-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2019; 9(1): 25-36

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20190901.03

Fostering Client Orientation for Effective Organizational Performance

Jean Bosco Nzitunga

Administration and Operations, International Criminal Court (ICC), Bangui Field Office, Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR)

Correspondence to: Jean Bosco Nzitunga, Administration and Operations, International Criminal Court (ICC), Bangui Field Office, Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR).

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Two essential aspects emphasized by the current Namibian government and new sustainable development goals (SDGs) are poverty alleviation/eradication and equality of access to national economy. For the achievement of these objectives, strategic development of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) will play a crucial role in this regard. While a number of scholars have focused their interest on studying and understanding the determinants of organizational performance in SMEs, little research has been conducted in this regard in the context of Namibian small accommodation/hospitality enterprises (also referred to as Guest-houses). A careful investigation revealed a dearth of literature in this regard, which led to the following research question: “what is the influence of client orientation and learning orientation on guest-houses’ performance in Namibia?” An experimental quantitative research design was used to answer the above question. The population for this study comprised employees from 20 top-ranked guest-houses in Windhoek. These 20 guest-houses have a combined total of 112 employees (including managers) and a 6-point Likert scale questionnaire was administered to all of them. The response rate was 89%. To analyse the collected data, descriptive statistics and inferential statistics (Partial Least Squares regression analysis) were used. The results revealed a positive influence of client orientation and learning orientation on guest-houses’ performance in Namibia.

Keywords: Client orientation, Learning orientation, Guest-houses, Performance

Cite this paper: Jean Bosco Nzitunga, Fostering Client Orientation for Effective Organizational Performance, Management, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 25-36. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20190901.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- A critical challenge confronted by today's organizations is client orientation, and to gain their clients’ satisfaction which enables the organization to survive in the world of competition (Jeong, Kim, & Yoon, 2014, p.36). Client orientation, an important issue generally for all firms and particularly for service providing firms, is a conception which places customers in the focus as one of the most important organization’s stakeholders (Kim, Young-Gul, and Chan-Wook, 2010, p.315).In order to survive in the contemporary turbulent, unstable and globalized marketplace, hotels need to ensure a sustained competitive advantage. According to Tajeddini (2010, p.221) hotels need to place client orientation at the heart of the hotel’s competitiveness. Complementing this suggestion, Roxana, Anamaria, and Corina (2013, p.808) note that a key component in the success of hotels is the extent of their innovativeness. Current research has revealed that service firms, like hotels, require a better understanding of client orientation and its great importance to such firms and their performance (Mohammed and Rashid, 2012, Iorgulescu and Rãvar, 2013). As in the service-oriented organization, the delivery of service in a hotel occurs when there is interaction between service providers and the service encounter (alem Mohammad, bin Rashid, and bin Tahir, 2013, p.229). Hence in order to enhance service experience, hoteliers need to focus on client interaction. Client orientation can be achieved through a positive relationship between client and service provider. Research supports the notion that client orientation leads to increased organizational performance (Asikhia, 2010; Kim et al., 2010). Furthermore, client orientation is also one of the market beneficial sources, it helps organization to understand client, and hence resulting in enhanced client satisfaction (Roxana et al., 2013, p.809).Here, it is important to note that the main purpose behind client -oriented behaviours is to increase client long-lasting satisfaction and to create client-loyalty. Therefore, good client-oriented behaviours, in an organization, definitely ensures a tremendously positive impact on its performance (Maurya, Mishra, Anand, and Kumar, 2015, p.161). Client-oriented behaviours can maintain a good relationship between the service provider and the clients, leading to improvement in the organization’s performance (Kasemsap, 2016, p.117). One of the important purposes of client-oriented behaviours is to increase long-term satisfaction and to create client loyalty. Studies have demonstrated that stronger client-oriented behaviours in organizations have a positive impact on the organizations’ performance (Frambach, Fiss, Ingenbleek, 2016; Kim et al., 2010). This suggests that managers need to adopt a client-centred strategy, implying a modification and adjustment of cultural norms, organizational structure, and employee performance measures and rewards (Jeong et al., 2014, p.37). When employees of client-oriented hotels provide a superior service, the service image of the hotel will improve, and will have a direct relationship with process fit after system implementation (Fan and Ku, 2010, p.206).In Namibia, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are recognized as catalysts in the socio-economic development of the country. They are considered as veritable vehicles for the achievement of macro-economic objectives in terms of employment generation at low investment cost and the development of entrepreneurial capabilities, indigenous technology, stemming rural-urban migration, local resource utilization and poverty alleviation. However, as a result of a web of interconnected aspects – including the current economic downturn – SMEs are experiencing competitive pressure. In this hostile trade atmosphere, SMEs need to ensure a sustained enhancement of their client orientation and organizational performance (Nzitunga, 2015, p.117). For the past 2 years, Namibian guest-houses have experienced sustained client turnover which is mainly resulting from the current economic downturn, competition from bigger hotels, and lack of appropriate strategies for client orientation and learning orientation. Increasing client acquisition costs and growing client expectations are making the guest-houses’ performance and competitiveness depend considerably on their ability to satisfy clients efficiently and effectively (Adam, Stalcup, and Lee, 2010, p.140). These challenges are compounded by the lack research in this sector. While several scholars have identified client orientation as key determinant of organizational performance (Nasution et al., 2011; Tajeddini and Trueman, 2012; Leekpai and Jaroenwisan, 2013), there is a dearth of literature in this regard in the Namibian guest-house context. The implication of this is that, in this sector, the link that is thought to be existent between these aspects is rather assumed than proven empirically.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualization of Client/Customer Orientation

- Asikhia (2010, p.198) defines client/customer orientation as a concept which transforms marketing into a potent competitive weapon, shifting organizational values, beliefs, assumptions, and premises towards a two-way relationship between clients and the firm. On their part, Maurya et al. (2015, p.162) note that client orientation is the sufficient understanding of one’s target buyers to be able to create superior value for them continuously. Client oriented culture suggests that an organisation concentrates on providing products and services that meet client needs (Iorgulescu and Rãvar, 2013; Fan and Ku, 2010). Early on, Saxe and Weitz (1982) conceptualized client orientation as a practice of the marketing concept, however it fails to elucidate if it is a philosophy or a strategy at the individual level. On their part, Wachner, Plouffe and Grégoire (2009, p.34) conceptualized client orientation as characteristics of salespersons’ which would help in understanding variance in sales outcomes. Singh & Koshy (2012, p.70) derived six domain areas of the salesperson’s client orientation construct which integrated salesperson’s client orientation, marketing concept, and other related interpersonal behavioural constructs. Based on their analysis they defined client orientation as “client-centric behaviours, which include gathering and disseminating information relevant for clients, to understand and continuously fulfil their hierarchy of latent needs, and to keep them satisfied by creating and delivering value through long-term relationships.”The highly influential early proponents of client orientation, Drucker (1954) and Levitt (1960) both viewed client orientation as a top priority for management, but at the same time they saw that it was too important and all-penetrating to be left as the responsibility of management and marketing functions alone. Rather, client orientation is the whole business as seen from the client’s point of view, an aspiration of the whole organization. This is the view supported by many present marketing scholars as well (Gummesson, Kuusela, and Närvänen, 2014). However, the idea that an organisation should define itself in terms of client needs has not been accepted by all. Ansoff (1965) especially summoned early on that it is not enough for a company to focus on clients but that it also should define its strategy based on technical competencies and its own ability to respond to client demand. The original idea of client orientation turned to market orientation and merged with strategic planning and management (Webster Jr, 1988). Management attention shifted away from clients with the perspective of strategic planning although it is in no way inconsistent with client orientation. Moreover, the difficulty of dealing with constant change implicit in client orientation and the emphasis on client orientation systems and short-term performance added to the shift in attention (Webster Jr, 1988). As the concepts of client orientation and market orientation have changed multiple times over history, it is very difficult to make a clear distinction between them. This closeness of the terms can be noticed, for example, in Shapiro (1988, p.120) who states that “I've also found no meaningful difference between ‘market driven’ and ‘client oriented’, so I use the phrases interchangeably.” On the other hand, Narver & Slater (1990) make a clear distinction between the two terms, but even for them client orientation is the focal component of market orientation that is seen as consisting of client orientation, competitor orientation and inter-functional coordination. When such a distinction is made, many researchers still consider client orientation to be the most fundamental aspect of market orientation (Heiens, 2000). In the words of Gummesson (2008, p.316), “both in literature and practice the concepts of client and marketing orientation are mixed up. Marketing orientation is broader, not only including clients but also competitors and how markets function.” As can be seen, different authors have somewhat different definitions for client orientation and market orientation; even today no shared definitions exist of these elusive concepts. Yet, the definitions of both concepts by a wide range of influential authors (Shapiro, 1988; Kohli & Jaworski, 1990; Narver & Slater, 1990; Deshpandé, Farley, and Webster Jr, 1993) include similar core content of organization wide focus on client value. The same concept of client orientation is also often expressed using the terms client focus (Weerawardena and O'Cass, 2004; Gulati & Oldroyd, 2005) or client centricity (Kumar, Scheer, and Kotler, 2006; Gebauer, Gustafsson, and Witell, 2011).In the contemporary trade environment, client orientation means “collaborating with and learning from clients and being adaptive to their individual and dynamic needs. A service-centred dominant logic implies that value is defined by and co-created with the consumer rather than embedded in the output” (Vargo & Lusch, 2004, p.6). Furthermore, outcomes (e.g. financial) are not something to be maximized but something to learn from as firms try to serve their clients better and improve their performance.

2.2.1. Client Orientation in the Contemporary Trade Environment

- Frambach, Fiss, and Ingenbleek (2016, p.1429) argue that contemporary client orientation requires a continuous positive disposition towards meeting clients’ exigencies and therefore a high degree of concern for these clients. What is interesting is the suggestion by Jeong, Kim, and Yoon (2014, p.38) that client-oriented culture is nurtured through regular supply of client information about their needs so as to be able to design and deliver good products. This view is also supported by Adam, Stalcup, and Lee (2010, p.141) who further posit that client orientation as a component of market orientation has its fundamental thrust in pursuit of putting clients at the centre of strategic focus. Elaborating on this same proposition, Jeong et al. (2014, p.39) stress that client-oriented culture involves excellence in client interactions, market and client familiarity and an emphasis on cooperation.Mazreku (2015) advanced a framework for auditing a client orientation profile, which achieves definition, sensibility, measurement, and implementation. In the view of Mazreku (2015, p.30), client orientation refers to a process of putting clients at the heart of an organization that is, having the appropriate vision of clients and their needs; a phenomenon that makes the organization to see itself through the eyes of the clients.A client-oriented behaviour is the ability of the service provider to help consumers, which leads not only to an increase in client satisfaction and a positive relationship with employee performance (Leekpai and Jaroenwisan, 2013, p.168) but also a level of emotional commitment to the organization of these consumers, and more importantly, for retaining these consumers, especially in the case of services with high interaction, as seen in the hotel industry. Research has shown that client orientation has positive effects on sales performance, quality perception by the consumer, and construction of buyer-seller relationships and client satisfaction. This is an essential factor for success in organizations in the service sector (Mohammed and Rashid, 2012, p.222). This is also echoed by Tajeddini and Trueman (2012, p.1121) who maintain that client orientation focuses primarily on the realization of the interests and needs of clients and deliver appropriate solutions to their requests. Nevertheless, Ali, Leifu, and Rehman (2016, p.3) caution that in an environment of high contact as the hotel industry, the physical evidence (tangible) gives strong clues as to the quality of the service provider to communicate a message to the client about the establishment before and during the meeting, and strongly influences assessing the overall experience. But for Brunner-Sperdin, Peters, and Strobl (2012, p.24), in addition to the service environment, the role of human factors in providing high quality service has been widely recognized in the literature. Employees who are in direct contact with consumers are able to substantially affect the perception of clients in service environments. Thus, client satisfaction, loyalty or evasive behaviour is strongly influenced both by the appearance of frontline employees as their competence and behaviour. Elaborating on this proposition, Naseem Ejaz, and Malik (2011, p.53) point out that, although it is essential to anticipate the needs of clients in each phase of service, it is also important to meet their expectations. Moreover, the quality of service provided by attendants, their techniques for dealing with clients and flexibility influence the feeling of gratification by clients.Many studies provided evidence that being client-oriented leads to obtaining a competitive advantage and high performance. In order to obtain these goals, hotel management have to consider client orientation like a key element of current decision-making process. In the hotel industry context, Al-Ababneh (2016, p.191) views client orientation as the degree to which the hotel obtains and uses information from clients, develops a strategy which will meet client needs, and implements that strategy by being responsive to clients’ needs and wants. Thus, a hotel should be able to answer and deeply analyse the following question: “What exactly do tourists want and value?” The first step a hotel must take to find the answer is to closely monitor its tourists. A large number of studies have focused on Front-Office employees from hotels (Tajeddini, 2010, p.222) like a primary resource through which hotels can gain a competitive advantage. In the words of Sohrabi, Vanani, Tahmasebipur, and Fazli (2012, p.98), “employees should have the following characteristics: ability to clearly identify and focus on relevant information and objectives, to develop appropriate and/or new solutions to certain types of problems, active listening and interacting with tourists, task orientation, responsibility, feedback oriented, organizational commitment and flexibility.” In support of this proposition, Naseem et al. (2011, p.54) caution that developing a sufficient understanding of tourists in order to deliver attractive, personalized and competitive hotel services is not enough. Hotel management must understand that, tourists’ needs, expectations and perceptions of services’ benefits change over time. Therefore, hotel management has to systematically and continuously adjust the hotel offerings in order to deliver a memorable experience, not a simple hotel service. Thus, the client orientation is considered an important tool for achieving high performance in hotels, whether client orientation is viewed from the perspective of product or service delivery (Tajeddini, 2010, p.222). What is interesting is the submission by Brunner-Sperdin et al. (2012, p.25) that many organizations have well-developed planning processes but the extent to which client goals are included, implemented, and monitored is inadequate. In light of this view, Sohrabi et al. (2012, p.104) recommends that the mission of the organization as far as the clients are concerned must be well articulated; present performance level in this regard must be ascertained. Any vacuum between the organizational desires and actual achievement must be outlined. Operational measures are seen to stimulate a more focused and integrated organizational effort, and provide a benchmark for determining whether client orientation strategies are working as intended (Sohrabi et al., 2012, p.105). Measurements can be carried out through formal and informal techniques. The formal techniques use client-based quality performance measures to gauge true perception as well as subconscious factors which impel client behaviour, while informal measurement evolves where there is no set standard. In this case, rule of thumb is applied (Kasemsap, 2016, p.118). A number of researchers have examined the link between client orientation and performance. Client orientation is significantly important in enabling firms to understand the market place and develop appropriate product and service strategies to meet client needs and requirements (Maurya, Mishra, Anand, and Kumar, 2015, p.163), which translate into performance. For Ali et al. (2016, p.5), the development and implementation of client orientation is an impetus for organizational positioning in the market place. This position is supported by an array of studies that confirm significant associations between client orientation of an organisation and its overall performance (Nasution, Mavondo, Matanda, and Ndubisi, 2011; Tajeddini and Trueman, 2012; Leekpai and Jaroenwisan, 2013). According to Serna et al. (2016, p.36), once a hotel becomes client-oriented, it begins to adopt and implement a learning orientation. Therefore, the relationship between client orientation and organizational performance cannot be analysed in isolation without taking into account the role of learning orientation in this regard, which is discussed in the next section.

2.2. Learning Orientation

- Nasution et al. (2011, p.338) conceptualize learning orientation as consisting of commitment to learning, shared vision and open-mindedness. For Martinette and Obenchain-Leeson (2012, p.44), learning orientation refers to those firm values that influence an organisation’s approach to acquiring information. Here, the emphasis is put on the importance of planned processes in allowing firm learning to lead to the achievement of common organisational goals. Other scholars take a strict approach and claim that for meaningful learning to occur, learning must result in a behavioural change (Serna et al., 2016; Lord, 2012). In contrast, Preziosi, McLaughlin, and McLaughlin (2011, p.10) argue that the new knowledge a company acquires will create the potential for the firm’s values to influence its behaviour. Thus, they do not require an actual change in behaviour. In this study, a learning organisation is defined as an organisation with a learning orientation. Based on Martinette and Obenchain-Leeson (2012, p.44), this study defines an organisation with a learning orientation as an organisation that creates and uses knowledge to obtain a competitive advantage, especially if the process involves strategic planning and is executed across the whole organisation. Furthermore, in accordance with Martinette and Obenchain-Leeson (2012), the term learning orientation is defined as an organisation’s commitment to learning, shared vision, open-mindedness and intra-organisational knowledge sharing. A learning orientation helps an organisation to acquire, disseminate and share information (Nasution et al., 2011, p.339). On their part, Hussein, Mohamad, Noordin, and Ishak (2014, p.301) argue that organisations focused on learning can achieve a better understanding of the organisational factors that affect the acquisition of new knowledge related to technology and the market. An organisation’s learning orientation will help the firm to use information from its clients to improve its products and services, increase its sales and maintain a larger client base. The learning orientation can also increase the firm’s knowledge base and enable it to utilise its resources more effectively (Hussein et al., 2014, p.299). For example, in traditional manufacturing firms, knowledge about raw materials and technical knowledge about machinery can be critical to performance. An organisation’s ability to acquire and apply this knowledge to its operations is a cornerstone of its learning orientation (Preziosi et al., 2011, p.11). A larger knowledge base achieved through continuous learning processes will also render the firm a more attractive collaborator to its competitors, suppliers and clients. For example, a supplier of sawmill and wood is attractive if it has a high degree of fundamental knowledge about how to use wood. Furthermore, for an organisation to improve its performance over time, the firm must learn to understand and satisfy its clients’ demands (Dekoulou and Trivellas, 2014, p.350). Additionally, an organisation with a learning orientation will typically monitor its competitors’ behaviours in the market (Akhtar, Arif, Rubi, and Naveed, 2011, p.21) to understand and learn from their strengths and weaknesses (Dekoulou and Trivellas, 2014, p.351).Firms with a learning orientation can achieve higher levels of strategic capability (Hussein et al., 2014, p.301), which allows them to build long-lasting competitive advantages (Martinette and Obenchain-Leeson, 2012, p.45). Such firms tend to be more perceptive and better at coping with significant environmental changes (Akhtar et al., 2011, p.24). However, the learning orientation must be implemented properly. For Sanni (2016, p.29), although the knowledge shared among employees can result in a learning orientation (and thus in a higher financial performance), errors can occur during the knowledge-sharing process, with negative consequences for an organisation’s overall performance.Learning orientation is reflected in increased efforts by the employee to actively expand his or her existing repertoire of technical and social skills, thus learning new and better ways of interaction with clients (Preziosi et al., 2011, p.12). Therefore, learning orientation is considered one of the most valuable resources, allowing guest-houses to address issues such as globalization and economic uncertainty. Many studies found that learning orientation has a direct and positive effect on organizational performance (Dekoulou and Trivellas, 2014, p.353). Nasution et al. (2011, p.340) concur and underscore that commitment to learning necessitates top management support, training initiatives, and the payment to those who translate their learning into superior performance. Basically, workers must be encouraged to challenge the status quo, to develop new ideas, innovate, and continuously evaluate their activities with a view to improving performance. The relation between learning orientation and organizational performance was the interest of many scholars. In this context, several studies declare a positive effect of learning orientation on organisational performance (Nasution et al., 2011; Preziosi et al., 2011, Dekoulou and Trivellas, 2014; Martinette and Obenchain-Leeson, 2012; Akhtar et al., 2011).

2.3. Organizational Performance

- According to Jenatabadi (2015, p.3) organizational performance can be generally defined as “a set of financial and nonfinancial indicators which offer information on the degree of achievement of objectives and results.” Cocca and Alberti (2010, p.192) suggest that organizational performance can be represented by the following dimensions: effectiveness, efficiency, quality, productivity, quality of life, profitability, innovation and learning. Effectiveness refers to the organization’s ability to accomplish its goals in right way while efficiency refers adequate use of resources to accomplish determined goals. Quality refers to the ability to effectively to meet or exceed client expectations (Field, 2011, p.275); productivity is concerned with the ratio of output over input; quality of work life denotes the affective response of employees about their work and organization (Pavlov and Bournce, 2011, p.103); profitability refers to the excess revenues over costs while innovation refers to continuous improvement of product/service or processes (Rhee, Park, and Lee, 2010, p.66); and according to Argote (2011), “learning has been defined as the ability of an organization to continuously create, retain and transfer knowledge within an organization.” Key dimensions of organizational performance identified by other scholars include the ability to innovative productivity; employee satisfaction and amplified capability to gain, transfer and make use of new knowledge; competitive advantage; and enhancement of the organization’s reputation (Liao and Wu, 2010; Rhee et al., 2010, Field, 2011).For guest-houses in Namibia, organizational performance refers to the guest-house’s effectiveness and efficiency in (i) setting standards, specifications, objectives, and goals and achieving them, and (ii) ensuring satisfaction of clients and all other relevant stakeholders. For this to be achieved, it is imperative to ensure sustained client orientation and learning orientation.

2.4. Client Orientation and Organizational Performance

- Evidence for a positive effect of client orientation on organizational performance was found by several early researchers. Swenson and Herche (1994) studied the selling behaviours of the industrial salespeople and found that client-oriented selling behaviours were positively related to organizational performance. Similar results were later found by Wachner, Plouffe, and Grégoire (2009) who analysed the impact of client orientation on sales performance and found a positive effect in this regard. Also, the study by Harris, Mowen, J. C., and Brown (2005) revealed that salespeople who have a stronger client orientation tend to achieve higher levels of sales performance.Recently, a study by Schwepker and Good (2013) indicated a positive relation between client-oriented selling on both outcome performance and behaviour sales performance. The study found that the higher the sales person’s client orientation the greater the sales performance. The study concluded that a strategic perspective of the sales person to assist clients through understanding their needs and assisting clients reach their objectives can expect these efforts to result in returns that will benefit their own sales-related performance.In their study on the effect of client relationships management on citizens’ satisfaction in Mashhad Municipal Regions in Iran, with an emphasis on client orientation as one of the key constructs of client relationships management, Mohsenian, Khorakian, and Maharati (2014) found a strong positive influence of client orientation on citizens’ satisfaction. The study used structural equations modelling and the Least Partial Squares to analyse the data. The sample comprised 182 municipality employees and 265 referees to Mashhad municipality. The other selected construct for client relationship management, namely innovation, did not have an influence on citizens’ satisfaction. Abdul Alem, Basri, and Shaharuddin (2013) analysed the effect of client relationship management (CRM) on organizational performance dimensions in Malaysian hospitality industry. The goal of their research was to investigate the correlation between CRM dimensions, e.g. CRM and client orientation, knowledge management and technology-based CRM, and various aspects of organizational performance e.g. financial, client, internal processes, training and growth in Malaysian hotels. The research was a quantitative study of 152 Malaysian hotel managers of hotels ranging from 3-star to 5-star. The findings of the study indicated a positive influence of all the CRM constructs on hotel performance, with the relationship between client orientation and hotel performance being the strongest.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

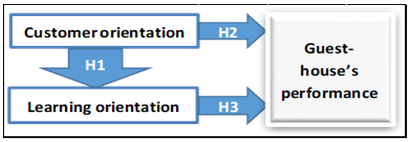

- This study used an experimental quantitative design. In an experimental design, “the researcher actively tries to change the situation, circumstances, or experience of participants, which may lead to a change in behaviour or outcomes for the participants of the study” (Bhattacherjee, 2012, p.8). The researcher randomly assigns participants to different conditions, measures the variables of interest and tries to control for confounding variables. Based on the research problem and the literature reviewed in Section 2, this study seeks to enrich the body of knowledge in the area of client orientation and organizational performance by advancing and analysing a model which postulates client orientation and organizational learning orientation as determinants of organizational performance. Figure 3.1 presents the research model.

| Figure 3.1. Research Model (adapted from Nzitunga, 2015) |

4. Methodology

- This was a quantitative study. Based on the literature, a 6-point Likert scale questionnaire was developed to assess the different variables of the research model as it is one of the best instruments recommended for a quantitative study (Bhattacherjee, 2012). It was imperative that the questions fitted the respondents' frame of reference. In this regard, it was necessary to ensure that respondents would have enough information or expertise to answer the questions truthfully. The population for this study comprised employees from 20 top-ranked guest-houses in Windhoek. These 20 guest-houses have a combined total of 112 employees (including managers) and the questionnaire was administered to all of them, using stratified sampling to ensure sampling error reduction (Singleton and Straits, 2010). The response rate was 89%.

4.1. Validity and Reliability

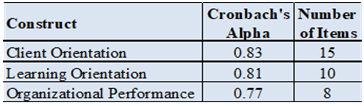

- For this study, face validity was ensured through the use of previously validated measures (Asikhia, 2010; Martinette and Obenchain-Leeson, 2012; Jenatabadi, 2015), which were refined where necessary. According to Waters (2011, p.38), face validity is established when the measurement items are conceptually consistent with the definition of a variable, and this type of validity has to be established prior to any theoretical testing. The reliability of variables in the research instruments is only confirmed by their clear ability to produce stable responses over several measurements of the instrument surveys (David, Patrick, Philip, & Kent, 2010, p.24). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess the internal consistency-reliability of the scale used. Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of internal reliability for multi-item summated rating scales, and its values range between 0 and 1, where the higher the score, the more reliable the scale (Waters, 2011, p.40). Satisfactory reliability is indicated by alpha score values of above 0.70 across all sections of the measuring instrument (Cooper and Schindler, 2011). The scores summarized in Table 4.1 below show that the scale utilized was reliable.

|

5. Findings and Discussion of Results

- The descriptive statistics included means and standard deviations to describe the different variables in this study. Spearman correlations were used to determine the relationships between the different variables, as the collected data were ordinal. Finally, Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression was used to test the multivariate relationships hypothesised by the research model.

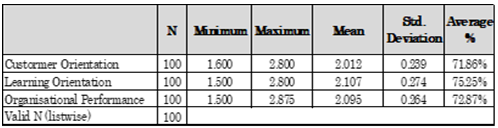

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

- According to van Elst (2015, p.5), descriptive statistics are used to describe the characteristics of the respondents through the use of frequencies, means, modes, medians, standard deviations, and the coefficient of variation to summarise the characteristics of large sets of data. To do this, a composite score was obtained for each variable by totalling the individual scores of the relevant items and calculating the average. Descriptive statistics of the composite variables are summarized in Table 5.1.

|

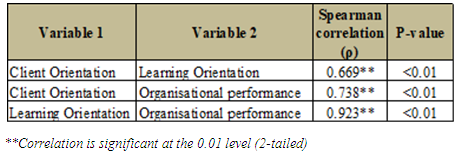

5.2. Correlations

- According to Rebekić, Lončarić, Petrović, and Marić (2015, p.49), correlation analysis refers to the degree to which changes in one variable are associated with changes in another. It seeks to establish the potential existence of a linear connection between variables. Two types of correlations - namely the Pearson product moment correlation and Spearman correlation coefficient - are generally used. For interval or ratio scales, the Pearson correlation is used while the Spearman correlation is used for ordinal data (Rebekić et al., 2015, p.49), and it was used in this study. Table 5.2 summarises the Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) and p-values for the different variables.Table 5.2 shows strong statistically significant positive correlation between client orientation and learning orientation (ρ = 0.669); client orientation and organisational performance (ρ = 0.738); and learning orientation and organisational performance (ρ = 0.923).

|

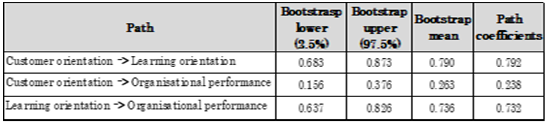

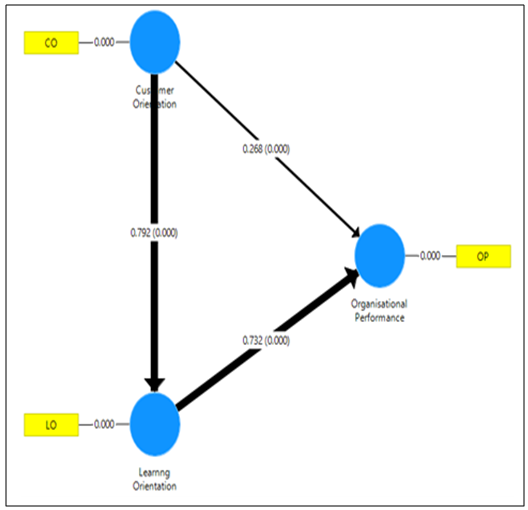

5.3. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression Analysis

- Grounded on Abdi & Williams (2013) who recommend this method as the most suitable method to analyse multivariate relationships, Partial Least Squares regression analysis was used as inferential statistics. Another advantage of PLS regression is the fact that it does not necessitate a vast sample or data which is normally distributed (Abdi & Williams, 2013, p.568). In a PLS model, the significance of the paths and path coefficients is assessed using the bootstrap confidence intervals. The bootstrap confidence intervals for this study are presented in Table 5.3 below.

|

| Figure 5.1. Path, strength and significance of the path coefficients assessed by PLS (n=100) |

5.4. Summary of Key Findings

5.4.1. Influence of Client Orientation on Learning Orientation

- Consistent with the literature reviewed in Section 2, the first hypothesis that client orientation is likely to positively influence guest-houses’ learning orientation in Namibia, was confirmed by strong statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.792). This implies that ensuring employees’ belief that the client is the most important thing; devotion of maximum attention and effort to providing the highest levels of client service; feeling of a personal sense of achievement when clients are delighted; understanding and anticipation of client needs and working tirelessly to meet them; willingness to go above and beyond the call of duty to help clients and resolve their problems; thriving on ensuring that the client experience is the best it could be; seeing client complaints firstly as opportunities to create client satisfaction; and drive to make sure that every client feels valued, will lead to their enhanced learning orientation.

5.4.2. Influence of Client Orientation on Guest-houses’ Performance

- The second hypothesis, namely that there is a positive relationship between client orientation and guest-houses’ performance in Namibia, was confirmed by statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.268). These results are consistent with the literature reviewed in Section 2. Managerial implications are that ensuring employees’ belief that the client is the most important thing; devotion of maximum attention and effort to providing the highest levels of client service; feeling of a personal sense of achievement when clients are delighted; understanding and anticipation of client needs and working tirelessly to meet them; willingness to go above and beyond the call of duty to help clients and resolve their problems; thriving on ensuring that the client experience is the best it could be; seeing client complaints firstly as opportunities to create client satisfaction; and drive to make sure that every client feels valued, will greatly contribute to enhanced guest-houses’ performance.

5.4.3. Influence of Learning Orientation on Organisational Performance

- The third hypothesis, which posited that positive relationship exists between learning orientation and guest-houses’ performance in Namibia, was also evidenced by strong statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.732). Again, these findings are consistent with the literature reviewed in Section 2 of this paper. Ensuring adequate consideration of learning ability as the key to competitive advantage; consideration of employee learning as an investment, not an expense; perception of learning as a key determinant of organisational survival; emphasis on the importance of knowledge-sharing; and rewarding employees for learning will boost organisational performance.

6. Summary

- Given the dearth of the literature in this field in the context of Namibian small accommodation/hospitality enterprises, this study has contributed to supplementing the client orientation and learning literature. The findings of the study revealed low scores for client orientation, learning orientation, and guest-houses’ performance, which points to the need for urgent improvement in this regard. Sufficient evidence emerged from the study showing that it is imperative to ensure adequate client orientation and learning orientation for improved guest-houses’ performance. These aspects are measurable, and therefore can be managed. Guest-house managers need to effectively address these issued and will require unrelenting support from researchers and other relevant stakeholders.

7. Conclusions

- Given the findings of the study which revealed unsatisfactory levels of client orientation, learning orientation, and guest-houses’ performance, as well as a significant positive influence of client orientation and learning orientation on guest-houses’ performance, guest-house managers should ensure that effective strategic planning is incorporated into all stages of client relationship management, and learning orientation, and ensure that performance is objectively measured. The general research framework formulated for this study will guide further research, re-appraise current practices and provide basic guidelines for new policies. As only guest-houses operating in Windhoek, the results of this study cannot be generalised to this entire hospitality industry in and/or outside Namibia. Future research should cover other regions and stakeholders such as the customers themselves.

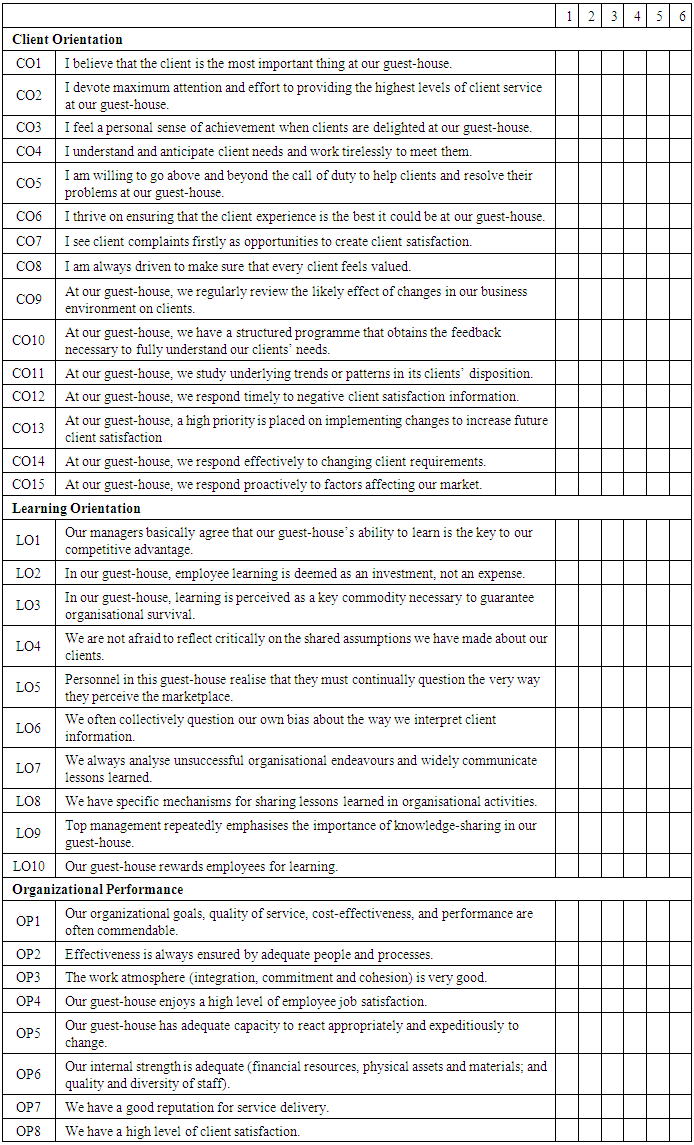

Appendix 1: Research Questionnaire

- Exploring the Influence of Client Orientation on Organizational Performance: The Case of Small Accommodation Enterprises’ Performance in Namibia.The aim of this research is to deepen the body of knowledge in the area of client orientation by gauging its impact on organizational performance in small accommodation/hospitality enterprises and - in so doing – serve as a guiding instrument for guest-house managers for the development of enhanced client orientation and learning mechanisms which would then lead to improved organizational performance. Your responses will be treated as confidential and the information will not be used for commercial purposes.For each of the statements below, please rate your answer and mark with (x) the appropriate box as follows:Strongly disagree (1); Disagree (2); Disagree moderately (3); Agree moderately (4); Agree (5); and Strongly agree (6).There are no “right or wrong” answers to these questions; so please be as honest and thoughtful as possible in your responses. All responses will be kept strictly confidential.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML