-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2020; 10(2): 35-45

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20201002.01

The Relationship between Job Insecurity and Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Employee Morale and Psychological Strain

Anthony Frank Obeng1, Prince Ewudzie Quansah1, Eric Boakye2

1School of Management, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China

2Credit Department, Pan-African Savings and Loans, Kumasi, Ghana

Correspondence to: Anthony Frank Obeng, School of Management, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Economic instability and downturn mostly promulgate job insecurity leading to turnover intention. Savings and Loans companies in Ghana have recently had challenges in turnover which greatly affects their productivity. Owing to this, this study aims to investigate the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention with the mediating mechanism of psychological strain and employee morale. With 341 valid responses received through a structured questionnaire, hierarchical multiple regression was employed to validate the hypotheses. Based on empirical data from Ghana and drawing on social exchange theory the results show that, job insecurity positively and significantly influenced turnover intention. Moreover, employee morale as a motivator partially mediated job insecurity and turnover intention relationship. Also, psychological strain as a form of stress fully mediated the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention. The policy recommendation is also discussed.

Keywords: Job insecurity, Turnover intention, Psychological strain, Employee morale, Savings and Loan Company

Cite this paper: Anthony Frank Obeng, Prince Ewudzie Quansah, Eric Boakye, The Relationship between Job Insecurity and Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Employee Morale and Psychological Strain, Management, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2020, pp. 35-45. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20201002.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Turnover behavior is determined by turnover intention, hence organizations are heavily hit by the loss of highly trained qualified labor force which may lead to low productivity, competitiveness, and sometimes innovation as a result of turnover (Çınar, Karcıoğlu, & Aslan, 2014). According to Tett and Meyer (1993), turnover intentions is a conscious and deliberate willfulness to leave the organization. Vandenberg and Nelson (1999) define turnover intention as an ‘individual’s own estimated probability (subjective) that they are permanently leaving the organization at some point soon’. However, decisions by employees to quit an entity in most cases are unwanted consequences for the organization and the employee since both are affected tremendously in several ways (Rahman & Nas, 2013). Given this, employee turnover has been a bone of contention in organizational behavior research in the past decades (Lee, Gillespie, Mann, & Wearing, 2010). Consequently, the outcome of turnover brings about recruiting and training of new staff which has a significant cost effect on organizations (Rana & Abbasi, 2013). Moreover, organizational effectiveness, efficiency, and productivity are highly affected by turnover. Consequentially, the corporate image of an organization suffers negatively when turnover is increasing and this can contribute to job insecurity. However, once an individual is perceived to be secure and safe, achieving the goals and objectives of daily activity becomes desirous (Abolade, 2018). To understand the ramifications surrounding the upsurge of turnover in contemporary organizations, the intention to leave an organization should be addressed. Abolade (2018) posits that job insecurity is a feeling employees assume as a probable threat to a perpetual present job. More specifically, job insecurity is a persistent job stressor (Mauno, Leskinen, & Kinnunen, 2001), which influences an employee’s well-being (Hellgren, Sverke, & Isaksson, 1999). Moreover, it is a great stressor precisely in times of economic downturn (Cheung, Gong, & Huang, 2016). Although earlier studies have investigated job insecurity as an independent predictor of psychological strain, it is worth examining how job insecurity may relate to psychological strain to predict turnover intention. This has become necessary since psychological stress interacts negatively with job satisfaction (Jex, 1998). Even though several job stress has been occasioned by job insecurity (Kahn & Byosiere, 1992), the most comprehensively assessed negative emotion is the psychological strain (Cheng & Chan, 2008; Sverke, Hellgren, & Näswall, 2002). Generally, global labor force turnover that downgrades productivity and exterminates morale is a serious problem (Huffman, Casper, & Payne, 2014). Employees’ behavior gets sparked when there is high morale dwelling in an organization (Dash & Mohanty, 2019). Additionally, low morale may cause high absenteeism and turnover (Tiwari, 2014). However, studies conducted on job insecurity and turnover intention overlooked the mediating influence that affects employee attitudes and behaviors such as psychological strain and employee morale. Drawing on social exchange theory (SET), we hypothesized and tested a model in which job insecurity affects turnover intention through employee morale and psychological strain in the Ghanaian savings and loans companies’ perspective. Given this, the study aims to investigate the; (a) effect of job insecurity on turnover intention (b) the mediating effect of employee morale and psychological strain (c) effect of employee morale and psychological strain on turnover intention of the employees of savings and loan companies.

2. Literature and Hypotheses

2.1. Turnover Intentions

- Retaining employees is a challenge faced by organizations in the quest to achieve organizational goals. The length of period at which an employee decides to stay with an organization denotes turnover intention (Gul, Ahmad, Rehman, Shabir, & Razzaq, 2012). McCarthy, Tyrrell, and Lehane (2007) assess that intentions are the most immediate determinants of actual behavior, hence, intention to stay or leave has a relation with actual turnover (Strolin-Goltzman, Auerbach, McGowan, & McCarthy, 2007; Van Schalkwyk, Du Toit, Bothma, & Rothmann, 2010). Moreover, Carmeli and Weisberg (2006) posit that turnover intentions denote three elements pertaining to the withdrawal cognition process (i.e. thoughts of quitting the job, the intention to search for a different job, and then intention to quit). Though intent to leave differs from actual turnover, it has been identified by researchers that this intent has an instantaneous causal effect on employee turnover (Rahman & Nas, 2013). Consequently, the perception of turnover predictors is considered essential in order to reduce its negative effect on organizational performance (Low, Cravens, Grant, & Moncrief, 2001). However, several factors affect employee turnover intention in an organization, for instance, employee engagement (Macey & Schneider, 2008), growth and development (Grawitch, Trares, & Kohler, 2007), positive feelings and trust (Maertz Jr, Griffeth, Campbell, & Allen, 2007), job prospects (Munasinghe, 2006), pay compensation (Heckert & Farabee, 2006), job enrichment and job stability (Luna‐Arocas & Camps, 2008). Turnover intention can either be voluntary or involuntary. When employees decide to leave an organization, voluntary turnover has occurred while the intent to remove an employee from a position by the organization is said to be involuntary. According to Takase (2010), turnover intention is defined as ‘employees’ willingness or attempts to leave the current workplace voluntarily. Subsequently, some researchers have identified turnover intention as a direct mediator of actual turnover. Others also view it as an indication of organizational malfunctioning (Vigoda-Gadot & Ben-Zion, 2004) or a sign of organizational ineffectiveness (Larrabee et al., 2003). It is worth noting that turnover intention has been applied in the extant literature as a suitable substitute measure of actual turnover e. g. (Byrne, 2005; Firth, Mellor, Moore, & Loquet, 2004; Knudsen, Ducharme, & Roman, 2006). Studies have revealed that the intensity of turnover intention is positively associated with actual turnover (Brough & Frame, 2004).

2.2. Job Insecurity and Turnover Intention with Employee Morale as a Mediator

- Certainly, turnover among employees is a key challenge that concerns organizations about job insecurity. De Witte (2005) articulates that job insecurity fills the gap between employment and unemployment which denotes the feeling of unemployment threat by employees. Job insecurity is defined by Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt (1984) as “perceived powerlessness to maintain desired continuity in a threatened job situation”. Therefore, this situation leads to negative reactions by employees (Çınar et al., 2014). However, Putra and Suana (2016) referred to the general concern about the future existence of work as job insecurity. In this case, when employees feel dissatisfied and insecure which affects the employee situation, accordingly, it tends to increase turnover intention (Hanafiah, 2014). Furthermore, research has revealed that job insecurity predicts job dissatisfaction among employees (Ashford, Lee, & Bobko, 1989; Davy, Kinicki, & Scheck, 1991). Besides, employees who perceive job insecurity will probably get involved in work withdrawal behaviors (Probst, 1999), which mostly influences employee turnover (Ashford et al., 1989; Davy et al., 1991). Also, Arijanto, Marlita, Suroso, and Purnomo (2020) posit that turnover intention turns to be high if workers feel insecure at work. For instance, empirical studies have consistently established that job insecurity and turnover intention are inversely related (Borg & Elizur, 1992; Jacobson, 1991). Therefore, from the above discussion, we hypothesized that;H1: There is a positive and significant relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention.

2.3. Job Insecurity and Turnover Intention with Psychological Strain as a Mediator

- Job insecurity and turnover relationship can be explained by the inclination of employees to withdraw from stressful situations (Ashford et al., 1989). Hur and Perry (2014) contend that job insecurity is anticipated to affect a diversity of organizational behaviors such as productivity, turnover, and resistance to change. Job insecurity has motivated the occurrences of numerous psychological stressors (Kahn & Byosiere, 1992; Shanker, 2019). Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt (1984) assessed that in an era of economic downturns, job insecurity is considered to be a chief stressor. Moreover, job insecurity comes with a threat of keeping a job to future, and this experience and qualms are described as a stressor (Barling & Kelloway, 1996). Also, job insecurity has been acknowledged as a kind of work-related stressor (Lim, 1997) which is a possible disadvantage towards employee job attitudes and behaviors. However, most research, including a meta-analysis by Sverke et al. (2002), has linked job insecurity to strain (Ashford et al., 1989; Kinnunen, Mauno, Nätti, & Happonen, 2000)]. Furthermore, it has been opined by Fullerton, McCollum, Dixon, and Anderson (2020) that job insecurity behaves like a chronic stressor in which negative impacts develop effectively as the time of exposure increases. Hence, it is hypothesized that; H2: Job insecurity positively and significantly influence psychological strainExtant literature shows that turnover intention is related to job insecurity, work stress, and work environment. However, it is confirmed in the hospitality industry that the psychological strain is a possible predictor of turnover (Tromp, van Rheede, & Robert, 2010). Pindek, Arvan, and Spector (2019) in their meta-analysis found that a person’s psychological, physical, and behavioral responses to stressors are said to be strains. Psychological strain or emotional exhaustion is seen as the basic dimension of burnout caused by stress (Maslach, 1998). A precursor of psychological strain was found to be organizational support, however, it is indicated that it has a direct relationship with turnover intention (Jawahar & Hemmasi, 2006). Moreover, many studies in other human relation sectors positively show psychological strain and employee turnover relationship (Hochwarter, Perrewé, & Kent, 1995). Hence, we proposed that;H3: Psychological strain positively and significantly influence Turnover IntentionH4: Psychological strain mediate job insecurity and turnover intention relationship

2.4. Job Insecurity and Turnover Intention with Employee Morale as a Mediator

- Coughlan (1970) opines that the total viewpoints, attitudes, fulfillment, and self-assurance that is felt by employees at work are viewed as employee morale. The definition of Morale related to job situation was provided by Guion (1958) as “the extent to which an individual’s needs are satisfied and the extent to which the individual perceives that satisfaction as stemming from his total job situation”. Some studies have been cross-disciplinary in context, including the medical sector, hospitality and tourism, financial services, transportation, and retail (Bakker & Leiter, 2010). But a study carried out on a financial perspective, specifically, climaxes vital facets of employee morale. When employee’s morale is low, an increase in the cost of operation is inevitable (Salanova, Agut, & Peiró, 2005) which leads to turnover (involuntary) and in turn, leads to job insecurity. Shaban, Al-Zubi, Ali, and Alqotaish (2017) posit that job insecurity is sometimes ascribed to several factors such as low morale. Bohl (1989) postulated that “poor morale is contagious” and it may begin with one dissatisfied employee and broaden into a general malaise. Also, morale spreads from department to department and finally infect the entire organization. However, insidious as it may be, poor morale is reversible. We, thus, hypothesize that;H5: Job insecurity has a negative influence on employee moraleAn increase in employee turnover is a result of a costly sign of employee low morale, making employees unhappy, leading to no motivation to stay (Shaban et al., 2017). According to Rukshani and Senthilnathan (2015), low employee morale and productivity decline are frequently assessed and it is caused by employee turnover. Studies have disclosed that new leadership ideas have positive effects on employee morale and have significantly limited employee intention to leave their organization (Ngambi, 2011; Verma & Kesari, 2017). With good managerial practices, employee morale becomes positive and in turn, reduces the turnover intention rate. Depicting that high employee morale influence employees to stay while low employee morale influence turnover intentions of employees. We, therefore, hypothesize that;H6: Employee morale negatively influence turnover intentionH7: Employee morale will mediate the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention

2.5. Theoretical Framework

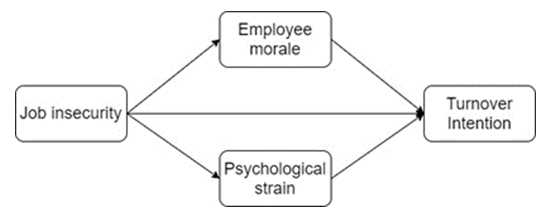

- The voluntary actions that are inspired for a person’s returns are expected to bring and typically do bring from others, which is based on a central premise that the exchange of social and material resources is a fundamental form of human interaction (Blau, 1964). Since constructs under investigation in this study are positive and negative initiating action, it is imperative to use SET in espousing the relationships that exist between them. Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of the study. The framework depicts job insecurity to have a direct effect on turnover intention. Job insecurity directly influences employee morale and psychological strain, while employee morale and psychological strain having a direct effect on turnover intention.

| Figure 1. Proposed framework |

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

- This research relied on a questionnaire to collect data on how savings and loans company’s employees in Ghana perceive the effect of job insecurity on turnover intention. Permission was sought and meetings were held with employees of the various branches together with the managers of the Savings and Loans companies. The study’s objectives were explained and we offered assurances of confidentiality and non-loans specific aggregation of data for purposes of analysis. The total accessible population of 17 Savings and Loans companies was 600 employees who met the selection procedure used across 60 branches. The procedure for the selection demands that: (a) a participant had worked with the company for at least six months and (b) a participant was a permanent staff of the company. The simple random sampling method was used to select participant samples from each branch, resulting in a sample size of 341. In sampling, Krejcie and Morgan (1970) sampling table and formula which uses a population proportion of 5% and a confidence level of 95% was used. After determining the sample size that corresponded to the population size of each branch, members of the overall sample were selected. The population members for each bank were assigned codes that were listed in IBM SPSS version 23. In the SPSS framework, the Random Sampling Function was used to select codes to make up the sample size for each branch. The survey was conducted within 14 weeks.The results from the survey on the information of the respondents showed that the majority of the respondents totaling 240 (70.38%) were males while 101 (29.62%) were females. The study also revealed that respondents with a bachelor’s degree qualification totaled 192 (56.30%), and Diploma certificate qualification totaled 149 (43.70%). Information on the length of service of respondents also showed that 96 (28.15%) of the respondents had been with their company for 12 years and above, 75(21.37%) of the respondents had worked with their firm for 8 – 11 years, 64 (18.23%) of the respondents had worked for 4 – 7 years, 46 (13.11%) of the respondents had worked for 1 – 3 years and 70 (19.94%) of the respondents had worked for less than a year.

3.2. Measures

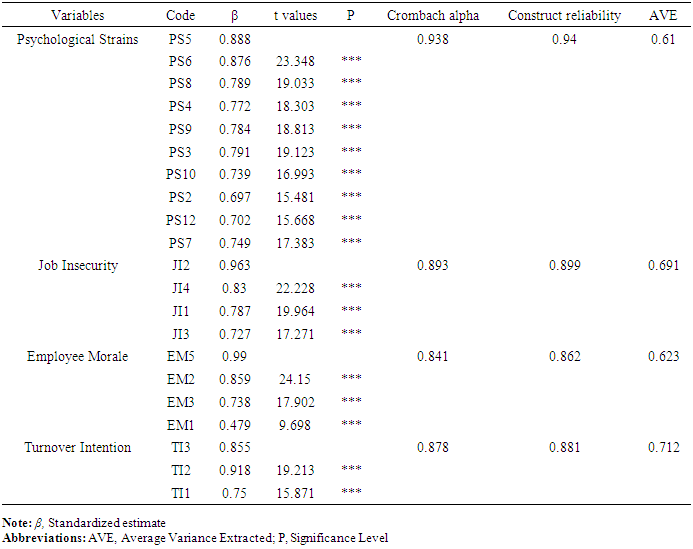

- The questionnaires contained items measuring job insecurity, turnover intention, employee morale, and psychological strain. The research approach adopted for this study was a quantitative one. All conceptual variables were measured with different items from various research work in the literature. Job insecurity was measured with 4 items adopted from De Cuyper, De Witte, Rigotti, and Mohr (2003). A sample item includes “I think I might lose my job in the near future”. The 5 items scales of Employee morale was adopted from the study of Dimitriades and Papalexandris (2011). This scale was originally developed by Young (2000) and contains a sample item such as “Employees take pride in this organization”. The psychological strain was adopted and measured with 13 items developed by Caplan, Cobb, French, Van Harrison, and Pinneau (1980). The Turnover intention was measured with 3 items developed by (Singh, Verbeke, & Rhoads, 1996) with a sample item such as “I often think about quitting”. All the scales were measured on a 6 Likert-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The instruments used passed through psychometric properties checks to ensure that (Green, Dunn, & Hoonhout, 2008) suggestions in selecting scales for similar studies were met. For instance, we checked the reliabilities (e.g. Crombach alpha) and validities (e.g average variance extracted and discriminant validity) of the instruments. The data for the study did not suffer from common method biases since the coefficient of Cronbach alpha value for each of the scales was above the 0.70 threshold proposed by JC Nunnally (1978).

3.3. Data Analysis

- SPSS version 23.0 and AMOS version 21.0 software were employed to analyze the gathered data. The descriptive and inferential statistics were carried out by the use of SPSS. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed for all the 4 variables using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation (eigenvalue > 1 as cut off). Except for four items (thus 1 item from employee morale and 3 items from the psychological strain scales) that loaded inappropriately, the remaining items loaded under their respective components. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) of Sampling Adequacy was 0.881. The variables together explained 70.89% of the total variance at a total eigenvalue of 37.31, hence, indicating that the data did not suffer from common method biases. To further verify the reliability and validity of the scales used in this study, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) in AMOS version 23 software was performed. After performing the CFA (Table 1), the findings showed that each of the items for the survey analysis had a standardized factor loading greater than 0.45 and the t-values were all significant. Cronbach alpha for the data ranges from 0.841 to 0.938 and composite reliability (ranging 0.862 to 0.940) for each of the variables and was greater than the suggested 0.70 threshold by Jum Nunnally (1978) indicating high internal consistency. Also, the average variance extracted (AVE) ranging from 0.610 to 0.712 which was greater than the suggested 0.50 threshold (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair Jr, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2010; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993) was recorded, therefore, indicating high convergent validity. The data had a good model fit with Chi-square (X2) = 580.847, normed chi-square (X2/df) = 3.174, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.051, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.080, and comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.921.

|

4. Results

4.1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation Analysis

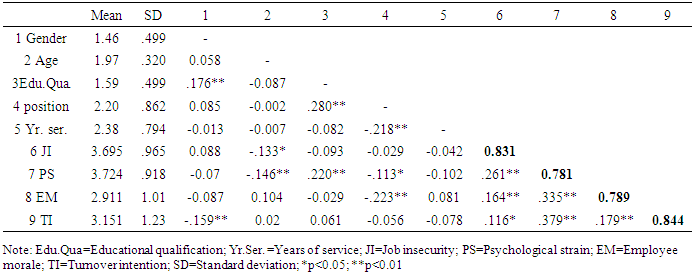

- A Pearson’s correlation analysis was carried out to examine the association among the variables i.e. job insecurity, turnover intention, psychological strain, and employee morale. Likewise, the averages and standard deviations were estimated for the variables. The details are presented in Table 2.

|

4.2. Analysis of the Main and Mediating Effects

4.2.1. Hypotheses Testing

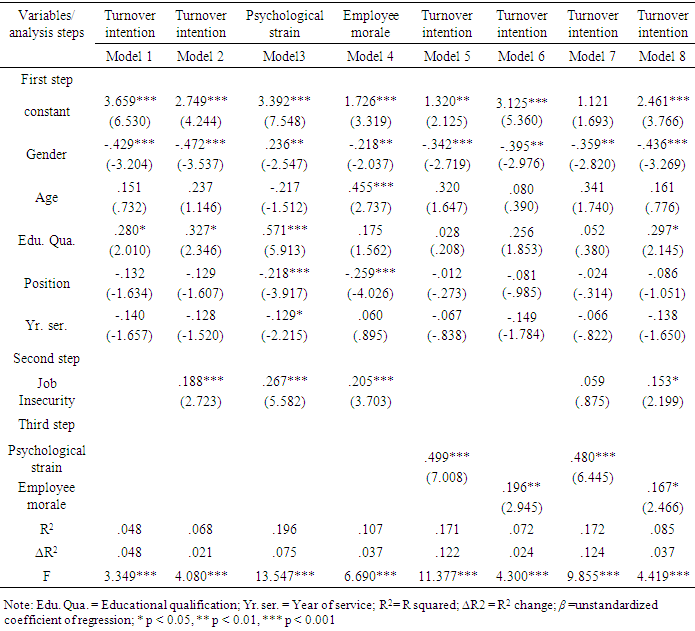

- Controlling for other variables, we analyzed the relationship between variables in this study by using SPSS version 23.0 software to conduct hierarchical regression analysis. The results are presented in Table 3. First, in model 2 in Table 3, the findings suggest that job insecurity had a positive and significant effect on turnover intention (β = .188, p < .001) of savings and loans employees, therefore, providing support for Hypothesis 1. Second, in model 3 in Table 3, when the psychological strain was made the criterion variable, job insecurity positively, and significantly influence psychological strain (β = .267, p < .001), indicating support for Hypothesis 2. Also, in model 5 in Table 3, psychological strain exercised a positive and significant influence on turnover intention (β = .499, p < .001), hence, Hypothesis 3 is supported. Moreover, when job insecurity and the psychological strain was regressed in model 7 in Table 3. The findings show that job insecurity did not affect turnover intention since it was statistically insignificant (β =.059). However, drawing on the proposed mediation analysis assumptions by Baron and Kenny (1986), psychological strain exercised a full mediating effect in the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention (β = .480, p < .001), thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.Similarly, in model 4 in Table 3, job insecurity positively and significantly influenced employee morale (β = .205, p < 0.001) when employee morale was made as a criterion variable, hence, Hypothesis 5 was not supported. Also, making employee morale as the independent variable and turnover intention as the criterion variable, the results in Table 3, Model 6, indicate that employee morale exerted a positive and significant influence on turnover intention (β =.196, p < 0.01), thus Hypothesis 6 is unsupported. Lastly, regressing job insecurity and employee morale in model 8 in Table 3, the results suggest that the influence of job insecurity continued been significantly positive on turnover intention. However, based on the assumptions of Baron and Kenny (1986)] on mediation analysis, there was a partial mediating effect (β =.167, p < 0.05) exercised by employee morale in the job insecurity and turnover intention relationship, and, thus, Hypothesis 7 was supported.

|

5. Discussions

- In this study, a formulated model was tested for which we investigated the influence of job insecurity on turnover intention. Also, two variables (i.e. psychological strain and employee morale) were tested as mediators in the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention. The findings show measures on the job insecurity and turnover intention as the positive relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention corroborated with previous studies (Arijanto et al., 2020; Çınar et al., 2014; Putra & Suana, 2016). On the other hand, we tested the effect of job insecurity on employee’s morale. Arijanto et al. (2020) opine that job insecurity impedes the morale of the employee which led to turnover intention among employees. Also, it is viewed that job insecurity fosters inefficiency and a decline in productivity. Similarly, we tested the impact of job insecurity on the psychological strain and it was found to be positive and significant which is consistent with the following studies (Cheung et al., 2016; Näswall, Sverke, & Hellgren, 2005). This, therefore, extends the present knowledge of job insecurity on the psychological strain. It sheds new light on the relationship between job insecurity and psychological strain by testing the direct effect of job insecurity on psychological strain to predict turnover intention. It revealed that humans are active actors in the cycle of stress. Surprisingly, the positive relationship between job insecurity and the psychological strain was found to increase turnover intention as the relationship strengthens. Again, the assertion that psychological strain positively and significantly influence turnover intention was found to confirm the study of Layne, Hohenshil, and Singh (2004). The direct effect exhibits that it has a more substantial impact on the model interpretation as the extent of psychological strain that Savings and Loans employees report impacted a positive effect on their turnover intentions. Consequently, as strain rises, so will the probability that people will abandon their jobs leading to turnover intention. In the case of psychological strain mediating the positive relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention, the result proved that psychological strain fully mediated the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention. The findings confirmed that the savings and loans employees’ perception of job insecurity directly influences their level of turnover intentions without any mediating mechanism. Consequently, this proves that turnover intention arises among the employees when there is an inception of job insecurity at the workplace irrespective of the psychological strain employees goes through in performing their duties. The implications are that the sources of psychological strain that affects employees job attitudes such as high job demands, job decision latitude, emotional exhaustion, physical and mental health problems, broader spans of control, complex role responsibilities, reductions of resource supports (Wong & Laschinger, 2015), does not cause job insecurity to indirectly affect turnover intention. On the other hand, the hypothesis that job insecurity negatively influences employee morale was not supported. However, it confirms the claims of social exchange theory (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Though in an organization it is unusual for job insecurity to influence employee morale positively since it dampens the morale of employees, conversely, it was revealed that situations of this kind sometimes happens when achievement of work targets determines the probability of an employee to maintain his/her job in the company. The insecurity exercised by the employees fosters their morale towards their goal attainment and is the reality in many Savings and Loans organizations. Besides, it was validated that optimistic employees do achieve high set work targets even though it is a negative influence on their work activities. This promulgates high morale among them. Moreover, the hypothesis that employee morale negatively influences turnover intention was not supported since employees with affective commitment, irrespective of the insecurity employees perceive, possess high morale limiting their intent to leave the organization. Intuitively, it was discovered that most of the employees are affectively committed to their companies and imbibe in them a certain level of satisfaction making turnover unattractive. Moreover, employees sometimes decline to leave considering the enormous work experience acquired for some time with the organization. Leaving the organization for another may come with learning new skills to cope with the new environment and challenges. However, when morale is low as a result of employees not affectively committed would promote their intention to leave. Again, employee morale exerted a partial mediation in the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention. This implies that job insecurity affects turnover intention through the level of employee morale. Also, the high and low morale perceived by employees through the activities of employee’s behaviors such as affective commitment and job satisfaction directly or indirectly contributed to turnover intention.

5.1. Implications of the Study

- It is established by Çınar et al. (2014) that there are factors that cause job insecurity positive effect on turnover intention. First, job insecurity is promoted by a lack of communication by management on future dealings. This happens when there is no effective rapport between management and employees. When there is open communication about future events it curtails the insecurity. Open, honest, and prompt communication harness the probability and controllability of events bounds to happen in the future. When communication evolves in such a manner it establishes employee feelings of belongingness. Second, participative decision-making reduces insecurity among employees. When employees become more abreast of the current situation in the organization by involving them in decision-making, it makes them feel part of the organization and improve their motivation level leading to their intent to stay.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The current study tested a model of research that observes two constructs as mediators between job insecurity and turnover intention. The results show that the existence of job insecurity occasioned turnover intention. Also, job insecurity positively and significantly predicted psychological strain. Besides, job insecurity resulted in positively predicting employee morale. Similarly, the incidence of employee morale reduced the employees’ turnover intention. Theoretically, employee morale partially mediated the job insecurity and turnover intention relationship whereas psychological strain fully mediated the relation between job insecurity and turnover intention. Furthermore, based on the fallouts, we conclude that employees experiencing high morale based on the level of job satisfaction and affective commitment keep on staying with the organization rather than leaving and this reduces turnover intention of employees. Based on the aforementioned empirical outcomes, we recommend the management of Savings and Loan companies to institute policies that exterminate high role demands that come with set targets of which when employees are unable to achieve they are shown the exit. Again, policies that usher employees into the feeling of insecurity about the future of their job should not be entertained. Furthermore, a workplace environment that would institute the hope that employees can keep their job should be adhered to which promotes high morale to possibly reduce the rate of turnover intention in their organization. Moreover, management should mitigate the factors that are persistent in the organization which promotes psychological strain.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are very grateful to Mrs. Patricia Eshun of Lower-Pra Rural Bank and Ms. Felicity Atta-Araba Obeng of Guarantee Trust Bank for their assistance in the data collection. Also, we are thankful to Mrs. Victoria Asante for an immense contribution to the writing skill of this paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML