-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2017; 7(6): 194-201

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20170706.02

Corporate Governance in Cape Verdean Banks: A Theoretical Review

Yunhong Hao1, Ailton Gomes Moreira2, Subhani Hafiz Inayat Ul Haq2

1Dean of the School of Business Administration, Zhejiang Gongshang University, Hangzhou, China

2School of Business Administration, Zhejiang Gongshang University, Hangzhou, China

Correspondence to: Ailton Gomes Moreira, School of Business Administration, Zhejiang Gongshang University, Hangzhou, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Cape Verdean banking sector had seen some corporate difficulties in the past, specially concerning to non-performing loans, which principally resulted due to lack of a robust corporate governance structure. This study provides a theoretical framework and a model for understanding the concept of corporate governance rather than empirical views. This was achieved by delineating the historical overview of corporate governance, theory of corporate governance, principles and benefits of corporate governance, mechanisms of corporate governance and the legal frameworks. The study concludes that the key setback to corporate governance in Cape Verdean banking sector is non-existence of the code of corporate governance practices as well as the non-existence of the institute for corporate governance in Cape Verde.

Keywords: Corporate Governance, Bank, Agency, Stakeholder, Stewardship Theory, Mechanisms, Model

Cite this paper: Yunhong Hao, Ailton Gomes Moreira, Subhani Hafiz Inayat Ul Haq, Corporate Governance in Cape Verdean Banks: A Theoretical Review, Management, Vol. 7 No. 6, 2017, pp. 194-201. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20170706.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the study

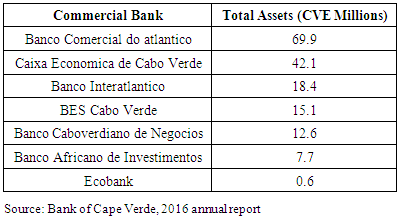

- The issue of corporate governance has become a popular discussion topic in developed and developing countries. The way in which corporate governance is organized differs between countries, depending on the economic, political, legal and social contexts. However, firms that operate in developing countries such as Cape Verde may be affected by economic instability resulting in severe economic dislocation and sharp escalation in public expenditure, which result in a widening fiscal deficit. In Cape Verde, apart from weak regulatory and institutional frameworks, increasing public debt, high unemployment rates have been growing macroeconomic problems that were further worsened by the 2008 global finance crisis, which in turn affected the performance of firms. The efforts to strengthen corporate governance in banks will boost public confidence and ensure efficient and effective functioning of the banking system (Soludo, 2004a). According to Heidi and Marleen (2003:4), banking supervision cannot function well if sound corporate governance is not in place. Consequently, banking supervisors have strong interest in ensuring that there is effective corporate governance at every banking organization. As opined by Mayes, Halme and Aarno (2001), changes in bank ownership during the 1990s and early 2000s substantially altered governance of the world’s banking organization. It is therefore necessary to point out that the concept of corporate governance of banks and very large firms have been a priority on the policy agenda in developed market economies for over a decade, and now from Cape Verde. Further to that, the concept is gradually warming itself as a priority in the African continent. Indeed, it is believed that the financial crisis and the relative poor performance of the corporate sector in Africa have made the issue of corporate governance a catchphrase in the development debate (Berglof and Von -Thadden, 1999). What is corporate Governance?Rezaee (2009) describes corporate governance as an ongoing process of managing, controlling and assessing business affairs to create shareholder value and protect the interests of other stakeholders. Corporate governance therefore refers to the processes and structures by which the business and affairs of institutions are directed and managed, to improve long-term shareholders’ value by enhancing corporate performance and accountability, while considering the interest of other stakeholders (Jenkinson and Mayer, 1992). Corporate governance is therefore, about building credibility, ensuring transparency and accountability as well as maintaining an effective channel of information disclosure that will foster good corporate performance. Solomon (2010, p. 6) defines corporate governance as ‘the system of checks and balance, both internal and external to companies, which ensure that companies discharge their accountability to all their stakeholders and act in a socially responsible way in all areas of their business activity’. The aim of corporate governance is to facilitate the efficient use of resources by reducing fraud and mismanagement with the view not only to maximize, but also to align the often-conflicting interests of all stakeholders (Cadbury, 1999; King Report, 2002). The OECD (2004, p. 11) defines corporate governance as: ‘Corporate governance involves a set of relationships between a company’s management, its board, its shareholders and other stakeholders’. The corporate governance structure specifies the distribution of rights and responsibilities among different participants in the corporation, such as the board, managers, shareholders and other stakeholders, and spells out the rules and procedures for making decisions on corporate affairs. By doing this, it also provides the structure through which the company objectives are set and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance (OECD, 1999). In this case, the company is considered a social entity that has accountability and responsibility to a variety of stakeholders, encompassing shareholders, creditors, suppliers, customers, employees, management, government and the local community (Freeman & Reed, 1983; West, 2006; Mallin, 2007).

| Figure 1. Corporate Governance |

2. Corporate Governance, an Historical Overview

- Over centuries, corporate governance systems have evolved, often in response to corporate failures or systemic crises. There has been no shortage of other crises, such as the secondary banking crisis of the 1970s in the United Kingdom, the U.S. savings and loan debacle of the 1980s, East- Asian economic and financial crisis in the second half of 1990s (Flannery, 1996). In addition to these crises, the history of corporate governance has also been punctuated by a series of well-known company failures: the Maxwell Group raid on the pension fund of the Mirror Group of newspapers, the collapse of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, Baring Bank and in recent times global corporations like Enron, WorldCom, Parmalat, Global Crossing and the international accountants, Andersen (La Porta, Lopez and Shleifer 1999). These were blamed on a lack of business ethics, shady accountancy practices and weak regulations. They were a wake- up call for developing countries on corporate governance. Most of these crisis or major corporate failure, which was a result of incompetence, fraud, and abuse, was met by new elements of an improved system of corporate governance (Iskander and Chamlou, 2000).

3. Principles and Benefits of Corporate Governance

- The principles of corporate governance have been developed as guidelines rather than rules which could be used across different countries and markets (Gul & Tsui 2004b). The Cadbury Code (1992) emerged because of the corporate failures of the 1980s. It recommended changes to the board structures and procedures to make the firm more accountable to the shareholders, suggesting an increase in the number of independent directors on the board, separation of the chairman and CEO, and introduction of board committees (Chowdary 2002). OECD principles of corporate governance (1999) revised in 2004 were intended to assist governments in their effort to evaluate and improve legal, institutional and regulatory framework for corporate governance in their countries. The OECD principles relate to equitable treatment, responsibility, transparency and OECD principles states: Principles focus on governance problems that result from the separation of ownership and control. The degree to which corporations observe basic principles of good corporate governance is an increasingly important factor for investment decisions. Of particular relevance is the relation between corporate governance practices and the increasingly international character of investment. (OECD 2004, pp. 12-3) In 2006, the OECD issued the methodology for assessing the implementation of the OECD principles on corporate governance. It states: ...to ensure the basis for an effective corporate governance, the framework should promote transparent and efficient markets, be consistent with the rule of law and clearly articulate the division of responsibilities among different supervisory, regulatory and enforcement authorities. (OECD 2006, p. 27). These principles were adopted by the International Corporate Governance Network (ICGN), which was founded in March 1995, for their members to consider when making investment decisions. The effectiveness of corporate governance depends on the application of these principles in a manner which benefits stakeholders, as well as broader industries and economic sectors. Benefits to stakeholders include resolving conflicts of interest, instilling controls and a sense of ethics, and enforcing and encouraging transparency.

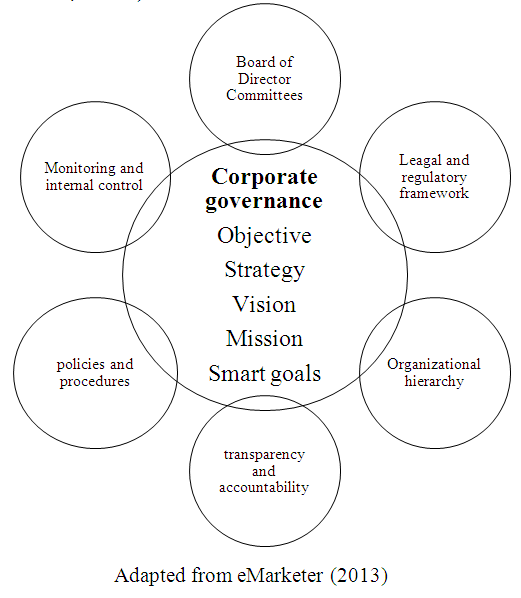

4. Theoretical Perspective for Corporate Governance

- Several diverse fundamental theories underline corporate governance, including the original agency theory, stewardship theory, stakeholder theory, resource dependency theory, transaction cost theory and political theory (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009). However, most discussions on corporate governance theories have focused on the shareholder and the stakeholder perspective (Letza, Sun & Kirkbride, 2004; Szwajkowski, 2000; Vinten, 2001).

4.1. Agency theory

- Stephen Ross and Barry Mitnick are the first scholars to propose and begin the agency theory, according to Mitnick (2006). Stephen Ross is responsible for the origin of the economic theory of agency, and Barry Mitnick for the institutional theory of agency, though the basic concepts underlying these approaches are similar. Indeed, the approaches are complementary in their uses of similar concepts under different assumptions. In short, Ross introduced the study of agency in terms of problems of compensation contracting; agency was seen as an incentives problem. Mitnick introduced the now common insight that institutions form around agency, and evolve to deal with agency, in response to the essential imperfection of agency relationships: Behavior never occurs as it is preferred by the principal because it does not pay to make it perfect. But society creates institutions that attend to these imperfections, managing or buffering them, adapting to them, or becoming chronically distorted by them. Thus, to fully understand agency, we need both streams -- to see the incentives as well as the institutional structures.Jensen and Meckling (1976) described agency theory as a contract under which one or more persons (the principals) engage another person (the agent) to perform some service on their behalf, which involves delegating some decision-making authority to the agent. According to this theory, shareholders who are the owners of the corporation appoint managers or directors and delegate to them the authority to run the business for the corporation’s shareholders (Clarke, 2004). The agency relationship between two parties is defined as the contract between the owners (principals) and the managers or directors (agents) (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Based on the agency theory, shareholders expect the managers or directors to act and make decisions in the owners’ interests. However, managers or directors may not necessarily always make decisions in the best interests of the shareholders (Padilla, 2002). The separation of ownership and control produces an innate conflict between the shareholders (principals) and the management (agents) (Aguilera et al., 2008). This conflict of interest can also be exacerbated by ineffective management monitoring on the part of shareholders because of shareholders being dispersed and therefore unable, or lacking the incentive, to carry out necessary monitoring functions. Consequently, the managers of a company might be able to pursue their own objectives at the cost of shareholders (Hart, 1995). Thus, two problems involving the agency theory occur in the agency relationship. The first problem is that, because it is difficult or expensive for the principal to verify what the agent is doing, the principal cannot verify that the agent has behaved appropriately. The second problem is that, because of differing attitudes towards risk, the principal and the agent may favor different courses of action (Eisenhardt, 1989). Grant (2003) argues that the main purpose of shareholders (principals) is to maximize their value (interest), whereas the main purpose of agents is to expand and grow the corporation because success will reflect favorably on management. According to Hart (1995), a corporate governance issue occurs in an organization in the presence of two conditions. First, there is a conflict of interest or agency problem between members of the company. Second, the conflict of interest or agency problem cannot be dealt with through a contract. Hart observes that there are several reasons why contracting might not always be possible. It is impossible for a contract to cover all eventualities in relation to the firm. In addition, there are costs associated with negotiating contracts and enforcing them. Effective corporate governance can reduce agency costs and tackle problems related to the separation of ownership and control. It can be viewed as a set of mechanisms designed to reduce agency costs and protect shareholders from conflicts of interest with agents (Fama & Jensen, 1983a). The objective of corporate governance mechanisms, then, is to encourage management to make the same decisions that owners would have made themselves, such as investment in positive net present value (Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). From the perspective of the agency theory, corporate governance is viewed as a monitoring or control mechanism that is sufficient to protect shareholders from conflicts of interest with agents (Fama & Jensen, 1983b).

4.2. Stakeholder Theory

- One of the original advocates of stakeholder theory, Freeman (1984), identified the emergence of stakeholder groups as important elements to the organization requiring consideration. Freeman further suggests a re-engineering of theoretical perspectives that extends beyond the owner- manager-employee position and recognizes the numerous stakeholder groups. Freeman (1984: 234), suggests, if organizations want to be effective, they will pay attention to all and only those relationships that can affect or be affected by the achievement of the organization’s purpose. That is, stakeholder management is fundamentally a pragmatic concept. Regardless of the content of the purpose of the firm, the effective firm will manage the relationships that are important. Sundaram and Inkpen (2004a, p.352) also suggest that “stakeholder theory attempts to address the question of which groups of stakeholder deserve and require management’s attention”.Stakeholder theory offers a framework for determining the structure and operation of the firm that is cognizant of the myriad participants who seek multiple and sometimes diverging goals (Donaldson and Preston 1995). Nevertheless, Sundaram and Inkpen (2004a) posit that wide- ranging definitions of the stakeholder are problematic.

4.3. Stewardship Theory

- “A steward protects and maximizes shareholder’s wealth through firm performance, because, by so doing, the steward’s utility functions are maximized” (Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson, 1997:25 cited in Cullen, Kirwan and Brennan, 2006:13). The steward identifies greater utility accruing from satisfying organizational goals than through self- serving behavior. Stewardship theory recognizes the importance of structures that empower the steward, offering maximum autonomy built upon trust. This minimizes the cost of mechanisms aimed at monitoring and controlling behaviors (Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson, 1997). Daily et al. (2003) contend that to protect their reputations as expert decision makers, executives and directors are inclined to operate the firm in a manner that maximizes financial performance indicators, including shareholder returns, on the basis that the firm’s performance directly impacts perceptions of their individual performance. According to Fama (1980), in being effective stewards of their organization, executives and directors are also effectively managing their own careers. Muth and Donaldson (1998) described stewardship theory as an alternative to agency theory which offers opposing predictions about the structuring of effective boards. While most of the governance theories are economic and finance in nature, the stewardship theory is sociological and psychological in nature. The theory as identified by Sundara-Murthy and Lewis (2003) gives room for misappropriation of owners’ fund because of its board structure i.e. insiders and the chairman/CEO duality role.

| Figure 2. Theoretical perspective of Corporate Governance |

5. Governance Standards and Principles in the United States and in the United Kingdom

5.1. United States

- The discussion on corporate governance in the US began in 1932 with a book by Berle and Means (Hopt, 1994). Since then, the Business Roundtable has addressed corporate governance issues, including the Role and Composition of the Board of Directors of the Large Publicly Owned Corporation in 1978 and the Statement on Corporate Responsibility in 1981 (Business Roundtable, 1997). The Enron scandal prompted more attention to developing corporate governance as a response by the Centre of Corporate Governance (CCG) and the IIA Research Foundation. For instance, the Centre of Corporate Governance at Kennesaw State University aims to emphasize audit committees and entrepreneurial companies to improve effective corporate governance for public, private and non-profit enterprises (Centre of Corporate Governance and Kennesaw, 2002). The Center launched 10 principles: Interaction, Board Purpose, Board Responsibilities, Independence, Expertise, Meetings and Information, Leadership, Disclosure, Committees and Internal Audit (Hermanson & Rittenberg, 2003). In 2003, the Hon. Jed S. Rakoff of the US District Court for the Southern District released the ‘Restoring Trust’ report concerning WorldCom Inc. in November 2002. This report included 78 recommendations in 10 main areas: board of directors, board leadership and the chairman of the board, board compensation, executive compensation, audit committee, governance committee, compensation committee, risk management committee, general corporate issues, and legal and ethics programs (Breeden, 2003). In addition, the Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) Institute Centre for Financial Market Integrity set up the Asset Manager Code of Professional Conduct draft for industry debate and observation in 2004. The code was set up to extend the CFA Institute Code of Ethics and Standards of Professional Conduct to address individual conduct. This code is a guideline to managers globally and includes: Loyalty to Clients, Investment Process and Actions, Trading, Compliance and Support, Performance and Valuation, and Disclosures (CFA Institute Centre, 2004). In 2005, the NYSE set up the Proxy Working Group (PWG) to evaluate the voting and proxy process, including rules that allow brokers to vote on certain issues on behalf of the beneficial owners of shares. In 2006, the PWG report was published with recommendations to both the NYSE and the SEC to develop the proxy voting system. In 2007, the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association–College Retirement Equities Fund (TIAA–CREF) set up corporate governance policies. Its Statement of Policy inquired about: maintaining a culture of integrity; contributing to the strength and continuity of corporate leadership; guaranteeing board and management accountability; and encouraging the long-term growth and profitability of the business enterprise. In response to the financial crises of 2008 and 2009, the NYSE decided to support a comprehensive review of corporate governance principles that could be widely accepted and supported by issuers, investors, directors and other market participants and experts. In addition, the NYSE established the Commission on Corporate Governance in 2009 to debate fundamental topics of governance issues such as the proper role and scope of a director’s authority, management’s responsibility for governance, and the relationship between shareholders’ trading activities, voting decisions and governance. The diverse Commission members analyzed changes that had occurred over the past decade, their effect on how directors viewed their job, their relationship to management and shareholders, and how the current governance system generally worked (NYSE, 2010). In addition, the SEC and other regulators highlighted major issues that have appeared due to fundamental changes to the governance of corporations, with corporate governance becoming a prominent issue both in the financial markets and with the public. Four foundation governance principles, which could be widely accepted and support by issuers, investors, directors and other market participants and experts, were set up for discussion by the NYSE in 2010.

5.2. United Kingdom

- The development of corporate governance has attracted more attention in the UK since the series of corporate collapses and scandals in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including the BCCI bank and Robert Maxwell pension funds (Financial Reporting Council (FRC), 2006; Jones & Pollitt, 2001). Thus, the Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance, chaired by Sir Adrian Cadbury, was set up in 1992 (Cadbury Report, 1992). This Committee evaluated the effectiveness of audits and was to consider the relationship between shareholders, directors and auditors by investigating the structure and responsibilities of the boards of directors (Rayton & Cheng, 2004). Corporate scandals such as Enron and WorldCom in the US revealed some difficulties in the corporate governance system in the US, which led to concern about the system of corporate governance in the UK (FRC, 2006). Therefore, the Smith Committee was formed and chaired by Sir Robert Smith in 2002. The main aim of the Smith Committee was to review the effectiveness of audit committees. In 2004, the Turnbull Review Group was formed by the FRC to investigate the effect of guidance and linked disclosures and to determine whether the guidance needed to be enhanced. The new revision was established in 2005 to support directors to evaluate how their companies had implemented the requirements of the Combined Code relating to internal control and how to manage risk and internal control (Mallin, 2010). Following the Turnbull Review, the new Combined Code was set up in 2006 and introduced the following key principles: the roles of a company’s chairperson and chief executive; the composition of the company’s board of directors; and the composition of the board’s three main committees, namely the Nominations, Remuneration and Audit Committees (Pass, 2006). In 2009, the Turner Review was set up in response to recommendations regarding the changes in regulation and the supervisory approach based on the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s request in October 2008 for the assessment of the causes of the then- current crisis (Turner, 2009).

6. Corporate Governance Mechanisms and Their Role in Organizational Performance

- Corporate governance mechanisms are the procedures employed by companies to solve corporate governance problems; however, the use of these mechanisms depends on the corporate governance system (Weimer & Pape, 1999). Firms need internal mechanisms of corporate governance to mitigate the probability of having agency problems. These instruments and their role are as follows:

6.1. Role of Board Size

- The board of directors has been considered a vital corporate governance mechanism for aligning the interests between managers and all stakeholders in a firm (Sanda, Garba & Mikailu, 2011). Zahra and Pearce (1989) classified two main roles of the board: it should control the operations of the firm and the activities of the CEO; and it should enhance the image of the firm and sustain a good relationship between the stakeholders and firm management to encourage the organization culture. The Cadbury Committee (Cadbury, 1992) recommends an ideal board size of 8–10 members, with an equal number of executive and non-executive directors. Lipton and Lorsch (1992) argue that board size should be small and limited: a board size of 8–9 directors is optimal for coordination and communication, because if the board has more than 10 members, it is not easy for directors in the board to indicate their opinions and ideas. However, Dalton and Dalton (2005) argue that the advantage of larger boards is the spread of expert advice and opinions around the table compared to a small board. Larger boards are expected to increase board diversity in relation to experience, skills, gender and nationality.

6.2. Role of Leadership Structure

- The separation of the role of the CEO and the chairman is essential in alleviating issues of corporate governance practices in banks (Brickley, Coles & Jarrell, 1997; Dalton et al., 1998; Dedman & Lin, 2002). An important function of the board of directors is to monitor the performance of the top management (Varshney, Kaul & Vasal, 2012). This means that the combined leadership will have more managerial discretion because its leader is also the leader of the board of directors. Therefore, the board will have less incentive to monitor the activities of the corporate managerial team, which will increase information asymmetry between the agent and its principles (Zhang, Li & Zhang, 2011). Based on the agency theory, the CEO and chairman should be separate because the chairman cannot accomplish these functions without conflicts of personal interests (Jensen, 1993). Cadbury (1992) believes that the role of chairman should, in principle, be separate from that of the chief executive; if the two roles are combined, it represents a considerable concentration of power within the decision-making process.

6.3. Role of Board Composition

- An effective board director with an appropriate composition of directors is important to help the board accomplish its aim and ensure the success of the company (Al-Matari et al., 2012). The composition of the board has a direct effect on the company’s activities (Klein, 1998). Generally, the composition of the board refers to the proportion of inside and outside directors serving on the board. Boards of directors include both executive and non-executive directors.Executive directors refer to dependent directors, while non-executive directors refer to independent directors (Ali Shah, Butt & Hassan, 2009). The Cadbury Report (1992) indicates that the presence of non-executives should be effective in enhancing board independence and firm performance. The board of directors should consider an appropriate balance between executive and non-executive and independent board members, if at least one-third of members are independent members and that most members are non-executive members. Non-executive directors are outside directors who offer checks and balances to protect the interests of shareholders, and inside directors, who participate directly in the day-to- day management of the firm (O’Sullivan & Wong, 1998; Petrovic, 2008; Wan & Ong, 2005; Klien, 2002a). Fama and Jensen (1983b) argue that a higher proportion of independent non-executive directors increases board effectiveness in monitoring managerial opportunism and, consequently, increases voluntary disclosures.

6.4. Role of Board Committees

- Board committees are also an important mechanism of the board structure providing independent professional oversight of corporate activities to protect shareholder’s interests (Harrison 1987). The agency theory principle of separating the monitoring and execution function is established to monitor the execution functions of audit, remuneration and nomination (Roche 2005). The Cadbury Committee report in 1992, recommended that boards should nominate sub-committees to address the following three functions: - audit committees to oversee the accounting procedures and external audits;

- remuneration committees to decide the pay of corporate executives; and

- nominating committees to nominate directors and officers to the board;

These named committees can be just a window dressing unless they are independent, have access to information and professional advice, and contain members who are financially literate (Keong 2002). Therefore, the Cadbury committee and OECD principles recommended that these committees should be composed exclusively of independent non-executive directors to strengthen the internal control systems of firms (Davis 2002; Laing & Weir 1999).

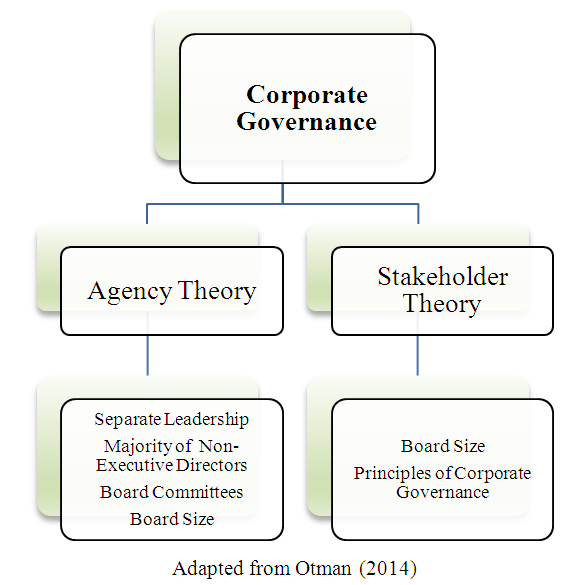

7. An Overview of Banking System in Cape Verde

- Cape Verdean financial sector has a sound and healthy banking sector. The banking system which holds more than 80% of the financial system’s assets in Cape Verde plays an important role in allocating resources to finance the Cape Verdean economy (BCV 2015). The commercial banks operating in Cape Verde are Banco Comercial do Atlántico (BCA), Caixa Economica do Cabo Verde (CECV), Banco Interatlantico, Banco Espirito Santo Cabo Verde, Banco Africano de Investimentos (BAI), Ecobank and Banco Caboverdiano de Negocios (BCN). The first six of these institutions are branches of foreign banks. Banco Caboverdiano de Negocios has majority local ownership and a Portuguese bank, which holds 46 percent of its share capital, has an option to purchase an additional 5 percent to give it majority ownership. Private sector ownership of financial institutions is a relatively recent phenomenon in Cape Verde. Up to 1993, the Bank of Cape Verde (BCV) was both the monetary authority and the sole commercial banking entity. In 1993, BCV ceased its commercial banking activities which were taken over by Banco Comercial do Atlantico.According to the 2016 annual report of Central Bank of Cape Verde, two dominant commercial banks account for around 90 percent of assets and deposits, which are Banco Comercial do Atlantico (BCA) and Caixa Economica de Cabo Verde (CECV).Credit is allocated on market terms and is available to foreign and domestic investors without discrimination. Credit to the private sector climbed to around 50% of GDP in 2010.The government remains active through financial institutions that handle public investment and international aid. The legal and institutional framework for the Cape Verde Stock Exchange has been strengthened.

|

8. Legal Framework for Corporate Governance in Banks in Cape Verde

- The constitution of the republic of Cape Verde, the organic law of the Central Bank of Cape Verde (“lei orgânica do Banco de Cabo Verde”), together with the code of commercial enterprises (“Código das empresas comerciais”) and the code of security exchange (“Código dos valores mobiliarios”) are the main regulatory framework for corporate governance in banks in Cape Verde. Authorities are actively pursuing reforms to regulatory and supervisory frameworks and revising banking laws in efforts to further safeguard financial stability. Planned measures include establishing of macro-prudential unit within the central bank, enhancing supervisory procedures and strengthening supervisory capacities, and developing prudential regulations to address credit, foreign exchange and interest rate risks. The implementation of the code of corporate governance practices and the institute for corporate governance of Cape Verde are also measures that Cape Verdean authorities are taking.

9. Conclusions

- Corporate governance has become an essential problem in both developing and developed countries (Kelton and Yang, 2008). From the review, we can say that corporate governance is linked with the management relationship and between other stakeholders and board of directors. This emphasizes the need for a holistic review and understanding of the concept. The factors of corporate governance could be examined in Cape Verdean banks in the form of existence of independent department of risk management, non-executive directors, audit committee and proportion on board, board composition, board nomination. Future researches might test empirically how financial performance banks in Cape Verde are impacted by corporate governance mechanisms. To achieve higher standard of corporate governance and to prevent difficulties that banks can come through, for instance, high level of non-performing loans and some other problems, Cape Verde should introduce the code of Corporate Governance practices and create the institute for corporate governance.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML