-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2018; 8(1): 28-34

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20180801.05

The Role of Individual Factors as a Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intention: Case of Female University Students

Omar Belkheir Djaoued1, Benachenhou Sidi Mohammed2, Arzi Fethi1

1Faculty of Economic Sciences, Dr. Moulay Tahar University, Saida, Algeria

2Faculty of Economic Sciences, Abou Bekr Belkaid University, Tlemcen, Algeria

Correspondence to: Benachenhou Sidi Mohammed, Faculty of Economic Sciences, Abou Bekr Belkaid University, Tlemcen, Algeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This article attempts to explain the formation of the entrepreneurial intent of female university students who benefit from programs and training courses in various fields of the economy. The main objective of our study is to describe and anticipate individual variables (such as personality, motivation, risk-taking and attitude) on the students' entrepreneurial intentions. The study was conducted among 120 students in various fields of economics and management at Tlemcen University. The results showed that the model of intention used can be useful in predicting the intentions of the establishment of the organization because the hypotheses of the research were all confirmed. The other main result that emerged from this study was the mediation effect of students’ attitudes on the effects of individuals’ factors on the path to entrepreneurial intentions.

Keywords: Female Entrepreneurship, Personality, Motivation, Risk-taking, Attitude and Entrepreneurial intention

Cite this paper: Omar Belkheir Djaoued, Benachenhou Sidi Mohammed, Arzi Fethi, The Role of Individual Factors as a Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intention: Case of Female University Students, Management, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2018, pp. 28-34. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20180801.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In recent decades, researchers and policymakers in developed and developing countries have increasingly focused on the role that entrepreneurship plays in economic and social development [9]. In Algeria, like many countries all over the world, the entrepreneurship is establishing nowadays an inevitable lever for the development and the strengthening of the economic landscape [4]. Entrepreneurship is one of the complex phenomena that combine the project of establishing the institution with the holder of the project in a certain environment. Like other professions, it is constantly evolving with the development of science and technology, and it is a profession with fixed foundations and rules, influenced by the environment in which it operates and by the individual variables that characterize the contractor. According to Vermeulen and Crijns (2007), the word entrepreneurship and economic prosperity cannot be separated [10]. On this basis, entrepreneurship is an effective tool in the development of the economies of developed countries due to its contribution to its achievement of added value and national development. Fighting unemployment and other strategic objectives, it is the new engine of the economy. In Algeria, several programs and solutions have been developed, such as pre-employment contracts and loans to encourage the creation of small and medium enterprises to absorb youth unemployment. With the beginning of 2009, the Algerian government has achieved the establishment of 100,000 small and medium-sized enterprises with the President's program. According to the statistics of 2015, 6% of the institutions active in Algeria are managed by women, on this basis, female's entrepreneurship in Algeria remains modest compared to neighboring countries [4]. The woman is now recognized as one of the sources of economic growth, job creation, innovation and wealth [3, 6]. Research on female's entrepreneurship dates back to the 1970s and has grown significantly in developed countries for more than 40 years, while still in its early stages in developing countries. The twentieth century was marked by the defense of women's rights and freedoms. Even researchers such as Stevenson (1984) went so far as to say that it was not worth the exclusion of female from the entrepreneurial field [4]. Research and studies on female entrepreneurship in developed countries such as the United States and France are on the rise, while few have been established in the Maghreb. Studies on female's entrepreneurship in Algeria are rare, but are trying today to open up new horizons for research, particularly by encouraging women through financial, training and sensitization provided by concerned parties. Our study is based on the idea that an analysis of female's entrepreneurial intention can reveal a new approach different from male entrepreneurship. Fishbein and Ajzen (1980) are among the first researchers to address the subject of individual intentions through a model they call reasoned action theory [2]. According to this theory, individuals' attitudes and Subjective norms result in the ability and will to control their behavior. This means that the behavior of the individual is voluntary and under observation of the individual who wishes to adopt it as a decision for his actions [2]. Ajzen (1991) corrected the shortcomings that characterized the theory; he said that the voluntary behavior is permeated by some shortcomings, as there are some behaviors that go beyond the scope of voluntary control of the individual [1]. On this basis, the researcher added to the reasoned action model the variable of perceived behavioral control, and called his new model the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Another example of this type is the Chapero and Sokol (1982) model, which is called the entrepreneurial event. According to proponents of this model, entrepreneurial intention can arise because of the negative circumstances experienced by the individual (divorce, immigration, expulsion from work,…), Intermediate conditions (eg, out of army, school, or even prison), and there are positive influences (family, market opportunities, potential investments, etc.) [27, 12]. In order to analyze the phenomenon of female Entrepreneurship, theorists and researchers must know the factors that promote the establishment of the entrepreneurial intention of the latter, in other words factors affecting the intentions of female in the establishment of small or medium enterprises. On this basis, we will attempt to focus on the individual variables (personality, risk-taking, motivation and attitudes towards the behavior) of entrepreneurship, and study the extent of their impact on the intention of entrepreneurship in university students. Therefore, based on the above we will try in this article to answer the following problem:How do individual factors affect the entrepreneurial intent of female university students?In light of the questions and objectives mentioned above, we suggest the following main hypothesis:There is a causal relationship between the individual factors (personality, motivation and risk) and attitudes of university female students towards the intention of entrepreneurship.On this basis, we aim to confirm the fact that female's entrepreneurship can succeed only if individual determinants are consistent. Therefore, our study aims to: (1) Clarify the theoretical and conceptual foundations of the subject of female's entrepreneurship and improve their understanding of the environment; (2) Identify individual factors that affect female's entrepreneurial intentions; (3) examine the relationship between different individual variables or factors that effects entrepreneurial female's intentions; (4) to test the theoretical model by selecting a representative sample of female who have intentions to establish an institution; and (5) to ascertain the positive or negative impact of individual determinants on the intentions of the establishment of enterprises by the entrepreneurial female by the method of structured equations.

2. Theoretical Background

- The feminist component contributes in one way or another to the economic growth of many countries in the world, according to Bruyat (1993); Filion et al. (2008); Constantinidis (1993); and Cornet (2006) Since the beginning of the eighties it was noticed that in developed countries such as Canada, the United States, France ... that research on the subject of female's entrepreneurship is increasing [6]. While other studies have focused on the motives of female entrepreneurs, their personal characteristics and their relationship to the environment they work in, and difficulties in establishing their own project, … [7]. Despite these studies, the number remains small when compared with the study of the intentions of the enterprise that focused on the male element. According to statistics published by the Center for Research on Women's Trade, in the United States, 47.7% of enterprises are run by women [7]. According to Orban (2001) in Canada, 47% of enterprises are run by women, 22.4% are in Italy, 28% in France of all institutions are run by women [4], Tunisia 15%, Cameroon 53%, while in Algeria it was 1.7% in 2004 and 4% in 2010 [6]. The tendency of most research (from 1991 to present) that dealt with the entrepreneurial intention towards the male element is what led us to choose a women's entrepreneurship that is no less important than male entrepreneurship.During the past years, many approaches have been employed in explaining the phenomenon of entrepreneurship, especially by trying to identify the factors affecting the construction process. According to Salah (2011), there is research that focused on procedural methods related to the phenomenon of entrepreneurship (identification of opportunities, organizational emergence, entrepreneurial vision, entrepreneurship project ...), and there are studies interested in the study of entrepreneurship through the variables of personal and demographic characteristics [26]. In this regard, due to its intermediate nature between external variables and the construction process, the stage of intention in the entrepreneurial process deserves more attention. In fact, the theoretical combination (psychology, management, sociology ...) has contributed to encouraging the exploration of the concept of intention. The study of intention in the perspective of entrepreneurship is a good research strategy that enables the owners of institutions to reveal the uncertainty that prevents the success of modern institutions. According to Krueger et al. (2000), entrepreneurial adventure is a voluntary and conscious process [18]. For this reason, Bird (1988) regarded entrepreneurship as a planned behavior. Ajzen (1991) Preceded by intention, on this basis entrepreneurship is considered as a multi-step process [25].We have noticed that in recent years, researchers in the field of entrepreneurship have become more inclined to focus on entrepreneurial intention as a key element in understanding the process of establishing new business [19]. Ajzen (1991, 2001) suggests that intention is the best indicator of predicting an individual's behavior because it is the first step of the entrepreneurial process, which explains why it is imperative to pay attention to it [20]. In this regard, Ajzen (1991) emphasized that the stronger the intent, the greater the likelihood of a tendency towards behavior. On this basis, entrepreneurial intention plays the role of mediator or catalyst that paves the way for the establishment of an institution [14]. The entrepreneurial intention has become a vibrant field of entrepreneurial research [15]. Hence, it is important to measure the intention to study the factors that encourage or inhibit the entrepreneurial capacities of a particular audience, especially the female component. According to the results of these studies [eg: Krueger and Carsrud (1993); Davidsson (1995); Reitan (1996), Kolveired (1996); Autio et al (1997); Begley et al. (1997); Tkachev and Kolveired, (2004)], that all voluntary behavior is preceded by the intention of the transition to this behavior, and that the intention of creation is linked to the attractiveness of this choice for the individual and his awareness of the feasibility of the project [4]. The use of these models, however, remains useful in verifying students' mental state, to determine the levels at which their entrepreneurial spirit is likely to freeze or explode. The scholars agreed that most of the models dealing with the subject of entrepreneurial intention are derived from two main models: Ajzen (1991), the theory of planed behavior (TPB), which is rooted in social psychology, and the model of the entrepreneurial event (FEE) of Chapero and Sokol (1982), Krueger and Brazeal (1994), Krueger (2000) and others (2000) have pointed out that these two models are complementary and powerful [28].

3. Hypotheses Development

- The theoretical model we will address in our research is derived from the model of the theory of planned behavior [1], according to this model, the entrepreneurial intention is influenced by three main factors: attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Through the theoretical model of this study we will try only to focus on the perceived subjective norms that are supposed to have an impact on the intentions of the female university students, on this basis and to express the variable subjective norms, our choice was personality, motivation, risk-taking.

3.1. Personality and Entrepreneurial Attitude

- According to economic literature, many entrepreneurial characteristics are influenced by the personality of the individual who has a positive attitude towards them, so that the position towards this entrepreneurial character is the contractor's personality [11]. The personalities include all the mental and physical qualities that are in a state of interaction with each other and integrated into a particular person living in a particular social environment. It also represents the dynamic organization that lies within the individual, which organizes all the psychological and physical devices that dictate his own character to adapt to the environment in which he lives. Many studies have examined the qualities and characteristics of the entrepreneur, for example: the need for self-realization [eg, McClelland, 1965]; internal control [eg, Brockhaus, 1982]; turn a blind eye to mystery [eg, Sexton and Bowman, 1986]; the tendency to risk [eg, Bellgley and Boyd, 1987; Brockhaus, 1980]; or proactively [eg, Battistelli, 2001] [29]. Some research such as Hisrich, (1975); Shartz (1976), Hisrich, et al (1995), Klofsten and Jones-Evans (2000), has shown that there are similarities between male and female and that both seek to be dynamic, independent and goal-oriented [6]. In contrast, other studies such as Sexton and Bowman-Upton, (1990), Smith, et al (2001), show that female tend to be opportunistic and adapt very easily [7]. Iyer (1995) said that the men who investigated the field study were less afraid of failure and more cautious than female [17]. Seet et al (2008) summarized the results of a comparative study between the personal characteristics of male and female entrepreneurs where they found a difference between these two genders in the following characteristics: [eg, Baumeister and Sommer 1997), conclusive (eg, Beasley, 2005), secrecy (eg: Feingold, 1994, Gohnson and Powell, 1994) targeted towards the goal (eg: Beasley, 2005) cautious (eg, Feingold, 1994), risk-taking (eg: Byrnes and Miller, 1999, Arch 1993), leadership (eg: Gohnson And Powell, 1994] [6]. According to Benhabib et al. (2015) The required personality traits in successful women entrepreneurs is: the ability to communicate, understand others, the ability to collect data from the environment, good bargaining, able to build and maintain good relationships, in addition to autonomy, The ability to identify and exploit opportunities for creativity, to be prepared to take risks even if it puts them at risk [8]. Luthans (1989) explained that personality is one of the most influential factors in a contractor's attitude and culture [4]. On this basis, we can propose the following first hypothesis:H.1: Personality has a positive effect on entrepreneurial attitude

3.2. Motivation and Entrepreneurial Attitude

- Pioneers in the field of motivation have shown that there is a great diversity of entrepreneurs’ motivations, which are often addressed as the drivers of success. Motivations determine how the actions and behaviors of individuals will be driven. Among the work on the area of entrepreneurial motivation that deserves to be analyzed are Shane, Locke and Collins researches (2003). These researchers found that human activities are determined by two sets of factors: motivational factors and cognitive factors. Therefore, they proposed a model in which they have integrated the motivational factors (the need for self-affirmation); aspects of motivation (goal setting and vision) personal characteristics (risk-taking, attitude of control, fear of ambiguity, belief in effectiveness); cognitive factors; context and stages of the entrepreneurial process to explain how motivation affects Commitment to entrepreneurship [22]. The entrepreneurial decision for these researchers is considered to be an evolutionary process through which the individual chooses the opportunities, the decision to exploit them, assess their feasibility, search for the resources they need, the mechanisms of exploitation and exploitation of opportunities. From a very general point of view, acting towards a certain circumstance is a process associated with adaptation functions. This concerns humans when they adapt to the conditions they face in the social and cultural environment that humans themselves define and which they do not have prior information about [16]. Therefore, the impulse to act is a process that results from a need, a feeling, and a complexity that generates the force that drives the individual to move towards a goal that will be justified by the individual to enable him to resolve the tension, provided that the cause is not of a vital nature [21]. According to Shapero and Sokol (1982), the motivation by which an entrepreneur is created is either because he wants to escape from the negative conditions (escape from unemployment, imprisonment) or to seize opportunities in new markets or products (self-realization) [27]. Motivation is a source of energy, but it is also crucial to know how to manage a project or to run a particular group. In this regard, we can put forward the following hypothesis:H.2: Motivation has a positive effect on entrepreneurial attitude

3.3. Risk Taking and Entrepreneurial Attitude

- More than 20 years ago, Mac Crimmon and Wehrung (1985) recognized that "risk consists of two elements: the degree of situational risk and the willingness of individuals to take risks"[13]. For a long time, researchers in the field of entrepreneurship have reinforced the idea that establishing an enterprise is a risky behavior, trying to prove that willingness to take risk or risk appetite is a personal feature that distinguishes between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs. The entrepreneur can take risks (financial, psychological…) without relying on anyone. In this case, he is not afraid to face the difficulties. On this basis, he is careful of everything and takes the necessary measures to deal with sudden cases. So, risk is a psychological trait, every entrepreneur is forced to take risks in all his decisions [28], so he decides and chooses in uncertain circumstances, but he takes the risk in the hope that his choice will be right [24]. Feeling the risk by establishing an institution that is dominant for both men and women, but most of the studies undertaken in this regard [eg, Arch, 1993; Byres, 1999; Bouffartigue, 2002; Bounetier, 2000]. Pointed out that women are generally less risky than men, they seek to gather more information to mitigate potential risks in entrepreneurship. According to the study by the Fayolle et al. (2008) to recognize the threat negatively affects the entrepreneurial intention while the perception of risk as an opportunity has a positive impact on the latter [13]. Based on the above, we put forward the following hypothesis.H.3: Risk-taking has a positive effect on entrepreneurial attitude.

3.4. Attitude and Entrepreneurial Intention

- Attitude is an obligation towards something, a judgment taken on a person or something, and a deep cause that leads the individual to act according to his present state [1]. It is also defined as the sensation or evaluation of the reaction towards an idea, something or circumstance. Therefore, an individual's attitudes have predispositions to adopt a specific behavior; those precedents consist of cognitive components associated with perceived, personal, opinion and belief risks. Ajzen (1991) defined positions as valuing something in the sense of the degree of attraction or alienation of the individual towards something or a behavior. It is about self-positions, as if the individual says to himself, "I love the profession of entrepreneurship". It is this sense that determines the intention that leads to behavior and makes it say, "I will start establishing my own institution" [1]. In this context, studies conducted by Trafimow and Finlay (1996); Sheeran, et al (1999) have shown that the normative control of attitude on an individual's intention to something is not only related to the type of behavior (individual vs. public) but also by the type of the individual (The control of individual normative attitudes independent of the type of behavior) [11]. The researchers mean by this, that the intention controlled by the individual attitude makes the latter predict his behavior better than the non-personal normative intention. In this context, Shane and Venkataran (2003) emphasized that entrepreneurial behavior is self-determined, meaning behavior caused by the same person, unlike the behavior of other people or something else [4]. According to the theory of self-determination advocated by Deci and Ryan (1991), the will of intent-driven intentions is internal (related to one's own experience) and therefore highly likely to be embodied on the ground [22]. Based on the above we propose the following hypothesis:H.4: Attitude has a positive effect on entrepreneurial intentAll of the variables mentioned above are supposed to affect the entrepreneurial intention that consists of a series of successive stages, from the person's personalities ownership, motivation and risk-taking to contracting to the entrepreneurial intention. These stages mediate the positive attitudes towards the entrepreneurship (see Figure 1).

| Figure 1. The research Model |

4. Method

4.1. Sample

- The data analyzed in the present study was compiled in Algeria. The size of our sample is 120 female university students. We hope that this sample selected from the research community at the faculty of economic sciences at the University of Abou Bekr Belkaid Tlemcen will allow us to reach express estimates so that we can understand them in the society from which they were taken. The highest age group was between 18 and 22 years of age, reaching 38%, then between 22 and 26 years, 36%, and those over the age of 26 were only 26%. The distribution of ages was logical because the students of the Master and the License are mostly aged between 20 and 25 years old.

4.2. Measure

- To measure the variables that make up the theoretical model of our research, we used 44-items form, so respondents had to express their opinion on these items by using the five-degree Likert scale, starting with 1 "strongly disagree" to 5 "Strongly Agree". The items were divided as follows: Twelve (12) items to measure students’ personalities, eight (08) items devoted to measuring risk-taking, Ten (10) items for motivations, nine (09) for students attitude, and entrepreneurial intention has been allocated five (05) items.

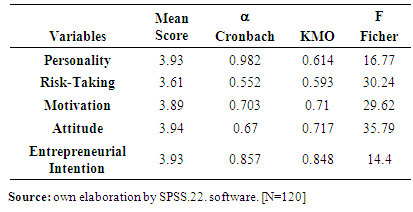

4.3. Reliability Test

- To test the reliability of the items we conducted exploratory analysis using the SPSS.22 software. Data analysis outputs and reliability indicators are shown in Table 1. At this stage we tested the stability of the items using a α Cronbach coefficient, whose results were near to 0.7, we also performed varimax measurements, which enabled us to get rid of items with a KMO more than 0.5 and we were sure of Bartlett spherical. ANOVA analysis of variance was good because the results of Ficher test were all significant. The results also indicated that most of the responses tended toward approval because the mean average was greater than 3 and the standard deviation was weak (less than 1.5). The explained variance ratio for all variables exceeded 50% and this result is encouraging because more than half of the variables were explained in the model. After conducting an exploratory analysis of the form, we verified the statistical stability of the items, which means that we can move to the empirical analysis.

|

4.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- The aim of this analysis is to ensure that the theoretical model conforms to the tested model using fit index and then verify the global contribution of measured variables (items) to the measurement of the underlying variables (theoretical model), through the λ coefficient, and finally confirm the shape index using the skewness and the kurtosis measurements. The method of estimation used in this analysis was GLS-ML. The absolute fit index (GFI, AGFI, PGI, APGI) were between 0.6 and 0.9 and RMSEA and RMS were near to 0.08 and the econometric matching index (CH2/Df = 1.85). Therefore, these results are in the acceptance domain which is « 2-5 ». In general, the results were good and confirmed that the results obtained through the questionnaire were consistent with the theoretical model of the research. The results showed that the measured variables can be used to measure the structural changes of the theoretical model of the study, since their global contributions « λ » were mostly more than 0.5, and was significant because the student -test was significant (>1.96). Scale measures related to the Skewness values were all negative and confined between 0 and -1, and indicate that the torsion is negative and close to symmetry. This result indicates that the larger number of responses was greater than the Likert scale which is « 4 », meaning that its entirety was 3, 4 or 5.

|

5. Results and Hypothesis Testing

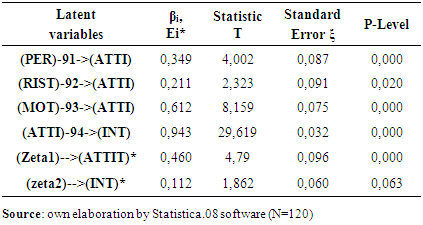

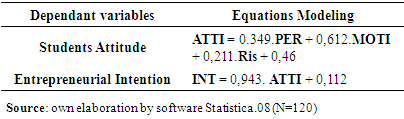

- In order to test our hypotheses, the significance of the correlation coefficients (βi) should be as certained. In order for this parameter to be validated, the data must have a normal distribution, so the student's test should be greater than 1.96 and his significant level (p-level) less than 0.05. The correlation coefficients were significant and allow us to move on to hypothesis testing. Through the statistical test of the first hypothesis, there was a statistically significant correlation between the personality of female university students and their attitude of entrepreneurship [H1: β1 = +0.349, T>1.96, p<0.05]. This finding shows that the value of β1 is positive (34.9%). This indicates that the positive relationship between the two variables is somewhat weak. Therefore we can say that the first hypothesis is true. For the second hypothesis, the value of β2 expresses the degree of influence of the drivers on the attitude. We note that the result is approximately 21%. This indicates that the relation between the two variables is positive, because the results were encouraging [H2: P<0.05, T>1.96 β2=+0.211]. This result confirms the validity of the second hypothesis, which indicates the positive impact of the motivation of students on their attitude on entrepreneurship. The results of the statistical analysis of the third hypothesis showed that the relationship between the risk-taking of the female students and their attitudes toward entrepreneurship, [H3: β3= +0.612, T<1.96, P<0.05], so that the test results are significant. We see from the results that the risk-taking of female students explains only 61.2% of their attitude toward entrepreneurship. Therefore, this finding confirms that the risk-taking component of the female students is somewhat weak. However, we conclude that the third hypothesis is acceptable. The results of the statistical test of the effect of student attitudes on their entrepreneurial intentions were good [H4: β4= +0.943, T <1.96, P<0.05]. It is clear that the value of the coefficient β4 is much closer to one (1) below the level of significance less than (0.05) and the student T greater than (1.96). This value indicates the severity of the impact that the attitude of female university students on entrepreneurship has on their intentions in establishing the business, as this confirms the nature of the positive relationship. The type of relationship between these two variables is direct and linear. So we can say that we have verified the validity of the fourth hypothesis. The results of the regression coefficients for the first and second equations (The equations model are shown in Table 3) indicated that positive relationships were recorded between the independent variables and the dependent variable which is the entrepreneurial intention. However, we note that the degree of influence exerted by independent on the dependent variables is varying, it was somewhat weak between personality and risk with attitudes (β1= +0.349 and β3= +0.612) and good between students' motivations and their attitudes toward entrepreneurship (β2= +0,211), and very good between the latter and the entrepreneurial intention (β4 = +0.943).

|

6. Conclusions

- In this study, we tried to study the factors that drive female to carry out entrepreneurship, so we have high-lighted the individual factors that affect the intentions of female university students. Theoretically, the theoretical model of the research consists of three possible relation-ships between the individual factors (personality, motivation, and risk-taking) and the attitude of entrepreneurship and between the latter and the entrepreneurial intention. Empirically, the results of our study have enabled us to know the impact of individual factors on the attitudes and intentions of the university graduates. The results of the study revealed the importance given to the concept of entrepreneurial intentions and confirmed by the theory of planned behavior, especially the highly positive effect of the attitudes of female students on their entrepreneur-ship intentions.The main results that have attracted our attention in this study can be summed up in the impact of female students' motivation on their approval of entrepreneurship, which explained the effect of the latter on their intention in the establishment of the business, while the effect was not strong on the personality and risk-taking on their approval of the entrepreneurship. The reason may be due to environmental variables along the lines of social, cultural and demographic criteria. The fact that university students belong to a Muslim community can have a negative impact on their entrepreneurial intentions, and this influence can be generated by culture or family.With regard to research limitations, this study can be extended to environmental variables such as cultural and social factors. This is necessary and it is possible to limit the specific variables of the entrepreneurial intentions and enable a good understanding of this phenomenon.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML