-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2021; 11(2): 27-37

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20211102.01

Received: Jul. 22, 2021; Accepted: Sep. 13, 2021; Published: Oct. 15, 2021

Boosting Diaspora Remittances as a Key Source of Investment Capital: The Case of Zimbabwe

Rangarirai Muzapu, Taona Havadi

University of International Business and Economics [UIBE], Business School (Administration), Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence to: Rangarirai Muzapu, University of International Business and Economics [UIBE], Business School (Administration), Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Zimbabwe has generally been witnessing a significant decline of meaningful Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows for some reason. The decline of FDI inflows has seen most developing countries, seeking other alternatives to attract foreign currency into their respective economies. In particular, the diaspora community has been receiving increasing attention from respective governments across the globe. Indeed, diaspora remittances have been increasing in recent times, proving to be a significant alternative source of foreign investment capital. It is, however, the contention of this paper that, in the case of Zimbabwe, diaspora remittances are not being fully exploited in terms of this resource's immense potential, as an alternative source of investment capital. In this regard, this paper sought to proffer ideas and/or suggestions on the steps that could be adopted by the Government of Zimbabwe to unlock the full potential of diaspora remittances as a source of the much-needed investment capital. The study adopted a multi-pronged research approach, largely utilizing qualitative designs to collect and analyze data through questionnaires and interviews. A purposive sample of 150 respondents was used. The results obtained confirm that the Zimbabwean economy is yet to realize full potential economic benefits (investments) from its citizens domiciled abroad. The study has thus proffered some recommendations that the Zimbabwe government could introduce to boost her diaspora’s contribution to national development. The recommendations include confidence (trust)-building measures to convince the diaspora community to invest back home; awareness campaigns to highlight existing investment opportunities, and pro-active engagement with the diaspora community, among others.

Keywords: Diaspora, Investment, Investment capital, National development, Remittances

Cite this paper: Rangarirai Muzapu, Taona Havadi, Boosting Diaspora Remittances as a Key Source of Investment Capital: The Case of Zimbabwe, Management, Vol. 11 No. 2, 2021, pp. 27-37. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20211102.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

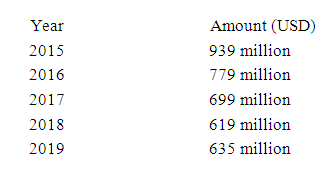

- Several scholars, such as Kuschminder (2016), Kuschminder (2011), Masiiwa and Doroh (2011) and Brinkerhoff (2012) have illustrated that diaspora remittances do accelerate economic growth in recipient countries. For instance, by eliminating credit constraints on the poor, improving the allocation of capital, facilitating infrastructure development, and substituting for the lack of financial development in recipient countries. In some cases, remittances constitute the biggest source of international financial resources, ahead of FDI. For instance, the 2018 UNCTAD Report showed that in 2017, global diaspora remittances at US$466 billion exceeded other major sources of external finance such as; portfolio investments (at $420bn); and overseas development assistance (at $190bn) as well as long and short-term loans (private and public; at $240bn) (UNCTAD Report, 2018). Zimbabwe is one of such countries where remittances from her nationals domiciled abroad constitute a significant source of international financial resources. According to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ), the diaspora remittances over the period 2015 to 2019 were as follows:The diaspora community also promotes and facilitates international trade by identifying and creating opportunities for exportable goods and services through ‘on the ground’ market surveys and market intelligence. It also promotes international tourism and the transfer of new knowledge and skills between economies (Ministry of Finance and Economic Development of Zimbabwe, 2 May 2021).According to the Southern African Political Economy Series (SAPES) Trust (2020), over the years, Zimbabwe has seen its citizens estimated to be between three and five million (the exact number of the Zimbabwean diaspora is unknown) migrating to other countries in search of mainly, employment and investment opportunities. Those who have migrated include highly skilled professionals like nurses, teachers, engineers, researchers, and medical doctors. Other categories of the Zimbabwean diaspora include; entrepreneurs, traders, students, and semi- and non-skilled workers. Most of them live and work in South Africa, the United Kingdom, Canada, Botswana, New Zealand, China, Australia, and the United States, among other countries. As shown by the diaspora remittance inflows in Figure 1 (ranging between USD619 million and USD939 million between 2015 and 2019), these Zimbabwean nationals living and working abroad have proved to be a key source of economic energy for Zimbabwe by way of remitting funds. The challenge, however, is on how best to implement means and strategies to unlock the full economic potential presented by this constituency, beyond the aspect of remitting funds for consumptive purposes. The Zimbabwean diaspora community's contribution to other economic sectors has not been evident despite ubiquitous potential in that regard, hence the contention of this paper that Zimbabwe is yet to realize full economic dividends from her citizens in the diaspora. The Minister of Finance and Economic Development alluded to this view in his 2021 National Budget Statement (The Zimbabwe Herald, 26 November 2020). He noted that the Zimbabwean diaspora presented a significant opportunity (or potential) for contributing to the development of the economy beyond the aspect of remitting funds for consumptive purposes. In this regard, the Minister pointed out that the government was in the process of drafting and implementing policies to better harness and utilize this resource (the potential presented by the diaspora community), particularly regarding nurturing the diaspora entrepreneurial potential.

| Figure 1. Zimbabwe Remittance Inflows |

2. Research Questions

- • Why is Zimbabwe not realizing the full economic potential presented by her citizenry in the diaspora?• What are the best potential vehicles/conditions that the government of Zimbabwe can implement to mobilize diaspora wealth to spur national development?

3. Motivation

- Global migration flows keep evolving and countries must live with this reality and put in place mechanisms to effectively attract the precious resources and economic potential that come along with migration. Respective governments should, therefore, facilitate favourable investment processes and operational mechanisms that accommodate emigrants to channel resources to their home countries. The high levels of remittance inflows registered by other countries across the world (for example, according to migrationdataportal.org, in 2020, India received remittances inflows that amounted to USD83 billion, China USD60 billion, Mexico USD43 billion, the Philippines USD35 billion, and Egypt USD30 billion), are a confirmation that with the right approaches, policies, administrative structures, incentives, discipline, and political support, it is possible for other countries to also increase their remittances inflows. Zimbabwe is not an exception in this case and should seriously investigate better ways to tap the full economic potential presented by her diaspora community. Zimbabwe should consider taking a leaf from countries with the best practices, ensuring a balanced mix of supportive policies that stimulate the diaspora's contribution to the domestic economy.

4. Methodology

- The study combined data from primary and secondary sources. Primary data was gathered through interviews from representative elements of the Zimbabwe diaspora across the globe, government ministries personnel, development agencies (based in Zimbabwe), monetary experts and economists, business analysts, industrialists, financial institutions (bankers), scholars, and independent private entrepreneurs. Some information was also gathered from seminars and meetings. A representative sample of 150 respondents was used. A purposive sampling approach was largely used to capture the right respondents; thus, specific and well-defined subjects (representatives) were targeted. It enabled the generalization of the findings to a population. It also facilitated the development of a detailed analysis of the problem under study. Secondary data sources included published articles, policy documents, and reports produced by various institutions and individuals. Due to the research objectives and requirements of the data acquired, the qualitative research approach outweighed other research designs in bringing out the much-needed information. Thus, qualitative data was much needed.

5. Diaspora Concepts, Theories and Models in National Development

- Poornima and Unnikrishnan (2015) described the word 'diaspora' as having its roots in the Greek word, 'diaspeirein', which means, 'to scatter across, or disperse'. Dispersal is a result of a combination of compulsion and choice. Thus, emigrations are a result of push and pull factors. Bartleby (2002) and Safran (2017) also stated that the word diaspora refers to 'citizens of a dominant country/city who immigrated to a conquered land with the purpose of colonization, to absorb the territory into the empire to plunder resources and send them to their homeland'. Birkenhoff (2011) viewed diaspora as immigrants who maintain a connection, psychological or material, to their place of origin. Safran (1991) sets up four criteria for the diaspora's existence: (i) expatriate communities that preserve a collective memory of the homeland; (ii) migrants perceiving the homeland of their ancestors as their true home, hoping to return one day; (iii) dedication to restoring the homeland; and (iv.) connection with the homeland that shapes their identity. The African Union Report (2005) defined the African diaspora as consisting: "… of peoples of African origin living outside the continent, irrespective of their citizenship and nationality, who are willing to contribute to the development of the continent and the building of the African Union.". Largely, the views took an economic point of view.The reasons (characteristics) behind emigration vary. Theorists have generally concurred that diaspora communities are formed over a period by several waves of migration and that each could have different or several causes at any given time. Butler (1998) put forward the idea that the diaspora is categorized based on the reasons behind dispersal. Sheffer's (2016) concept on the diaspora, noted that there were two types of diaspora namely; the Stateless Diaspora (migrants who are without States of origin) and State-Based Diaspora (migrants who are with states of origin). The State-Based tend to follow up on what is happening back home and may wish to invest or remit valuables. These are potential targets for any economic progressive-minded government.Bruneau (2010) defined three major categories of diaspora; the entrepreneur diaspora; religious diaspora; and the political diaspora. He observed that the three categories were shaped by reasons or interests that necessitated emigration. They would also maintain the interest of the country of origin. Bruneau (2010) further stated that entrepreneur diaspora constitutes the central element of the reproduction strategy that any government may wish to have. Bruneau (2010) contended that most of them emerged from a colonial context, in which the ruler assigned their various commercial and enterprise activities (Indians and the Lebanese in Africa, and, the Chinese in South-East Asia). This is an influential group that can play a positive catalytic role in economic development. In this case, the positives are glaring, and it, therefore, explains why many governments, Zimbabwe included, are finding it worthwhile to implement mechanisms to tap into the valuable resources from this constituency.Governments/states of origin mostly target the entrepreneurial diaspora (economic diaspora) as they can play a significant role in national development in the country of origin. The community is closely interconnected and productive as they share a common interest. It usually appraises the country of origin on important entrepreneurial business opportunities and threats (economic intelligence). The Chinese, Indians, Pakistanis, Jewish, Filipinos, and Lebanese diaspora are the best examples of this practice as their activities are visible in many countries, including in Zimbabwe.A majority of the diaspora, as observed by Van Hear (2014), understand that their presence in their respective countries is temporary and that they need to prepare at some point to return to their countries of origin. This category would, during their stay, work hard in preparation to return home. This may therefore be equated to migratory birds (economic diaspora) that flock and live together. Migratory birds (economic diaspora) share a concept that wherever they are, they need to prepare to return to their original place (country of origin) at some point in time. This, therefore, implies that the close-knit community shares vital information. They plan, coordinate and execute responsibilities together. They accumulate as much wealth as they can in preparation to return home or for family generational inheritance. It is the researchers' considered view that for economies of origin countries to tap maximum economic dividends from their respective diaspora communities as much as possible, there is a need for implementation of effective tailor-made policies by the respective central governments. It would be worthwhile for each respective government to institute central briefing points to capture the ideas and resources from the diaspora. This paper, thus, supports the idea of promulgating various mechanisms that may unlock the diaspora's full potential contribution to national economic development. The paper also highlights some policy gaps that should be attended to by the central government to that end.

6. Efforts in Boosting Remittances and Wealth from the Diaspora

- In recognition of the potential of diaspora remittance inflows, the Government of Zimbabwe, through the Central Bank, put in place several mechanisms to boost remittances. The RBZ, in 2005 (The Herald, 5 February 2005), established a company called Homelink to harness foreign currency from Zimbabweans in the diaspora by providing products and services that meet the investment and consumption needs of such people. Homelink is structured into four (4) business units, namely Proplink, Easylink Money Transfer (Pvt) Ltd, Investlink, and Masterlink Capital Services (Pvt) Ltd. Proplink is involved in real estate development (housing and land development); Easylink Money Transfer (Pvt) Ltd is an agent of Western Union International, responsible for money transfer services. Customers receive money sent from the diaspora through the unit's widely distributed branches located in cities, and some outlying areas. Masterlink Capital Services (Pvt) Ltd provides short-term financing needs for customers within and outside Zimbabwe. Lastly, Investlink promotes the investment needs of the diaspora by scanning for investment opportunities in the country and parcelling the opportunities to the diaspora for possible take up. In 2009, the RBZ issued the Diaspora Tobacco & Gold Production Financing Bonds to boost diaspora remittances. Tobacco bond-holders received capital plus interest as a single bullet payment at the end of the tobacco season. The Diaspora Gold Production Financing Bond was also issued to Zimbabweans in the diaspora to finance gold production by small-scale gold miners in return for interest when the producers sell their gold to the RBZ's gold buying arm, Fidelity Printers and Refiners.In 2016, the RBZ launched the Diaspora Remittances Incentive Scheme (DRIS) and further enhanced it in 2017. Under the scheme, in 2016, the RBZ introduced a 3 percent incentive to receivers of remittances in Zimbabwe who would receive funds sent to them via formal channels, that is, through registered money transfer agents. The incentive was increased to 10 percent of the funds received in 2017. The Diaspora Remittances Incentive Scheme was meant to encourage remittances through formal channels. The scheme benefitted both the money transfer agents and the receiver of the funds based on a 2% and 3% split. This was to assist in reducing the cost of receiving and sending remittances. The mode of payment was such that the agent was to pre-fund the payout and the RBZ would pay the incentive based on money received. The scheme witnessed an increase in the flow of remittances by a monthly average of US$45 million. However, it was discontinued without notice on March 27, 2019 (Financial Gazette, December 8, 2019, RBZ, March 2019).The RBZ has also introduced an Investment Desk to specifically cater for Zimbabweans living and working outside the country. The desk, which was established in 2018, seeks to facilitate the participation of Zimbabweans in the development of the country through the mobilization of investments into various economic sectors. Furthermore, the RBZ authorized commercial banks in Zimbabwe to open Diaspora Investments Accounts for Zimbabweans in the diaspora (The Herald, 7 February 2018). The accounts, designed to facilitate savings/investment and/or for holding funds earmarked for undertaking investment projects in Zimbabwe, would be funded from offshore and were entitled to a 7 percent Diaspora Remittance Incentive from the RBZ over and above the interest offered by the bank. However, the diaspora community was hesitant due to uncertainties exhibited in previous monetary and fiscal policies. They feared that when the RBZ has collected enough, it would force clients to convert their balances into a volatile local currency. They also feared that it would be impossible to withdraw their funds on demand since the RBZ admitted that they have previously raided some accounts to keep the country's cash-strapped Ministries running (The Zimbabwe Herald, April 20, 2009). The bank indicated that the practice was widespread. Prospective clients feared that the money might drastically depreciate before the withdrawal. It was also felt that withdrawals would be limited to a level that does not conform to their needs since the bank had set the minimum and maximum withdrawals thresholds. The regulations restricted the withdrawals without prior notice and valid reasons for use of the hard currency. Negative media coverage also fuelled the rejection of the initiative. In the end, the prospective clients were not keen on receiving or depositing money in bank accounts or formal systems.In June 2019, the Minister of Finance and Economic Development outlawed the use of multiple currencies, which move shattered the incentive schemes earlier introduced by the RBZ (RBZ, June 2019). The move also defeated some of the previous initiatives. The policy reversal fuelled scepticism about using the formal system for purposes of sending remittances to Zimbabwe.

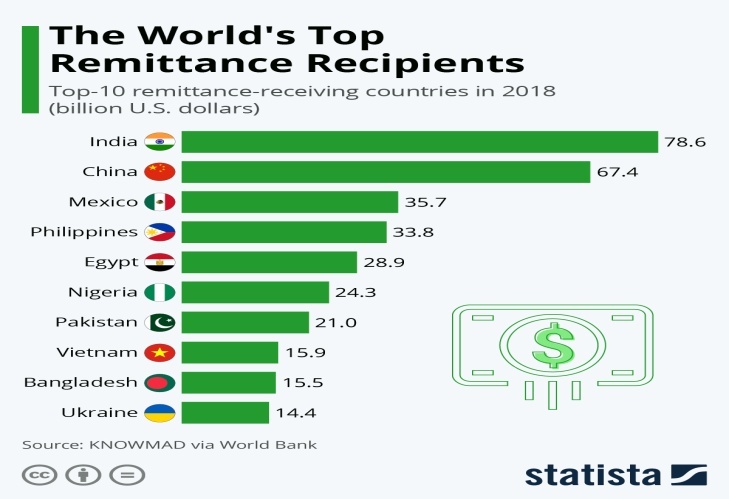

6.1. Global Remittance Trends

- According to the World Bank 2020 Report, globally, the top remittance recipient countries in 2019 were India ($79 bn), China ($67 bn), Mexico ($36 bn), the Philippines ($34 bn), and Egypt ($26.7 bn) among other countries. In the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) region, the leading recipients of remittances were Egypt ($26,791 million), Kenya ($2,819 billion), Tunisia ($1,912 billion), and DR Congo ($1,823 billion).The World Bank (2019) also reported that remittances to the East Asia and Pacific region grew by 7 percent to $143 billion in 2018, showing a 5 percent growth from 2017. In 2017 and 2018, remittances to Europe and Central Asia grew by 22 and 11percent, respectively. Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan benefited from the sustained rebound of economic activity in Russia and the region and posted increased remittances. Ukraine, the region's top remittance recipient, received a record of more than $14 billion in 2018, an increase of about 19 percent from the previous year. The margin, however, reflected a revised methodology for estimating incoming remittances, as well as growth in neighbouring countries' demand for migrant workers which Ukraine citizenry took advantage of.Remittance flows into Latin America and the Caribbean grew by 10 percent to $88 billion in 2018. Mexico's inflows improved by 11 percent and posted $36 billion in 2018. Colombia and Ecuador posted 16 and 8 percent growth, respectively. Guatemala posted 13 percent and the Dominican Republic and Honduras both posted 10 percent increases, reflecting robust outbound remittances from the United States (WB, 2019). The WB Report (2019) further noted that in 2018, remittances to the Middle East and North Africa grew by 9 percent to $62 billion. The growth was driven by Egypt's rapid remittance growth of around 17 percent.In 2018, remittances to South Asia grew by 12 percent to $131 billion, surpassing the 6 percent growth in 2017. The upsurge was driven by stronger economic conditions in the United States and a pick-up in oil prices, which had a positive impact on outward remittances from some Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. In India, where a flooding disaster in Kerala in 2018 likely boosted the financial help that migrants sent to families, remittances grew by more than 14 percent to $78.6 billion. In 2018, Pakistan remittances grew by a moderate 7 percent to $21 billion. In 2018, Bangladesh's remittances sharply rose by 15 percent to $15.5 billion (WB, 2019).

| Figure 2. World's top remittance recipients (World Bank-KNOMAD staff estimates, World Development Indicators, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Balance of Payments Statistics) |

7. Discussions on Challenges and Possible Initiatives

- The survey has shown that the Zimbabwean diaspora has faced obstacles that might have frustrated and discouraged them from fully participating in the country's economic development. Monetary Policy Inconsistencies The study noted that one of the roles of the Central Bank of a country is to safeguard the stability of a currency through the application of necessary financial instruments. The primary objective is to achieve and maintain price and financial stability. By doing so, the currency would be protected from high inflation and loss of value. A stable currency can be relied upon in future markets when making predictions and investment decisions. It can help economic players to predict the potential gains and/or losses of their activities and decisions. It creates investment confidence as it brings relief to business operation costs (Gauvin, 2013). When the value of a currency is unstable, it discourages saving and increases production costs. This will give rise to suppressed production levels, high speculative tendencies, and consequently, continuous price hikes (Ludwing and Mises, as quoted by Forbes, 2019). Therefore, it is in the best interest of the central financial institution to keep prices stable by maintaining the value of the national currency. Keeping both currency and prices stable will encourage more business and attract investments from the local and international markets. It will also lure the diaspora to engage in meaningful development in their homeland. The consistency of such policies will advance the growth of the economy and enrich the operating environment. However, of late and currently, the Zimbabwe situation has fallen short of the best economic playing field on the score of policy consistency though it has improved significantly (openknowledge.worldbank.org).Since the year 2000, the instability of the Zimbabwean currency on the international exchange market has fuelled uncertainties regarding investment and production in the country. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) has tried to fix the challenges, but the problems seem to persist in the short-medium term. The currency continues to lose value against major currencies, particularly up until mid-2020. Traders argued that the system was manipulated. In other words, they claimed that it cannot sustain the market pressures. The fixed exchange rate system was quickly rendered useless when the market rates were always ahead of the fixed rate. Consequently, the parallel market (black market) flourished. The auction system did not achieve the desired results (Munzara, 2015). In February 2019, the RBZ, through Statutory Instrument (SI)133/2019, established an inter-bank foreign exchange market to formalize the trading of the Real-Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) balances and bond notes with the US$ and other currencies on a willing-buyer-willing-seller basis. The RTGS was not received with confidence by the market. In an attempt to quench the fires, the multi-currency system was adopted. The system had its fair share of challenges as that effectively meant that the country was losing control in the realm of monetary policy, and thus its sovereignty. With the gap between official and parallel exchange rates widening, in June 2019, the RBZ abolished, through SI142/2019, the use of multiple currencies and declared the local currency sole legal tender ostensibly to restore RBZ monetary control and tame inflation (RBZ, 2019). The RBZ pegged an illusionary 1:1 parity against the US$ and separated bank accounts into Nostro foreign currency accounts (FCAs) and RTGS FCAs. In July 2019, the RBZ once again allowed the use of foreign currencies for local transactions by few stakeholders as a policy shift from the prior circular, under Statutory Instrument 142/2019. The monetary authorities then established an inter-bank foreign exchange market, but the solution came too late (as a reactive mechanism) when the parallel market had long eroded the purchasing power of consumers. The re-introduction brought challenges in the form of multi-tier pricing by businesses, speculative pricing, and loss of government revenue, valuation and accounting difficulties, asset-liability mismatches, and negative investor confidence, among other problems. In March 2020, the fiscal authorities opened the floodgates for the wider market to use a multi-tier currency system, but it then fixed the exchange rate to US$1: Z$25 and later introduced the auctioning of foreign currency.In essence, the systems continued to be recycled as authorities sought the best strategy, albeit without success. This, however, would be done in a relatively short space of time (RBZ, The Zimbabwe Herald, 21 May 2020), a factor that sent negative signals to the market. The mainstream formal banking system became volatile, and customers were increasingly hesitant to put their hard-earned money in the formal banking system. Economists generally agree that a workable stable exchange rate system is a key pillar in any functional economy. Such an exchange rate augurs well for a stable economic pulse rate, allowing economic players to make medium- and long-term plans. Clearly, with the inconsistencies highlighted above, Zimbabwe's economic pulse rate suffered. During the period under review, the country witnessed significant liquidation and downsizing of companies as well as the capital flight to various destinations. Investors considered the investment environment to be unsustainable for continued business operations as the local and foreign currency shortages became more acute. The local currency also began its free fall in value against major currencies and inflation rose from a single-digit to six-digit rate. Meanwhile, the fiscal authorities amended the monetary positions to make it mandatory for the payment of import duty for selected imports to be done in foreign currency and for companies to pay taxes in the currency of trading. Fundamentally, these developments opened floodgates to price instability and value disruption. In these instances, investors, the diaspora, pensioners, entrepreneurs/businessmen, employees, savers, and members of the public lost their real incomes and earnings, a situation that has led many businesses to collapse and consumers to lose their purchasing power. A significant number of people lost money through banks. Furthermore, the arbitrary conversion of clients' foreign currency balances into local currency saw the bank balances being eroded by rising inflation. Besides the foregoing, there was also the closure of some banks without compensating clients on the real market value, closure of dormant diaspora accounts, and cash withdrawal limitations. Overall, the abrupt policy shifts undermined investor confidence. However, if the monetary challenges are not addressed well, the country may continue to lose potential investments as well as capital flight from the already established businesses. This paper argues that authorities should do everything within their powers to adopt policies that ensure a stable exchange rate system.Information Gaps on Investment OpportunitiesFor one to invest in a certain field, full information about the opportunities, threats in that sector juxtaposed against one's strengths and weaknesses, is a key determinant factor. Through this study, the Zimbabwe diaspora community indicated a lack of complete information on Zimbabwe's online platforms necessary to make sound decisions. They indicated challenges in accessing credible home-based sources of information. The few available sites were generally outdated and sometimes not in sync with prevailing situations on the ground. A survey of the Government of Zimbabwe websites and links by the researchers generally showed outdated information, not enough to trigger effective decision-making processes. Furthermore, most Zimbabwean embassies around the globe are short of updated investment information on their online platforms, making them ill-prepared to assist in that regard. Most embassy websites were found to contain very limited information. This could have been a useful platform (if updated). This calls for the government of Zimbabwe, its embassies, and agencies to relate to making frantic efforts to connect with nationals domiciled abroad through online platforms and, thus, disseminate updated information to citizens abroad. Embassy networks and communication platforms should be informative and educative to lure would-be investors.Lack of Appreciation from Home CountryIt is noteworthy that, apart from regular skilled and non-skilled individuals, the Zimbabwean diaspora community consists of asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, refugees, and dual nationality holders. It was the finding of this study that, many a time, Zimbabwean immigrants in these latter categories would speak negatively about their home country, sometimes inventing unfounded make-believe allegations in the hope of increasing their chances to be granted residence statuses in foreign lands. They would play the devil's advocate against their home country, instead of being goodwill ambassadors of the country. It is, therefore, important for the government and its embassies to reach out to this constituency and convince them to embrace their home country's development efforts.For those holding dual nationalities, before the alignment of the country's laws with the 2013 National Constitution, the Act prohibited the simultaneous holding of Zimbabwean citizenship and that of another country by any citizen (New Zimbabwe, 27 February 2019). The situation presented a legal vacuum that entrenched the feeling of alienation for such members of the diaspora community. They would feel unwanted and would, thus, feel less obliged to contribute to the country's economic growth. However, the situation was addressed. What is now unknown is whether dual nationality holders' investments will qualify for either foreign or local investment incentives. The categorization should lead to convincing them to invest in their homeland country.Through this study, it was observed that among the diaspora, such as members of the Zimbabwe diaspora community, that is, those in the categories highlighted above, some established professionals are earning good incomes, owning reputable foreign-registered companies, living comfortably, and have invested in their careers, and, therefore, have the potential to initiate development projects in their country of origin (Zimbabwe). This group may need to be convinced and/or persuaded to invest in the home country.Policy Consistencies and Security of InvestmentsInvestors, including Zimbabweans domiciled in foreign lands, would always wish to commit their resources to a market that is stable and predictable in terms of policy and projected returns on capital. Markets where conditions make it difficult for investors to project their earnings will always lose out in terms of investment inflows. Therefore, a more conducive or appropriate operating environment is ideal.In Zimbabwe, especially before November 2017, there were concerns over the country's policy inconsistencies and lack of clarity on investment policies. The study observed that the general perception of Zimbabwe is that of an unstable investment environment that is characterized by overnight changes in laws and agreements. It will require concerted efforts to undo this attitude, inspire confidence and achieve significant inflows of Chinese investment for economic stability and growth. Many a time, top government officials, including Ministers, issued conflicting investment policy interpretations publicly. This was particularly pronounced in respect of the Indigenization and Economic Empowerment Act (New Zimbabwe, 25 December 2015, The Standard, 3 April 2016). Such tendencies bred an unpredictable investment environment in which investors felt insecure. This would cause uncertainty and unpredictability, especially for investors interested in long-term, capital-intensive businesses. Consequently, investors may adopt a wait-and-see approach, withholding their capital investments.It is, therefore, imperative that the government thoroughly consults concerned stakeholders whenever making critical policies to achieve the necessary buy-in. Once a policy has been adopted, there is a need for consistency in terms of interpretation and implementation (practice) to attract long-term investment capital into the economy. Efforts should be made to make the environment stable and solid enough for businesses to flourish. A stable business environment attracts capital.Inclusive Investment PoliciesIt is quite common that when countries design their investment policies, the primary target is Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). However, diaspora communities are least thought of in that regard, even when the diaspora communities can venture into key investment projects in their home countries. The study found out that in some instances, the diaspora communities are also left out in programs aimed at empowering the local people of the home countries. In the case of Zimbabwe, the investment policies were targeted at attracting FDI, whilst the Indigenization and Economic Empowerment Act was silent on the role of native Zimbabweans leaving outside the borders. At present, as the study found out, the general view within the diaspora is that the government's investment promotion schemes are largely fashioned for foreign investors as opposed to local investors and the diaspora community. Furthermore, the environment is also viewed to favor large firms more than start-ups. Tailor-made schemes targeting the diaspora community could stimulate significant investment from this constituency. It is the considered view of this paper that investment and domestic economic empowerment policies should allow the participation of all the citizens, regardless of their location. In that respect, it would not be far-fetched to propose diaspora inclusive investment and domestic empowerment policies. Such an approach allows remittances to be directed towards national strategic projects as opposed to the traditional consumptive route.Establishing Trust Through Constructive EngagementsGenerally, the diaspora would want to invest in their countries of origin but may be deeply sceptical for some reason. As this study established, one of the possible reasons why Zimbabweans in the diaspora may not be keen to invest back home could be due to a lack of confidence and trust in the prevailing situation in the country. In some cases, the lack of confidence and trust-flows from the absence of accurate official information on policy positions and opportunities for possible take up. Zimbabweans in the diaspora, as stated above, have generally been assumed to be anti-government (The community in Western countries has staged several anti-government demonstrations/activities at embassies). Over the years, there has not been a noticeable attempt on the parties to engage constructively. The Zimbabwean diaspora has largely relied on the public media as the primary source of information on the situation back home. This was not ideal considering some media deficiencies bordering on over-exaggeration, dis-information, and misrepresentation of facts. This could be resolved via frequent official engagement between the government and the diaspora community as a platform to provide accurate information about the situation. For instance, the government, through embassies abroad should frequently engage with the diaspora community through a variety of communication platforms. The Embassies can hear out the diaspora community's challenges and aspirations and explain government policy positions on matters of concern. This may go a long way in building the diaspora's confidence in government dealings. This engagement would stimulate the exchange of knowledge, expertise, and experience between the diaspora and the mainstream development agencies. The knowledge and expertise sharing is of great essence as it can stimulate joint development activities in the future.One possible way to facilitate engagement between the government and the diaspora community would be hosting business seminars (online or face-to-face) in areas where there are sizeable Zimbabwean diaspora communities. The Embassies may also organize engagement events that include business conferences, sports tournaments, fashion shows, musical/film concerts, arts, and cultural fairs, as well as diaspora networking galas, among others. Through such events and/or platforms, top business or opinion leaders in Zimbabwe or any other country can be invited to mentor the diaspora to set up sustainable businesses back home and/or abroad and highlight trade opportunities. The government can also derive maximum value through such platforms and share with the diaspora community its economic agenda. The common purpose would be to share accurate information on business opportunities and sharing practical experiences from businesses operating in Zimbabwe. The Missions should have an effective program of tours of the host country. Such tours would be multi-purpose in nature. The tours would endeavor to initiate market studies/investigations, solicit foreign investment consistent with the objectives of the homeland government, identify, and brief potential investors within the diaspora community.In this regard, embassies would need to be adequately resourced to meet the costs entailed. For example, the researchers have observed that some African embassies in China, such as those of Rwanda, Zambia, Madagascar, Ghana, South Africa, and Kenya, among others, coordinate/sponsor cultural groups that are formed by resident students/citizens from their home countries, to perform in various provinces around the country showcasing their countries' investment opportunities. Besides, the embassies regularly host ‘Culture Day’ events and funfairs where they invite their resident citizens to participate. These country-marketing vehicles have, in a way, exposed their countries to a wider audience (their diaspora and locals) with the potential to positively contribute to the country's socio-economic development. Citizens are encouraged to partner with potential investors to invest in their homeland country. Thus, these embassies have realized that an engaged diaspora can be an asset in promoting economic growth, hence the massive event sponsorships. As for Zimbabwean embassies abroad, much effort should focus on engaging citizens domiciled abroad. To accomplish this, adequate resourcing should be availed. Apart from insufficient funding, existing treasury instructions guiding the embassies' financial expenditures need to be reviewed to accommodate this emerging expense with respect to embassies' operations.Building Confidence and Timely Action on GrievancesConfidence and trust between the government and its citizenry are built largely through the positive actions of the government. These include, among others, enacting and implementing policies that benefit citizens, embracing accountability and transparency in public transactions, and fighting corruption in a firm, fair, and just manner. That would be critical in winning the confidence and trust of citizens. When the government demonstrates concern for its people, wherever located, the citizens likewise, would be largely inclined to respond positively to the government programs.It is also important that whatever initiatives are undertaken by the government should be headed by people of good repute and not those whose names are embroiled in historical corrupt activities. The leading people should pass credibility/competency tests. This relates to proposals mentioned earlier which suggested that the government, in partnership with the diaspora communities, could organize business seminars where the Zimbabwe business leaders and successful entrepreneurs can exchange and share ideas and information on business opportunities back home. Therefore, the study noted that there is a need to identify patriotic and credible individuals who can serve as go-betweens in the government's quest to reconnect with the Zimbabwe diaspora community. The aim is to complement the efforts of the embassies to remove the deep-rooted suspicions between the government and the diaspora.Enhanced Coordination within Government DepartmentsThe study noted that before 2018, the Diaspora desk was housed under the former Ministry of Economic Planning, then the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, and later the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. The RBZ also houses the Diaspora desk. These adjustments seek to increase the visibility of diaspora issues by integrating them within the country's economic diplomacy thrust. This confirms that the Government of Zimbabwe may have taken note of the potential of the diaspora community to contribute meaningfully to the development of the country. However, there is a need to go a step further by widening the scope of the Ministry's departments and establish an office, institution, or think-tank which links directly with the diaspora regularly. The institution should be adequately resourced to deal with the perceived demands. The institution should act as a one-stop platform that informs, educate, train, motivate, and provide business intelligence. Moreover, the institution should act as a research center or inquiry office for the diaspora community. The think-tank institution would help steer a road map based on research practices upon which new policies and strategies can be formulated. Furthermore, hotlines or service care centers (dedicated online portals) can be established. Website links and portals can also be developed to enhance effective communications.Incentives to Attract Diaspora InvestmentThe research has observed that an attractive and sustainable business environment should be created for private investors to commit their funds towards investments in Zimbabwe. The incentives offered should be enticing enough to make it worthwhile for investors to choose to invest in the Zimbabwean economy. It should be noted that for policies to achieve their desired impact, they must be communicated to and understood by the concerned stakeholders. The Chinese have a metaphor that they use to attract meaningful investment: It goes like this, "building a nest for the bird to lay the golden eggs". The metaphor acknowledges that investment can only be attracted to a safe, stable, least costly and profitable environment, supported by predictable legislations, preferential policies, and incentives. Incentives may be in the form of fiscal and non-fiscal policies that attract the establishment of investments in perpetuity. For instance, reduced tax rates for defined trades and projects, reduction of corporate income tax for enterprises set up by diaspora investors, and some tax holidays, could be extended as incentives to the diaspora community businesses. Import duty exemptions on machinery and other capital equipment imported for investment in specific areas prioritized by the government among others could fall in the same bracket.Issue of Share Capital and Investment ModelsThe study revealed that the Government of Zimbabwe was in the process of privatizing some parastatals. While privatization of parastatals may bring about more efficiency, it must be kept in mind that the Government of Zimbabwe must maintain its ownership of some strategic industries since they are of security interest and a source of perpetual revenue. Privatization may also be a window to empower the diaspora through the establishment of offshore consortiums which can buy shares in the privatized companies. This will enable the country's economy to be kept in the hands of locals.Furthermore, the government could partner with credible companies or institutions to mobilize funds from the diaspora for specific projects through the stock exchange. For example, if it would cost USD1 billion to set up a power generation plant, the diaspora community could be allowed to buy shares into the company. The same concept could be applied to other sectors of the economy, enabling the diaspora community to own portions of commercialized companies through similar initiatives. The challenge is on identifying credible institutions, but this can be overcome through the confidence-building mechanisms between the government and the diaspora community. Due diligence (extended vetting) on such credible companies would be ideal, coupled with an enunciated legal framework for reference.

8. Conclusions

- It is evident that remittances if properly harnessed, could contribute immensely towards the socio-economic development of a nation. From the facts above, one can safely argue that the authorities in Zimbabwe should provide an enabling environment that allows the country's citizens abroad to invest in strategic economic programs and projects back home. These policy interventions should include, inter alia, consistent monetary and investment policies which guarantee the security of investments. For this to be realized there ought to be inclusive engagements between various stakeholders during the formulation of key policies. This would have a net positive effect on building trust and confidence in the systems. The creation of a Diaspora desk in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Trade is not an end in itself. It would be prudent for the Desk to be fully capacitated to facilitate investments for Zimbabwean citizens abroad.Whilst the government is duty-bound to provide an enabling investment environment, financial literacy ought to be instilled in the larger Zimbabwean diaspora community for them to diversify their investments from the common property market into other sectors of the economy such as manufacturing, service industries, and agriculture. In this regard, it would be ideal for Zimbabwe to compare notes with other countries who have mastered the processes.

Possible Way Forward

- More elaborate studies will help identify more effective practical mechanisms that can convince the diaspora to invest in homeland countries. The government of Zimbabwe should, therefore, regularly (where appropriate) reform its policies by identifying and filling in gaps accordingly.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Appreciation goes to all who gave their time, advice, and encouragement. Special mentioning goes to Memory Muzapu and Memory Havadi for their patience, and insightful comments.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML