5), 844-853. |

| [8] | Lyons, J. L., Janotti, A., & Van de Walle, C. G. (2009). Why nitrogen cannot lead to p-type conductivity in ZnO. Applied Physics Letters, 95(25). |

| [9] | Zhang, Y. G., Zhang, G. B., & Xu Wang, Y. (2011). First-principles study of the electronic structure and optical properties of Ce-doped ZnO. Journal of Applied Physics, 109(6). |

| [10] | Ungula, J., Kiprotich, S., Swart, H. C., & Dejene, B. F. (2022). Investigation on the material properties of ZnO nanorods deposited on Ga-doped ZnO seeded glass substrate: Effects of CBD precursor concentration. Surface and Interface Analysis, 54(10), 1023-1031. |

| [11] | Ungula, J. (2015). Growth and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles by sol-gel process (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Free State (Qwaqwa Campus)). |

| [12] | Aksoy, S., Polat, O., Gorgun, K., Caglar, Y., & Caglar, M. (2020). Li doped ZnO based DSSC: Characterization and preparation of nanopowders and electrical performance of its DSSC. Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems and Nanostructures, 121, 114127. |

| [13] | Lin, C. Y., Lai, Y. H., Chen, H. W., Chen, J. G., Kung, C. W., Vittal, L. R., & Ho, K. C. (2011). Highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cell with a ZnO nanosheet-based photoanode. Energy & Environmental Science, 4(9), 3448-3455. |

| [14] | Quintana, M., Edvinsson, T., Hagfeldt, A., & Boschloo, G. (2007). Comparison of dye-sensitized ZnO and TiO2 solar cells: studies of charge transport and carrier lifetime. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 111(2), 1035-1041. |

| [15] | Freeman, C. L., Claeyssens, F., Allan, N. L., & Harding, J. H. (2006). Graphitic nanofilms as precursors to wurtzite films: theory. Physical review letters, 96(6), 066102. |

| [16] | Freeman, C. L., Claeyssens, F., Allan, N. L., & Harding, J. H. (2006). Graphitic nanofilms as precursors to wurtzite films: theory. Physical review letters, 96(6), 066102. |

| [17] | Tusche, C., Meyerheim, H. L., & Kirschner, J. (2007). Observation of depolarized ZnO (0001) monolayers: formation of unreconstructed planar sheets. Physical review letters, 99(2), 026102. |

| [18] | Weirum, G., Barcaro, G., Fortunelli, A., Weber, F., Schennach, R., Surnev, S., & Netzer, F. P. (2010). Growth and surface structure of zinc oxide layers on a Pd (111) surface. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 114(36), 15432-15439. |

| [19] | He, A. L., Wang, X. Q., Wu, R. Q., Lu, Y. H., & Feng, Y. P. (2010). Adsorption of an Mn atom on a ZnO sheet and nanotube: A density functional theory study. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, 22(17), 175501. |

| [20] | Schmidt, T. M., Miwa, R. H., & Fazzio, A. (2010). Ferromagnetic coupling in a Co-doped graphenelike ZnO sheet. Physical Review B, 81(19), 195413. |

| [21] | Ren, J., Zhang, H., & Cheng, X. (2013). Electronic and magnetic properties of all 3d transition-metal-doped ZnO monolayers. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry, 113(19), 2243-2250. |

| [22] | Zheng, F. B., Zhang, C. W., Wang, P. J., & Luan, H. X. (2012). First-principles prediction of the electronic and magnetic properties of nitrogen-doped ZnO nanosheets. Solid state communications, 152(14), 1199-1202. |

| [23] | Guo, H., Zhao, Y., Lu, N., Kan, E., Zeng, X. C., Wu, X., & Yang, J. (2012). Tunable magnetism in a nonmetal-substituted ZnO monolayer: a first-principles study. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 116(20), 11336-11342. |

| [24] | Zhang, W. X., T. Li, C. He, X. L. Wu, L. Duan, H. Li, L. Xu, and S. B. Gong. "First-principle study on Ag-2N heavy codoped of p-type graphene-like ZnO nanosheet." Solid State Communications 204 (2015): 47-50. |

| [25] | Ungula, J. (2018). Formation and characterization of novel nanostructured un-doped and Ga-doped ZnO transparent conducting thin films for photoelectrode (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Free State (Qwaqwa Campus)). |

| [26] | Omidvar, A. (2018). Indium-doped and positively charged ZnO nanoclusters: versatile materials for CO detection. Vacuum, 147, 126-133. |

| [27] | Khuili, M., El Hallani, G., Fazouan, N., Abou El Makarim, H., & Atmani, E. H. (2019). First-principles calculation of (Al, Ga) co-doped ZnO. Computational Condensed Matter, 21, e00426. |

| [28] | Vettumperumal, R., Kalyanaraman, S., & Thangavel, R. (2015). Optical constants and near infrared emission of Er doped ZnO sol–gel thin films. Journal of Luminescence, 158, 493-500. |

| [29] | Tan, C., Xu, D., Zhang, K., Tian, X., & Cai, W. (2016). Electronic and magnetic properties of rare-earth metals doped ZnO monolayer. Journal of Nanomaterials, 16(1), 356-356. |

| [30] | da Fonseca, A. F. V., Siqueira, R. L., Landers, R., Ferrari, J. L., Marana, N. L., Sambrano, J. R., ... & Schiavon, M. A. (2018). A theoretical and experimental investigation of Eu-doped ZnO nanorods and its application on dye sensitized solar cells. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 739, 939-947. |

| [31] | Chamanzadeh, Z., Ansari, V., & Zahedifar, M. (2021). Investigation on the properties of La-doped and Dy-doped ZnO nanorods and their enhanced photovoltaic performance of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Optical Materials, 112, 110735. |

| [32] | Tan, C., Xu, D., Zhang, K., Tian, X., & Cai, W. (2016). Electronic and magnetic properties of rare-earth metals doped ZnO monolayer. Journal of Nanomaterials, 16(1), 356-356. |

| [33] | Mary, J. A., Vijaya, J. J., Dai, J. H., Bououdina, M., Kennedy, L. J., & Song, Y. (2015). Experimental and DFT studies of structure, optical and magnetic properties of (Zn1− 2xCexCox) O nanopowders. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1084, 155-164. |

| [34] | Wen, J. Q., Zhang, J. M., Chen, G. X., Wu, H., & Yang, X. (2018). The structural, electronic and optical properties of Nd doped ZnO using first-principles calculations. Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems and Nanostructures, 98, 168-173. |

| [35] | Khuili, M., Fazouan, N., Abou El Makarim, H., Atmani, E. H., Rai, D. P., & Houmad, M. (2020). First-principles calculations of rare earth (RE= Tm, Yb, Ce) doped ZnO: Structural, optoelectronic, magnetic, and electrical properties. Vacuum, 181, 109603. |

| [36] | Nekvindova, P., Cajzl, J., Mackova, A., Malinský, P., Oswald, J., Boettger, R., & Yatskiv, R. (2020). Er implantation into various cuts of ZnO–experimental study and DFT modelling. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 816, 152455. |

| [37] | Zhang, F., Gan, Q., Yan, M., Cui, H., Zhang, H., Chao, D., ... & Zhang, W. (2016). The first-principles study of electronic structures, magnetic and optical properties for Ce-doped ZnO. Integrated Ferroelectrics, 172(1), 87-96. |

| [38] | Wen, J. Q., Han, Y. S., Yang, X., & Zhang, J. M. (2019). Computational research of electronic, optical and magnetic properties of Ce and Nd co-doped ZnO. Journal Of Physics And Chemistry Of Solids, 125, 90-95. |

| [39] | Mulwa, W. M., Ouma, C. N., Onani, M. O., & Dejene, F. B. (2016). Energetic, electronic and optical properties of lanthanide doped TiO2: An ab initio LDA+ U study. Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 237, 129-137. |

| [40] | Agapito, L. A., Curtarolo, S., & Nardelli, M. B. (2015). Reformulation of DFT+ U as a pseudohybridhubbard density functional for accelerated materials discovery. Physical Review X, 5(1), 011006. |

| [41] | Deng, X. Y., Liu, G. H., Jing, X. P., & Tian, G. S. (2014). On-site correlation of p-electron in d10 semiconductor zinc oxide. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry, 114(7), 468-472. |

| [42] | Harun, K., Salleh, N. A., Deghfel, B., Yaakob, M. K., & Mohamad, A. A. (2020). DFT+ U calculations for electronic, structural, and optical properties of ZnO wurtzite structure: A review. Results in Physics, 16, 102829. |

| [43] | S.L. Dudarev, G.A. Botton, S.Y. Savrasov, C.J. Humphreys, A.P. Sutton, Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study, Phys. Rev. B. 57 (1998) 1505–1509. |

| [44] | Cococcioni, M., & De Gironcoli, S. (2005). Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA+ U method. Physical Review B, 71(3), 035105. |

| [45] | Ma, X., Wu, Y., Lv, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2013). Correlation effects on lattice relaxation and electronic structure of ZnO within the GGA+ U formalism. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 117(49), 26029-26039. |

| [46] | Huang, G. Y., Wang, C. Y., & Wang, J. T. (2012). Detailed check of the LDA+ U and GGA+ U corrected method for defect calculations in wurtzite ZnO. Computer Physics Communications, 183(8), 1749-1752. |

| [47] | Jain, A., Montoya, J., Dwaraknath, S., Zimmermann, N. E., Dagdelen, J., Horton, M., ... & Persson, K. (2020). The materials project: Accelerating materials design through theory-driven data and tools. Handbook of Materials Modeling: Methods: Theory and Modeling, 1751-1784. |

| [48] | Giannozzi, P., Baroni, S., Bonini, N., Calandra, M., Car, R., Cavazzoni, C., &Wentzcovitch, R. M. (2009). QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. Journal of physics: Condensed matter, 21(39), 395502. |

| [49] | Perdew, J. P., Burke, K., & Ernzerhof, M. (1996). Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Physical review letters, 77(18), 3865. |

| [50] | Kohn, W., & Sham, L. J. (1965). Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Physical review, 140(4A), A1133. |

| [51] | Solola, G. T., Bamgbose, M. K., Adebambo, P. O., Ayedun, F., & Adebayo, G. A. (2023). First-principles investigations of structural, electronic, vibrational, and thermoelectric properties of half-Heusler VYGe (Y= Rh, Co, Ir) compounds. Computational Condensed Matter, e00827. |

| [52] | Monkhorst, H. J., & Pack, J. D. (1976). Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Physical review B, 13(12), 5188-5192. |

| [53] | Motornyi, O., Raynaud, M., Dal Corso, A., & Vast, N. (2018, December). Simulation of electron energy loss spectra with the turboEELS and thermo_pw codes. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1136, No. 1, p. 012008). IOP Publishing. |

| [54] | Litim, D. F., & Manuel, C. (2002). Semi-classical transport theory for non-Abelian plasmas. Physics reports, 364(6), 451-539. |

| [55] | Madsen, G. K., & Singh, D. J. (2006). BoltzTraP. A code for calculating band-structure dependent quantities. Computer Physics Communications, 175(1), 67-71. |

| [56] | Topsakal, M., Cahangirov, S., Bekaroglu, E., & Ciraci, S. (2009). First-principles study of zinc oxide honeycomb structures. Physical Review B, 80(23), 235119. |

| [57] | Tan, C., Sun, D., Xu, D., Tian, X., & Huang, Y. (2016). Tuning electronic structure and optical properties of ZnO monolayer by Cd doping. Ceramics International, 42(9), 10997-11002. |

| [58] | Momma, K., & Izumi, F. (2011). VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. Journal of applied crystallography, 44(6), 1272-1276. |

| [59] | Fang, D. Q., Rosa, A. L., Zhang, R. Q., & Frauenheim, T. (2010). Theoretical exploration of the structural, electronic, and magnetic properties of ZnO nanotubes with vacancies, antisites, and nitrogen substitutional defects. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 114(13), 5760-5766. |

| [60] | Tu, Z. C. (2010). First-principles study on physical properties of a single ZnO monolayer with graphene-like structure. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience, 7(6), 1182-1186. |

| [61] | Tan, C., Sun, D., Tian, X., & Huang, Y. (2016). First-principles investigation of phase stability, electronic structure and optical properties of MgZnO monolayer. Materials, 9(11), 877. |

| [62] | Haq, B. U., AlFaify, S., Alrebdi, T. A., Ahmed, R., Al-Qaisi, S., Taib, M. F. M., ... & Zahra, S. (2021). Investigations of optoelectronic properties of novel ZnO monolayers: A first-principles study. Materials Science and Engineering: B, 265, 115043. |

| [63] | Abderrahmane, B., Djamila, A., Chaabia, N., & Fodil, R. (2020). Improvement of ZnO nanorods photoelectrochemical, optical, structural and morphological characterizations by cerium ions doping. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 829, 154498. |

| [64] | Ullah Awan, S., Hasanain, S. K., Bertino, M. F., & Hassnain Jaffari, G. (2012). Ferromagnetism in Li doped ZnO nanoparticles: The role of interstitial Li. Journal of Applied Physics, 112(10). |

| [65] | Bett, K., & Kiprotich, S. (2024). Effects of Stirring Speed of Precursor Solution on the Structural Optical and Morphological Properties of ZnO Al Ga CoDoped Nanoparticles Synthesized via a Facile Sol Gel Technique. |

| [66] | Ungula, J. (2015). Growth and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles by sol-gel process (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Free State (Qwaqwa Campus)). |

| [67] | Jantrasee, S., Moontragoon, P., & Pinitsoontorn, S. (2016). Thermoelectric properties of Al-doped ZnO: experiment and simulation. Journal of Semiconductors, 37(9), 092002. |

| [68] | Papadimitriou, D. N. (2022). Engineering of optical and electrical properties of electrodeposited highly doped Al: ZnO and In: ZnO for cost-effective photovoltaic device technology. Micromachines, 13(11), 1966. |

| [69] | El Hachimi, A. G., Zaari, H., Benyoussef, A., El Yadari, M., & El Kenz, A. (2014). First-principles prediction of the magnetism of 4f rare-earth-metal-doped wurtzite zinc oxide. Journal of rare earths, 32(8), 715-721. |

| [70] | Wu, Q., Liu, G., Shi, H., Zhang, B., Ning, J., Shao, T., ... & Zhang, F. (2023). Impact of Nd doping on electronic, optical, and magnetic properties of ZnO: A GGA+ U study. Molecules, 28(21), 7416. |

| [71] | Deng, S. H., Duan, M. Y., Xu, M., & He, L. (2011). Effect of La doping on the electronic structure and optical properties of ZnO. Physica B: Condensed Matter, 406(11), 2314-2318. |

| [72] | Meulenkamp, E. A. (1999). Electron transport in nanoparticulate ZnO films. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 103(37), 7831-7838. |

| [73] | Wang, B., Nagase, S., Zhao, J., & Wang, G. (2007). The stability and electronic structure of single-walled ZnO nanotubes by density functional theory. Nanotechnology, 18(34), 345706. |

| [74] | Namisi, M. M., Musembi, R. J., Mulwa, W. M., &Aduda, B. O. (2023). DFT study of cubic, tetragonal and trigonal structures of KGeCl3 perovskites for photovoltaic applications. Computational Condensed Matter, 34, e00772. |

| [75] | Harun, K., Salleh, N. A., Deghfel, B., Yaakob, M. K., & Mohamad, A. A. (2020). DFT+ U calculations for electronic, structural, and optical properties of ZnO wurtzite structure: A review. Results in Physics, 16, 102829. |

| [76] | Berrezoug, H. I., Merad, A. E., Zerga, A., & Hassoun, Z. S. (2015). Simulation and modeling of structural stability, electronic structure and optical properties of ZnO. Energy Procedia, 74, 1517-1524. |

| [77] | Solola, G. T., Bamgbose, M. K., Adebambo, P. O., Ayedun, F., & Adebayo, G. A. (2023). First-principles investigations of structural, electronic, vibrational, and thermoelectric properties of half-Heusler VYGe (Y= Rh, Co, Ir) compounds. Computational Condensed Matter, e00827. |

and

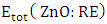

and  are the total energies per supercell of the relaxed RE doped and undoped ZnO respectively. The

are the total energies per supercell of the relaxed RE doped and undoped ZnO respectively. The  and

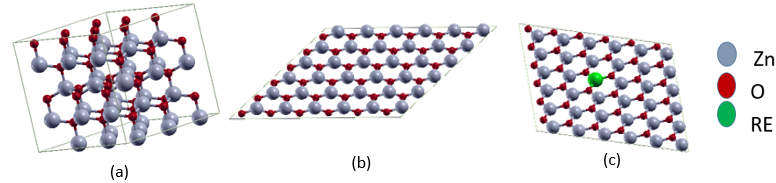

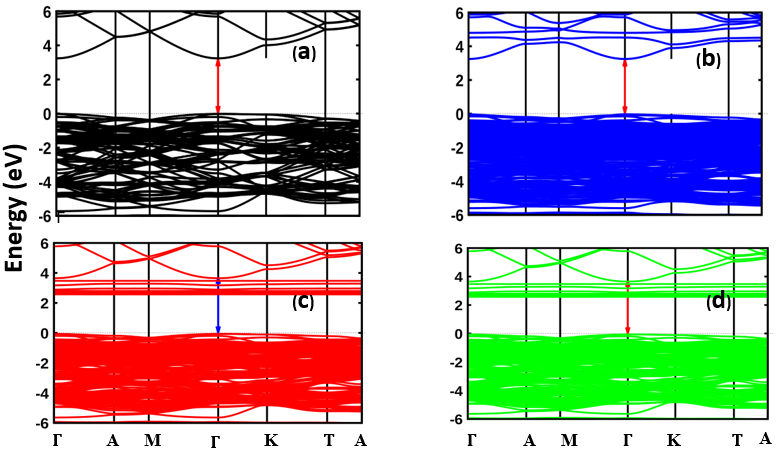

and  represent the chemical potential of Zn and RE (Ce, Dy and Eu) respectively which is presumably the energy per atom in their respective metals. Ef is utilized as a stability metric, where a negative Ef indicates enhanced structural stability [61,62], thereby rendering the corresponding compound more desirable for experimental purposes. A plot of the obtained Ef is presented in figure 2 showing that the Ef of all RE doped M-ZnO tested was negative. This indicates that the doping process is thermodynamically and chemically favorable for each of these RE elements in the M- ZnO crystal lattice. The negative formation energy suggests that when Ce, Dy, or Eu atoms are incorporated into ZnO, the overall energy of the system decreases, making the RE doped M-ZnO structure more stable than the undoped ZnO.

represent the chemical potential of Zn and RE (Ce, Dy and Eu) respectively which is presumably the energy per atom in their respective metals. Ef is utilized as a stability metric, where a negative Ef indicates enhanced structural stability [61,62], thereby rendering the corresponding compound more desirable for experimental purposes. A plot of the obtained Ef is presented in figure 2 showing that the Ef of all RE doped M-ZnO tested was negative. This indicates that the doping process is thermodynamically and chemically favorable for each of these RE elements in the M- ZnO crystal lattice. The negative formation energy suggests that when Ce, Dy, or Eu atoms are incorporated into ZnO, the overall energy of the system decreases, making the RE doped M-ZnO structure more stable than the undoped ZnO.

and

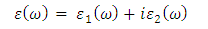

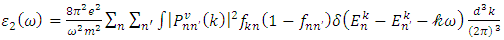

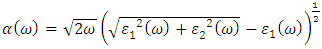

and  are the real and complex parts respectively of the complex dielectric functions. While the real part, explains the photon dispersion and extent of material polarisation, the imaginary component describes the photon absorption of a material. The calculations of momentum matrix elements, as described in equation 3, yields the imaginary component when considering transitions between unoccupied and occupied wavefunctions

are the real and complex parts respectively of the complex dielectric functions. While the real part, explains the photon dispersion and extent of material polarisation, the imaginary component describes the photon absorption of a material. The calculations of momentum matrix elements, as described in equation 3, yields the imaginary component when considering transitions between unoccupied and occupied wavefunctions  [75].

[75].

from

from  [75].

[75].

and

and  as described in equations 5-8.

as described in equations 5-8.

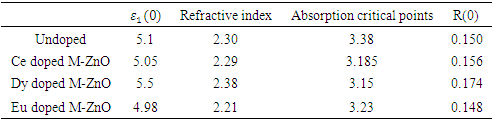

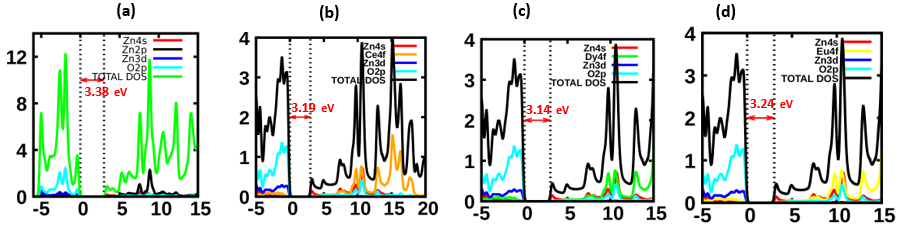

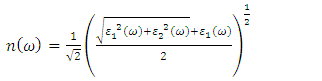

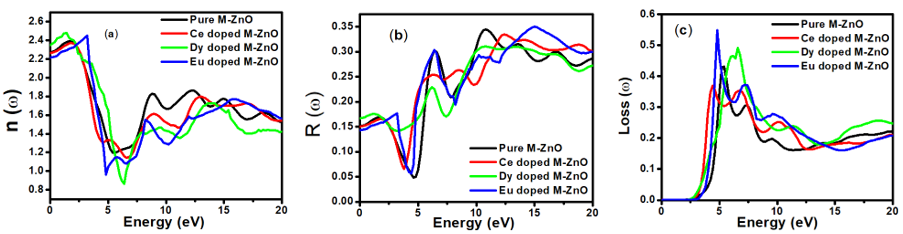

is presented for pure M-ZnO alongside RE (Ce, Dy and Eu) doped M-ZnO. As demonstrated in Table 2, the refractive indices were derived by applying the square root to these values [74]. From this table, the Dy doped M-ZnO has the highest

is presented for pure M-ZnO alongside RE (Ce, Dy and Eu) doped M-ZnO. As demonstrated in Table 2, the refractive indices were derived by applying the square root to these values [74]. From this table, the Dy doped M-ZnO has the highest  as well as the refractive index. The imaginary spectrum characterizes the correlation between the optical and electronic attributes of a given material. From figure 7(b) of

as well as the refractive index. The imaginary spectrum characterizes the correlation between the optical and electronic attributes of a given material. From figure 7(b) of  as a function of energy, the critical onset points are located at 3.37, 3.18,3.15 and 3.24 eV for pure, Ce, Dy and Eu doped M-ZnO compounds respectively. The values are consistent with the energy band gaps derived from band structure calculations. Three main peaks at approximately 5.2, 8.1 and 15.5 eV for all the compounds tested were observed on

as a function of energy, the critical onset points are located at 3.37, 3.18,3.15 and 3.24 eV for pure, Ce, Dy and Eu doped M-ZnO compounds respectively. The values are consistent with the energy band gaps derived from band structure calculations. Three main peaks at approximately 5.2, 8.1 and 15.5 eV for all the compounds tested were observed on  plot resulting from the transition of an electron from the valence to the conduction band. The absorption coefficient reflects the extent to which light intensity declines per unit distance in a material medium. The photon frequency significantly influences this parameter, indicating that the incident photon interacts with the electrons within the material, which facilitates inter-band transition from the valence to conduction bands. According to Figure 7(c), absorption edge of M-ZnO was observed at 3.38, 3.185, 3.15 and 3.23 eV for the pure, Ce, Dy and Eu doped M-ZnO compounds respectively as presented in Table 2. The analysis shows that M-ZnO allows the majority of visible light of the solar radiation to pass through, which is a critical requirement for its function as a photoanode in DSSCs. Therefore, M-ZnO effectively transmits light to the absorption dye, enabling photoemission and the generation of electrical current [76].

plot resulting from the transition of an electron from the valence to the conduction band. The absorption coefficient reflects the extent to which light intensity declines per unit distance in a material medium. The photon frequency significantly influences this parameter, indicating that the incident photon interacts with the electrons within the material, which facilitates inter-band transition from the valence to conduction bands. According to Figure 7(c), absorption edge of M-ZnO was observed at 3.38, 3.185, 3.15 and 3.23 eV for the pure, Ce, Dy and Eu doped M-ZnO compounds respectively as presented in Table 2. The analysis shows that M-ZnO allows the majority of visible light of the solar radiation to pass through, which is a critical requirement for its function as a photoanode in DSSCs. Therefore, M-ZnO effectively transmits light to the absorption dye, enabling photoemission and the generation of electrical current [76].

is the conductivity tensor given by equation 10,

is the conductivity tensor given by equation 10,  is the volume of unit cell and

is the volume of unit cell and  is the fermi distribution.

is the fermi distribution.

is the electronic relaxation time designating the time interval between two successive collisions of charge carriers.

is the electronic relaxation time designating the time interval between two successive collisions of charge carriers.  and

and  represent the velocities of charge carries in the corresponding directions

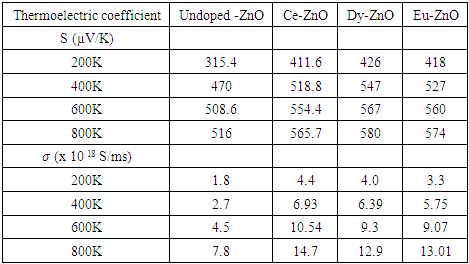

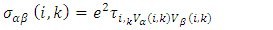

represent the velocities of charge carries in the corresponding directions  respectively. Figure 9(a) shows the computed electrical conductivity in relation to changes in temperature. The figure demonstrates that there is a direct correlation between the electrical conductivity of ZnO and temperature across all compounds that were tested. This is attributed to the enhanced concentration of charge carriers in the conduction band that accompanies a rise in temperature. In terms of conductivity, the Ce doped M-ZnO outperformed all other materials evaluated. Utilizing this high conductivity within DSSC is projected to diminish the electron-hole recombination, consequently enhancing the PCE of the solar cell.The Seebeck coefficient of M- ZnO vary significantly from that of bulk ZnO due to quantum confinement, altered electronic structure, and a reduced dimensionality effect. Its notable from Figure 9(b) that the seebeck coefficient increased with temperature. This can be attributed to enhanced scattering effects and more pronounced energy filtering. The seebeck coefficient observed in this study attained peak values at 516, 565.7, 580 and 574

respectively. Figure 9(a) shows the computed electrical conductivity in relation to changes in temperature. The figure demonstrates that there is a direct correlation between the electrical conductivity of ZnO and temperature across all compounds that were tested. This is attributed to the enhanced concentration of charge carriers in the conduction band that accompanies a rise in temperature. In terms of conductivity, the Ce doped M-ZnO outperformed all other materials evaluated. Utilizing this high conductivity within DSSC is projected to diminish the electron-hole recombination, consequently enhancing the PCE of the solar cell.The Seebeck coefficient of M- ZnO vary significantly from that of bulk ZnO due to quantum confinement, altered electronic structure, and a reduced dimensionality effect. Its notable from Figure 9(b) that the seebeck coefficient increased with temperature. This can be attributed to enhanced scattering effects and more pronounced energy filtering. The seebeck coefficient observed in this study attained peak values at 516, 565.7, 580 and 574  at 800 K for pure M-ZnO and RE (Ce, Dy, Eu) doped M-ZnO respectively as shown in Table 3. Among the materials tested, Dy doped M-ZnO had the highest seebeck coefficient of 580

at 800 K for pure M-ZnO and RE (Ce, Dy, Eu) doped M-ZnO respectively as shown in Table 3. Among the materials tested, Dy doped M-ZnO had the highest seebeck coefficient of 580  at 800K depicting it as the best thermoelectric structure. Based on reports from previous studies, materials with seebeck coefficient above 200

at 800K depicting it as the best thermoelectric structure. Based on reports from previous studies, materials with seebeck coefficient above 200  are considered good thermoelectric compounds [77]. The seebeck coefficient values obtained in this study were higher than 200

are considered good thermoelectric compounds [77]. The seebeck coefficient values obtained in this study were higher than 200  ascertaining pure and RE (Ce, Dy, Eu) doped M-ZnO as viable thermoelectric compound especially at elevated temperatures. RE-doped M-ZnO show modified electrical conductivity and an enhanced Seebeck coefficient. The introduction of RE ions introduce localized states that facilitate charge carrier movement, improving thermoelectric efficiency. RE doping also improve carrier concentration, consequently reducing the resistivity of M-ZnO, particularly in n-type configurations.

ascertaining pure and RE (Ce, Dy, Eu) doped M-ZnO as viable thermoelectric compound especially at elevated temperatures. RE-doped M-ZnO show modified electrical conductivity and an enhanced Seebeck coefficient. The introduction of RE ions introduce localized states that facilitate charge carrier movement, improving thermoelectric efficiency. RE doping also improve carrier concentration, consequently reducing the resistivity of M-ZnO, particularly in n-type configurations.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML

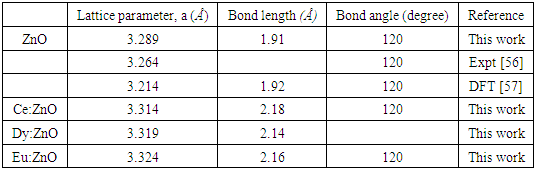

, refractive index (n), absorption critical points and reflectivity at 0 eV (R0)

, refractive index (n), absorption critical points and reflectivity at 0 eV (R0)