-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2018; 8(1): 18-27

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20180801.04

Belt and Road Initiative: Positioning Zimbabwe for Investment Opportunities

Rangarirai Muzapu, Taona Havadi, Kudzai Mandizvidza

Business School, University of International Business and Economics (UIBE), Beijing, China

Correspondence to: Rangarirai Muzapu, Business School, University of International Business and Economics (UIBE), Beijing, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In 2013, the Chinese government launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), with the objective of enhancing international connectivity and, consequently, boosting global trade as the road map towards globally shared and coordinated economic growth. This study puts forward a proposition that there is space for more countries to derive economic benefits therefrom. In this regard, the study discussed opportunities presented by the BRI, with a view to convince those countries that are yet to join the initiative, in particular Zimbabwe, to try and position themselves strategically. The study largely adopted a qualitative approach, through utilizing literature from desktop publications, interviews, speeches, meetings, seminars and conferences. The study revealed that the BRI’s envisaged massive increase in infrastructure and trade development will trigger an increase in demand for commodities and countries such as Zimbabwe will not only take advantage of the supply gap, but will also benefit from the enhanced connectivity to transport and trade these commodities. However, in order to derive maximum benefits from the Initiative, Zimbabwe should take advantage of her strengths and address her weaknesses to tap into the huge yawning opportunities.

Keywords: Belt and Road Initiative, Coordinated development, Shared growth, Connectivity, Synergy

Cite this paper: Rangarirai Muzapu, Taona Havadi, Kudzai Mandizvidza, Belt and Road Initiative: Positioning Zimbabwe for Investment Opportunities, Management, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2018, pp. 18-27. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20180801.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

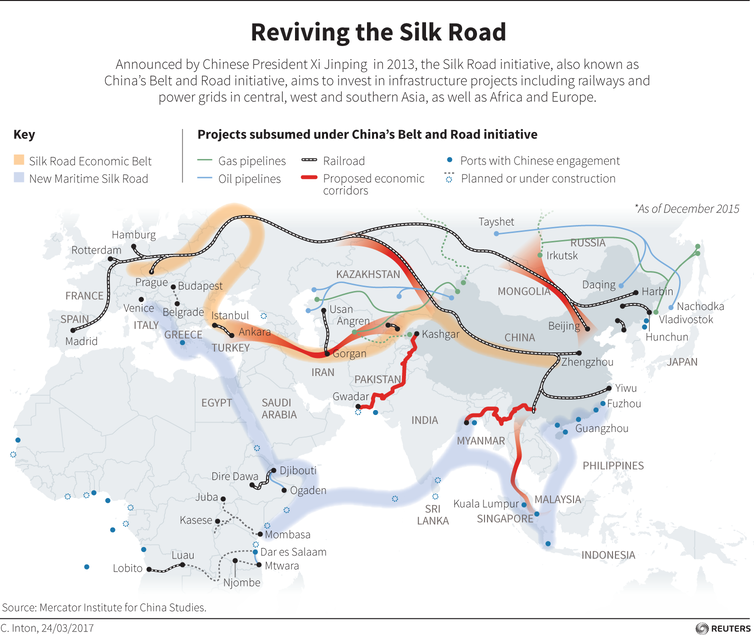

- From the outset in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative was not touted as a new creation, as it was a modernization of the historical Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Route, linking China at the centre of development. It is an initiative by China to revive its historic links to spawn a development wave across Africa, Europe, Central, Western and Southern Asia. It is also a wave entailing the construction of railways, roads, power grids, pipelines and economic corridors. Infrastructure development is in fact only one of BRI’s five components that included strengthened regional political cooperation, financial integration, unimpeded trade and people-to-people exchanges.The Initiative stemmed from China’s own economic realities, internal spatial economic imbalances and national gaps between China and its trading partners, a gap so yawning, that would threaten its own national development, peace and security. This realization and formulation of this Initiative is a replica of the “Theory of Coordinated Development”, which is being rolled out across the globe.By design, the BRI anticipates to serve as the nucleus of global development, a stimulant that is hoped to be embraced by all targeted nations. The authors of BRI also created financial vehicles to facilitate the implementation of the Initiative by setting up special lending plans. The vehicles are in the form of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Financial Centre for South-South Cooperation, the Silk Road Fund, China Development Bank, Export-Import Bank of China and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). The single thread that runs through all these funds is the Chinese presence and leadership role.Chinese leadership contends that infrastructural development is a precursor to economic development and growth, which precisely explains the nature of the projects covered under the Initiative.In Africa, one of the BRI’s entry-point is Kenya, where a rail line has been constructed to link the East Coast to the hinterland, with prospects of linking up many other countries.It is for that reason why it is argued that Zimbabwe should reach out and link up with the Initiative in Africa and the world at large. It is further observed that a proper positioning of the country entails formulating appropriate and conducive investment models and regulations, which would ultimately culminate in the increase in foreign capital inflows into the country.It is also noted and proven how crucial it will be for Zimbabwe to create Special Economic Zones and Industrial Parks in order to capture one of the investment strategies that the Chinese are eager to invest on. This study, therefore, seeks to dissect the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in relation to its origins; objectives; and the opportunities it may present and, furthermore, to advise and/or make recommendations on how countries like Zimbabwe and other countries that are currently not members of the BRI may position themselves to fully and effectively draw benefits from the initiative.

2. BRI Background

- The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) refers to the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which was proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping, in September 2013, with the aim of reviving and upgrading the ancient Chinese trading routes linking Asia, Africa and Europe, emphasizing cooperation between China and the world (Xiaoming H, 2017).The initiative’s underlying vision is that investing in such extensive infrastructure projects would trigger and sustain continuous global development, as a result of improved connectivity and integration of China with its global economic partners. That would also promote cooperation between and among the countries involved in the project web. The initiative ties in well with Zimbabwe’s thrust to pursue infrastructure and trade development.BRI also implicitly aims to create an outlet for China’s production overcapacity as well as open new export markets for Chinese commodities. This will entail exporting Chinese capital, products, and/or firms to operate and produce in the identified economies, hence, the need to cooperate with countries that are failing to meet the needs of their markets on their own.The Initiative would also help to realign China’s spatial imbalance in domestic economic development between the eastern and the western regions. The Eastern provinces of China are generally more developed and host the bulk of the country’s processing and high-tech industries, while the western provinces are predominantly primary sector industrial regions. Thus, the Initiative also seeks to stimulate processing industries in the western provinces such that they become supply zones to countries that border China along its western and south-western borders (Kuhn R, 2016).Ravi B, (2017) concluded that the BRI is, however, is not an organization and hence it has neither any structure nor constitution. It is a loose network of roads, rails, pipelines and waterways linking China by land, air and sea to parts of Asia, Africa and Europe. Ravi (2017) went on to note that if points are to be connected to carry goods, services or information, the consent of each relevant sovereign authority is required. Every link will also need to be viable and thus custom-designed to suit the concerned parties hence consultation and agreement are developed accordingly. However, at any given time, the network as a whole can only be presented as a concept. Individual countries can choose what to take, what to leave and how deeply to get involved in the network.

3. Motivation

- The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), seeks to promote shared economic growth amongst the nations of the world, with China at the center of that process (Hubbard P, 2015). The global community and Zimbabwe in particular, will benefit from participating in the initiative, as it would provide the platform for participating countries to strengthen their connectivity and, thus, help improve their economies in order to meet the aspirations of their respective citizens. Furthermore, in embarking on this study, the authors were motivated by the fact that Zimbabwe has been experiencing very low levels of both local and foreign direct investment, relative to its neighbors. Therefore, it was imperative to find out what could be done to ignited interest in the prospects of investing in Zimbabwe, with both the domestic and international community expressing desire to invest in the various spheres of the economy.While other regions were enjoying increased investment from China, Zimbabwe seemed to be lagging behind. It was observed that Zimbabwe largely got grants from China while other regional countries enjoyed massive FDI from China. This made the authors to explore possible ways to unlock Chinese investment in Zimbabwe.While the study particularly focused on the case of Zimbabwe, the authors believe that the proffered recommendations and ideas, though not exhaustive, could be generalized to other developing countries that may share similar economic characteristics with Zimbabwe. A careful application of the recommendations provided may also help these economies maximize on the opportunities that may come along with this initiative.

4. Research Questions

- i. What is the Belt and Road Initiative?ii. What are the potential benefits to countries that have already joined or those who may consider joining the initiative?iii. How can those countries willing to join the BRI get on board?

5. Methodology

- Data for the study was gathered through literature reviews, field research, speeches, seminars, conferences and meetings. Vast literature from desktop publications, national document repositories, and Zimbabwe government publications were used.Relevant stakeholders from Zimbabwe such as the Ministries of Industry and Commerce, Macro-economic Planning and Development, Finance and Economic Development as well as Foreign Affairs and International Trade were approached. Local business chambers and business people were also important sources of information.Interviews were conducted through various means such as telephone, email and social media platforms. Government officials from China and Zimbabwe as well as diplomats from Africa and Asia, among other officials, were interviewed. Other interviewees included officials from financial institutions of Zimbabwe and China, scholars, entrepreneurs, as well as media and researchers. To complement the above instruments, the researchers’ vast firsthand professional experience in both Zimbabwe and China made it easier to accomplish this study, especially where inferential judgments based on know-how were a necessity.

6. Conceptual Framework: Theory of Coordinated Development

- The BRI is primarily driven by the goal to realize regional, continental and global integration in various aspects of socio-economic development. The initiative calls for policy coordination, promotes connectivity through extensive infrastructure development, calls for the removal of barriers to trade, promotes financial integration and people-to-people connections, the idea is to make complementary use of participating countries’ respective unique comparative advantages through multilateral mechanisms and multi-level platforms. All this, is to facilitate shared and inclusive economic growth (Kuhn, 2016). It was envisaged that the plan would create mutually beneficial interdependency amongst the nations of the world and/or promote people-to-people connections. Essentially, the initiative would provide a mechanism for nations to complement each other in their respective development agendas. Thus, the Chinese leadership coined the BRI a ‘Coordinated or Common Development’ process (Kuhn, 2016).Kuhn, (2016) noted that the underlying strategy was that participant countries would focus more on their respective areas of comparative and/or absolute advantages and outsource in those areas where they were not competitive enough. In order to fully complement each other and promote mutually beneficial interdependency amongst the participant countries, a significant amount of bottlenecks in international development processes, including barriers to trade, would be tackled. The development process would eliminate or, at least, reduce diverse kinds of duplications and imbalances between countries and regions through the efficient allocation of resources and equitable access to resources. In the end, optimum economic growth would be realized. China is currently implementing an internal coordinated development between its provinces, urban and rural sectors, aiming to reach a balanced development scenario between regions and sectors by making not only large cities more welcoming to rural migrants, but also developing small cities, towns, and areas where rural populations now reside. This was also meant to stem the tide of rural-urban migration. To realize this vision, regional policies were modeled to better serve the different areas. The regions were also encouraged to have more interactions with other regions to facilitate industrial transition, partner assistance and cooperation (Kuhn, 2016; Zhang and Cai, 2015; Dang and Sui, 2015). Since the beginning of Chinese reforms in 1979, China's single-minded focus on economic growth generated inevitable problems, especially imbalances across geographical areas- urban and rural, the wealthy eastern/coastal areas and the underdeveloped central and western regions and between social classes. Moreover, uncoordinated economic competition amongst provinces and cities encouraged inefficient allocation of resources and exacerbated industrial overcapacity and duplications. The results called for a rebalancing of issues and getting provinces and cities to cooperate, as well as to compete, in order to optimize development. Yuan, Maozhou, Jinfei, Mingming and Reiyu (2014) provide a typical application and relation of this theory in their study of dynamic coordinated development of a regional environment-tourism-economy system in Western Hunan Province of China. Kuhn, (2016), therefore, summed that coordinated development “is especially important in China where provincial rivalries have contributed to industrial duplications and overcapacities. The challenge is to get provinces and cities to cooperate as well as to compete in order to optimize development”.If this coordinated development strategy could be applied in Zimbabwe, the country would realize progressive development across its regions, provinces and cities. Zimbabwe’s provinces and/or regions should be developed in a way that exploits their comparative or absolute advantages for the benefit of the society as a whole. There is need for close cooperation or linkages which then should result in synergistic advantages as opposed to the random development. These areas should, in a great way dovetail with the country’s national development thrust or vision. The country is, however, falling short of such coordinated development; the gap between the rural and urban sectors is too large, hence, the need to follow more organized and productive approaches. First is to establish a more friendly investment environment which would attract investors to put on their capital on the ground. The investments should prioritize developmental projects that further develop the community.On a global perspective, common or coordinated or integrated development is a shared development strategy. It is a situation when one region/country’s development does not translate to the underdevelopment of another. In fact, one region/country’s development should feed into the development of its trading partner(s). Each respective region/country would be concentrating on areas where it has a comparative or absolute advantage to the extent of producing surplus for the consumption of other regions/countries (China Daily European Weekly 11/04/2016, Kuhn 2016). This would encourage cross trading among them. In areas of comparative disadvantage, the region/country would import from other regions/countries that have comparative advantages in such areas. This is where the aspect of coordination comes in. The regions/countries may also agree on an operational framework to make sure that each respective region/country benefits fully from specialization and international trade even though they may be developing at different paces (Dang and Sui, 2015). In addition, a country needs to adopt investment and trade policies that complement with others in the region and the world at large, in order to enhance the smooth flow of goods and services.A typical example of the above scenario was articulated in Zhang and Cai (2015), where it is argued that sustainable globalization could be achieved if nations cooperate in their development activities as opposed to a few countries dominating the markets. Having fewer dominating countries on the market may present complicated market distortions.Africa’s economic and geographical regions may take a leaf from this strategy and develop their areas in a more coordinated approach, which would save them on costs and duplications.The BRI strategy, therefore, follows the theory of coordinated development.

7. Financial Strategy of the BRI

- In order to realize the fruition of this vision, China proposed establishing financial institutions as agents of the intended thrust, which would provide the requisite financial support for infrastructural development in countries involved in the BRI. The establishment of some financial vehicles, such as the China EximBank, the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Financial Centre for South-South Cooperation, the China Development Bank and the Silk Road Fund (SRF), among others, supported the initiative (Yipping, 2016; GFOA Best Practice, 2010). For instance, according to an official from China EximBank, bank’s thrust was to promote international trade cooperation between China and the rest of the world, through Chinese enterprises, foreign governments and corporate clients. Other institutions were also given similar mandates in order to broaden the base of financial support and to spread the risks across the board.

8. BRI as the Centre of Global Development

- The broad objective of the BRI is to put in place a mechanism to transmit China’s development experience to the global community. The Initiative is designed to be an inclusive socio-economic development model with China at the center of the process. The idea is that shared growth, with countries cooperating to tackle global economic challenges and injecting fresh energy into interconnected development, reduces global imbalances and brings prosperity to all (Hubbard P, 2015). The conviction driving the initiative is that countries do have the requisite resources and/or the ability to address economic problems on their own. The current fragmented and exclusive international cooperation model makes it difficult to integrate resources for mutual benefit, hence, the idea of developing a global link to address the problem of stagnation. Through the BRI, China envisages a trans-regional integrated global economy that is open and liberal. While some Western countries such as the USA and Britain (Brexit situation) were closing their economies, China was standing out against unnecessary protectionism. The act was likened by Drysdale (2014) as locking oneself in a dark room (Drysdale P, 2014).

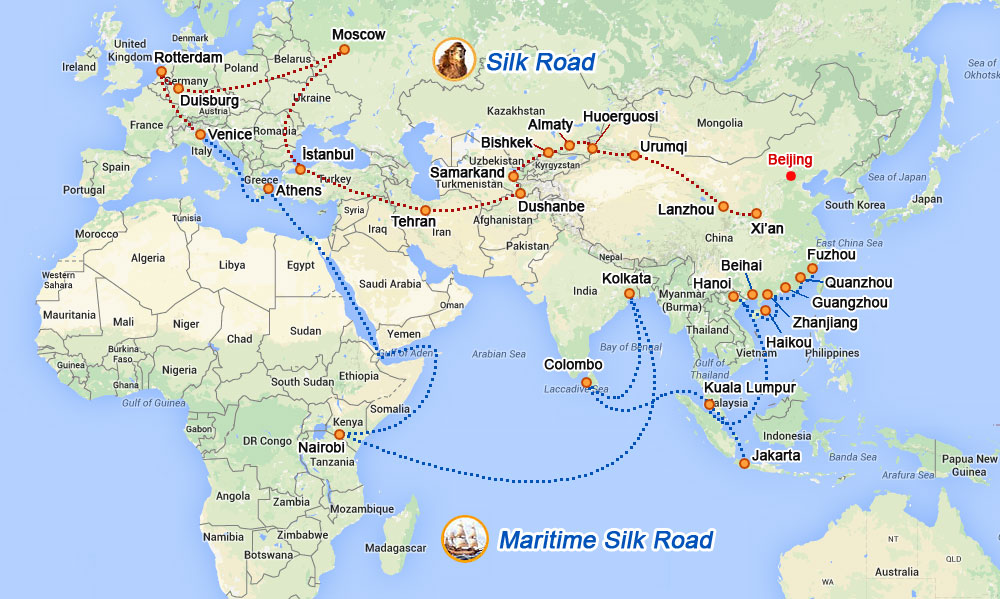

9. Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road

- The BRI took precedence from the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road concepts (figures 1 and 2). It is an improved version of the two concepts. Li Q, (2009) highlighted that, the ancient Maritime Silk Road was a crucial conduit for trade and cultural exchanges between China's south-eastern coastal regions and countries in Southeast Asia, Africa and Europe. It was first formed in the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 B.C.-220 A.D.), developed from the Three Kingdoms Period to Sui Dynasty (220-618 A.D.), flourished in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1279 A.D.), and fell into decline in the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368-1911 A.D.). Through the sea route, silk and tea were exported, while spices and rare treasures like precious stones were brought to China.Li Q (2009), remarked that in ancient times, trade ships sailed along the Maritime Silk Road driven by monsoons and ocean currents, bringing business and trade convenience to the countries and people along the route, while enriching the cultures of local societies. This is what the BRI is seeking to resuscitate as illustrated by Figure 2 and 3 taking its origins from Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. (Source: euap.hkbu.edu.hk) |

| Figure 2. The Belt and Road Initiative: Reviving the Silk Road. (Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies) |

| Figure 3. China’s Belt and Road Initiative. (Source: http://www.globaltrademag.com/global-logistics/chinas-belt-road-initiative-mean) |

10. Discussion and Findings

- Zimbabwe has glaring investment opportunities, which could be taken advantage of in attracting foreign direct investments. However, Zimbabwe should maximally utilize the opportunities that exist from the BRI and the rest of the world.Considering the openness and inclusive nature of the BRI, the active participation of all countries, as well as the international and regional organizations is welcome. In this regard, Zimbabwe is not an exception and may, in the future, benefit regardless of her geographical separation from the current main trade routes. While, in Africa, as indicated by Lin Songtian (2015), an official in the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the BRI has hitherto shown more tangible impact on the Eastern African regions. It can be argued that the initiative would, with time, have positive knock-on effects on the whole African continent and beyond.Thus, it is the authors’ view that, although Zimbabwe is not one of the countries directly involved in the BRI, the country could tap into the opportunities through other windows, particularly through the positive multiplier-effect that the BRI is expected to generate on the global economy. For instance, the BRI is premised on the idea of extensive infrastructure development to enhance connectivity amongst the countries involved. That would boost global trade by way of enhanced access to markets and raw materials. The extensive infrastructure development would also mean increased demand for products like iron and steel for use in constructing such infrastructure. Zimbabwe has an abundance of coal and iron ore, which are needed for steel production. Both the mining of these minerals and the entire value-chain of beneficiation would inject the much needed foreign direct investment. Ceteris paribus, the increased demand flowing from BRI’s extensive infrastructure development would mean higher demand and possibly increased returns for the commodities Zimbabwe sells on the global market. That would mean more revenue and better capacity for the country to finance national development projects. That would also mean increased employment opportunities.

10.1. Trans-Regional Integration

- Some countries on the African continent, including some of Zimbabwe’s regional neighbors, as indicated below, are involved in the BRI. For instance, the construction of the Mombasa-Uganda railway line that connects the East and Central Africa is part of the BRI (Lin Songtian, 2015). That line would join the Tazara railway line connecting Tanzania and Zambia. In essence, therefore, Zimbabwe would also be connected to the Mombasa-Uganda line since it is already linked by rail to Zambia. In fact, most southern African countries such as Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia and South Africa that are already interconnected by rail would also be able to access Central Africa and more areas in East Africa through the BRI’s Mombasa-Uganda railway line. Furthermore, there is the north-south corridor, linking South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe from Durban to the copper belt region in DRC and Zambia. This would mean enhanced market access for Zimbabwe and other countries in southern Africa even when they are not directly involved in the BRI. This also calls upon Zimbabwe to be alive to its neighbors’ economic development and respective environments in order to capture the positive economic spill-overs. Therefore, Zimbabwe should prioritize attracting private-public-partnerships (PPPs) among other progressive economic models such as the build-operate-and-transfer or build-own-operate-and-transfer, to speed up construction of basic infrastructure. It could also revisit to securitize its vast array of mineral deposits to guarantee funding for such projects which will have an enabling effect in the country and the region as well. That would enhance Zimbabwe’s attractiveness as an investment destination. It is a well-known fact that countries with developed infrastructure and efficient services receive more foreign direct investment compared to those with poor infrastructure and services. This is also the thrust of the BRI as it emphasizes that infrastructural connectivity would form the basis for sustained development and other things would fit along the way.The realization of regional and continental integration in Africa through BRI could also help Zimbabwe better tap into envisaged opportunities from the initiative. The BRI’s focus on infrastructure development and interconnectivity enhancement could also help speed-up continental integration, to make Africa a single economic bloc. Increased regional and continental integration through the facilitation of the BRI would present a great opportunity for Zimbabwe to boost its current exports. With the bulky nature of Zimbabwe’s top exports such as cotton, raw tobacco, ferroalloys, platinum, ferrochrome, and raw sugar, it will become much easier and cheaper as well as faster in reaching out to markets such as in the Middle East, Asia and Europe through utilizing more efficient rail, road and marine systems brought about by the BRI.Strategic Geographical Positioning: It is a fact that Zimbabwe is strategically located at the center of southern Africa region. This strategic geographical positioning gives Zimbabwe an advantage since the country has the potential to effectively serve as the hub for human, cargo and communications traffic as well as electricity transmission in the region. This places Zimbabwe at a favorable position to draw opportunities from the BRI in the context of projects designed to facilitate regional and continental integration.

10.2. Infrastructure Essential for Economic Growth

- To complement the above suggestions, Zimbabwe may need to construct adequate aviation infrastructure such as airports and other related facilities and services of international standards that can carry the largest aircrafts so that it may also act as a regional and international air cargo logistical hub. The current inadequacy of such facilities has led to reduced air traffic in the country, a situation that can be turned around by taking advantage of the geographical positioning of the country in the region. Infrastructural development in Zimbabwe and across the region as a whole is essential for economic growth, logistics and regional integration; hence the Chinese investors could take advantage of the current infrastructural gap to invest in the entire value-chain. Zimbabwe may also take advantage by improving its rail, road and telecommunications infrastructure so that it can take an important position to be the hub.

10.3. Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Opportunities

- The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) fund may also complement the BRI through the utilization of development funding availed for various projects in Zimbabwe. China has availed funds for loans under this initiative, where countries should apply for the funds. Countries should then provide bankable projects through the Chinese financial institutions, for approval and disbursement. The fund is given on a first-come-first-save basis. Unfortunately, Zimbabwe has not benefitted much on this. However, Chinese institutions such as Sinosure and China EximBank have observed that Zimbabwe, like many other African countries have been found wanting due to an array of technical deficiencies on their project proposals. It is, therefore, recommended that Zimbabwe should clearly follow the project guidelines and requirements to enhance chances of approval. By doing so, Zimbabwe, would have positioned herself strategically to gain access to capital resources from the FOCAC initiative. The FOCAC initiative is a multilateral Chinese-driven project aimed at developing and industrializing African countries. It was launched in the year 2000 as a multilateral cooperation platform between China and African countries (except Burkina Faso and Swaziland) and other African institutions to enhance exchange and cooperation in various fields of businesses. The cooperation entails, among other issues, politics, economics, social, culture and the environment that affect respective countries’ overall development (www.focac.org/eng).The FOCAC initiative fits well with the aims of Belt and Road Initiatives as they all aim to connect developments across the global economies, therefore, Zimbabwe should speed up its participation in the FOCAC initiative to realize maximum benefits.

10.4. Ease-of-Doing-Business Processes

- The Zimbabwe Ministry of Finance (2017) noted that, with regards to the ease of doing business, Zimbabwe’s ranking remains unfavorable, despite moving from 161 in 2016 to 159 in 2017 out of 190 countries even after the revision of the process. For instance, the Ministry of Finance (2018) concedes that the cost of doing business in the country in relation to taxes is still on the high-end. That includes taxes across all sectors. Company registration was still laborious and inefficient. The inefficiencies were also compounded by the non-functional of a one-stop-investment centre that would have made processing easier. Such inefficiencies do not promote business initiation, as well as luring of new investments. The country was, therefore, losing out on investment opportunities due to comparatively higher taxation. Government should, therefore, be seized to continue revising the business process to competitive levels. Such reforms should be more practical and administratively accessible for actual day-to-day transactions by both locals and foreigners intending to undertake business or investment in the country.

10.5. Financial Support Mechanisms

- As stated before, China has developed some mechanisms of implementing cooperation by establishing financial vehicles to avail funds for investment projects, such as the China EximBank and the China Development Bank. Furthermore, China also provides financial grants and donations to individual countries of their choice for purposes of spurring development (Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), 2015). Zimbabwe, thus, needs to work out strategies that would attract funding from such institutions. For instance, crafting projects with clear deliverables and ensuring that the project fits into the win-win bracket. Thus, for China to prioritize Zimbabwe’s projects, Zimbabwe needs to mould projects in which the Chinese see value in or projects that are not only bankable but generate a win-win pay-off for both parties. In addition, Zimbabwe needs to work on clearing her loan arrears with the global as well as the Chinese and other global financial institutions, which have been outstanding for years. That would enable the country to re-establish its credit worthiness and become eligible to access new funding (Moyo, 2018). Overtime, if this issue is not addressed, it would be extremely expensive and difficult to retire the outstanding debts. This might affect Zimbabwe’s current and future cooperation with Chinese financial institutions. The continued poor debt repayment record might also result in total financial blacklisting of the Zimbabwe government and its entities and halting of the disbursement of funds of on-going agreed projects. Without addressing these, among other issues, Zimbabwe may continue to be a spectator while other economies enjoy the massive inflow of Chinese investments.

10.6. Special Economic Zones and Industrial Parks

- While Zimbabwe, like other economies, is already in the process of establishing special economic development zones and industrial parks, the process needs to be expedited. The promotion of value-addition and beneficiation can be speeded up, by providing sector-specific incentives. The process is taking too long to be implemented, while other African countries such as Congo-Brazzaville, Djibouti, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa, Somalia and Tanzania are already setting up development zones and industrial parks, leading to Zimbabwe’s potential investors preferring such destinations (Chinamasa, 2018, Gono, 2017). Following the promulgation of the Special Economic Zones Act {Chapter 14:34}, in 2017, the Government of Zimbabwe should, therefore, accelerate the establishment of such Zones in order to attract investment and increase exports.The special economic zones can be an effective instrument to promote industrialization if implemented properly in the right context, as shown in some of the emerging countries, particularly those in East Asia. According to the Herald of Zimbabwe, of 8 February 2018, it reported that the results were mixed with some countries successful, including China, Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea, Jordan and Mauritius. More and more countries have begun to implement this instrument for their industrialization process, especially as a way of attracting foreign direct investment mostly in the manufacturing sector, creating jobs, generating exports and foreign exchanges.The idea of economic development zones that China is already exporting to some of its economic partners across the globe through the BRI, presents a number of attractive incentives to investors since they encourage productivity and easy way of doing business. China presents the much needed expertise on this aspect, which Zimbabwe could take advantage of. The SEZs are aimed at promoting value-addition and beneficiation, by offering targeted and specific incentives to qualifying investments. The zones are typically exempted from the normal bureaucratic processes of investing. Therefore, Zimbabwe needs to keep abreast of the recent industrial parks development concept to avoid being left behind when many other countries are adopting the economic development model.

10.7. Investment Climate Reforms

- The presentation to the business community of a clarified and revised Indigenization and Economic Empowerment Policy would go a long way in enticing the Chinese business community, and investors from elsewhere, to take up business opportunities in Zimbabwe (Ministries of Finance and Macro-economic Planning and Development, 2018). The amendment of the Indigenization and Empowerment Act should be expedited in order to ensure certainty for investors. The Act should then identify and remove legal barriers to entry currently contained in the legislation.Though the policy has since been partially revised, it remains to be implemented. The 51/49 indigenization threshold was largely viewed as a stumbling block as it communicated conflicting signals to the investing community. Once the business working environment is clarified, private capital/businesses would flow in since a number of Chinese companies are seeking viable investment destinations abroad where they can deploy and, or, utilize their excess capacities, along with development finance, technology, and knowledge base, which Zimbabwe can take advantage of. Therefore, it calls for the adoption of proper, consistent and transparent policies that make the economy a conducive and competitive investment destination. By doing so, Zimbabwe would be ‘building the nest for appropriate investors to lay their capital’. The Ministry of Industry and Commerce, (2016) and the captains of industry in Zimbabwe, indicated that the Chinese business is flowing in the direction of other countries in Africa such as Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, Eritrea and Uganda among other countries with better investment policies, shunning Zimbabwe, a thing that should be rectified.

10.8. Mitigating Investment Risks

- Alternatively, Zimbabwe may have to intensify the pursuit of other investment models such as Private-Public Partnerships (PPP), Build-Operate and Transfer (BOT), Build-Own-Operate and Transfer (BOOT). These models allow all economic players to venture into partnerships and implement projects using their own capital without overburdening the government. These models could help the country do away with potentially mounting foreign debts brought about by adopting the Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) model. It can also create room for new investment opportunities that require investors to use their own capital in Zimbabwe for mutual benefit in debt-free infrastructure development arrangements. A legal framework by way of the Joint Ventures Act should be put in place to facilitate such partnerships. This may lure Chinese among other global investors to weigh-in their options of investing.Meanwhile, in terms of sourcing development finance, the establishment by China of many other financial institutions for purposes of funding infrastructure development in countries involved in the BRI also means increased options to other economies, including Zimbabwe, This presents a wider array of options for investment financing, when compared to yesteryears where only the likes of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) dominated that market. When countries have more alternatives in terms of sources of development finance, the expectation is that the terms of borrowing such funds would improve. In this regard, Zimbabwe, which has a glaring infrastructure deficit, is likely to benefit by way of improved terms of borrowing development finance on the global market, including those from the Chinese market.

11. Conclusions

- The BRI avails a significant opportunity for Zimbabwe to build on its potential and to exploit its competitiveness across the region and the world at large. The BRI’s focus on extensive infrastructure development could mean greater demand for materials used in infrastructure development, which Zimbabwe produces in abundance. With developed infrastructure, it would also mean better access to regional, continental and global markets for Zimbabwe’s exports. This would give impetus to the economic development process in Zimbabwe. Therefore, Zimbabwe simply needs to position herself strategically to attract local and foreign businesses. Other developing countries may draw investment lessons from the case of Zimbabwe as they endeavor to position themselves to tap into the envisaged benefits from the BRI. Essentially, with the right business environment and attitude, there is a significant scope for virtually all developing countries to draw benefits from the initiative.

12. Way Forward

- The study has highlighted some of the gaps developing countries, specifically Zimbabwe, that should be worked on in order to fully benefit from the Chinese-driven BRI. The key is for the developing countries in question to be attractive to Chinese and other global investments. Furthermore, there is need to establish integrated strategies or synergies that seek to promote economic and industrial growth within a country or region.As, alluded to, the study specifically focused on the Zimbabwe situation. Perhaps, it would be worthwhile if similar studies could be conducted across Africa and other continents’ economic, geographical and political regions or countries, using a more quantitative approach in order to confirm and/or measure the opportunities associated to the BRI. Such studies may further highlight the strengths and/or weaknesses of the respective countries and/or regions, as well as expose additional threats and opportunities that may be generated by the BRI. That would help countries/regions make fully informed decisions regarding their membership/non-membership to the BRI. Nevertheless, this paper presents the general assessment of the BRI, highlighting the potential benefits of the initiative, while also giving suggestions on how a developing country could position itself to maximize benefits therefrom.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Sincere acknowledgments go to Memory Muzapu, Glenda Mandizvidza and Memory Havadi. Special thanks to the Embassy of Zimbabwe in Beijing for their support.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML