-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2017; 7(3): 103-109

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20170703.01

Financial Domain as a Tool in Measuring Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) Performance in Kenya

Nasline Akinyi Ouko1, Raphael Nyonje1, David Omondi Okeyo2

1Departmentof Extra Mural Studies, The University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

2Kenya Nutritionists and Dieticians Institute, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Nasline Akinyi Ouko, Departmentof Extra Mural Studies, The University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Performance measurement among NGO’s takes critical perspective within the Balanced Score Card (BSC) domain. The BSC emphasizes four dimensions which include customers’ perspectives, financial perspective, internal, business and organization learning dimension. Financial perspectives received least consideration among NGO’s due to their non-profit nature. However, this aspect needs to be given equal priority just like other components. This article attempts to demonstrate the focus given on financial components among NGO’s with livelihood orientation and operating within western Kenya. The study administered 64 questionnaires to all top management of NGO’s. The results revealed four components of financial domains in performance measurement. Accounting processes, audit processes, procurement and asset building, and budget flexibility and adjustment emerged as key issues of finance in performance evaluation base on variance accountability generated by principal axis factor analysis. The study concludes that financial perspective of performance measurement within NGOs would prioritize accounting, audit, procurement and asset building and budget flexibility and adjustment in that order. It recommends that NGO’s and stakeholder need to consider social returns on investment as a quantitative profit equivalent measure of performance.

Keywords: Performance, NGO, Financial perspective, Accountability

Cite this paper: Nasline Akinyi Ouko, Raphael Nyonje, David Omondi Okeyo, Financial Domain as a Tool in Measuring Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) Performance in Kenya, Management, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 103-109. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20170703.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Financial perspective as domain and a measure of performance in the Non-governmental organization (NGO) includes the measurement of operating income, return on capital and economic value added (Hartnett and Matan, 2011). NGOs just like profit companies, must have a solid understanding of their financial situation. Timely data on funding sources; cost of services and overhead costs must be incorporated into the non-profit’s strategic plan to provide a complete picture of the situation. The leadership must be comfortable with the financial statements and budgets which provide solid basis for operations and build confidence with funding, grantors and other sources of revenue.This perspective can also be looked at in the context of financial strategic objectives and financial performance measures that provide evidence of whether or not the company’s financial strategy is yielding increased profitability and decreased costs. This view also captures how the organization must look to the customers in order to succeed and achieve the organization’s mission (Ronchetti, 2006). Niven (2008) asserts that the financial perspective of the Balanced Score Card is imperative for non-profits because it captures information about how efficiently they are using scarce resources and public/donor funds to offer quality services. This perspective improves organizations accountability towards the public and enhances its fund raising potential, consequently, making mission achievement much imminent. Niven (2003) further argue that no organization, regardless of its status, can successfully operate and meet customer requirements without financial resources. Financial measures in the public and non-profit sector scorecard model can best be seen as either enabler of customer success or constraints within which the group must operate. According to Niven (2002) an organization which is using significant time and resources on improving internal processes may effectively add little value if these improvements are not translated into improved financial performance.Financial performance of NGOs can also be defined in terms of financial accountability. Financial performance has been one of the key elements in measuring overall performance and evaluating effectiveness of non-profits (Speckbacher, 2003; Ritchie and Kolodinsky, 2003; Sowa, Selden and Sandfort, 2004; Mc Cathy, 2007). As far as donors and community stakeholders are concerned, financial accountability focuses primarily on a non-profits reputation for fiscal transparency and honesty (Keating and Frumkin, 2003). More often than not accountability is represented by the data on these the use of external independent auditors, operating standards, audit committees and boards’ expertise (Whitaker et al 2004; Greenlee, et al, 2008). A part from fiscal transparency, financial efficiency relates to the amount of money needed to bring in revenues and access funding sources. Ritchie and Kolodinsky (2003) identified three categories of financial performance that foundations use to evaluate the financial efficiency of non-profits: fundraising efficiency, fiscal performance and public support. The last approach to assessing financial accountability is performance based budgeting (Joyce, 1997) in which funding and spending are linked to the actual goals strategies, programmes, revenues, services and results (Moravitz, 2008). Performance based budgeting consist of the following critical elements: creation of strategic plans linking missions with programmes, link strategic objectives to goals through a performance plan, use the budget to support the performance plan and priorities based on the financial resources and assessing progress against the plan periodically. Melkers (2003) argues that this approach encourages non-profits to move away from traditional line item budgets to those that are truly linked to service outcomes that document their social impact. Although NGOs are not financial generating entities, they are accountable to the funds donated by the benefactors. Therefore, a clear measurement and indication of how financial resources are managed become critical and necessary elements for NGOs’ performance evaluation (Bin Md. Som and Theng Nam, 2009). The frameworks and systems commonly used to assess the success of donor-funded development projects are based on an underlying assumption that NGOs should be accountable to their key stakeholders, most importantly to their donors and beneficiaries (Cutt and Murray, 2000). But accountability is not just about donor control. It includes the fulfillment of public expectations and organizational goals as well as responsiveness to the concerns of their wider constituency. It is also noted by Abraham (2006) that NGOs with high asset turnover are considered as generating more programmes or services than those with low asset turnover. Moreover, NGOs with low turnover are more likely to invest their assets to earn income than to provide services. The liquidity ratio measures the relationship between assets and liabilities and also helps to determine the consistency of goals and resources. This study attempted to demonstrate the focus given on financial components among NGO’s with a focus on livelihood NGOs operating within western Kenya. Major research question dwelt on what components of financial perspectives drawn from balanced score card apply in financial management of livelihood oriented NGO’s in Western Kenya.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Group, Data Collection and Piloting

- The study population was drawn from NGOs operating in Kisumu County. This county is located in Nyanza and borders Lake Victoria to the West, Siaya, Vihiga and Nandi counties to the North, Kericho County to the East and Homa Bay County to the South. The region covers an area of 2,086 Km2 and has a population of 968,909 individuals. A cross-sectional analysis was conducted among 64 managers drawn from a sampling frame of 76 top 3 top managers including programme/project managers, monitoring and evaluation, and accountant of Non-Governmental Organizations. This sampling frame only constituted a census of all the active NGO’s with livelihood orientation operating in Western Kenya. Semi-structured questionnaire thematically organized was used to capture the key elements in financial perspectives theoretically drawn from the Balanced Score Card concept. The financial perspective had a set of item measures with a focus on expenditure as budgeted, expenditure within the variance, expenditure on need arises basis, flexibility on budget adjustment, control over purchases, control over cheque payment, control over bank account, control over payroll, control over fixed assets, regular financial statements and financial reports for managers.The instrument for data collection was first subjected to validity and reliability tests. Construct validity was assessed by evaluating the opinion of the respondent against each score using principle axis factoring. The researcher used simple, clear and non-ambiguous language in the instruments. All the questionnaires were verified to check if all the questions were well answered to the end to ensure validity of collected data. The research instrument was administered to the 15% of the respondents and data obtained split into two sub sets (the sets had odd numbers and even numbers). All even numbered items and odd numbered responses in the pilot study were computed separately. Reliability test statistics based on Cronbach alpha revealed coefficients greater than 0.7 across all perspective measures. This indicated an acceptable instrument. The 64 questionnaires were then randomly administered by the researcher to the respective managers in their offices upon booking of appointments.

2.2. Data Analysis Techniques

- Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics where quantitative and qualitative approaches were used. Quantitative data analysis was done by objectives. Data collected using semi-structured questionnaires was entered into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19.0 spreadsheet and cleaned. Descriptive statistics were run to establish the accuracy of entry of scores by assessing range, mean, standard deviation and normality of data. Inferential statistics mainly hierarchical regression was used to assess the contribution of each of the perspectives as performance measurement measures by objectives. In this analysis all the item measures for each perspective were subjected to descriptive analysis followed by factor analysis and finally linear regression to show the most widely practiced aspects of the key measures of perspectives. All the data were analyzed at 95% level of significance and the degrees of freedom.

2.3. Ethical Consideration

- The researcher obtained a research permit from the National Council of Science and Technology headquarters allowing her to collect data from Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in Kisumu County. Before the study was conducted, the proposal was presented to the University of Nairobi for approval. Relevant local authorities were informed of the study for clearance to access the Non-Governmental Organizations. Verbal consent was sought from the respondents before they participated in the study. The respondents who chose to participate were assured that the information they gave was confidential and would not be used for any other purpose except for this study. Every questionnaire remained anonymous, as the respondents were only assigned identity numbers instead of writing their names.

3. Results

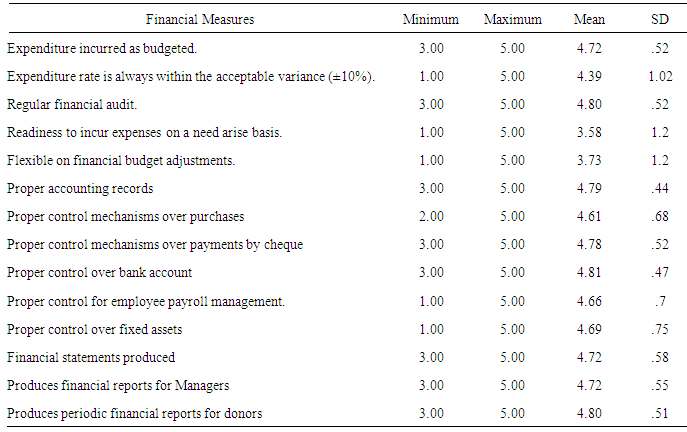

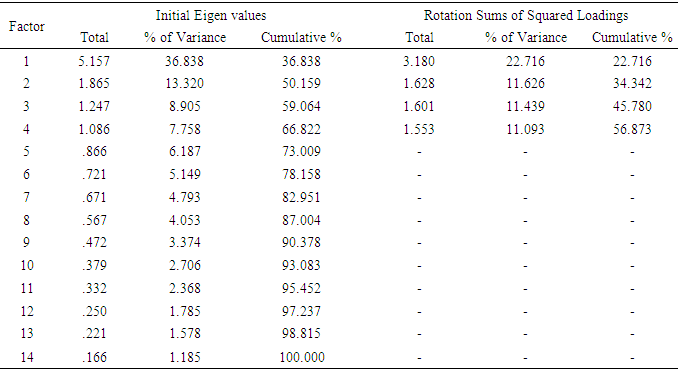

- The financial performance of Non-Governmental Organizations is defined in terms of financial accountability. Financial performance has been one of the key elements in measuring overall performance and evaluating effectiveness of Non-Governmental Organizations. The study sought to demonstrate the focus given on financial components among NGO’s with a focus on livelihood NGOs operating within western Kenya. In this study, the financial perspective had 14 item measures put to test for their applicability in the Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO). Descriptive statistics were run for all the items to assess for the accuracy of entry of data and mean score for each item and were summarized in table 1.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

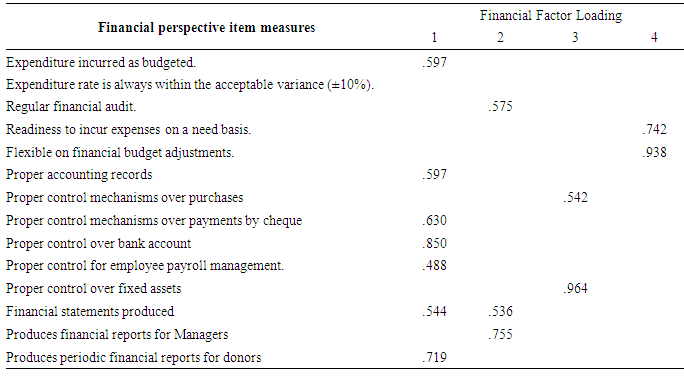

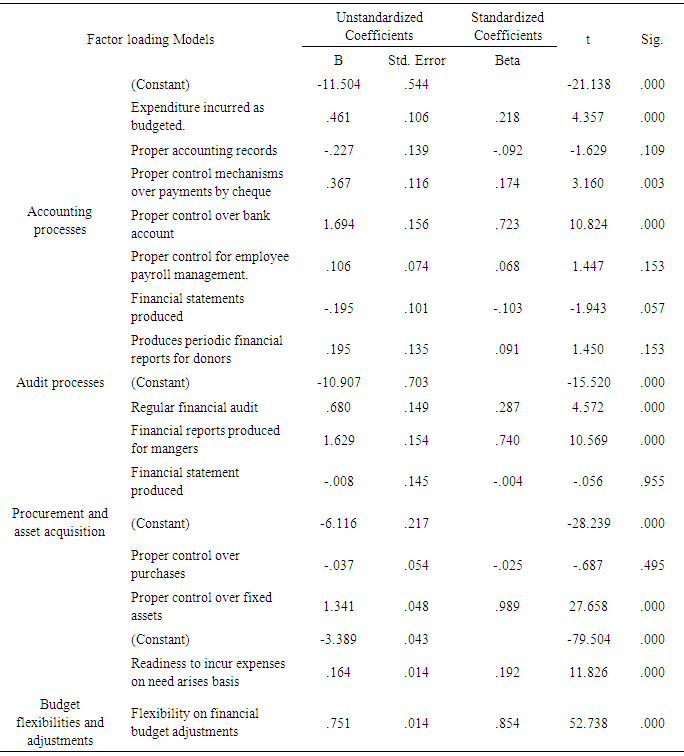

- These study findings based on managers’ perceived opinion identified four financial related perspectives in the NGO management. The first category loaded 7 item-measures which depicted a theme tailored towards “accounting processes” mechanisms. The second category of financial domain characterized by three items thematically resented “audit processes” mechanisms. These two themes seem to suggest that many NGOs value internal controls as part of performance area. The third prioritized financial aspects seemed to zero in “procurement and asset acquisition” mechanisms. The forth dwelt on “budget flexibilities and adjustments”.

|

5. Conclusions

- The study concludes that financial perspective of performance measurement within NGOs would prioritize accounting processes, audit processes, procurement processes and asset processes and building budget flexibility and adjustment in that order.

6. Limitations of the Study

- This study was limited to NGOs top management’s opinion and may not be generalized for all employees within the NGO sector. More so the scope covered livelihood oriented NGOs and could be useful within this citation. However, the knowledge generalized represents typical organizations management and behaviour and somehow it reflects a true situation of NGOs performance evaluation within the BSC framework. Further, it appears that there are limited literatures focusing on the financial perspective of performance evaluation among NGOs. This could be attributed to the non-profit nature of such organizations which limits focus on financial accountability.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML