-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2017; 7(6): 209-222

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20170706.04

A Corporate Governance Perspective to State Owned Enterprises in Zimbabwe: A Case Study of Air Zimbabwe

Memory Mashavave

University of International Business and Economic, China

Correspondence to: Memory Mashavave, University of International Business and Economic, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The research made use of the case of Air Zimbabwe to analyse corporate governance practices in Zimbabwe’s State Owned Enterprise (SOEs). The research was prompted by the persistent poor performance and corporate failures characterising most SOEs in Zimbabwe. Air Zimbabwe has not been spared from corporate failures and corruption which has seen it relying on government subsidies to afloat. The research methodology for the collection of data involved the quantitative and qualitative techniques. When the data was collected, it was presented and analysed with the assistance of descriptive statistics which comprised of graphs, tables and descriptive narrations. A total of 48 Air Zimbabwe management staff, employees and Board members were surveyed through interviews and questionnaires. Results of the study indicate that there is poor corporate governance compliance at Air Zimbabwe which has led to corruption and lack of transparency and accountability. The results also point to the non availability of a written corporate governance policy which is supposed to guide the company in implementing corporate governance. In addition there is no performance monitoring mechanism for the Board members some of whom are appointed on political grounds without the requisite airline business knowledge. Given these shortcomings, the study recommends an overhaul of the enforcement machinery and establishment of a regulatory agency or framework to enforce compliance and transparency.

Keywords: State Owned Enterprises, Corporate Governance, Corruption, Transparency

Cite this paper: Memory Mashavave, A Corporate Governance Perspective to State Owned Enterprises in Zimbabwe: A Case Study of Air Zimbabwe, Management, Vol. 7 No. 6, 2017, pp. 209-222. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20170706.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Africa is faced with a myriad of challenges that turn away investors who can bring Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to the continent. Top on the list of these challenges are issues such as poor corporate governance, corruption, political interference and the absence of business ethics and principles. These challenges have seen State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) in Africa rely on the national budget handouts for their survival. In Zimbabwe, the national airline, Air Zimbabwe, is one such example of a loss making, non-performing SOE that is reliant on the government. Air Zimbabwe is characterized by huge budget deficits, debts, poor debt servicing, operational viability challenges that have led to aircraft being impounded in the UK as collateral. Other signs of failure include the withdrawal from lucrative routes, failure to meet company legal obligations and recurrent labour, industry and criminal court cases. Pro- government schools of thought attribute Air Zimbabwe’s poor performance to the aged fleet, a hostile operating environment, targeted economic sanctions, negative local and international publicity and travel bans. (Muli 2012). According to the (Annual Report 2014 for African Airlines Association & South Africa Airline Annual Report 2016), other airlines in the same and/or similar Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) market performed better than Air Zimbabwe. In the case of Air Zimbabwe, as at December 2010, the company recorded a loss of USD33 million with a negative cash flow of USD24 million (Muli 2012). The government has on several occasions convened boards of investigation and commissions of enquiry to investigate and develop turn-around strategies for the Airline but to no avail. Each investigation lead to top management reshuffle, labor disputes, retrenchments, payouts sinking the organization into further debt and loss of business.Good Corporate Governance seem not to have been addressed by any of the Boards or Commissions of enquiries and it is against this background that this paper seeks to establish the extent to which Air Zimbabwe conforms and or complies with corporate governance principles and highlight current effects of non-compliance on the operations, management, profitability, reputation and business transactions. This research is expected to assist Air Zimbabwe and other SOEs in similar circumstances to align their strategies through adopting sound corporate governance practices which should help to improve performance and profitability. The study also seeks to provoke further scholarly research into the area of corporate governance in developing economies.

2. Motivation

- The Researcher would like to contribute towards literature on corporate governance and reveal that failure to enforce corporate governance would result in failure by State Owned Enterprises. Having worked in the aviation industry, I have had the privilege to work closely with Air Zimbabwe and have seen its decline from 18 aircraft in 1980 to only 3 aircraft in 2016. This research is expected to assist Air Zimbabwe and other SOEs in similar circumstances to align their strategies through adopting sound corporate governance practices which should help to improve performance and profitability.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Overview of State Owned Enterprises

- In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) inherited a deteriorated economy from years of wars and under development (Li, 2002). There was an urgent need for economic development, employment creation and nation building. Before 1949, industries considered critical to government operations were nationalised and wholly controlled by the government. The Chinese socialist approach in managing SOEs resulted in increased production as well as more revenue to the fiscus. According to Li (2002), China used a multi pronged approach in managing SOEs in such sectors as defense, energy, telecom, aviation and shipping that is the government wholly owned enterprises as well as provincial wholly owned. The government and the province in these cases own 80-100%. The 20% would be owned by a legal person. Then there are the those with a mixed ownership, where the government owns a certain percentage and the enterprise is driven by market economy, for example, Huawei. So in all cases the government has some control. With this kind of set up, the Chinese SOEs have operated profitably and had positive contribution to the fiscus with some of them making it to the Fortune 500 listing in defense, energy, telecom, aviation and shipping industries. The Bottom line in the case of China is that the state owned companies are operating profitably and practicing good corporate governance.Russia has a similar SOE set up but limited to four industries: energy (oil, gas, and electricity), banks, defense industries, and transportation (F. J. Dresen, 2012). These industries are government controlled and comprise a huge source of income the national budget. The global challenge of SOEs stems from no clear-cut roles, limitations and functions of the owner, the regulator, and the board of directors, executive management and lack of accountability. The situation creates power struggles and poor decision-making processes. The Government doubles as the owner and regulator. The board of director are government appointees who, more often, serve the interests of the master than practice sound business ethics and override executive management. In the Western block, that is, the United States and Europe had the same path nationalizing public enterprises to revitalize their economies (N. Efird, 2010). During the Keynesian era, liberal forces felt that stronger control of some sectors of the economy could resolve the problem of market failure. The move was mooted after the realization of failures brought about by the market economy of the capitalist system, after the great depression. The nationalization of most public enterprises rekindled the Western economies and that was the way up until the 1980s. In the 1980s, ushered in a new era of privatization of enterprises to reduce inflation and improve (N. Efird, 2010). The literature reviewed on SOEs in China, Russia and Western countries such as the USA shows that there is evidence of the enterprises playing central roles in supporting the national income of their respective countries. In contrast, Air Zimbabwe has become a burden to the national economy by annually registering loses hence requiring the government to constantly intervene with financial support. This contrast, presents research gap which is worth exploring from the perspective of corporate governance. This study therefore seeks to contribute to the body of knowledge on SOEs through an in-depth study of Air Zimbabwe.

3.2. State Owned Enterprises in Zimbabwe

- Zhou (2012) observes that at the dawn of independence in Zimbabwe in 1980, the new government public enterprises thinly spread across all key sectors of the economy and with varying levels of state ownerships and all had positive impact to the national purse. They included the Rhodesia Iron and Steel Company, the Grain Marketing Board, the Rhodesia Railway Lines, the Agricultural Marketing Board, the Rhodesia Air Lines, the Cotton Marketing Board, the Tobacco Marketing Board, the Industrial Development Corporation, the Rhodesia Broadcasting Corporation, the Cold Storage Commission, the Sugar Industry Board, the Agricultural Finance Corporation, the Cotton Research Board, and the Maize Control Board, among others. According to Zhou (ibid) the new parastatal polices were designed to usher in equitable distribution of wealth, decentralizing industries, employment creation and creating a balance regional development program. As a result, by 2013 Zimbabwe had 78 State Owned Enterprises (SOE) spanning across almost all sectors of the economy, notably in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transport, energy, communication, transport and finance. Notable examples of these SOEs include the National Railways of Zimbabwe (NRZ), Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA), Air Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC), Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Authority (ZESA), Zimbabwe United Passengers Company (ZUPCO), the Cold Storage Company (CSC) and the Grain Marketing Board (GMB), the Zimbabwe National Road Administration (ZINARA), Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Authority (ZESA), Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (ZIMRA) and the Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC). Commentators on SOEs in Zimbabwe have pointed out that there is very little contribution to the economy from State Owned Enterprises (SOE) and the problems have been attributed to mismanagement and a poor corporate culture. Zhou (2012) observed that most parastatal boards were poorly constituted in terms of autonomy, membership and capitalization while parent ministers wield extensive powers over parastatals, often selecting investors and partners without consulting relevant government departments such as the State Procurement Board and Inter-Ministerial Committees. Viability problems currently dogging parastatals in Zimbabwe should be interpreted within the context of political interference and abuse of parastatals by senior management, lack of commitment and common vision within the leadership, line ministries and management of the enterprises. As a result, most of state companies in Zimbabwe are operating under untenable operational frameworks of dilapidated infrastructure and equipment, huge debts, undercapitalization, skills deficits, vandalism and looting by top ranking government officials and politicians. They are generally operating below optimal levels, failing to service debt and facing frequent threats of industrial action from employees. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (2004), noted the challenges facing SOEs included flouting of laid down procurement procedures, and in some cases, payments for “engineered-invoices; non-adoption of sound accounting and audit practices in financial management; lack of strategic planning at Board and Executive Management levels and lack of Board oversight on management decisions and operations.Despite the launch of the corporate governance framework document in 2010, legislation is yet to be put in place delineating duties, responsibilities and separation of powers of stakeholders (the Owner, Regulator, Board and Executive Management). To further dissect the nexus between corporate governance and performance of SOEs, this study seeks to examine corporate governance practices at Air Zimbabwe with a view to making recommendations. However, before delving into the study in depth, it is necessary to provide the background to Air Zimbabwe. According to Muli (2012) Air Zimbabwe Private Limited is an airline wholly owned by the Government of Zimbabwe. The Airline’s market is mainly made up of Zimbabweans (75%), resident both locally and internationally, with other nationalities constituting the remaining 25% (Air Zimbabwe Holdings Operations and Service Improvement Plan: 2007). Despite massive budgetary allocations to Air Zimbabwe by the Central Bank through the Parastatal Financial Support program, the airline continues to lose market share to competitor airlines, such as South African airlines which has 4flights daily into Zimbabwe. Emirates, Ethiopian and British airways are some of the airlines plying viable routes into Zimbabwe. In pursuance of the Strategy to Restore Viability the airline embarked on a route rationalization program with routes such as Harare/ Nairobi/ Dares Salaam, Harare/ Kariba, Harare/ Singapore/ Guangzhou, Harare/ Masvingo/ Buffalo Range, Harare/ Lilongwe, Harare/ Kinshasa, Harare/Dubai and the Democratic Republic of Congo internal operations, which failed to achieve the required critical mass of passengers to justify economic existence, being terminated in 2008 (Air Zimbabwe Holdings Survival Strategy: 2009).

3.3. Corporate Failures in Zimbabwe

- Several companies in Zimbabwe have faced difficulties associated with board failure and this has resulted in most of them winding up, while others have failed in improve viability. Of note are companies like Air Zimbabwe, PSMAS, ZBC, African Renaissance Bank (AFRE), BCCI, United Merchant Bank, ENG Capital and Barbican Bank. The major causes of corporate scandals were centered on poor oversight and lack of proper monitoring of the CEO and executive directors by the board leading to corporate governance breaches. While board structures were in place in the organizations, the board of directors had the biggest share of the blame for its failure to monitor management. Due to the widespread and the seemingly never – ending spectra of scandals, the Zimbabwean Government notes with concern the plethora of scandals and company failures bedeviling the country and affecting the people and the economy at large. This has led to the proposal to form a parliamentary committee to deal with corruption, scandals and misdemeanors perpetrated by those in fiduciary positions (The Herald of 3 March of 2014). To buttress efforts by government, the Institute of Chartered secretaries and Administrators in Zimbabwe (ICSAZ) has started promoting good corporate governance by hosting corporate governance awards called “Excellence in Corporate Governance Award” and “The Chartered Secretary of the Year award”. These efforts seek to promote corporate governance and effective board practices in Zimbabwe.Corporate governance codes seem not to be the panacea to board failure. Answers are needed as this creates a research agenda especially for Africa, and particularly Zimbabwe where boards are failing to rein in errant executives. The absence of a corporate governance code in Zimbabwe, 36 years after political independence is worrying. Action is needed sooner than later. Research agendas should focus on improving corporate governance practices and push for the publication of a code which is relevant to a developing country like Zimbabwe. This implies that boards should be strengthened and all processes that bring boards about should be strengthened and more Zimbabwean specific research on board operations should be escalated. The “old schoolboy” concept where board members are drawn from friends and former classmates is detrimental to proper oversight. Such board members protect CEOs rather than oversee their performances. There is need to establish how directors are selected in light of the high rate of company and board failures. Even where there are codes of good corporate governance practices, boards are failing and there is scope to find out why and proffer lasting solutions so that boards perform their oversight role with undoubted expertise.The research made use of the case of Air Zimbabwe to analyse the impact of corporate governance failure of SOEs in Zimbabwe. The research was prompted by the poor performance of SOEs in Zimbabwe where most have been receiving bailouts from Treasury year in year out with no positive results to show for it. This poor performance cuts across almost all SOEs and their continued reliance on the taxpayers’ money is not sustainable, given that SOEs are supposed to be self-sustaining institutions which must operate profitably and declare profits to the government as the sole shareholder. The poor performance of SOEs in Zimbabwe and Air Zimbabwe in particular has left a significant dent in the public confidence with SOEs. Air Zimbabwe was not spared from the effects and has seen skill flights and a sharp decline in the profitability, having to be bailed out by the Treasury for successive years without any changes in fortunes. In case of Air Zimbabwe, Board changes have been effected on political grounds and the frequency of the changes have resulted in lack of continuity in terms of Board work for successive Boards. The literature for this research was obtained from various sources.

4. Theoretical Framework

- Corporate governance can be broadly defined as the system by which companies are directed and controlled (Cadbury, 1992). Corporate governance is about rules and values that the board of a company set for the day to day running of that company. Contemporary debate on the subject has been dominated by the agency theory. The shareholders being the stewards of the company and the management are the agents. As far back as Adam Smith, it has been recognized that managers do not always act in the best interests of equity holders (Henderson, 1986). Corporate governance is also defined as a system by which businesses are managed by different participants in the corporation, such as the board, managers, shareholders and other stakeholders. However, we find that corporate governance is expected in every business entity, be it private or public for the business venture to be run in an ethical manner. To illuminate the above definitions, The Kings Report 3 (The King Committee 2009) advises that there are several accepted principles of good corporate governance that are applicable to both the private and public sector. The principles include discipline, transparency, independence, accountability, responsibility, fairness and social responsibility, among others. On the nature of corporate governance, Edwards and Clough (2005), rightly observe that it depends on economic, regulatory, fiscal, institutional and, judicial structures qualities and are influenced by a given country’s political situation. They add that autocratic political systems will tend to be intolerant of competition, transparency and accountability, and these will affect financial development. There has been a recent demand for theories that present a more positive view of managers and organizations (Donaldson, 2005). In this vein, Donaldson and Davis (1991 & 1993) rethought the corporate governance issue by challenging the prevailing assumptions of human motivation that derived from Agency Theory. These authors developed Stewardship Theory, a new perspective to understand the existing relationships between ownership and the management of the company. Over the last two decades, several contributions have confronted the opposing views of Stewardship Theory and Agency Theory. Empirical studies have attempted to validate the two different theories as a “one best way” to corporate governance, assuming either one model or the other (Davis et al., 1997). Nevertheless, the challenge lies in blending the best of both models and furthering conceptual advance (Hambrick, 2005).While Air Zimbabwe does not have a specific corporate governance policy, the government in 2010 recognised that this was one of the problems afflicting all SOEs or State Enterprises and Parastatals (SEPs). In response to this gap that was attributed for the failures of enterprises such as Air Zimbabwe, the government adopted a Corporate Governance Framework (CGF) to serve as a guide for the SEPs. The policy document states that in adopting this CGF, the Government intends to: Provide for a code of governance that will foster a culture of observance and adherence to regional and international best practices in organisational governance. The Corporate Governance Framework (CGF) provides Government, SEPs and stakeholders with a common frame of reference on corporate governance issues. The fundamental objective of this CGF is to promote the efficient use of public resources and to require accountability for the stewardship of those resources. (CGF Policy Document, 2010: xvi).The formulation of this CGF was based on the four “pillars” of corporate governance (responsibility, accountability, fairness and transparency [RAFT]). Guided by these pillars the framework outlines the following key principles that are expected to guide all state enterprises: form the bedrock of global best practice: ·the supremacy of the shareholder interest. Boards of Directors and managers should be, first and foremost, the custodians of the shareholders’ interest; ·The provision of adequate authority, responsibility and competencies to Boards and management for effective accomplishment of their functions and tasks; The clear separation of powers between the Board and the management for accountability and transparency purposes; ·The institution of clear reporting and compliance procedures and internal and external monitoring and evaluation frameworks; The need for good corporate citizenship which extends corporate responsibility beyond the need to only create profits for shareholders, but to the concerns of stakeholders regarding corporate, social and environmental responsibility (the triple bottom-line).

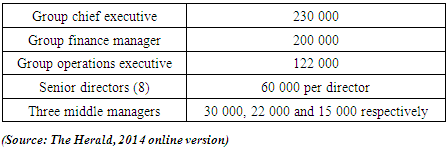

4.1. Remuneration for Board of Directors

- The main issue concerning directors’ remuneration is how best a company can manage to lure the executive in rewarding him or her highly contingent, long-term incentive related contract as a way to influence behaviour and align management interest with those of shareholders (Aivazian, 2005). The components or elements of executive remuneration might be basic salary, personal pension, bonus tied perhaps with annual performance of the company, other perks like health insurance and holiday allowances. Other long-term perks might include share options, company share and in some instances a severance pay where the company is committed to giving the individual a minimum severance pay if he or she is forced to leave the company (Coyle, 2003). Measures should therefore, be taken to prevent a senior executive remuneration spiraling beyond the capacity of the organization. The other way to go around unrealistic remuneration for executives is to employ performance based contracts so that one is only paid to what he or she has actually performed. In the case of Zimbabwe, the salaries and allowances which the parastatal bosses awarded themselves did not relate to the performance of their companies. Most of these companies are reeling under a heavy debt burden and workers could go for months without receiving their meager salaries, yet the bosses received hefty packages. Using these factors as yardsticks, it is clear that greediness has its fair share in the crumbling of the once vibrant parastatals. As of December 31 2013, the Premier Service Medical Aid Society (PSMAS) then led by Cuthbert Dube had a debt totalling US$38 million, which was supposed to be paid to service providers for medical services provided to its members. This was against the backdrop that the top management earned sky high salaries. The situation was not ideal for an organization that provides health services for more than 600 000 people, the majority of whom are government workers (The Herald, 2014). The table below summarizes what the top management at PSMAS got despite the challenges facing the company and the country at large.

|

5. Research Questions

- In view of the literature on SOEs in other countries and in Zimbabwe, this study seeks to inquire into the following:RQ1: To what extent has Air Zimbabwe complied with corporate governance principles?RQ2: What challenges are affecting the implementation of corporate governance principles?RQ3: What recommendations can Air Zimbabwe adopt to improve its corporate governance framework?

6. Research Design

- This study combined the strength of qualitative and quantitative research designs. As a result, there was triangulation of methods in data collection and analysis. Gratton and Jones (2010) advise that a sample is a subset of a population carefully chosen for research purposes. The first sampling consideration was the selection of Air Zimbabwe as a case study to inquire into the problem of the study. Yin (2003) defines a case study as a scientific inquiry that investigates a problem within its context. There are many SOEs in Zimbabwe and an inquiry based on all the enterprises would present a more general overview in terms of findings. The study selected a single case study, Air Zimbabwe, because it allows for detailed inquiry and the findings from such a study will create in-depth knowledge which can also be generalised to other similar cases. This study was based on a sample size of 60 respondents. The board will be allocated 20% of the questionnaire copies whilst management and employees will be allocated 80%. This was after considering the ratio between Board Staff and management as well as employees of the company. Self-administered structured questionnaires were used to gather data from the selected sample. Interviews were also conducted with key managers in order to gather detailed information and explanations which could not be provided in the questionnaire. Documentary search was also used to triangulate the data gathered from other instruments. The data from the questionnaire was analysed using the statistical package, Microsoft Excel.

7. Findings

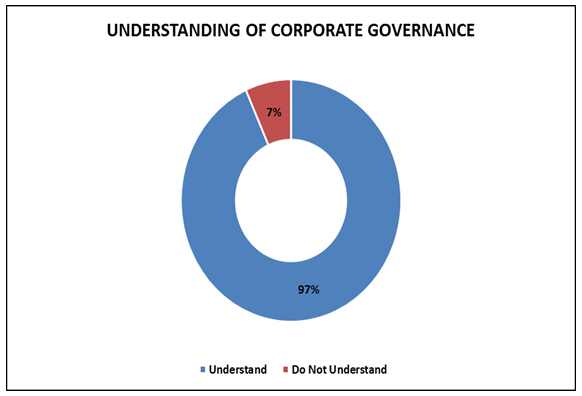

7.1. Understanding of Corporate Governance

- In inquiring the extent to which Air Zimbabwe was complying with the tenets of corporate governance, it was first important to understand the levels of understanding among the board members. The results are summarised below.

| Figure 1. Board members appreciation of corporate governance |

7.2. Lack of Continuity in Boards

- At the time of conducting this study, almost all members 87% were on the Board for less than 2 years of the stipulated 3-year term. The major reason cited was political interference in terms of Board appointments. The change of the Cabinet Minister responsible for transport meant wholesale changes to the Board as the new Minister had to bring in a new Board aligned to him/her. As a result, the Board faced continuity problems especially considering that the company follows five year strategic plans, implying that a new Board may not support a previously crafted business plan to turnaround the company. One member summed it up by saying, ‘....I served 2 years out of a 3 year Board Term. A change/reshuffle of Government Ministers had most Parastatal or Quasi Government Boards suspended, replaced or dismissed. There is no continuity between Boards and the appointees are clueless of Airline Operations”.

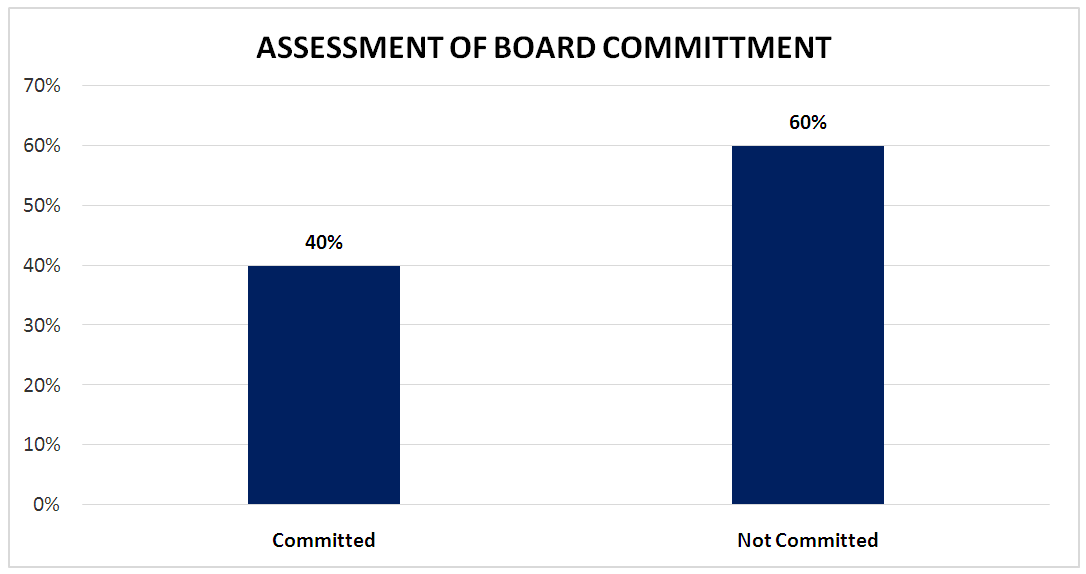

7.3. Lack of Commitment to Board Work

- The study investigated the performance of the board based on the assessment by the board members and the results are shown below.

| Figure 2. Board members assessment of commitment to operations |

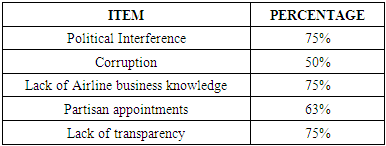

7.4. Challenges Affecting the Implementation of Corporate Governance Principles

- All the interviewees agreed that management faces serious challenges when implementing CG strategies. The most familiar challenges were limited financial resources, political interference, corruption, partisan appointments and lack of airline business for most Board members. Another problem was lack of shared view amongst the responsible Ministry, Board, Management and Employees. One member summed it up when he said, “Management no longer reports to the Board, instead we report to the Permanent Secretary and then brief the Chairman. Since all these challenges began, the Board has never sat. We have grounded all our fleet because of various challenges but up to now the Board has not said anything, the only option is to report to the parent ministry”. These findings reveal a glaring gap between management and the Board, yet the Board is supposed to provide strategic direction to the company. The respondents were asked to affirm or deny whether political interference, corruption, lack of airline business knowledge, partisan appointments and lack of transparency were challenges in the implementation of strategies. The results are summarised in the table below.

|

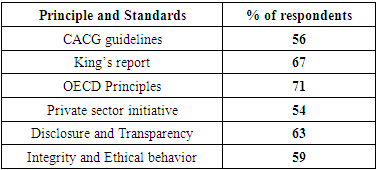

7.4.1. Principles, Standards and Practices for Corporate Governance

|

7.5. Commitment to Corporate Governance (CG)

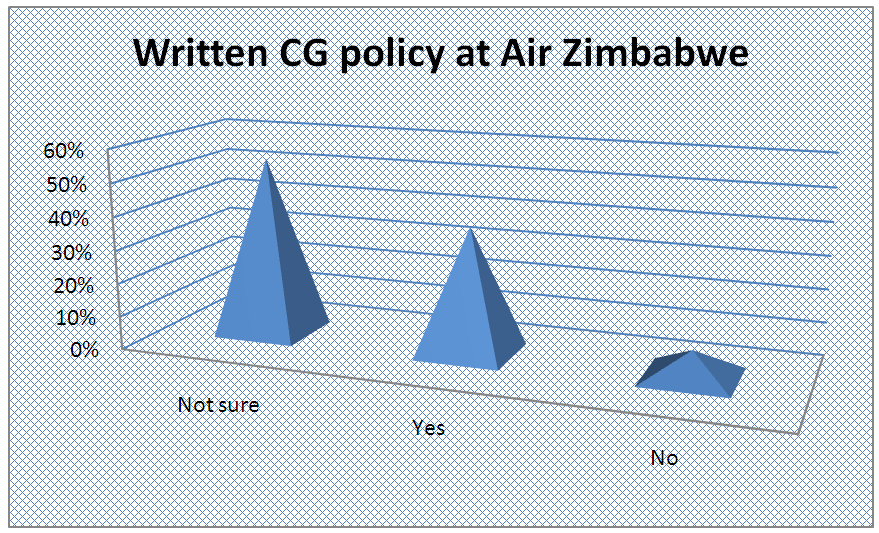

7.5.1. Availability of Written Corporate Governance Policy

- Majority (54%) of the respondents held that they were not sure if there was any written Corporate Governance policy at Air Zimbabwe, 38% said there is a written Corporate Governance policy whereas an insignificant 8% suggested that there is no written Corporate Governance in their organisation. The results entails that most of the respondents are not sure of the availability of any corporate governance policy in their organisation. The purpose of the policy is to demonstrate the organisation’s commitment to sound corporate governance and to document how governance is communicated within the organisation. The desired result is effective governance within the organisation and in turn enhanced organisational performance. Better understanding and management of risks minimise the negative aspects and maximise the opportunities. It also allows the organisation to demonstrate how it is discharging legal, sector and ethical obligations and provides a mechanism for benchmarking accountability and assists in the prevention and detection of fraudulent, dishonest and/or unethical behaviour. A corporate governance policy in an organisation would ensure a good corporate governance framework. It also sets out the structure through which the division of power in the organisation is determined. However, given the importance of a corporate governance policy in an organisation, the results may entail that the organisation may not be having a written corporate governance policy as it is not known to the whole organisation. This therefore means that those respondents who suggested that there were not sure of the availability or presence of a Corporate Governance policy at their organisation may be implying that it may not be present at their organisation.

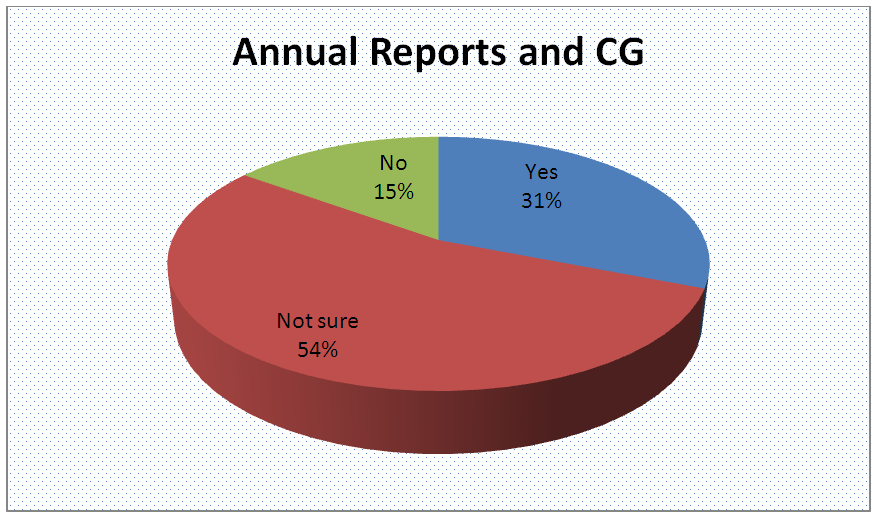

7.5.2. Annual Reports and Corporate Governance

- This sought to establish if the annual reports of the company outline the steps of improving corporate governance in the organisation. Majority (54%) of the respondents were not sure if the annual reports provide steps of improving CG, 31% concurred that the annual reports provides steps whereas 15% were of a conflicting view.

| Figure 3. Written CG policy at Air Zimbabwe |

| Figure 4. Annual reports and CG |

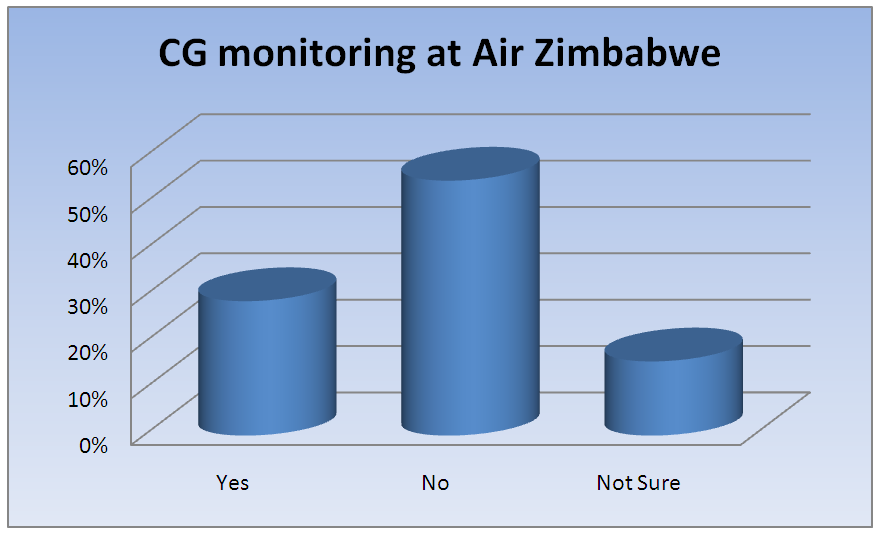

7.5.3. CG Policy Monitoring

- The results in figure 5 shows that the majority (55%) concurred that there is no identified officer responsible for ensuring compliance with CG, 29% said there is an officer responsible for that whereas 16% were not sure. The results show that Air Zimbabwe does not have a dedicated office or individual to enforce and monitor CG compliance. The poor level of the company’s commitment to CG principles and practices was shown in the non-availability of an officer whose responsibility would be to ensure that the organisation adhered to the corporate governance principles. In light of the findings, it could be noted that most of the respondents did not understand the duties of a company secretary or rather, the company secretaries were not advocating for good corporate governance.

| Figure 5. CG monitoring at Air Zimbabwe |

7.6. Code of Ethics

- All of the respondents concurred that they have a code of ethics in their organisations. This shows that Air Zimbabwe does have a code of ethics. Whilst some respondents said Air Zimbabwe has a code of ethics in place the main challenge comes in making the employees aware of the code of ethics. Recent events in corporate America have demonstrated the destructive effects that occur when the leadership of a company does not behave ethically. Business ethics if properly interpreted means the standards of conduct of individual business people, not necessarily the standards of business as a whole. The best example is Enron, which was the financial markets golden child for some time until it was discovered that they were not doing their books in a proper manner. Enron quickly became the financial market's scapegoat and easy fodder for business ethics case studies. Enron's example highlights the importance of having a company code of ethics.

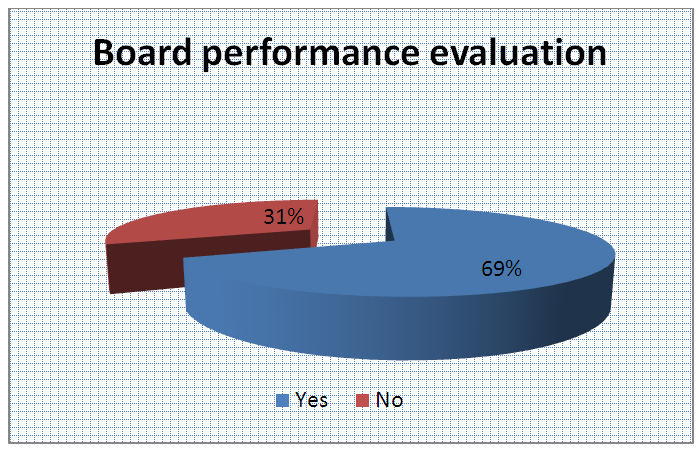

7.6.1. Board Performance Evaluation

- From the results, the board at Air Zimbabwe does not have a mechanism to evaluate its own performance as shown by the majority (69%) whereas 31% were of a different view. Such a mechanism is critical in that the board will be able to see if it is really performing to its expectations and to appreciate the areas where there are gaps in its performance. Performance measurement enhances the effectiveness of the directors and thus further reduces the risk to the organisation. The obligation to have an annual formal evaluation ensures that the board takes time to evaluate its own performance. The primary purpose is to enhance not only the performance, effectiveness and contribution of each director, but also to improve the effectiveness of the board as a whole in fulfilling its role. Formal evaluation once a year should not replace informal feedback on performance on an ongoing basis, although establishing a formal evaluation methodology provides an objective framework for analytical feedback to the Board members for the appointment processes. The results point to a situation of poor CG practices since Board members who are not performing are kept by the company and this can lead to lack of oversight on executive management.

| Figure 6. Board performance evaluation |

| Figure 7. Disclosures of reports |

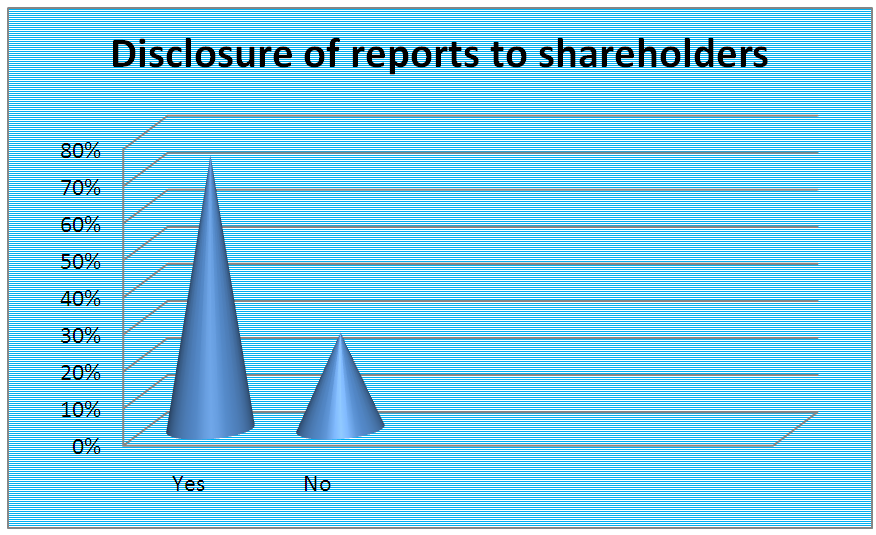

7.6.2. Disclosure of Reports

- According to the findings, regular and adequate reports are not made available on time to shareholders by (74%) of the respondents whereas 26% were of a different viewpoint. From the results, it can be said that the shareholders do not get regular and adequate disclosure reports on time. The corporate governance framework should ensure timely and accurate disclosure on all material matters, including financial situation, performance, ownership and governance of the company. The disclosures should at minimum be annually, or even semi-annually or quarterly, or more frequently for material developments. Material information is that information whose omission or misstatement could influence economic decisions taken by users of information. The disclosure of information should be simultaneous to all shareholders. Requirements should not create unreasonable administrative or cost burdens. Strong transparent disclosure regime is pivotal for market-based monitoring of companies and central to shareholder ability to exercise ownership rights. Disclosure can be a powerful tool for influencing companies and protecting investors.

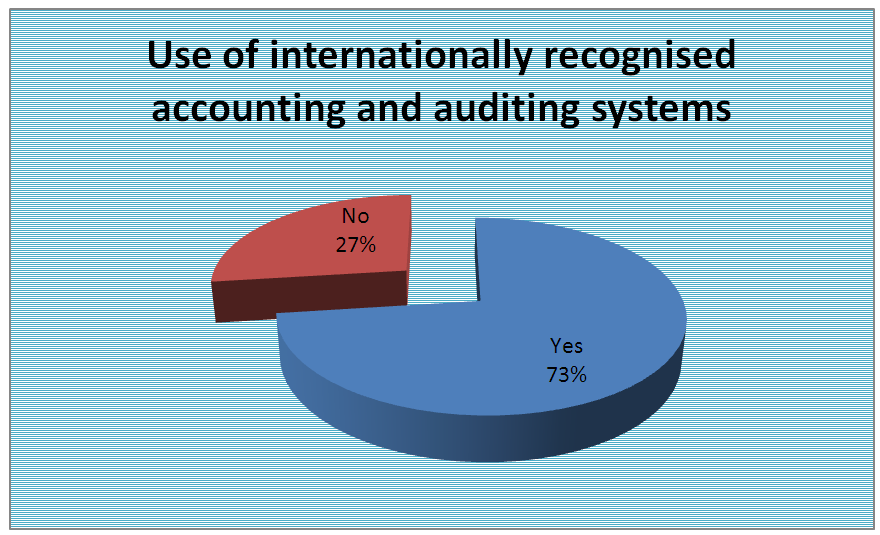

7.6.3. Transparency and Disclosure

- According to the findings in figure 8 below the company uses internationally recognised accounting and auditing systems. However, as a former British colony, Zimbabwe adapted UK-based accounting systems on gaining independence, thus follows a disclosure-based regime. The Companies Act (Chapter 24:03) is the main statute governing corporate reporting in Zimbabwe. The ICAZ monitors corporate reporting compliance in Zimbabwe. Like the US Securities and Exchange Commission, the ICAZ employs a review method in monitoring and enforcing compliance with statutory and regulatory disclosure requirements. However, in light of the above the Audit Office and most of the companies in Zimbabwe adopt the internationally recognised accounting and auditing systems, including Air Zimbabwe.

| Figure 8. Use of Internationally Recognised Accounting and Auditing Systems |

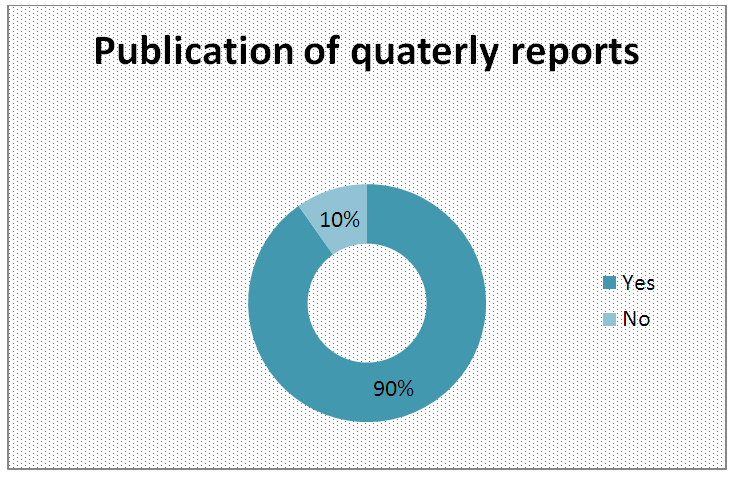

| Figure 9. Publication of quarterly reports |

7.6.4. Publication of Quarterly Reports

- From the study findings in figure, 4.10 Air Zimbabwe does not report meaningful quarterly reports and this presents a challenge on disclosure and transparency. The quarterly reports are the principal ways in which the directors are accountable to the shareholders. This will aid in financial decisions by the shareholders, as they will be aware of the financial position of the company. This therefore brought about the need for the quarterly reports to be meaningful so that they are understandable to the shareholders, as they would want to make sense out of them. A meaningful quarterly report in line with the IAS would enhance confidence in the shareholders and prospective investors and hence the company would attract new investments. Quarterly reports are an important tool for enhancing corporate governance. This publishing of quarterly reports is also a step towards achieving accountability and transparency.

8. Discussion

- Glassman (2002) states that governance matters, good governance tends to channel corporate decisions in the right directions and conversely bad governance leads bad decisions. The major advantages of good corporate governance lie in the increased ability of properly governed companies to attract institutional and foreign investment, to implement sustainable growth. It also lies in the ability to identify and manage their business and other risks within predetermined parameters, thereby limiting their potential liability. In the contest for scarce skills and human talent, properly governed companies with a reputation for being good corporate citizens are also more easily able to attract better caliber employees.

8.1. Access to Capital

- The inability to access capital at competitive rates remains a major inhibitor to the growth of many public and private companies’ developing countries. Corporate governance may have been regarded as a minor issue, but the quality of a company’s corporate governance is now ranked alongside its returns on investment ratios in determining whether potential investors will invest in a company. Outstanding financial performance at any cost is no longer the sole consideration when making investment decisions. According to Mckinsey investor opinion survey (2000), more than 84% of global institutional investors indicated a willingness to pay a premium ranging between 18% and 27% for shares of a well-governed company over one considered poorly governed, albeit with a comparable financial record. For companies to be able to attract investors, it is mandatory to ensure that a sound corporate governance framework exists. This is equally important for SOEs since governments may require some investing partnerships given the difficulty in continuously bailing out loss making SOEs.

8.2. Foreign Direct Investment

- According to Dube (2003), a country’s reputation regarding governance issues is a collage of its legal and regulatory approach to corporate governance and the conduct of the individual players in the economy. According to Manuel (2006) a study conducted at the Stanford law school showed that institutions looking to invest money in emerging economies were more likely to invest money in companies that had sound corporate governance practices. Conventional governance wisdom has it that well governed countries and companies are able to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) since they are categorized as an acceptable investment risk. Good corporate governance and reduced levels of corruption should not be seen as a guarantee that foreign investment will promote economic development in Africa. For as long as African countries are not embracing transparency and good governance, the only countries that are likely to prefer Africa as an investment destination are those with an interest in exploiting continent’s resources.

8.3. Public Demand for Accountability

- Public interest in corporate governance has heightened with the proliferation, in the last decade, of high-profile corporate frauds resulting in huge losses. The list of corporate governance failures in the last decade from AIG and Citi-group to Enron, WorldCom and Xerox reads like an alphabetical checklist. Companies took decades to build and had to be nationalized or bailed out by government loans. Schmidt (2003) argues that in a bull market, the approach of investors is normally far more laissez-faire, with the soothing sounds of share prices constantly ticking upwards tending to lull investors into worrying less about the management of their investments and the integrity of a company’s directors. Schmidt (2003) however, adds that in tough economic times, investors and the public tend to keep a more watchful eye on the way companies are being run. They tend to demand greater accountability and better corporate citizenship from companies.

8.4. Corporate Governance and Monitoring State-owned Enterprises

- In many African countries, the capacity to support the implementation of good corporate governance is undermined by the existence of weak monitoring and watchdog organizations. Government ministries responsible for actively monitoring state-owned enterprise boards, and other mechanisms such as independent regulators, do not fulfil their role as overseers. “Many are generally weak and subject to external influence by politicians. Community watchdog organizations such as consumer bodies are not well developed in Africa” (Botha, 2001). Estrin (2002) put forward that even if a state-owned firm operates in a competitive market and the government tries to enforce an objective of profit maximization on its management but if problems of corporate governance are not solved, there still would be poor performance.

8.5. Political Interference as a Stumbling Block to Effectiveness of Air Zimbabwe

- Political interference was noted as one of the major problems that impede the enforcement of corporate governance. It was found that because of nepotism and corruption, the airline sometimes employ people who may not have the right qualification but because of their associations they may find themselves working in Air Zimbabwe’s specialised areas. On that note Air Zimbabwe is not complying with principles of corporate governance. There is lack of transparency also between the steward and the agency and this resulted in poor performance. Failure to communicate properly and appreciate the other side’s priorities diverge the thrust of corporate governance.According to the theory of Stewardship, the government being the steward, there is no one being held accountable because the government represent the general populace as shareholders. Naturally it is very difficult for these people to have a say on the under performance of the SOE. According to the Chinese socialist system of managing SOEs, the government would ensure that the SOE performs, as that would also enable growth of the enterprise as well as bring revenue to the government. The government and the legal person both have interest to see profitability of the SOE. The case of Zimbabwe is lack of accountability and failure to enforce corporate governance. This is exacerbated by failure by the government as the steward to listen to the agent (management) on the ground. Negative political interference makes difficult for parastatals to work independently and effectively. It should be borne in mind that SOEs are there to generate income as well as provide services to the nation. The Chinese socialist system proved to be effective; because the monitoring system would be alive through the legal person as well as the government. Enforcement of corporate governance proved to be difficult for the Zimbabwe SOEs, so the structures of the SOEs may need to be revisited in view of creating shareholding structures which can give positive results. Investors are persons whose focus is on economic growth and profitability, so for Zimbabwe to attract investors there is need to enforce corporate governance or borrow the Chinese socialist style of running SOEs. The focus of the government should be on achieving profitability in SOEs.

9. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study has revealed grey areas in as far as CG is practiced and implemented in developing country such as Zimbabwe. Whist the study specifically focused on State Owned Enterprises in Zimbabwe, it would be more profitable and ideal if a similar study could be conducted using a sector specific approach in the private sector. This would provide a holistic picture on CG matters in the country and will assist the government in crafting a legal framework to guide CG implementation. This is important since a sound corporate governance environment has the potential to attract foreign capital for the economic development of the country. Board changes are a ministerial prerogative and as such, viability problems being faced by Air Zimbabwe can be interpreted within the context of political interference and lack of commitment, common vision within the Board , management and a glaring non- compliance with corporate governance principles. Corporate governance is important in any organisation as it enhances accountability and transparency. Good CG is expected to enhance shareholder and prospective shareholders /investors’ confidence. The majority of the respondents (79%) were of the view that corporate governance attracts long term foreign capital, broaden and deepens local capital markets by attracting local investments. About 73% indicated that it was a source of competitive advantage and is critical to economic advancement. At Air Zimbabwe, both management and the Board do not attach importance to CG as there is no written CG Policy. Half of the interviewees (60%) said there is no commitment to Board work because of frustration by most members. Examples of high corporate fraud scandals being perpetrated by some Board members were cited as major reason why other members were not committed. The challenges of corporate governance faced at Air Zimbabwe were regulatory framework, unethical business practices, limited human resources capabilities and political interference. These were posing problems in the implementation of good corporate governance practices. Seventy five percent (75%) cited the political interference as a major problem; another 75% indicated that the major challenge lack of Airline business knowledge, lack of transparency (75%), corruption (50%), and partisan appointments. Air Zimbabwe also faces lack of shared vision amongst the responsible Ministry, Board, Management and Employees.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Sincere acknowledgments go to the Almighty God. Special thanks are also due to Simon Matingwina, Matthew Mushininga and Felistus Tahwa-Magama and Richard Mutunduwe for their valuable contributions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML