-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2016; 6(5): 158-184

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20160605.03

The Threads of Organizational Theory: A Phenomenological Analysis

Sunday Tunde Akindele 1, Yakibi Ayodele Afolabi 2, Oluyemisi Olubunmi Pitan 3, Taofeek Oluwayomi Gidado 4

1Department of Political Science, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

2Department of Business Administration and Management, Osun 5 State Polytechnic, Iree, Nigeria

3Department of Counselling, School of Education, National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos, Nigeria

4Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Sunday Tunde Akindele , Department of Political Science, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper examines the theory of organization in the context of its evolution of organizations over the years. It choreographs the intellectual attentions on the subject matter of organizational theory and its accompanying paradigmatic influences within the period. In the process the pedigree of organizational theory and its relevance to the anatomy of real organization up to this millennium was traced. This enabled a proper discussion and analysis of situation of the classical works of the theorists of who have contributed in no small measure to the expansion of the frontiers of our knowledge in the area. The concept of organization was examined as a prelude to the genealogical discourse and consideration of the threads of organizational theory within the context of the relevant paradigm changes. Against this background, the evolution of the subject, using appropriate models, was thoroughly examined in ways that puts into a clearer context the currency of ideas on the phenomenon of organization and its theory or theories.

Keywords: Organizational Theory, Organization, Bureaucracy, Human Relations, Leadership, Delegation, Management by Objective

Cite this paper: Sunday Tunde Akindele , Yakibi Ayodele Afolabi , Oluyemisi Olubunmi Pitan , Taofeek Oluwayomi Gidado , The Threads of Organizational Theory: A Phenomenological Analysis, Management, Vol. 6 No. 5, 2016, pp. 158-184. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20160605.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- People at all levels of social experience pursue their materials and spiritual goals within the structure of organizations as “miniature societies in which the dominant values of society are inculcated and sought in a more structured, spatially restricted context” [1], [2]. Thus, nearly all activities of the individuals fall within the parameters of organizational norms and values. This explains the position that “man is intent on drawing himself into a web of collectivized patterns. Modern man has learned to accommodate himself to a world increasingly organized [3]. Typically, individual tends to define himself or herself and, his or her position relative to society by referring to organizational membership. And, the pervasiveness of this condition or tendency has permeated the nerves of every society thus lending credence to the ubiquity and importance of organizations and, the constant tendencies for theoretical constructs on the concept by various theorists at different points in time within the society. The essence of this can be located within the parameters of the fact that nearly everybody in the society belongs to one or more organizations. And, there is usually overlapping of organizational membership. Assuming this is correct, one needs to ask the question: what is an organization?Taking the foregoing into consideration, one may be tempted to assume that the definition of the term organization is a simple one, but this is not so. The concept of organization is not free from definitional pluralism and its accompanying intellectual disputations which constitute a common rule of the thumb within the discipline of political science and other social sciences.Various definitions of organization have been given from different perspectives a trend which conveys the complexity of the subject matter of this paper. Chester Barnard [4] defines organization as a “system of consciously coordinated personal activities or forces of two or more persons”, while Victor Thompson [5] cited in Waldo [6], [7] takes organization as “a highly rationalized and impersonal integration of a large number of specialists operating to achieve some announced specific objectives” through a “modern bureaucracy” predicated on “specialization” and, “an hierarchical framework” [5]. This, on its own was articulated by Robert Presthus [2], as “structural characteristics of specialization, hierarchy, oligarchy and interpersonal relations that are explicitly differentiated by authority”. Thus, organization is “a continuing system of differentiated and coordinated human activities utilizing, transforming and welding together a specific set of human, material, capital, ideational and natural resources into a unique, problem-solving whole whose function is to satisfy particular human needs in interaction with other systems of human activities and resources in its particular environment [8], [6], [7].In contributing to the analytical appraisal of the concept of organization, Talcott Parson [9], likened organization to “a broad type of collectivity which has assumed a particularly important place in modern industrial societies –the type of which the term “Bureaucracy” is most often applied”. He conceptualized organization as “the special type of social system organized about the primacy of interest in the attainment of a particular type of system goal”. He went further to contend that “an organization is conceived as having a describable structure” which can be analyzed from two broad perspectives both of which are “essential to completeness” and; explicated the two perspectives as inclusive of both “cultural-institutional” and “group” or “role” points of view . Consequent upon this he articulated his position thus:An organization is a system which, as the attainment of its goal, “produces” an identifiable something, which can be utilized in some way by another system; that is the output of the organization is, for some other system, an input. In the case of an organization with economic primacy, this output may be a class of goods or services which are either consumable or serve as instruments for a further phase of the production process by other organizations. In the case of a government agency the output may be a class of regulatory decisions; in that of an educational organization it may be certain type of “trained capacity” on the part of the students who have been subjected to its influence. In any of these cases there must be a set of consequences of the processes which go on within the organizations, which make a difference to the functioning of some other sub-system of the society; that is, without the production of certain goods the consuming unit must behave differently i.e., suffer a “deprivation” [9].These various definitions notwithstanding, it can be argued to a significant extent that nearly all organizations have specialized and limited goals and, that they are “purposeful complex human collectivities, characterized by secondary (or impersonal) relationships, integrated within a larger social system, providers of services and products to their environment, dependent on exchanges with their environment, sustained co-operative activity” [10]. The pervasiveness of organization in human society is undeniably a progeny of the metamorphoses of human society per se. Hence, as once noted “some of the reasons for intense organizational activities are found in the fundamental transitions which revolutionized our society; changing it from a rural culture to a culture based on technology, industry and the city. And, that from these changes, a way of life emerged characterized by the proximity and dependency of people on each other” [3]. It has been further argued that “traditionally, organization is viewed as a vehicle for accomplishing goals and objectives” even though, its conceptualization so far tends to erect a veil on the inner dynamics (i.e., both the inner workings and internal purposes) of the organization itself.Organization has equally been conceived as a purposeful mechanism for offsetting or neutralizing forces which are capable of undermining human collaborative existence. Thus, organization acts as a “minimizer” of conflicts through the lessening of individual’s behavior which is usually subjugated to the dictate of the organization’s orientation. In the process, it has been articulated that “organization enhances the predictability of human action because it limits the number of behavioral alternatives available to an individual” [3]. This standpoint, has equally once been emphasized by Robert Presthus in his definition of organization as “a system of structured interpersonal relations (within which) individuals are differentiated in terms of authority, status and role with the result that personal interaction is prescribed or structured (through which) anticipated reactions tend to occur, while ambiguity and spontaneity are decreased” [11], [12], [1], [2].The ubiquity of these factors and, the pervasiveness of individual’s membership in one or more organizations as already articulated, has led to the genesis within the disciplinary parameters of the social sciences a sub-field called “the organizational theory” which deals with the revelation of organizational behavior, membership or, the chemistry of organizational structure. Organizational theory is a progeny of various inspirations ranging from the drive to improve industrial organization’s productivity to the observation of human behaviors or, the introduction of rationality and predictability into (social) organizational relations. Variables like internal structure, authority relationship, roles and other features have long formed the kernel of the concerns of organizational theorists. Organizational theory in the real sense of the concept has been argued to have begun with the pioneering work of the German classical sociological writer and thinker, Max Weber (1864-1920). It was Weber who brought to our attention the characteristics of organizations as exemplified by the now universally acclaimed concept of bureaucracy and its features of hierarchy, rules, authority, procedures, officialdom, expertise, impersonality, division of labor among others [10], [6], [7]. However, given the eclecticism of the social and management sciences, it should be stated at this point that, we are not unmindful of the scholastic contestation of the claim of preeminence on the genesis of organizational theory. This is particularly so in the sense that there seems to be a contradiction regarding the actual school of thought that formed the foundation of organizational theory. While it has been argued by some that, human relations school preceded the classical school, others have argued differently or, to the contrary. While some theorists belong to the school that gives preeminence to human relations school, others belong to the latter which confers preeminence on the classical school of thought [10], [13], [14], [15]. In fact, Shafritz and Whitbeck [15], rated Max Weber [16]-whose work on “Bureaucracy” of 1922 was later republished in 1946 [17] - fourth on the preeminence scale after Adam Smith, Frederick Taylor and, Henri Fayol [18], [19], [20], [21]. In his own contributions to the issue of preeminence of scholars in their contributions to the subject matter of organizational theory and its evolution or growth, Scott [3] argued that organizational theory has gone through many stages –“classical theory”, “neo-classical theory”, to “modern organizational theory.” According to him “classical theory of organization is concerned with principles common to all organizations”. It is a macro-organizational view that deals with the gross anatomical parts and processes of the formal organization. He summed his view of the development or metamorphoses of the organizational theory and the reasons for it thus “many variations in the classical administrative model result from human behavior. The only way these variations could be understood was by a microscopic examination of particularized situational aspects of human behavior. The mission of the neo-classical school is thus “micro-analysis…and, the forcing of the social system into limbo by the neo-classical theorist led to the emergence or genesis of modern organization theory” [3]. The features or principles associated with the theory in all stages of its development or transition as articulated by the various scholars on it subject at the various stages could be said to have now become the nerves of modern organizational structures in today’s world. Thus, organizational theory is now an area of inquiry shared by various disciplines like sociology, psychology within the social sciences. And, like other concepts of “public policy”, “public choice theory”, “structural functionalism”, organizational theory has gained penetration into the realm of political science as a sub-field.As a sub-field within the discipline of political science, the concept of organizational theory has not been free from problems. One of the problems has to do with the multiplicity of its definitions which, as Peter Self [22] once articulated, tends to suggest the liability of organizational theory to fall into the fallacy of “misplaced concreteness”. Thus, according to Self [22] one need to ask whether “organizations are properly regarded as separate entities having lives, histories of their own, and subject to ascertainable laws of growth and decay” or, “they consist rather of fluctuating and overlapping systems of co-operative action possessing only a small degree of autonomous behaviour and intelligible mainly in terms of wider systems of social behaviour”. The need for this clarification and avoidance of the fallacy of “misplace concreteness” on the subject matter of organizational theory according to Peter Self is compelled by the fact that:While both concepts may be valid within limits, the choice of the first approach easily leads into dubious beliefs about the solidity and autonomy of particular organizations. This may be reflected in a tendency to believe that all the intellectual descriptions that can be offered of the functioning of an organization are practically significant or meaningful. It is generally agreed that an organization does not consist of a set of persons and equipment, but of a system of co-operative action governed by rules and by actual or presumed objectives. An individual often belongs to many organizations. Not only do organizations extensively overlap in membership but they also often form cumulative pyramidal systems or linked horizontal systems. The most usual definition of formal organization is a juristic one, expressive of legal status, rights and liabilities. However, a legally defined organization is sometimes a relatively weak centre of decision-making and may be controlled to a large extent from other centres. The definition and enumeration of organizations poses considerable problems [22]. Against this analytical premise, Self [22] further contended that:Organisation theory is prone to the fallacy of ‘misplaced concreteness’ when it supposes that organizations possess clearer boundaries, greater autonomy and stronger loyalties than they do. The theory that the first aim of an organization is survival is in a sense a tautology. A particular organization cannot continue with its work if it ceases to exist. The theory that the second organizational aim is growth is not a tautology, and is often, but not universally, true. Growth frequently enables an organization to pursue its goals more effectively, to enjoy greater stability in relations with its environment, and to offer greater satisfactions to its members. Thus it is natural to hypothesize that most organizations possess intrinsic tendencies towards growth, if circumstances permit. However, every organization is composed of individuals, each of whom has his or her personal aims which will frequently be different from those pursued by the organization as a whole. The willing support of most members is contingent upon some agreement between personal and organizational aims, and their support is also related to the possibilities of pursuing personal aims more effectively by switching to some other organization; this is so whether personal aims are material or ideal, selfish or altruistic.Another problem is that organizational theory does not actually provide much help with the evolution and resolution of administrative conflict. It is dormant along this dimension and, also silent with regards to the question of how much and, what kind of competition is desirable between parts of the administrative system and how such competition should be structured [22]. As a matter of fact, the combination of these problems and, the need to gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter of this concept has long constituted weighty challenges to political scientists within the discipline of political science and its sub-discipline of public administration and other related fields most of which seemed to have assumed independent disciplinary status or, are claiming to be independent or distinct from political science within the disciplinary parameters of the social sciences. Thus, these challenges continue to dominate scholarship and the pursuit of the expansion of the frontiers of our knowledge within these disciplines and fields up to this period and, the trend shows no sign of dissipation as far as the future of the disciplines and others is concerned.Given this preamble, this paper is a theoretical expedition into the genesis of organizational theory. It attempts to explore its development up to the current era of globalization tracing the various characteristics of the paradigms that have dotted its growth and development from the classical period. It intends to highlight and elucidate the various contributions of scholars, researchers and practitioners on its subject matter over the years. It equally intends to examine the issue of the classicalism of the organization theory itself and its implications and challenges for today’s administrators and, the administrative landscape in which they may find themselves. In the pursuit of the goal in the paper we have divided it into four broad sections some of which have sub-components. The introduction provides the choreography of the paper as well as the definitional explication of the concept of organization as applicable within the context of our focus. Section one treats the subject matter of organizational theory while section two examines its growth from the classical era to the neo-classical era. The core of the analyses in this section, deals with the contributions of the various scholars, researchers and practitioners as they affect the different paradigms the theory has passed through. While section three deals with the critiques of the doctrines from the classical; neo-classical to the newer traditions section four contains a detailed analysis of the foundational articulations of the organizational theorists on the subject matter of the paper. The conclusion provides relevant prescriptions for today’s administrative landscape and scholarship. It raises a poser as to what lies ahead concerning the theory of organization within the context of the planetary phenomenon of globalization and its thesis which has been predicated on the catechism of a “global village” [23].

2. The Subject-Matter of Organizational Theory

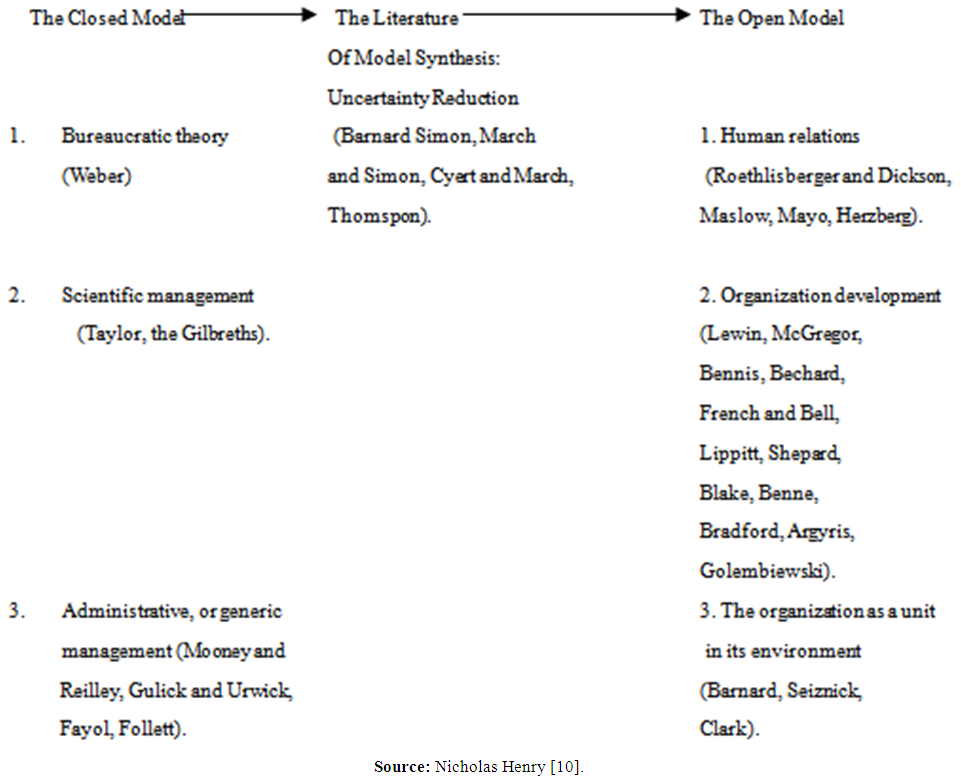

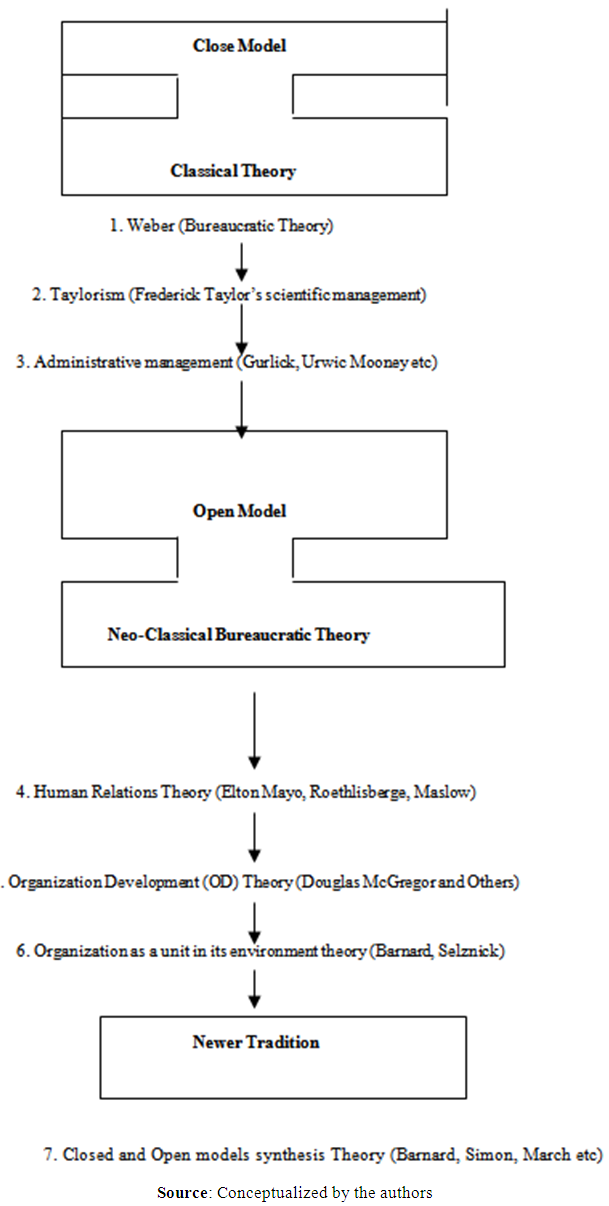

- The concept of theory even though, debatable, is indispensably relevant to all human phenomena. This continues to be significantly so in today’s world amidst the demands of the current planetary phenomenon of globalization and its attendant “villagization” of the world into a single community through a “transcendental homogenization of political and socio-economic theory across the globe” [23]. And, in spite of the entrapment of the global village or community by these new developments and the octopus of globalization and its assumed homogenized socio-economic and political values predicated on its uneven thesis, it still faces the challenges of the multidimensionality of human needs and aspirations within organizations and human settings which on their own continue to provoke the need for theoretical constructs concerning the plights, existential conditions, needs and situations of those in such organizations. Thus, theory as a concept, has come to occupy a central place in the systemic existence of the universe and all entities within it including all humans and all the issues that have to do with their survival and continuous search for orderliness and fulfillments to mention only a few.This has been largely so in that, regardless of the geo-political location within the globe the structural orderliness, meaning, development, co-ordination, purposeful planning, futuristic predictions and predictability in our society are any without doubt predicated on the foundation provided by theoretical constructs. And, one of such theoretical constructs that has gained pedagogical, scholastic and humanistic prominence within the organizational world over the years is organizational theory.Given these realities this paper considers the subject matter of organizational theory as a prelude to the analysis of its developmental trend exemplified by the works of various scholars and paradigmatic changes that have characterized its growth. This discourse itself is premised on the theoretical arguments and analyses of some scholars on the subject matter. These works are genealogically discussed; reviewed and; analyzed in this paper to bring them into contemporary reach of people within the academia and the world in general at this period of globalization and its supersonic transformation in information technology.The discourse is motivated by the need to highlight some of the issues that have evolved over the subject matter of organizational theory and its development over the years. Not only this, analysis of any phenomenon can only be meaningfully carried out on the basis of its conceptual understanding through appropriate definition(s). Generally, the development of organizational theory as a “science” or, towards a “science” since the 1930s has been subjected to various criticisms which need attention the kind of which can be given through the conceptual analysis we envisage in this paper. Dwight Waldo’s [6], [7] articulation below lends credence to our contention in this regard:A definition of organization is a theory of organization-at least a crude sketch of a theory-for it must necessarily try to state in general, more or less in abstract terms what the essentials are and how they relate…..It seems outrageous (or indifferent to matters of importance) to try to proceed to a careful examination of any phenomenon (e.g., organization) without an attempt to define, that is, to understand and agree upon what the object of examination is, at least in general terms and as now understood.Thus, contemporary organizational theory which has been called “behavioral”-(due to its focus on the individuals’ - personality- within the organizational set up), - according to Dwight Waldo “represents an inter disciplinary approach and, views organizations as social milieu in which the individual is concerned with factors like his role, status, perception of authority and leadership as well as the role of the organizations in society”. This explains his definition of organizational theory as “a conceptual scheme, the aim (but not necessarily the achievement) of which is to enable us to understand, to predict, and to control (if we wish) organizational phenomena” [6], [7]. Within the confines of studies dealing with organizational theory, it has been emphasized that “modern man’s life is the product of living in a society in which most of his life is organized for him”. This suggests that organizational theory is not concerned with personality but with those aspects of behaviors which are determined by organizational structures. And, that “organizational theory provides the grounds for management activities in a number of significant areas of business endeavor and, that, it is not a homogenous science based on generally accepted principles” [3].In his further analysis of the concept of organizational theory, Waldo [6], [7] treats it as a corollary of administrative theory though, of a less value-involvement than the latter. The scholar tied the genesis and rise of organizational theory to various sources including the birth of behavioral orientation and, the often cited notion that ours is an age of organization. He summed his position on this aspect thus:In general, among those concerned with the scientific approach to the study of “co-operative actions”, there has been something of a movement away from the terms (like) “administration”, “administrative”, and “administrative theory” to the terms (like) “organization”, “organizational”, and “organizational theory”.According to this scholar, mood of behavioralism were responsible for this movement in the behavioralists’ quest for scientific method in their study of social phenomena. Thus, as Scott [3] noted, various theories of organization have been and, are being evolved as exemplified by the emergence of modern organization theory which, while incurring the wrath of the traditionalists have captured the imagination of a rather elite avant-garde within the scholarship of political science and public administration and, the administrative landscape.This movement and the metamorphoses it has brought to the concept of organizational theory within the disciplines of political science and public administration have been variously characterized and elucidated by scholars, researchers and practitioners within the theoretical and practical world of public administration. This movement which dates back to the classical epoch refers to “the beginning of the beginnings” from our perspective. The metamorphoses inherent in this movement have been variously tagged or conceptualized by various writers. According to Scott [3] the metamorphoses could be tagged “classical”, “neo-classical”, and “modern” theories of organization. And, Waldo [6], [7], argues that organizational theory has spanned across various stages starting with the “classical stage” followed by the “neo-classical stage” and, ending up the “planners” (planning stage). Others have tagged them as transition from “closed-model” to “open-model” and, a possible synthesis of the two through the newer tradition. In fact, Henry [10] chronicles the evolution of organizational theory over the years right from the “classical conceptualization of organization” itself and, the views of man within the organizational setting (e.g. Weber’s bureaucratic theory, Taylor’s scientific management and, administrative management) to the “neo-bureaucratic theory” of organization which maintains a less pessimistic view and more liberalized notion regarding the positions of employees within the organization (e.g. human relations school, organization development, organization as a unit of analysis) and; the newer tradition (i.e., synthesis of “close and open models”). In short, this scholar trisected the evolution of organizational theory into major streams of “close” and “open” models and, “newer tradition” (synthesis) model.In contributing to the subject matter of organizational theory, this scholar utilized the definition of a model-(a tentative definition that fits the data available about a particular object) - as a prelude to the analysis of the actual threads or evolution of organization theory. The rationale for doing this as the scholar argued, is that “unlike a definition, a model does not represent an attempt to express the basic irreducible nature of the object and, it is a freer approach that can be adapted to situations as needed” [10]. He emphasized the fact that the use of model is appropriate in the commencement of the explication of organization theory due to the equivocal nature of the word organization. He premised his stand on this on the physicists’ position vis-à-vis the use of models in the explanation of phenomena thus:Unlike a definition, a model does not represent an attempt to express the basic, irreducible nature of the object, and is a freer approach that can be adapted to situations as needed. Thus, physicists treat electrons in one theoretical situation as infinitesimal particles and in another as invisible waves. The theoretical model of electrons permit both treatments, chiefly because no one knows exactly what an electron is- (i.e., no one knows its definition) - so it is with organization [10].This, in itself shows that the term organization means different things to different people. Thus, its meaning and evolution over the years have been articulated from various perspectives and contexts relevant or peculiar to the definer(s). However, it should be stated that, none of these changes or metamorphoses which cut across various periods or intellectual paradigms, can be explained, in isolation from the other. This explains the focus of sections three, four and five of this paper which while fully capturing the various paradigm changes, respectively deals with the evolution of organizational theory from its - (classical) - beginning to the present focusing on the general analysis of the movement or development on the subject matter of organizational theory itself; the criticisms of the threads of organization theory up to the neo-classical period leading to the newer tradition and; the respective organizational theorists and their positions as originally articulated by them in a way that more or less suggests a synoptic recapitulation of the articulated position in this paper. Even though, it may be difficult to differentiate the core of the analyses in these three sections, we have nevertheless attempted to make an effort in the direction we have chosen because of the eclecticism and challenging nature of the subject matter of our focus. This, in itself, dictates the nature of our conclusion.

3. Organizational Theory: From Classical to Neo-Classical

3.1. The Classical Doctrine

- Organizational theory has its origin embedded in the classical doctrine which deals primarily with the structure or anatomy of formal organization. This gave birth to what is today referred to as classical organizational theory. Classical organizational theory was the foremost theory of organization from which other or subsequent theories took their roots. According to Shafritz and Whitbeck [15] “classical organization theory as its name implies was the first theory of its kind. It is considered traditional and will continue to be the base upon which subsequent theories are based”. It is classical in the sense that it has been supplanted by other modern theories. Commenting on this Shafritz and Whitbeck [15] averred that “the honor of being acclaimed classical is not bestowed on anything until it has been supplanted”. This notwithstanding, its tenets continue to permeate the physiological fibers of modern day organizations.The pedigree of organization theory can actually be trace to the classical work of Adam Smith. This classical economist undoubtedly represented one of the parenting theorists of organization theory as it is known and regarded today. This has been summed up thus:It is customary to trace the lineage of present day theories to Adam Smith, the Scottish Economist who provided the intellectual foundation for laissez faire capitalism. His most famous work, an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations (1776), devotes its first chapter “of division of labor” to a discussion of the optimum organization of a pin factory [15].This puts to rest the issue of preeminence among the various scholars who have worked or contributed to the subject matter of organizational theory earlier highlighted based on the works of some management sciences’ scholars [10].The principles of scientific management euphemistically referred to as “taylorism” gained a wider currency about a century after Adam Smith’s concept of division of labor within the organization Frederick Winslow Taylor, the acknowledged father of the scientific management movement developed the time and motion studies. He based this study on “the notion of one best way” of accomplishing any given task. Taylorism sought to increase output by discovering the fastest, most efficient and least fatiguing production method [10]. And, once this best way was found, its imposition upon the organization was always the next step. The rationale for this imposition which could be interpreted as the organization’s desire to plug any possible avenue through which employees can cheat on the organization or go slow on the job thereby injuring the profit maximizing efforts of the organization is best put into perspective by the tayloristic perception of man within the organizational set up to the effect that “nineteen out of twenty workmen throughout the civilized world firmly believe that it is for their best interest to go slow instead of to go fast. They firmly believe that it is for their best interest to give as little work in return for the money they get as is practical”.In his own contribution to the historical evolution of the organizational theory, Scott [3] identified the formative stage of “taylorism” as part of the foundation of classical organizational theory. This is implicit in his argument that “the classical doctrine (or theory of organization) can be traced back to Frederick Taylor’s interest in functional foremanship and planning staffs”. This explains Dwight Waldo’s [6], [7] argumentative premise that:Scientific management is a theory that, taking efficiency as the objective, views administration as a technical problem concerned basically with the division of labor and the specialization of function…….It is the theory which distinguishes four organizational bases: purpose, process, clientele or material, and place; and designates the work of the executive as concerned with POSDCORB—planning, organizing, staffing, directing coordinating, reporting and budgeting. Its symbol is organization chart [6], [7].Lending credence to Waldo’s position, Scott [3] emphasized that “classical organization is built around four key pillars of division of labor, the scalar and functional processes, structure and, span of control”. Out of these, division of labor undoubtedly constitutes the cornerstone of the classical theory. Apart from forming part of the parentage of the classical conception of organization theory through the eighteenth century (1776) works of Adam Smith, division of labor occupies a central place in Max Weber’s explication of bureaucracy which is equally one of the various fibers that form the physiology of classical organization theory [15]. This tally with Waldo’s [6], [7] explication of Weberian bureaucratic model as part of the classical tradition in organizational theory and that, it gave primacy to the issue of formalism and its accompanying characteristic of division of labor. This scholar summed up the core of Weberian bureaucratic model as “the familiar picture of a hierarchy of authority organizing and in turn shaped by the division of labor and specialization of function with full time position in principle on merit, regular career ladders etc”. This model according to this scholar is indispensable to the understanding of a general organizational theory:Certainly any striving toward a general organizational theory (through the comparative route) cannot ignore bureaucratic theory; nor until a more accurate and revealing picture of the total organizational world is created, can anyone ignore bureaucratic theory if the objective is the central one of liberal education to understand one’s world in relation to oneself [6], [7].There are other or, many schools of thought within the classical theory of organization which need to be critically analyzed. These schools of thought have shown that the development of classical theory like other theories reflected the beliefs or values of its time regarding hoe organizations worked or should work. Consequent on this, “the first theories of organizations were concerned with the anatomy or structure of formal organization” [15]. This made the concern for organizational structure premised on the rational behavior of its human parts, the hallmark of classical organizational theory.The history of organizational theory shows that, its subject matter from the beginning, has been polarized by what Charles Perrow [13], [14] called the “forces of darkness” – (classical theory) – and the “forces of light” – (human relations school) – which falls within the parameters of the neo-classical doctrine. This polarization is far from being over because the asymmetrical standpoints of the two viewpoints in relations to organizations have generated various theoretical analyses of organization without any identifiable attainment of intellectual or philosophical consensus. According to this scholar, the forces of darkness within the developmental trend of organizational theory have been represented by those (mechanical school of organizational theory) who treat organization as a machine through its characterization of organizations in terms of “centralized authority, clear lines of authority, specialization and expertise, marked division of labor, rules and regulations and clear separation of staff and line”. And, that the forces of light have been represented by the human relations school which emphasizes people and such things as “delegation of authority, employees’ autonomy, trust and openness, concerns with the whole person and, interpersonal dynamics” [13], [14]. Putting these into a clearer perspective, Perrow [13], [14] argued that the threads of organizational theory started with the formulation of classical theories towards the end of nineteenth century and early part of the twentieth century. And, that these classical theories have been characterized as “the scientific management or classical management”. The dictatorial or regimented nature of the classical organizational theories were not without resentment from the beginning but “no effective counterforce (to the classical formulated position) developed until Chester Barnard’s (1938) work [4] entitled “functions of Executives”, which theorized organization as nothing but co-operative systems. This work stressed the existence of natural groups within the organizations and, the need for “upward communication”, “authority from below rather than from above” and “leaders who function as a cohesive force” [4]. The counterforce also came in terms of research orientation and outputs as exemplified by the publication of the outcome of the Hawthorne Plant experiment on productivity and social relations [24]. This is evident from the fact that “the research highlighted the role of informal groups, work restriction norms, the value of decent, humane leadership and the role of psychological manipulation of employees through the counseling system (which hitherto did not exist in the classical doctrine) (Emphasis mine) [24].After the intervention of the Second World War, the human relations movement came into existence using as its base, the insights of Barnard’s work [4] and the Hawthorne experiment [24]. Through its intensification the core of most of the researches already (then) conducted, was extended to organizations. Perrow [13], [14] summed up how the philosophy of human relations movement permeated the intellectual and research concerns of many theorists regarding the nature of organizations vis-à-vis the morale of those (employees) within them thus:As this work (human relations movement or efforts) flourished and spread, more adventurous theorists began to extend it beyond work groups to organization as a whole… (to the extent of knowing that) a number of things were bad for morale and loyalty of groups – routine tasks, submission to authority, specialization of task, segregation of task sequence, ignorance of goals of the firm, centralized decision making and so on – as well as bad for organizations. (Based on this), people began talking about innovation – the forces of light, of freedom, autonomy, change, humanity, creativity, and democracy were winning. Scientific management (i.e., classical doctrine) survived only in outdated text books (Emphasis mine).This scholar equally situated his articulation of Max Weber’s ideal bureaucratic model within this same perspective. He premised his position on the fact that Weber, in his theory of bureaucracy, clearly and only demonstrated that “bureaucracy was the most effective way of ridding organizations of favoritism, arbitrary authority, discrimination, payola and kick-backs, and yes, even incompetence” [13], [14]. Consequently, he explained the obsolescence of classical formulation (ideal bureaucratic theory) of Weber by articulating the fact that “Weber was all right for a starter, but organization had changed vastly, and the leaders needed many more means of control and more subtle - (human relations) – means of manipulation than they did at the turn of the – twentieth – century” (Emphasis mine) [13]. [14].In the same vein, Waldo [6], [7] criticized the classical theory of organization most especially the scientific management tradition. He stated his position buy arguing that “in many ways the classical theory was crude, presumptuous, incomplete, and wrong in some of its conclusions, naïve in its scientific methodology, parochial in its outlook. In many ways, it was the end of a movement, not the foundation of science”. He criticized the Weberian bureaucratic theory of the classical tradition both on scientific and moralistic grounds and placed it in the Paleolithic period (i.e., the Stone Age) in terms of scientific crudity.In contributing to the evolution of the organizational theory right from its historical roots, Henry [10] identified three models –close, open and the newer tradition – as sign posts for understanding the transformation the subject matter has gone through in terms of paradigms and, the characteristics of each state and the reason for transforming from one to the others. He referred to the classical tradition as the close-model of organizational theory which he equally called the “ideal type”. According to him, this model provides the hot bed for the take-off of the subsequent evolution of organization theory. And, that the model perhaps has had the largest influence on the thought and actions of Public Administrationists. This model has equally been variously tagged or called many names ranging from bureaucratic, hierarchical, formal, and rational to mechanistic [10]. Three schools have at least thrived within the realm of the close model. They include “the bureaucratic theory” [16], “Taylorism” [19], and “administrative management” [25]. This scholar emphasized that the close model has some principal features or characteristics which include the following:● Routine tasks occur in stable conditions.● Task specialization (i.e., a division of labor).● Means (or the proper way to do a job) are emphasized.● Conflict within the organization is adjudicated from the top.● Responsibility (or what one is supposed to do; one’s formal job description) is emphasized.● One’s primary sense of responsibility and loyalty are to the bureaucratic sub unit to which one is assigned (e.g., the accounting department).● The organization is perceived as a hierarchic structure (i.e., structure looks like a pyramid).● Knowledge is inclusive only at the top of the hierarchy (i.e., only the Chief Executive knows everything).● Interaction between people in the organization tends to be vertical (i.e., one takes orders from the above and transmit orders below).● The style of interaction is directed toward obedience, command, and clear super ordinate/subordinate relationships.● Loyalty and obedience to one’s superior and the organization are generally emphasized.● Prestige is internalized, that is, personal status in the organization is determined largely by one’s office and rank [25].This model is an ideal one to be striven for by organizations and, in practice organizations try to fulfill these characteristics/features even though, it may not be possible to put all of them into practice or actualize them. In an attempt to give relevance to the typology of the three schools of thought earlier identified, the scholar examined them respectively.

3.1.1. The Bureaucratic Theory (Max Weber)

- The German sociological writer, Max Weber, [16] was the foremost exponent of this school of thought [10]. Contemporary thinking on the subject matter of bureaucracy and its place in organizations is without any doubt predicated on the classical work of Max Weber in that his “analysis of bureaucracy which was first published in 1922” remains the “most influential statement or pronouncement and point of departure for all analyses on the subject” up till today [15]. Henry [10] identified the “bureaucratic theory” school of thought as the first within the “close model organizational theory”. The core of Weberian bureaucratic theory deals with the explanation of bureaucratic (formal) organizations. Thus, according to Shafritz and Whitbeck [15] “Weber used an “ideal-type” approach to extrapolate from the real world the central core of features characteristic of the most fully developed bureaucratic form of organization. Weber’s “characteristic of Bureaucracy” is neither a description of reality nor a statement of normative preference. It is merely an identification of the major variables or features that characterize bureaucracies”.According to this theory, the features/characteristics of bureaucracy include “hierarchy, promotion based on professional merit and skill, the development of a career service in the bureaucracy, reliance on and use of rules and regulations, and impersonality of relationships among career-professionals in the bureaucracy and with their clientele” [10]. This scholar asserts that the Weberian bureaucratic theory has been the most influential of all the schools (of thought) in the close model and, it most clearly represents the values of the close model [10]. As a matter of fact: Bureaucracy has emerged as a dominant feature of the contemporary world. Virtually everywhere one looks in both developed and developing nations, economic, social, and political life are extensively influenced by bureaucratic organizations. “Bureaucracy” is generally used to refer to a specific set of structural arrangements. It is also used to refer to specific patterns of behavior-patterns which are not restricted to formal bureaucracies. It is widely assumed that the structural characteristics or organization properly defined as “bureaucratic” influence the behavior of individuals - whether clients or bureaucrats-who interact with them [15].The predominant and prominence of the bureaucratic theory of organization notwithstanding, the theorists within the open model stream (along the evolutionary trend of organizational theory) have been very critical of the Weberian bureaucratic theory. The open model criticism of this theory has been summed up thus: “open model theorists dislike the rigidity, the inflexibility, the emphasis on means rather than ends, and the manipulative and anti-humanist overtones of Weberian bureaucratic theory” [15]. However, the criticisms of the Weberian theory have on their own been criticized in turn, because they “often have been overdrawn and certainly have not been leveled with Weber’s own social context in mind”.

3.1.2. Scientific Management- [talorism] (Frederick Winslow Taylor)

- This theory, propounded by Frederick Taylor represents another stream of the close model of organizations and its theoretical evolution and paradigm changes. This theory and its emphasis on time motion studies, flourished in the early part of twentieth century and, it remains very much relevant today in industry. The most firmly entrenched feature of this theory rests on its view of humanity through which it perceives “human beings as being adjuncts of the machine”, and, who must be made “efficient as the machines they operate” [19], [15]. The values and philosophy of the exponent for this theory were probably responsible for this perception. Frederick Taylor, the acknowledged “father” of scientific management found it necessary to articulate the fact that workers could be much more productive if their work was scientifically designed. He pioneered the development of “time- and – motion” studies. This was premised upon the notion that there was “one best way” of accomplishing any given task. Generally, “taylorism” sought to increase output by discovering the fastest, most efficient and least fatiguing production method. Once the “one best way” to do the job was (is) found the job of the scientific manager was (is) to impose the procedure upon his organization [15]. However, this “man as machine” orientation has been criticized and condemned through the emphasis that “man as machine model of the scientific management (school) has a distasteful aura. Men are not machines. They do not have array of buttons on their backs that merely need pressing for them to be machines” [10].

3.1.3. Administrative Management

- This represents another stream of thought on the issue of organizational theory within the close model. It is called generic management. Citing Luther Gurlick and Lyndall Urwick’s “Papers on science of Administration” [25] as a corollary to James D. Mooney and Alan C. Rieley’s “the Onward Industry” and “Principles of Organization” [26], [27], [28], Henry [10], argued that this theory represents an outstanding example of administrative management in public administration and its scholarship. According to him, it is the presumption of the theory of administrative management that “administration is administration wherever it is found” hence, its other title “generic”. This explains the devotion of the author’s energies to the discovery of “principles” of management that could be applied anywhere. This orientation was a by-product of the pervasive impact of “Taylorism” and its philosophy of “one best way” to accomplish a physical task which can be applied to any kind of administrative institution.The now famous mnemonic (i.e., memory improving formula) – POSDCORB which stands for the seven major functions of management – planning, organizing, staffing, directing, co-coordinating, reporting and budgeting was predicated on this orientation and philosophy. Even though, there are some points of divergence, administrative management is closer in concept and perceptions to Weberian bureaucratic theory than Taylorism because both bureaucratic theorists and administrative management theorists were, in the view of this scholar, principally concerned with the optimal organization of Administrators rather than that of production workers.The argumentative premise of the classical doctrine of organizational theory has been drastically affected by the constant changes occasioned by the continuous pursuit of knowledge through better theoretical explications, aimed at the expansion of its frontier. These constant changes which arose out of the growing concern for in-depth understanding of the actual state of things with organizational theory, have permeated the intellectual developments within the realm of organizational theory which is a component of public administration and Public Administration both of which have been analytically differentiated to enhance a proper analysis and understanding thus:Public administration (lower case) needs to be distinguished from Public Administration (upper case). Public administration (lower case) denotes the institution of public bureaucracy within a state: the organization structures which form the basis of public decision-making and implementation; and the arrangements by which public services are delivered. At the heart of publication administration is the civil service, but it also includes all of the public bodies at regional and local levels. Public Administration (upper case), as a sub-discipline of political science, is the study of public administration (lower case) by means of institutional description, policy analysis and evaluation, and intergovernmental relations analysis [29].As a matter of fact, the constant quest for better theoretical explanations and understanding on the subject matter of organizational theory over the years had been necessitated by the presumed inherent inadequacies of one theory and theorist by another. And, the classical theory of organization is not an exception to this inadequacy-syndrome:It would not be fair to say that the classical school is unaware of the day to day administrative problems of the organization. Paramount among these problems are those stemming from human interactions. But the interplay of individual personality, informal groups, intra organizational conflict, and decision-making processes in the formal structure appears largely to be neglected by classical organizational theory. Additionally, the classical theory overlooks the contributions of behavioral sciences by failing to incorporate them in its doctrine in any systematic way….. Classical organizational theory has relevant insights into the nature of organization, but its value is limited by its narrow concentration on the formal anatomy of organization [3].These inadequacies provided the basis for the emergence of the neo-classical theory of organization which “embarked on the task of compensating for some of the deficiencies in the classical doctrine. This trend notwithstanding, the tenets of the classical theory are still very visible in the succeeding approaches in the sense that “the neo-classical, as well as all other approaches to organizational theory have not discarded the tenets of the classical approach; they have merely adapted and built upon its foundations” [15]. The extent to which this has gone or become a reality in our world today, forms the core of the analysis in the next section below dealing with the neo-classical school of thought on organizational theory.

3.2. The Neo-Classical Doctrine

- The human relations movement forms the core of this doctrine. In spite of its different philosophical foundation and ideological leanings, this school takes the assumption of the classical doctrine about the “pillars of organizations” as given, but then, treats them as vulnerable to the modification of people “acting independently or within the context of the informal organization” (within the organization per se) [3]. This school of thought even though taken to be an “ideal type”, has been christened as “the open model” of organization truly x-raying its actual systemic existence. It has equally been called the “collegial model” [10]. Concretely put, this school of thought laid emphasis on, and, introduced the values of behavioral sciences into the theory of organization in ways conducive to the demonstration and measurement of the impact of human actions on the pillars of the classical doctrine. This is put into context by the fact that “the neo-classical approach to organization theory gives evidence of accepting classical doctrine but super imposing on it, modifications resulting from individual behavior, and the influence of the informal groups” [3].Talking about the adoption of the postulates of the classical doctrine by the neo-classical school of thought, the latter brought dynamism and understanding to the existence of the postulates within human organizations. For example, the monotonous and depersonalizing syndromes of the concept of division of labor were supplanted through the infusion of motivation, coordination and, leadership theories and techniques. The defects of the “scalar and functional processes” within the organizations as articulated by the classicalists, were identified and rectified by the neo-classicalists by tying human problems to the imperfections of the horizontal and vertical chains of command. In addressing the third pillar –structure of organization – which formed part of the core emphasis of the classical doctrine of organizational theory, the neo-classical theorists have delved into the provision of solution to its inherent problems within the organization in the area of relationship between “staff and line”. It has done this by emphasizing the need for harmony-rendering techniques like “participation, junior board, bottom-up management, joint-committees, recognition of human dignity and better communication” [3]. In the process, the existence and impact of informal organizations within and on the formal organizations as well as the causal factors of their emergence have been identified and thoroughly addressed. Through this it has been shown that, “in a general way the informal organization appears in response to the social need” – (the need of people to associate with others) [3].From the perspectives of the neo-classicalists, informal organization is a “series of more personal, primary relations that emerges within and influences the structures of formal organization” [30]. Its genesis is usually caused by the geography of physical location of employees within the organization which, in turn, determines who will or will not be in what group; symmetry or otherwise of occupation; range of interests, and special issues [30]. The first three – (location, occupation and, range of interest) – factors tend to produce more lasting groups while the fourth – (special issues) – often result in the formation of rather impermanent group since the resolution of such special issues tend to breed the dissolution of the group and reversal to the more natural group forms [30]. Examples of special issues usually include some of the formal prescriptions of organizations which are usually unrealistic with regards to the way(s) human beings actually behave [30]. This informal organization, according to Dressler and Willis Jr. [31], represents “bureaucracy’s other face”. Its informal ways of behaving are not codified in any book of rules hence, the informal structure is semisecret. Thus, what it is and what it is not have been emphasized by the neo-classicalists:Informal organization representing bureaucracy’s other face is by no means simply a negative factor, an instrumentality for circumventing bureaucratic rules and thus defeating certain aims of the bureaucracy. It often functions positively serving the official ends of the bureaucracy in the final result…..Business Corporation cannot be operated at maximum efficiency; Universities cannot be run adequately without the positive contribution of this other face [31].It should be emphasized however, that the non-injurious existence of the informal organizations to the formal organizations depends on the relationship between them and the formal organizations. This might only be possible if the relationship between the two is based on “live and let live philosophy” as opposed to “live and let die philosophy”. In other words, “working with the informal organization involves not threatening its existence unnecessarily, listening to opinions expressed for the group by the leader, allowing group participation in decision making situation” [3]. The semi-secret nature of the informal organizations notwithstanding, they have some characteristics which include:● Informal organizations act as agents of social control,● Informal organizations have status and communication system peculiar to themselves not necessarily derived from the formal system,● Survival of the informal organizations requires stable continuing relationships among the people in them etc., [3].The neo-classical doctrine has been variously categorized by scholars depending on their perspectives and/or ideological leanings. More importantly, like its predecessor, the classical doctrine, the neo-classical doctrine has been classified into three schools of thought - human relations, organization development and, organization as a unit functioning in its environment [10] which have been variously examined.

3.2.1. Human Relations School

- This, as the first of the three schools of the neo-classical doctrine considered variables which are on polar extremes to those of the classical doctrine. These variables include among others cliques, informal (group) norms, emotions, and personal motivations. In fact, the kernel of this school ironically took its roots from the 1927 (surprising) research findings of Elton Mayol and Fritz J. Roethlisberger in their series of studies (later known as the Hawthorne Experiment) [24] which has been earlier mentioned in this paper. These researchers predicated their experiment and its hypothesis on the core of Taylorism “that workers would respond like machines to changes in working conditions”.The crux of the Hawthorne experiment was based on the alteration of the “intensity of light available to a group of randomly selected workers” and, “on the idea that when the light became brighter, production would increase and when the light became dimmer, production would decrease” [10]. In this experiment the workers were told that they would be observed as an experimental group. The conditions were fulfilled by the researchers and, production followed the trend anticipated. Even, when the lights were dimmed to near darkness, production still kept climbing [10]. This tendency surprised the researchers to the point of disconcertedness. Hence, certain reasons which till today continue to give credence to the orientation and non-manipulative creed of human relations were identified as the cause of the experimental group’s indifference to the expectation of the researchers. These reasons which accounted for the ever increasing production level of the experimental group despite the researchers’ fulfillment – (i.e. turning up and turning down of the lights) - of the research conditions show that:● Human beings probably are not entirely machines (as claimed by Frederick Taylor and employed by Elton Mayol and F. J. Roethlisberger).● The Western Electric Workers at the Hawthorne Plant where the experiments were carried out were responding to some motivating variables other than the lighting conditions.● The Workers likely kept producing more in spite of poor working conditions because they knew they were being watched [10].Thus, the scholars and analysts within the human relations school of thought laid the foundation for workers improved productivity on factors extrinsic to the formalism of the work place. But then, the human relations school’s attack on the Hawthorne experiment that “the experimental group produce more because of relations among themselves, and management”, notwithstanding, the experiment nonetheless marked the beginning of the human relations movement as we come to know it today.Much of the emphases of human relations have been on the informal work group, what makes them work or not [10]. And, researchers in the school had equally investigated the managerial echelons as well, in addition to conducting research works on motivation and job satisfaction all of which had immensely contributed to the study of “public administration and Public Administration”. In most cases, human needs in organizations as well as the humanistic aspects of the organizations themselves, in the society have been given the pride of place. Notable among these are Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs, McGregor’s human side of enterprise which are later highlighted.Generally, the core of human relations school of thought is mainly concerned with participative decision-making, humanistic view of organizational men (i.e. workers in organizations) contrary to the manipulative, dictatorial or regimentational philosophy of the classical doctrine as espoused by some of the classicalists (e.g., Weber’s bureaucratic theory and Taylor’s scientific management). Even, the human relationists gave and still give prominence to the informal or small group aspects of workers’ existence within a broad organizational context. This has long been predicated on the view that organizational productivity could be improved or negatively affected by the impact of informal organizational relationship depending on the side turned to them by the formal organizational structure.

3.2.2. Organization Development (OD)

- This is the second of the three streams within the human relations school or open model of organization. Even though, there exists a great overlap between the tenets of Organization Development (subsequently referred to as OD in this paper), to the extent of almost questioning the need for its independent existence, it has been argued that OD “can be considered a separate school of thought because it attempts to go beyond the locus of small group theory and, it is almost missionary in its zeal to democratize bureaucracies” [10]. It has been defined as “a planned organization-wide attempt directed from the top that is designed to increase organizational effectiveness and viability through calculated interventions in the active workings of the organization using knowledge from the behavioral sciences [10]. Even though, OD, since its beginning in the late 1940’s had been applied in business organizations, its influence in public bureaucracies (i.e. public administration) gained increased acceleration in the 1960’s and, since then its “perspectives have generated a substantial technology for inducing desired effects” [32]. Generally, the goals of OD are broadly humanistic and they reflect the values of open model of organizations. Thus, it has been articulated that the mission of Organization Development (OD) is to:● Improve the individual member’s ability to get along with other members (which the field calls “interpersonal competence”).● Legitimate human emotions in the organization.● Increase mutual understanding among members.● Reduce tensions.● Enhance “team management” and “inter group co-operation”.● Develop more effective techniques for conflict resolution through non-authoritarian and interactive methods● Evolve less structured and more “organic” organizations [10].The advocates of OD believed that the pursuit and achievement of the foregoing mission or goals will render organizations more effective because the basic values underlining organization development theory is choice and, that various attempts have been made to maximize this through relevant techniques which include the use of:● Confrontation groups.● T-groups.● Sensitivity training.● Attitude questionnaires.● Third-party change agents in the form of outside Consultants.● Data feedback and,● The education of organizational members in the values of openness and participatory decision-making [10].

3.3. Organization as a Unit in Its Environment

- This is the third school of thought in the open model or neo-classical doctrine of organizational theory. The core of this school is emphasis on the organization as a unit vis-à-vis its environment. Notable contributors as scholars or researchers to this school of thought include Chester Barnard, Philip Selznick [3], [33], [34]. Simply put, this school of thought uses the organization as a whole in assessing the reciprocal impact of the organization and the environment on one another. Philip Selznick demonstrated this in his book on the establishment of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) through which he popularized the “co-optation concept”. It was through this concept which provided for the representation of members of the environment on the Board of Directors of the Tennessee Valley Authority that the TVA was able to pacify and gain support of the initially hostile and unfriendly environment in which it found itself as an organization at that point in time. The hallmark of this concept was “a give and take” philosophy.This school of thought has had a disproportionate impact on public administration because of its concern with the public (i.e. the environment) and its political relationship with the organization. Thus, the body of literature in this school of thought has been mainly concerned with the problems of public administration since the environment is indispensable to the success or otherwise of any organization within it.

3.4. Classical to Neo-classical Doctrine: Other Theoretical Efforts

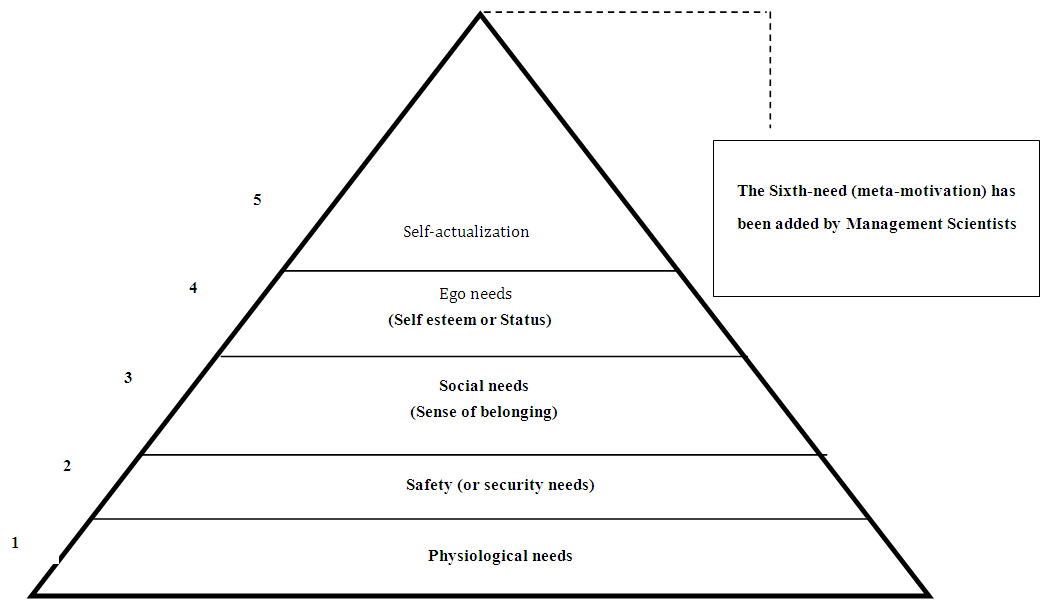

- Other theoretical efforts have been made to put into perspective the transformations which have taken place within organizations as a result of the paradigm changes associated with the developments concerning the theory of organization right from the classical period. These have been manifested concerning variables that are indispensable to the success or failure of our organizations over the time. The dichotomous explication of the concept of leadership in organization which even though, has long remained a dominant feature of all organizations, has clearly put into a clearer perspective the consequences of the evolution of organization theory over the years for our organizations and requisite workers’ morale and productivity [35]. This work has actually shown the effects of the paradigm shifts associated with the theoretical movement on the concept of leadership and its place in our organizations vis-à-vis the place of the individuals within them.In his classical work “the human side of the enterprise”, Douglas McGregor [35], examines the concept of the leadership using theories X and Y which over the years “have become such memorable theoretical constructs because they appear to be such polar opposites” [36]. The concept of Theory X (Dictatorial/regimental leadership or view of man) and Theory Y (Democratic or Liberalized view of man/employees in organization) form the core of Douglas McGregor’s work-“The Human side of Enterprise” [35]. Without doubt, this work at its inception represented one of the products of the then contemporary research in Personnel Management and organization theory. It emphasizes the humanistic side of organization’s environment. And, in it, McGregor criticized the dictatorial core of traditional theory of personnel management in relations to man’s existence within the organizational environment. He called the traditional theory of personnel management THEORY X which saw only THE MANAGER as an “active agent for motivating people, controlling their actions, modifying their behaviour to fit the needs of the organization: (Ibid.). From the perspective of McGregor, THEORY X has a pessimistic view of human nature. It views man as indolent, self-centered and, resistant to change and thus, must be repressed or forced to accept responsibility. This theory emphasizes nothing than “Management by direction and control”. In criticizing or condemning the THEORY X view of man (within the organizational environment) as archaic in terms of contemporary developments within organizational environment, McGregor utilized Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as the base [37]. This hierarchy which is shown in Figure 1 below:

| Figure 1. Figure showing the pyramidal explanation of Maslow Theory OF motivation) |

3.4.1. Theory X

- THEORY X view or conception of management’s task in harnessing or tapping human energy to organizational requirements can be propositionally trichotomized thus:(1) Management is responsible for organizing the elements of productive enterprise – e.g. money, materials, equipment and, people – in the interest of economic ends.(2) With respect to PEOPLE, this (i.e. organizing the elements of productive enterprise) is a process of DIRECTING their efforts, motivating them, controlling their actions, modifying their behaviour to fit the needs of the organization.(3) Without this active intervention by management, people would be passive – even resistant – to organizational needs. They must therefore be persuaded, rewarded, punished, (and) controlled. Their activities must be directed [35].In addition to this trichotomy, other widespread beliefs (and views of man) which form the core of this conventional theory X (of personnel management) include the following:(4) The average man is by nature indolent – he works as little as possible.(5) He (i.e. the average man) lacks ambition, dislikes responsibility and prefers to be led.(6) He is inherently self-centered, indifferent to organizational needs.(7) He is by nature resistant to change.(8) He is gullible, not very bright, the ready dupe of the charlatan (i.e. a fake) and the demagogue [35].According to McGregor these beliefs or views, form the core of “conventional structures, managerial policies, and practices. And conventional organizational programs have long been reflecting these propositions and assumptions. In highlighting how these beliefs have affected conventional organizational structures and policy orientations with respect to their (organizations) view of man, McGregor explained that management – (using these assumptions as guides,) - has conceived of a range of possibilities between two extreme approaches (hard and/or soft approaches). He explained that managements which share the theory X view of man and its tenets in carrying out the imperatives of this dictatorial / regimental or manipulative theory have been found to adopt either of the extreme approaches [35].Within the confines of the hard approach, there exist” methods of directing behavior involve coercion and threat (usually disguised), close supervision, tight controls over behaviors” [35]. But then, this approach is not without costs because, force which underlies it cannot but breed counter-forces, restriction of output, antagonism, militant unionism, subtle but effective sabotage of management objective. This approach is difficult and usually ineffective in times of full employment. On the other extreme is the soft approach, the methods - (direction) - of which involve permissiveness (on the part of the management), satisfying people’s demands, and achieving harmony in an attempt to make the employees tractable and accept direction. But then, part of the highlighted shortcomings of this approach range from its breeding of abdication of management to harmony, indifferent performance to expectation of more benefits (by employees) in return for less contribution [35].

3.4.1.1. Inadequacies of Theory X View of Man and Human Nature