-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Nanoscience and Nanotechnology

p-ISSN: 2163-257X e-ISSN: 2163-2588

2012; 2(6): 201-207

doi: 10.5923/j.nn.20120206.08

Pressure Dependent Volume Change in Some Nanomaterials Using an Equation of State

Madan Singh, Spirit Tlali, Himanshu Narayan

Department of Physics and Electronics, National University of Lesotho, Roma 180, Lesotho

Correspondence to: Madan Singh, Department of Physics and Electronics, National University of Lesotho, Roma 180, Lesotho.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

A simple equation of state (EoS) has been derived and used to study the volume expansion of some nanomaterials under the effect of pressure. Only two input parameters, namely, the bulk modulus and its first pressure derivative are required for calculations. We have considered a wide variety of nanomaterials, such as, metals [Ni (20 nm), α-Fe (nanotubes), Cu (80nm) and Ag (55nm)], semiconductors [Ge (49 nm), Si, CdSe (rock-salt phase), MgO (20nm) and ZnO], and carbon nanotube (CNT) to analyze the effects of pressure on them. The results have been compared with the available experimental data as well as with those obtained through other theoretical approaches. Excellent agreement between theoretical and experimental data, throughout the range of pressure under investigation, supports the validity of present approach.

Keywords: High pressure, Equation of State, Nanomaterials

Cite this paper: Madan Singh, Spirit Tlali, Himanshu Narayan, "Pressure Dependent Volume Change in Some Nanomaterials Using an Equation of State", Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 201-207. doi: 10.5923/j.nn.20120206.08.

1. Introduction

- Over the past decade nanomaterials have been the subject of immense interest. These materials, remarkable for their extremely small size, have the potential for wide ranging industrial, biomedical, and electronic applications. Therefore, it is not just a matter of great interest, but also a necessity, to study the thermodynamic properties of nanocrystalline (NC) materials. Investigation of the behaviour of NC materials under high pressure can provide valuable information about their intrinsic microstructural characteristics. Nanomaterials differ significantly from their bulk counterparts primarily because of their small size. The study of NC materials with particle dimensions less than 100 nm is an active area of research in physics, chemistry and engineering[1]. Nanomaterials are usually very sensitive to external parameters, such as, temperature and pressure. Many physical properties of these materials strongly depend on their structures and interatomic distances. These distances may be varied by the application of sufficient pressure, and the surface effects, which are virtually unimportant in the case of bulk materials, but become extremely significant in nanomaterials because of their large surface to volume ratio. The atomic structure of materials, their stability and atomic interactions are related in complex ways to their thermodynamic properties. Therefore, investigation of the thermodynamic properties of NC materials constitutes one of the most interesting areas in nano-research. It is of fundamental interest to explore the thermodynamic consequences of a material system with interfacial regions. Various physical properties such as hardness, melting temperature, sintering ability and electronic structure may be dependent upon particle size. Nanomaterials, nanoparticles, nanowires and nanotubes have been reported to showphysical, chemical and mechanical properties that are markedly different from their corresponding bulk counterparts[2-8]. For example, phonon frequency blue shift innano-semiconductors and nanometals, increase of elastic modulus in thin films and nanoparticles[9-10], decrease of melting temperature and thermal conductivity in nanocrystals[11-12] are associated with the particle size of the material under consideration. In many applications, the understanding of material properties that are influenced by pressure becomes crucial. Therefore, investigation of the behaviour of nano-sized materials under high pressure is indispensable, especially due to the immense potential of applications associated with these materials. Fullerenes or hollow carbon nanospheres were discovered in the year 1985[13], and have since been a topic of substantial research interest. The high pressure behaviour of carbon nanotubes (CNT) has been investigated up to 19 GPa with the help of synchrotron based angle dispersive X-ray diffraction[14]. The CNT do not show any structural transformation even up to very high pressure. Nanocrystalline nickel has been a subject of considerable experimental and theoretical work in the recent years[15-17]. The magnetic[18-19], mechanical and electrical behaviour [20], diffusion coefficient and vibarational model[21] of NC Ni have been widely investigated. At the same time, the behaviour of thermo-elastic constants under the effects of pressure and temperature has attracted the attention of theoretical as well as experimental workers[22-24] because of their essential need in the study of various technological problems. Structural transformations in CdSe nanocrystals has been studied using high pressure X-ray diffraction and high pressure optical absorption at room temperature[25]. The nanocrystals undergo from wurtzite to rocksalt phase transition analogous to that observed in bulk CdSe. The phase transition pressure in NC CdSe varies from 3.6 to 4.9 GPa for crystallites ranging from 21 to 10 Å in radius in comparison to the value of 2 GPa for the bulk material. Effect of particle size on the compressibility of MgO with particle size around 100 nm has been studied by Rekhi et. al.[26] through X-ray diffraction studies. Nanocrystalline iron has been the subject of many experimental and theoretical studies. High pressure X-ray diffraction studies have been carried out[27] up to a 20 GPa on α-Fe filled nanotube. Size dependent elastic modulus and vibration frequency of Cu, Ag and Si nanoparticles have been reviewed based on their inherent lattice strain and binding energy change and the intrinsic correlation between the elasticity and vibration properties has been discussed[28].Therefore, it is very much evident that numerous experimental studies have been performed to understand the high pressure performance of nanomaterials. However, the theoretical efforts are scarce. Even though some theoretical investigations based on inter-ionic potential models[29-30] have been carried out by some workers, there have been some weaknesses in the adopted models. For example, these models not only involve various approximations, but require heavy computational work also, to get to the final results. On the other hand, the study based on equation of state (EoS) at high pressure and high temperature, is of fundamental interest because this approach permits interpolation and extrapolation into the regions where experimental data are not readily available. In this article, we present a simple theoretical approach to study the compression behaviour of nanosystems under pressure. An EoS has been developed and after examining its validity, it has been used to calculate the change in volume of some nanomaterials under high pressure. Moreover, the results calculated from our EoS have been compared with those obtained through other methods.

2. Method of Analysis

- The dependence of volume on pressure can be written as[31],

| , (1) |

is the relative change in volume, and

is the relative change in volume, and  ,

,  and

and  are size dependent parameters, which may be determined from the definition of bulk modulus, and its first and second order pressure derivatives, respectively. In Eq. (1), the higher order terms beyond the second term may be ignored because of their smaller contributions. This is advantageous also because higher order pressure derivatives of bulk modulus, which are not available for nanomaterials, are involved in these higher terms.The Bulk modulus is defined as,Using this definition of bulk modulus, Eq. (1) may be written as,

are size dependent parameters, which may be determined from the definition of bulk modulus, and its first and second order pressure derivatives, respectively. In Eq. (1), the higher order terms beyond the second term may be ignored because of their smaller contributions. This is advantageous also because higher order pressure derivatives of bulk modulus, which are not available for nanomaterials, are involved in these higher terms.The Bulk modulus is defined as,Using this definition of bulk modulus, Eq. (1) may be written as, | (2) |

.Using all the above equations and applying the boundary condition,

.Using all the above equations and applying the boundary condition,  , when

, when  , we obtain,

, we obtain,  and

and  .Substituting these values of

.Substituting these values of  and

and  in Eq. (1), we get the EoS as,

in Eq. (1), we get the EoS as, | (3) |

,where,

,where,  is the thermal pressure and

is the thermal pressure and  , the lattice potential energy. This Eq. gives the relation for thermal expansion as[33],

, the lattice potential energy. This Eq. gives the relation for thermal expansion as[33], | (4) |

, Eq. (4) may be rewritten as,

, Eq. (4) may be rewritten as, | (5) |

), Eq. (5) gets modified as,

), Eq. (5) gets modified as, ,which, upon rearrangement yields,

,which, upon rearrangement yields, | (6) |

is independent of

is independent of  , Murnaghan EoS may be written as[35],

, Murnaghan EoS may be written as[35], | (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

is defined as

is defined as  , and using the approximation

, and using the approximation  the parameter

the parameter  becomes

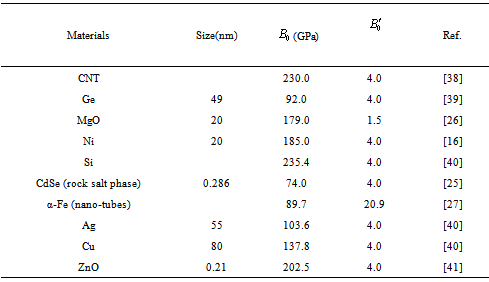

becomes  .All these equations of state need only two input parameters, i.e., the bulk modulus and its first order pressure derivative, which are compiled in Table 1 for the nanomaterials considered in this work. Another important point to note is that the EoS developed here is independent of the crystal structure of the material under investigation. Therefore, it can expectedly be applied to study the pressure dependent volume expansion of a wide variety of materials.

.All these equations of state need only two input parameters, i.e., the bulk modulus and its first order pressure derivative, which are compiled in Table 1 for the nanomaterials considered in this work. Another important point to note is that the EoS developed here is independent of the crystal structure of the material under investigation. Therefore, it can expectedly be applied to study the pressure dependent volume expansion of a wide variety of materials.

|

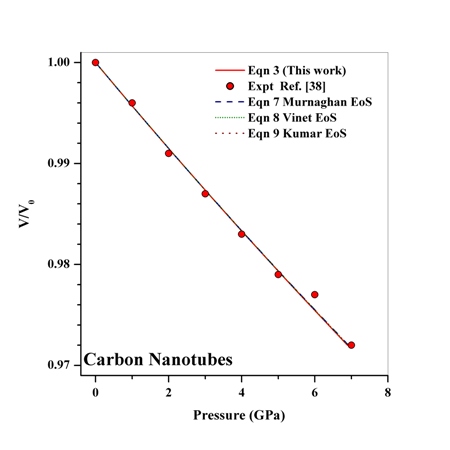

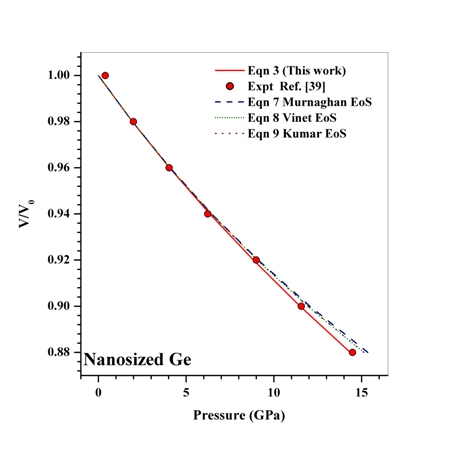

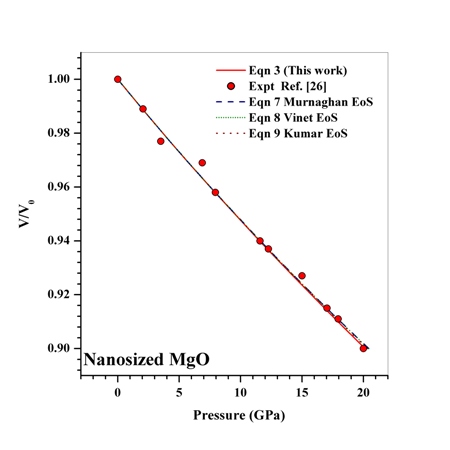

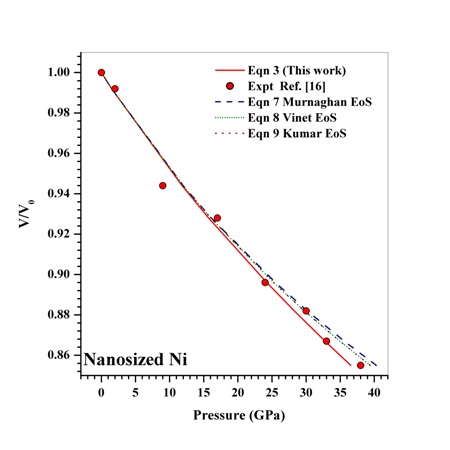

3. Results and Discussion

- The value of volume expansion (

) have been calculated as a function of pressure, using Eqs. (3), (7), (8) and (9), respectively, for CNT, Ge (49 nm), MgO (20 nm), Ni (20 nm), Si, CdSe (rock salt phase), α-Fe (nano-tubes), Ag (55 nm), Cu (80 nm) and ZnO nanomaterials. These materials were chosen for the analysis primarily because of the availability of input parameters (as given in Table 1) required for calculations. Additionally, experimental data are also available for the first seven materials. Nevertheless, the selection of these nanomaterials has made our analysis more versatile, because a wide variety of materials, from semiconductors to pure metals, have been included.Before starting the discussion on results, we define a percent matching parameter,

) have been calculated as a function of pressure, using Eqs. (3), (7), (8) and (9), respectively, for CNT, Ge (49 nm), MgO (20 nm), Ni (20 nm), Si, CdSe (rock salt phase), α-Fe (nano-tubes), Ag (55 nm), Cu (80 nm) and ZnO nanomaterials. These materials were chosen for the analysis primarily because of the availability of input parameters (as given in Table 1) required for calculations. Additionally, experimental data are also available for the first seven materials. Nevertheless, the selection of these nanomaterials has made our analysis more versatile, because a wide variety of materials, from semiconductors to pure metals, have been included.Before starting the discussion on results, we define a percent matching parameter,  in order to facilitate a quantitative comparison and presentation of results, as follows:

in order to facilitate a quantitative comparison and presentation of results, as follows: | (10) |

etc. are the relative differences or deviations between two

etc. are the relative differences or deviations between two  data at a given

data at a given  value, and

value, and  is the total number of such data-points available for comparison. Based on this definition obviously the value of

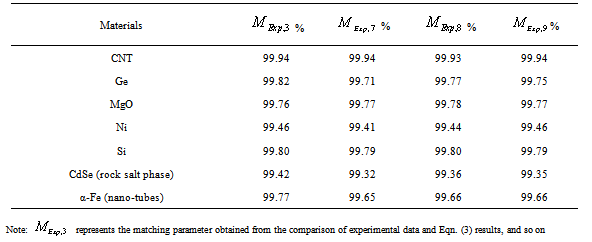

is the total number of such data-points available for comparison. Based on this definition obviously the value of  for the best matching would be 100%. It should also be understood that all equations of state discussed in this work have matched with the experimental data better than 99% in terms of

for the best matching would be 100%. It should also be understood that all equations of state discussed in this work have matched with the experimental data better than 99% in terms of  , as calculated from Eqn. (10), which was quite expected. Therefore, in a given comparison, any significant deviation in terms of the

, as calculated from Eqn. (10), which was quite expected. Therefore, in a given comparison, any significant deviation in terms of the  value has emerged only as digits after the decimal point.The results of our analysis are presented in Figs. 1-10 along with the experimental data (where available) for comparison. We have also included in the graphs, the data calculated using Murnaghan[35], Vinet[36] and Kumar[37] EoS. In general, small deviations with respect to the experimental values are obvious for all nanomaterials, especially at high pressures, when

value has emerged only as digits after the decimal point.The results of our analysis are presented in Figs. 1-10 along with the experimental data (where available) for comparison. We have also included in the graphs, the data calculated using Murnaghan[35], Vinet[36] and Kumar[37] EoS. In general, small deviations with respect to the experimental values are obvious for all nanomaterials, especially at high pressures, when  was calculated using other theoretical approaches (Murnaghan, Vinet and Kumar EoS). The overall percentage matching parameter

was calculated using other theoretical approaches (Murnaghan, Vinet and Kumar EoS). The overall percentage matching parameter  for each data set with respect to the available experimental data, corresponding to each nanomaterials, has been calculated and shown in Table 2. In almost all cases the value for

for each data set with respect to the available experimental data, corresponding to each nanomaterials, has been calculated and shown in Table 2. In almost all cases the value for  calculated in comparison of Eqn. (3) data with experiments is better than that obtained considering the latter alongside other theoretical approaches. This observation confirms the improvement achieved with the current theory. It is noteworthy to mention here that we have considered only up to the second term of the series in Eqn. 1, because inclusion of higher terms requires second and higher order pressure derivatives of the bulk modulus, which are still not available for most of the nanomaterials.Excellent agreement between the theoretical values of

calculated in comparison of Eqn. (3) data with experiments is better than that obtained considering the latter alongside other theoretical approaches. This observation confirms the improvement achieved with the current theory. It is noteworthy to mention here that we have considered only up to the second term of the series in Eqn. 1, because inclusion of higher terms requires second and higher order pressure derivatives of the bulk modulus, which are still not available for most of the nanomaterials.Excellent agreement between the theoretical values of  as a function of

as a function of  , obtained from Eqn. (3) has been found with the corresponding experimental data for CNT[38], Ge[39], MgO[26] and Ni[16] nanomaterials, which is very much evident in Figs. 1-4. Interestingly, the theoretical data obtained from Eqns. (7), (8) and (9) are throughout in good agreement with the experimental values only for CNT and MgO nanomaterials; whereas, for Ge and Ni, slightly higher values of

, obtained from Eqn. (3) has been found with the corresponding experimental data for CNT[38], Ge[39], MgO[26] and Ni[16] nanomaterials, which is very much evident in Figs. 1-4. Interestingly, the theoretical data obtained from Eqns. (7), (8) and (9) are throughout in good agreement with the experimental values only for CNT and MgO nanomaterials; whereas, for Ge and Ni, slightly higher values of  , especially in the higher

, especially in the higher  regime, have been produced. In terms of the

regime, have been produced. In terms of the  values, close to 99.94% match has been obtained between the experimental data and all the equations of state mentioned in this work, for CNT. However, for Ge, Eqn. (3) has matched

values, close to 99.94% match has been obtained between the experimental data and all the equations of state mentioned in this work, for CNT. However, for Ge, Eqn. (3) has matched  = 99.82% with the experiments as against 99.71, 99.77 and 99.75% match obtained with Eqns. (7), (8) and (9), respectively. Best match (

= 99.82% with the experiments as against 99.71, 99.77 and 99.75% match obtained with Eqns. (7), (8) and (9), respectively. Best match ( value 99.46%) was also found between experimental data and Eqn. (3) results, for nanosized Ni. However, for MgO, Eqn. (8) showed the best matching with

value 99.46%) was also found between experimental data and Eqn. (3) results, for nanosized Ni. However, for MgO, Eqn. (8) showed the best matching with  = 99.78% that was only marginally better than the

= 99.78% that was only marginally better than the  = 99.76% obtained using Eqn. (3). We would also like to mention that in the high-pressure regime (

= 99.76% obtained using Eqn. (3). We would also like to mention that in the high-pressure regime ( calculated only for the last few points with highest values of pressure), best matching has been observed only between the experimental data and Eqn. (3) results. These observations clearly consolidate the validity of the EoS given in Eqn. (3), especially at higher values of

calculated only for the last few points with highest values of pressure), best matching has been observed only between the experimental data and Eqn. (3) results. These observations clearly consolidate the validity of the EoS given in Eqn. (3), especially at higher values of  in comparison with the other equations of state given in Eqns. (7), (8) and (9).Reasonably good agreement has been found between experimental values of

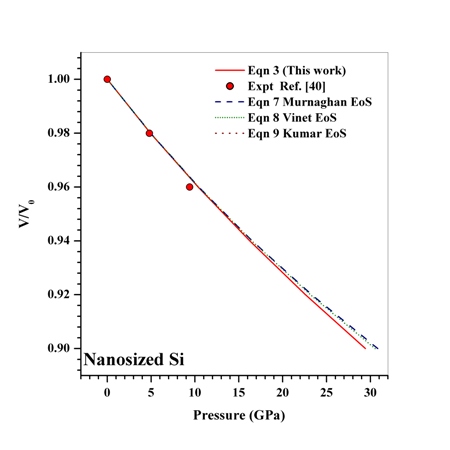

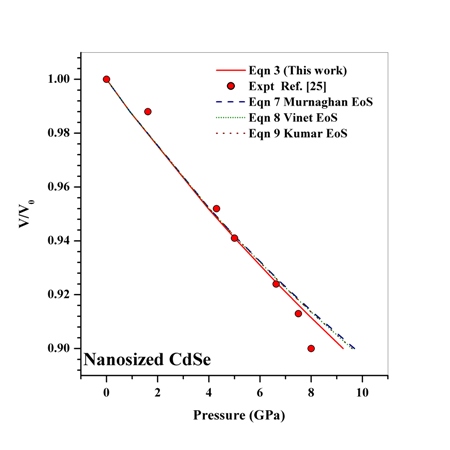

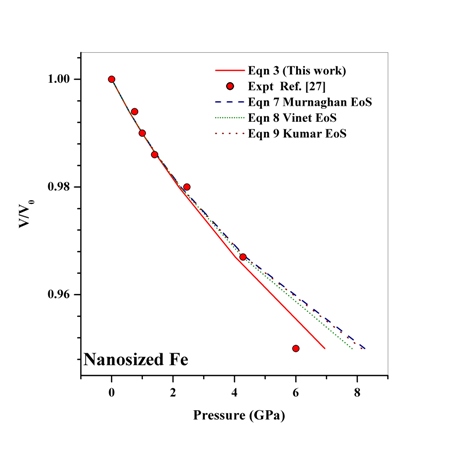

in comparison with the other equations of state given in Eqns. (7), (8) and (9).Reasonably good agreement has been found between experimental values of  for Si[40], CdSe[25] and Fe[27], with the respective theoretical estimations obtained using Eqn. (3), which can be clearly seen in Figures. 5-7. For these materials also, the other theoretical data[obtained from Eqns. (7), (8) and (9)] apparently show better agreement in the low pressure regime only, whereas Eq. (3) fits throughout the range of pressure investigated. It should be noted that experimental data for Si are available only up to

for Si[40], CdSe[25] and Fe[27], with the respective theoretical estimations obtained using Eqn. (3), which can be clearly seen in Figures. 5-7. For these materials also, the other theoretical data[obtained from Eqns. (7), (8) and (9)] apparently show better agreement in the low pressure regime only, whereas Eq. (3) fits throughout the range of pressure investigated. It should be noted that experimental data for Si are available only up to  GPa, where all theoretical curves matched nicely with the experimental points. However, at higher pressure (

GPa, where all theoretical curves matched nicely with the experimental points. However, at higher pressure ( GPa), the values of volume expansion generated by Eqns. (7) and (8) deviated from Eqn. (3) results as the latter apparently followed the extrapolation of experimental points. Once again the best matching between experiment and theory was found when Eqn. (3) was used. In terms of the matching parameter

GPa), the values of volume expansion generated by Eqns. (7) and (8) deviated from Eqn. (3) results as the latter apparently followed the extrapolation of experimental points. Once again the best matching between experiment and theory was found when Eqn. (3) was used. In terms of the matching parameter  defined in Eqn. (10), the agreement was even better when only a few points at higher pressure were considered.It may be concluded from the above discussion that the EoS obtained in this work[Eqn. (3)], in general, can produce much better pressure dependent volume expansion data, as compared to other equations of state[Eqns. (7), (8) and (9)] for a wide range of nanomaterials. With this observation, we may now use Eqn. (3) to predict the nature of volume expansion under pressure for some other nanomaterials, for which the experimental data are currently not available.

defined in Eqn. (10), the agreement was even better when only a few points at higher pressure were considered.It may be concluded from the above discussion that the EoS obtained in this work[Eqn. (3)], in general, can produce much better pressure dependent volume expansion data, as compared to other equations of state[Eqns. (7), (8) and (9)] for a wide range of nanomaterials. With this observation, we may now use Eqn. (3) to predict the nature of volume expansion under pressure for some other nanomaterials, for which the experimental data are currently not available.  | Figure 1. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for carbon nanotubes for carbon nanotubes |

| Figure 2. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for nanosized Ge for nanosized Ge |

| Figure 3. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for nanosized MgO for nanosized MgO |

| Figure 4. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for nanosized Ni for nanosized Ni |

| Figure 5. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for nanosized Si for nanosized Si |

| Figure 6. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for nanosized CdSe for nanosized CdSe |

| Figure 7. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for Fe nano-tubes for Fe nano-tubes |

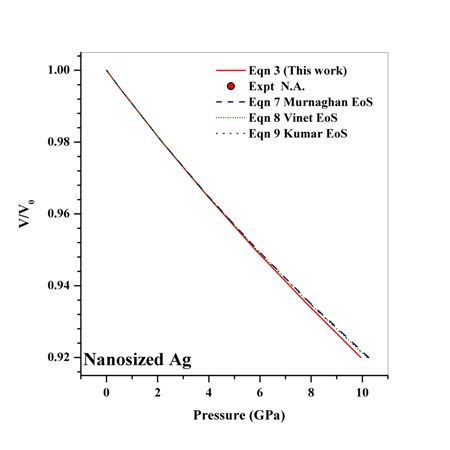

| Figure 8. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for nanosized Ag for nanosized Ag |

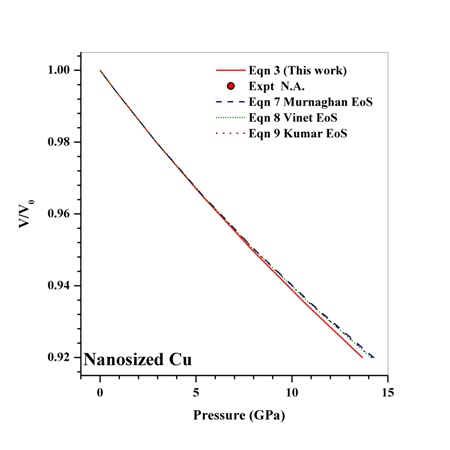

| Figure 9. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for nanosized Cu for nanosized Cu |

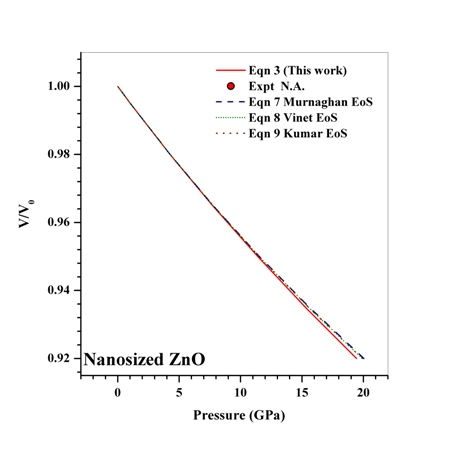

| Figure 10. Volume expansion ( ) as a function of pressure ) as a function of pressure  for nanosized ZnO for nanosized ZnO |

|

under pressure for Ag, Cu and ZnO nanoparticles. Since the experimental data for these materials are not available, we compare our results with those obtained from other equations of state[Eqns. (7), (8)and (9)]. In terms of

under pressure for Ag, Cu and ZnO nanoparticles. Since the experimental data for these materials are not available, we compare our results with those obtained from other equations of state[Eqns. (7), (8)and (9)]. In terms of  , close to or better than 99.90% overall matching was found between all theoretical results. Expectedly, some small deviations can be observed at higher pressure, even though there is excellent match in the

, close to or better than 99.90% overall matching was found between all theoretical results. Expectedly, some small deviations can be observed at higher pressure, even though there is excellent match in the  GPa region for Ag and Cu, and

GPa region for Ag and Cu, and  GPa for ZnO nanoparticles. Combining with the observations mentioned above, we can predict that the experimental values, whenever available, should agree with the data calculated from Eqn. (3) more closely than they do with other theoretical estimations discussed in this work.

GPa for ZnO nanoparticles. Combining with the observations mentioned above, we can predict that the experimental values, whenever available, should agree with the data calculated from Eqn. (3) more closely than they do with other theoretical estimations discussed in this work.4. Conclusions

- In this work, we have presented a straightforward theory to study the behaviour of volume expansion as a function of pressure for some nanomaterials. The EoS presented here is simple in the sense that it requires only two input parameters, namely, the bulk modulus and its first order pressure derivative. Validity of our approach has been supported by the fact that our EoS can be derived also through the theory of Mie-Gruneisen EoS. It is also relevant to remark that our EoS has been developed in such a way that it is independent of the crystal structure of the material under consideration.Using our EoS, we have theoretically calculated the volume expansion with increasing pressure, for various nanomaterials and compared the results with available experimental data. It has been observed that for carbon nanotube, Ge, MgO and Ni nanomaterials, our theory produces the best match with experimental data. For nano-sized Si, CdSe and α-Fe nano-tubes also, excellent agreement between the experiments and our theoretical estimations has been observed. In order to consolidate the validity of our approach, we have also compared our theoretical results with those obtain from some other equations of state, such as, Murnaghan’s, Vinet’s and Kumar’s. Very significant agreement has been observed in the low pressure values. However, in the high pressure regime, our theory has produced better matching with the experimental data in comparison with the other methods. The most interesting observation in this work is that our theory agrees with the experiments throughout the pressure range investigated for a given nanomaterial, whereas the other theories tend to deviate, in general, towards higher

values, especially at high pressure. Finally, we have applied our EoS to predict the nature of pressure dependent volume expansion for some nanomaterials, such as Ag, Cu and ZnO, for which experimental data are currently not available. When compared with the other theoretical data, our results look acceptable as well as closer to the expected experimental values.These results may be of some interest to the scholars involved in the experimental work. On the basis of overall discussion, it may be emphasized that our EoS explains well the volume expansion of nanomaterials considered in this article.

values, especially at high pressure. Finally, we have applied our EoS to predict the nature of pressure dependent volume expansion for some nanomaterials, such as Ag, Cu and ZnO, for which experimental data are currently not available. When compared with the other theoretical data, our results look acceptable as well as closer to the expected experimental values.These results may be of some interest to the scholars involved in the experimental work. On the basis of overall discussion, it may be emphasized that our EoS explains well the volume expansion of nanomaterials considered in this article.  Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML