-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Neuroscience

2012; 1(1): 1-7

doi: 10.5923/j.neuroscience.20120101.01

Prevalence of Depression and Cognitive Distortion among a Cohort of Malaysian Tertiary Students

Kai-Yein Teo, Yee-How Say

Department of Biomedical Science, Faculty of Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) Perak Campus, Kampar, Perak, 31900, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Yee-How Say, Department of Biomedical Science, Faculty of Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) Perak Campus, Kampar, Perak, 31900, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of depression, cognitive distortion and their associated factors among a cohort of 400 Malaysia tertiary students, recruited from 40 colleges and universities located at East and West Malaysia. Participants were assessed using Becks Depression Inventory (BDI)-IA, Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ) and several self-designed questions. The prevalence of depression among tertiary students in Malaysia was 21.3%, with mean BDI and ATQ scores significantly lower (p<0.05) among males (9.6±8.6 and 55.0±19.0, respectively), compared to females (11.6±9.7 and 60.7±23.6, respectively). BDI scores were significantly different among fields of study (p=0.022), but not levels of study (p=0.154). Severity of depression had a strong correlation (r=0.821) with the level of cognitive distortion. Substance use was more prevalent among males during depression while suicidal thoughts were more prevalent among those tested to be depressed. Females and those found to be depressed were more prone to skip meal during depression. Understanding the relation between depression, cognitive distortion and its associated factors would benefit intervention effort among tertiary students, which is known to be a prone age group.

Keywords: Depression, Cognitive distortion, Becks Depression Inventory, Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire, Malaysia

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Among all mental disorders, depression is the most common[1]. Depressive disorder is also called unipolar depressive disorder as the mood disturbance extends to only one direction, which is feeling down. Depressive disorders can be categorized into a few subtypes, which include major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, postpartum disorder and seasonal affective disorder[1]. Depressive disorders can be diagnosed using standard symptomatic criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV)[2] or the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10)[3]. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most severe and the most common form of depression among all subtypes and it involves patients’ changes in emotional state, motivation, functioning, motor behavior and cognition[4]. Epidemiological studies of depression found that risk factors of depression vary predominantly according to gender and age[4]. Depression generally begins early in life (mid to late 20s) and is two times more prevalent among women than men[4,5]. Besides, studies have also reported emerging adults aged 18 to 25 years as those who have the highest prevalence of suffering from depression among anyage group[6].The course of depression also includes cognitive symptoms characterized by biased way of thinking such as the thoughts of being worthless, guilty and suicide ideation[7]. This erroneous thinking is described as “cognitive distortion” - defined as an illogical and maladaptive response to early negative life events that leads to the feeling of incompetence and unworthiness which are reactive whenever a new situation resembling the original events arise[8]. This distorted thinking often came to one’s mind automatically, causing one to accept it as a fact rather than an opinion[4], and is depicted as the tendency of looking at the glass as being half empty instead of being half full[4]. Numerous studies have found increased cognitive distortion among depressed individuals compared to non-depressed[4].Depression is also often linked with problematic behaviors such as substance use (smoking, drinking and illicit drug use)[9,10], dysregulated eating (skipping meals and eating more than usual)[11] and suicidal thoughts[12]. Co-existence of such behaviors with depression may subsequently lead to further health complication or even co-morbidities. Even though these ways of coping stress are commonly associated with depression, its trend is dissimilar to the trend of depression. For example, men generally drink more than women, yet association of depression and alcohol disorders were higher among women than in men[13]. Thus, more effort is needed to interpret trend of depression-related problematic behaviors among those depressed.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participant Recruitment and Characteristics

- The survey was carried out via both questionnaire distribution and web survey. Targeted participants were Malaysian students of any college and university in Malaysia. The survey period was from 22 December 2010 to 19 January 2011. In both the written questionnaire and web survey, participants were informed that the survey was concurrently being conducted in both ways to avoid duplicates. Participants were invited to participate in the web survey via the e-mail-invitation application of the Kwik Surveys (www.kwiksurveys.com), a free online survey application. The web survey was set to only allow participants to participate once and duplicated responses were blocked using internet protocol (IP) address identification. Personal information that was required to be given by the participants were gender, age, course of study, current level of study and name of institute. Of the 682 surveys distributed via printed copies and e-mail invitations, the response rate was 70%, and the percentage of fully completed questionnaire was 83.8%. Therefore, a final total of 400 students from 40 colleges and universities located at East and West Malaysia participated in this survey. Participants consisted of 198 (49.5%) females and 202 (50.5%) males, ranging from 18 to 25 years (mean±SD = 21.2±1.4 years). The institutional board approved this study, all individuals participating in this study signed informed consents, and the study was conducted in accordance with the 1995 Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Edinburgh 2000).

2.2. Beck Depression Inventory-IA (BDI-IA)

- In the current study, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)-IA, the revised version of BDI[17] was used, with the English sentence structure of items simplified to facilitate participants’ understanding. For Items 1, 5, 11 and 15, English terms that were less commonly used in the Malaysian society were replaced by simpler terms with similar meanings. For item 1C, instead of “I can't snap out of it,” “I can't get out of it” was used. For items 5B and 11C, instead of “good part of the time,” “often” was used. For item 19, conversion units of kilograms for pounds were provided as pound is less likely used as a weighing unit in Malaysia. Item 9 of BDI was extracted as an individual question to assess suicidal ideation among students. Participants that chose (A) of item 9 were regarded as not having any suicidal ideation, while (B), (C), or (D) were regarded as having suicidal ideation.

2.3. Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ)

- The Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ) is a 30 items instrument developed by Hollon and Kendall (1980)[18] to identify and measure the frequency of automatic negative thoughts about self that are associated with depression. Hollon and Kendall (1980)[18] also claimed ATQ to have good concurrent validity, correlating with measures of depression from the Beck Depression Inventory. This instrument was given unchanged and was delivered in English to the participants.

2.4. Self-designed Questions

- Several questions were designed to assess factors and problematic behaviors related to depression. Aspects covered in these questions were selected based on reviews on similar studies done in Malaysia and overseas[19,20]. The questions included “Are you depressed and does it affect your studies?” “To whom are you most likely to approach when/if you are depressed,” “Which of the following matters is most likely or has caused you to be depressed?” and the likelihood for substance abuse (alcohol drinking, taking illegal drugs, smoking, eating more than usual and skipping meal) when/if faced with depression.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17.0. Cronbach’s alpha was tested on both BDI and ATQ to determine the internal consistency and reliability of each test. Two-tailed independent sample T-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were carried out to determine the significance of the prevalence rate. Scatter plot of BDI score versus ATQ score was plotted and the correlation of both scores was determined by Pearson’s correlation test. Problematic behaviors of depression were cross tabulated with gender and depression status and the significance was tested using Chi-square test. P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Correlating Depression, Cognitive Distortion, Gender, Level and Field of Study

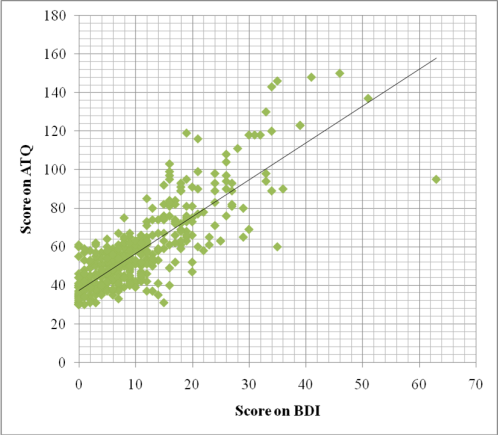

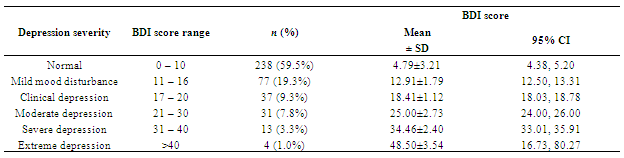

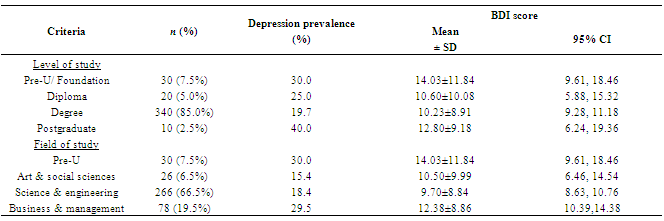

- Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient tested on both BDI (α=0.905) and ATQ (α=0.962) showed high internal coefficiency and reliability. The alpha coefficient obtained for ATQ was similar to the value reported by other studies[18,21,22]. This shows that the minor amendments done did not affect the reliability of the instruments. The frequency of each category of depression severity is presented in Table 1. The prevalence of depression among tertiary students in Malaysia was 85/400 or 21.3%. Remaining students were normal (59.5%) or only suffered from mild mood disturbance (19.2%). Descriptive statistics of BDI score for each category of depression severity revealed variation in the mean score acquired by participants in each category. One way ANOVA was carried out and the mean score of BDI for each category of depression severity was tested to be significantly different, F(5, 394) = 737.95, p< 0.001.Descriptive statistics of scores on BDI and ATQ for both genders showed that mean BDI and ATQ scores were significantly lower (p<0.05) among males (9.6±8.6 and 55.0±19.0, respectively), compared to females (11.6±9.7 and 60.7±23.6, respectively). The depression prevalence rate was also higher in females (26.3%) compared to males (16.3%). Scatter plot of BDI score versus ATQ score and Pearson’s correlation test revealed strong positive correlation between BDI score and ATQ score among the participants (Figure 1).Descriptive statistics of BDI score for each category of study level and study field of participants (Table 2) revealed variation in the mean score acquired by participants in each category. One way ANOVA tested on BDI scores showed no significant difference among levels of study[F(3, 396) = 1.760, p=0.154], but were significantly different among fields of study[F(3, 396) = 3.251, p=0.022].

3.2. To whom Tertiary Students Approach, Factors Claimed to Cause Depression and Problematic Behaviors Associated with Depression

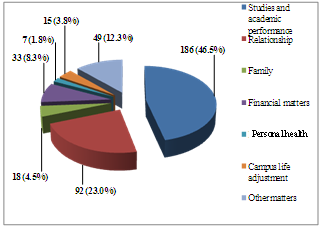

- Among participants that were tested to be depressed and also self-claimed to be depressed, 54/85 or 63.5% of them complained that depression did affect their studies. Almost half of the students (46.5%) claimed studies and academic performance as the main factors that will most likely or have caused them to be depressed, followed by relationship matters, other matters, financial matters, family matters, campus life adjustment and finally, personal health (Figure 2). This indicates that academic performance was both the main cause and consequence of depression among Malaysian tertiary students.

|

|

|

| Figure 2. Factors that participants claim were most likely to cause depression |

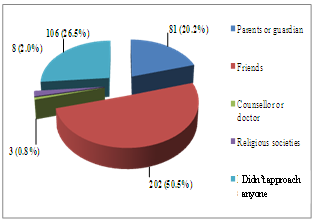

| Figure 3. To whom the participants were most likely to approach when or if depressed |

4. Discussion

- The prevalence of depression among tertiary students in Malaysia was 21.3%, similar to the Hong Kong rate[23]. However, the current prevalence rate was much higher when compared to similar studies among college students in China[24] and in USA[25,26]. Interestingly, the prevalence rate of present study was actually half of the prevalence reported among Malaysian medical students[16], which could be explained by the fact that the medical degree is more challenging compared to any other undergraduate courses[27]. Furthermore, the present study reported significant difference in prevalence of depression among students of different fields of study. Similarly, a study done among Turkish university students[28] revealed significant difference in prevalence of depression among students majoring in social science and political science, basic science and engineering and medicine.There was a strong positive correlation between the severity of depression and the level of cognitive distortion. Findings that showed increased cognitive distortion with severity of depression was also reported in research among juvenile delinquents in Malaysia[19] and among a group of students in USA[29]. The prevalence of depression reported in this study was significantly higher among females and in parallel, females also showed elevated severity in cognitive distortion as compared to males. The etiology of this trend has yet to be elucidated, but it is said to be caused by the involvement of precursor and metabolites of female gonadal hormones in the regulation and functioning neurotransmitter and neuronal circuits have been implicated for the occurrence of depression[30].In times of depression, majority of the students preferred to approach their friends, similar to the finding among Malaysian college and university students[16,20]. There were 26.5% of them who did not approach anyone when depressed. In Canada, only 7% of those diagnosed with depression sought treatment; in USA 10.9%; in Netherlands 13.4% (reviewed in[31]). The refusal of these individuals to obtain any assistance when depressed may be due to their belief in their own capability to overcome depression by themselves. It was also depicted that approaching parents or guardian was the third popular choice while approaching counselors or doctors at time of depression was the least popular choice among students. The results obtained in this research differed than the one reported among Malaysian college and university students[20], where 9.3% of students were willing to seek professional mental help and 12.4% would approach their parents instead. Studies and academic performance were regarded as the main sources of depression among students. This observation may be due to stress in the academic environment such as examination and demand for better academic performance. Vice versa, students that were tested to be depressed also claimed depression to affect their studies. Similarly, research by Rodriguez et al. (2005)[32] also reported lower grades at baseline among adolescent with severe depressive symptoms compared to those with milder depressive symptoms. Significant association was found between tendency to smoke and alcohol drinking with gender, but not depression status, with males more likely to indulge in the habits. These findings agreed with previous studies[33,34] which showed that association of smoking and major depression vary according to gender. However, unlike the finding that reported stronger association among females[34], the current study observed stronger association among males instead. This may be explained by the Malaysian culture which sees smoking as a disgraceful behavior among women[35], thus causing more male smokers than females. Thus these findings implicate that among tertiary students in Malaysia, gender is a predictor for smoking and drinking behavior in depressive situation, rather than depression status. The number of positive responders in association of illicit drug use during depression was exceptionally low. However, it should be noted that this could be due to under-reporting in order to protect oneself from being caught and penalized by the strict drug law enforcement in Malaysia.The current finding which showed that behavior of eating more than usual was not significant in terms of different gender and depression status conflicted with findings of several studies conducted among Caucasians[36-38]. Disparate observation obtained in current study may point out different symptoms of depression and coping techniques between Asians and Caucasians. Those tested to be depressed were more likely to develop suicidal thought compared to those that were not depressed. Although only few of those that have suicide ideation will end up commit suicide[39], youth is still the major contributor to the suicidal rate in Malaysia[40] and therefore necessitates further investigation.As majority of the theories and references cited in this study were developed in Western countries, discrepancy in findings is expected. These dissimilarities most probably arose due to difference in culture, social norms and living style between populations of different countries. It should be noted that the discrepancy in findings may also be due to convenient sampling of participants in current study, variation in sample size and inventories used in the diagnosis of depression. The number of subjects recruited in the study is rather small, limiting the power for statistical analysis of the results and also cannot be generalised to the entire population of college/university students in Malaysia. Future studies are encouraged to minimize the use of self reported inventories and to carry out longitudinal studies to better understand the inter-relationship of depression and its associated factors.

5. Conclusions

- In conclusion, this study has provided a better picture of the mental health among tertiary students in Malaysia. The high depression prevalence and depression-related problematic behavior that arise in response to depression indicate poor coping skills among these students. Thus, this matter warrants proper attention from the Malaysian Ministry of Health to provide better mental health care among tertiary students in Malaysia. More effort should be incorporated to solve the underlying factors that predispose students to depression rather than the symptoms of depression itself.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This project was funded by the Department of Biomedical Science, University Tunku Abdul Rahman. We also gratefully acknowledge all the volunteers who have participated in this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML