-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2016; 6(5): 146-157

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20160605.02

Dynamic Entrepreneurial and Managerial Role in the Front End Loading (FEL) Phase for Sensing and Seizing Emerging Technologies

Chioma Anyanwu

Business School, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, P.R. China

Correspondence to: Chioma Anyanwu, Business School, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, P.R. China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Emerging technologies in the current era is characterised by the increasing network of digital devices and connectivity. Businesses around the world are challenged to keep up with these changes and to sustain their businesses at the same time. This poses challenges for the firm’s management team to identify the benefits of an emerging technology to the firm, when to adopt an emerging technology and or when to ignore it. In response to some of these challenges, business management teams are constantly in search of sustainable and flexible models that can easily adapt to technological evolution in their business environments. These models are used to plan on how to create, deliver and capture value from the emerging technology. This response approach requires that the firm’s strategy model is agile and resonant while the corresponding business model for value creation and capture is adaptable. This paper adapts the concept of the stage-gate methodology to analyse the robust planning activities in the early stages of sensing, seizing and transformation of an internet-enabled emerging technology from a firm’s external business environment. The main focus of this paper is on the ‘front-end loading’ phase of the process which basically incorporates strategic sensing activities of an emerging technological opportunity. The phase also includes business model adaptation activities that enable the firm to seize and transform the sensed opportunity. This phase is analysed to establish how firms can take advantage of their dynamic managerial and entrepreneurial capabilities to sense, seize and transform these technological opportunities into technologically-enabled value propositions. Some theoretical propositions are made on what business firms can do with their dynamic entrepreneurial and managerial capabilities to enable them sense and seize emerging technologies and areas of further research are also identified.

Keywords: Business Model Adaptation, Emerging Technologies, Dynamic Entrepreneurial Capability, Dynamic Managerial Capability

Cite this paper: Chioma Anyanwu, Dynamic Entrepreneurial and Managerial Role in the Front End Loading (FEL) Phase for Sensing and Seizing Emerging Technologies, Management, Vol. 6 No. 5, 2016, pp. 146-157. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20160605.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Today’s business environment is driven by rapid developments and ever-increasing penetration of digital technological applications (Sun, Yan, & Lu, 2012). In the current business era, the challenge is keeping up with the trend of technological evolution powered by the internet. This is further complicated by globalisation and free markets (Day, Schoemaker, & Gunther, 2004 Pg. 6). Typical examples include the Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology which has revolutionised the application of digital technology into previously non-digital products like household appliances. Similarly, the new generation of technologies like the social media and mobile technology are all enabling a new wave of change (Bolat, Aroean, & Robson, 2012; Jarvenpaa & Lang, 2005; Stern, Februaury 2013; Treem & Leonardi, 2013) at various levels within organisations and their industries. The advancements in technology enabled by the internet can prompt or create entrepreneurial opportunities for new or improved customer value propositions. For many organizations, the technology is moving faster than the company and its increased complexity is leading many organisations to opt to leverage their in-house competencies with externally available technological resources and capabilities (Ridder, 2013). In order for business firms to maintain their competitive advantage and to keep up with the trend, they need to identify possible business opportunities that come with these emerging technologies as well as how to exploit and manage them. This makes the internet-enabled emerging technologies to have a very broad impact on business organisations, thus affecting their business strategy, business models, organisational structure etc. In this regards, top management of firms are challenged on how to steer their organisations in the right direction while exploiting the potentials of the internet-enabled emerging technologies. These top managers need to understand their roles in taking the appropriate decisions on when, where and how to explore, exploit and manage these emerging technologies (Day et al., 2004 Pg. 6) to improve on the firm’s competitive advantage (Porter, 1985).

1.1. Background and Purpose of Paper

- Technological resources can be available in the macro-environment of a firm and its exploitation enables a firm to strategically position itself to compete for the present and prepare for the future (Hamilton, 1985). These external technological resources and capabilities include engineering and manufacturing know-how, technological methods and procedures which are acquired in a systematic way for the manufacture of a product, or for the application of a process or for the rendering of a service (UNCTAD). Also, these technological resources can create technological opportunities which can exist with ideas that have been created by new advances in a technology (Trimi & Berbegal-Mirabent, 2012). This is clearly seen with the internet which has enabled various opportunities in different fields including education, manufacturing, operations management, tourism, health care, telecommunications, engineering, knowledge management etc. It has created terms as ‘cloud computing’, ‘e-commerce’, ‘artificial intelligence’, ‘big data’, ‘internet-of-things’, ‘e-government’, ‘e-tourism’ amongst many others. Obviously, firms can decide to reinforce their internal innovative capabilities and other dynamic capabilities by importing these external technological opportunities which are then diffused, assimilated, communicated and absorbed into the organisation (Prahalad & Hamel, 2006). However, due to the interconnectedness nature of the internet, these internet enabled emerging technologies can be extremely volatile and fluid, with very short life cycles. This challenge has prompted various studies on how the current technological driving forces are having major impacts on the nature of products and services delivered by companies, its impact on the firm’s processes (Zhu & Fu, 2015), strategy (Hamilton, 1985; Jansson, 2008a; Jarvenpaa & Lang, 2005), business model (Adner & Kapoor, 2010; Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002; Chesbrough, 2007; Sun et al., 2012) and dynamic capabilities (Danneels, 2007; Narasimhan, Rajiv, & Dutta, 2006; Roberts, 2009; Teece, 2010b).These advances in information and technology have triggered the increased recent interest on studies of business models (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010). In this regards, there is a classic argument that business model transformations that lead to innovation, enables a firm to commercialize technological innovations (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002; Chesbrough, 2007). Currently, the Internet of things inspires a wealth of innovative business models, which forces organizations across industries to adjust their strategies in order to succeed in digital market environments (Sun et al., 2012). Several scholars agree that the Internet, together with related advances in information and communication technologies (ICTs), acts as a catalyst for business model experimentation and innovation (Timmers, 1998, Amit & Zott, 2001, Afuah & Tucci, 2001). Some scholars have also identified the need for business organisations to create an overarching requirement for business model innovation (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013; Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002; Sun et al., 2012) to enable the firm create and deliver valuable products and services that evolve with technological trends.Although there is no generally acceptable definition of a business model, this work will adopt (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010)’s view of a business model as a reflection of the firm’s realised strategy. Two main streams of the business model concept as identified by (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013) are: business model as part of strategy lexicon and intertwined with technology (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Zott & Amit, 2007) and business model as a potentially separate stand-alone entity (Teece, 2010a). A common theme across all publications on business model as a new unit of analysis, includes it with a holistic perspective on how business activities carried out are important for value creation (Zott, Amit, & Massa, 2011). With regards to value creation and value capture, how an organisation chooses to respond to its environmental challenges depends on its strategic intent, and its ability to adapt or reinvent the wheels of their business models (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010). This is a challenge for most business managers as they struggle to keep up with the trend especially as they scan and integrate these externally available technologies into products and services to improve on their value propositions. This implies that business managers need to constantly update their skills, acquire new ones, develop new ways of thinking and also device innovative managerial approaches to cope and succeed. This paper aims to adapt the stage-gate process (Cooper, 2008) approach for the sensing, seizing and transformation (re-configuration) (Teece, 2007) of value from an internet-enabled emerging technology. The main focus of the paper is on the front end loading phase. The front-end loading phase involves the planning of activities, resources and systems for value creation and seizure. The aim to is to identify the role of entrepreneurial capabilities (Fernald Jr, Solomon, & Tarabishy, 2005; Zahra, Abdel-Gawad, Svejenova, & Sapienza, 2011) for sensing emerging technologies and the role of dynamic managerial capability (Adner & Helfat, 2003) for seizing and transforming the technological opportunities from its external business environment, to create products and services that meet the needs of the customers. The work follows previous studies that have linked a firm’s business model to its strategy and operation (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010; Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002). However, this work takes a slightly different approach in contributing to the body of knowledge that links technology and business models. This work tries to establish a process driven approach on how the a firm’s business model (linked to the firm’s strategy and operations) can be used in gated phases to sense, seize and transform an internet-enabled emerging technology into a product or a service that meets the needs of consumers. The main focus of the process described in this paper is on the role of dynamic entrepreneurial and managerial capabilities required to carry out the activities in the front-end loading phase. The front-end loading phase involves a lot of planning activities which requires strategic agility and flexible business models that can be adapted.

1.2. Scope of Work

- The researcher makes no attempt to build a formal theory but to contribute to the body of literature on dynamic capabilities and business model. The research will make an attempt at using existing theories, concepts and conceptualisations from different fields on strategy, business model and dynamic capabilities to analyse the topic as an issue of ‘fit’ between an organisation and its relative business environment. The reviewed literature provides a better understanding on how firms utilise their entrepreneurial and managerial capabilities to sense, seize and transform technological opportunities into value, through controlled responses to its business strategic change options (Jansson, 2008a) and business model adaptations (Saebi, 2014). Due to the fact that there is a lack of consensus on the definition of dynamic capabilities as well as business models (Demil & Lecocq, 2010) and no clear cut boundary between them, there exists overlaps in language and concepts from these various fields of study but they serve unique and complimentary roles in exploring and exploiting internet-enabled emerging technologies from an external business environment to create and deliver value.

1.3. Paper Design and Structure

- The paper is structured to firstly review the concept of stage gate process, internet-enabled emerging technologies. It then looks at the dynamic capabilities and its clusters of ativities for sensing, seizing and transformation. It hen tries to relate these clusters to strategic agility, strategic resonance and business model adaptation. Subsequently, using a stage-gate process approach, the paper develops a graphical representation of the stages for sensing, seizing and transforming internet-enabled emerging technologies into a value propositions. The work focuses on the front end loading phase to identify the role of dynamic entrepreneurial and dynamic managerial capabilities for sensing, seizing an transforming internet-enabled technological opportunities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Stage-Gate Model

- The stage gate model (Cooper, 2008) is native to product development literature and is used as a guide to develop a structured process model for product development. The system is a comprehensive, integrated, evolving system that depicts a conceptual and operational blueprint built on best practices and success drivers that depicts a linear system with series of stages to effectively and efficiently manage a product innovation process. Each stage has a set of prescribed, cross functional and parallel running activities to gather critical information that may help reduce unknowns and uncertainties. The stages are linked by decision gates which focus on the performance of the process at that point, while also taking into consideration risks, investment decisions, available resources etc. This is to enable the decision makers to decide if to continue with a plan, or to put in on hold, or to revise the previous stage or to kill the plan, if it will not be viable in the current context and time.

| Figure 1. Overview of the Stage Gate Process |

2.2. Internet-Enabled Emerging Technologies

- The advent of the internet has triggered many opportunities for firms on the global stage. Business firms convert these opportunities into products and services that meet the needs of consumers. These internet-enabled emerging technologies have created innovative outcomes and interests in robotics, genetics, nano-technology, artificial intelligence, big data, informatics, mobile phones devices, digital manufacturing equipment etc. These internet-enabled emerging technologies which come with changes to existing technology can render the existing resources and capabilities of firms obsolete while some can enhance the firm’s resources and capabilities (Tushman & Anderson, 1986). In general, emerging technologies are characterised by its disequilibrium, profound ambiguity and its frequency of change (Day et al., 2004). The successful exploitation of emerging technologies requires a coherent strategy for manoeuvring through environmental uncertainty as well as making the right choices on the initiatives that support the emerging technology. It also involves establishing possible alliances to pursue the chosen strategy and to develop the required human capabilities. Firms need to have the capability to carry out a detailed analysis on the impact of an emerging technology on its resources and capabilities. Thus it is important to identify at which level (component or architectural), the internet-enabled emerging technology will be utilised (Henderson & Clark, 1990). For example, an architectural change requires a major reconfiguration of a company’s strategy and organisational structure which basically involves reconfiguring the firm’s business model with available dynamic capabilities.

2.3. Dynamic Capabilities for Sensing, Seizing and Transformation

- Dynamic capabilities consist of capabilities that aid the development, assimilation, exploitation, recombination and reconfiguration of a firm’s competences to address the changes in business appropriately (Augier & Teece, 2009; Teece, 2009). They are firm specific as they are embedded in the firm’s processes and routines and cannot be easily transferred (Arend & Bromiley, 2009; Lavie, 2006; Rindova & Kotha, 2001; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997a). The successful combination of dynamic capabilities with strategy (Rumelt, 2011) enables a firm to deliver on its business model by meeting the needs of the consumers with the right goods and services, while also positioning itself for the exploitation of technological and competitive opportunities (Teece, 2012). To achieve all these, top management of firms utilise their competences to develop scenarios on how best to pioneer a market or a new product category (Teece, 2012).(Teece, 2007) identifies three clusters of dynamic capabilities necessary to sustain superior enterprise performance. In relation to activities, these include: identification and assessment of an opportunity (sensing); the mobilization of resources to address an opportunity and to capture value from doing so (seizing); and the continued renewal (transforming) of resources and capabilities. These clusters are based on analytical dimensions for the ability to sense and shape opportunities and threats, ability to seize opportunities and the ability to maintain competiveness by combining, enhancing, protecting and reconfiguring a firm’s tangible and intangible assets. These are technically, adjustments which must be performed expertly by managers, if the firm is to sustain itself as markets and technologies change in the environment. The dynamic capabilities that make it possible to succeed in this endeavour involve good strategising as well as good execution of organisational activities that correspond with the chosen strategy. Some creative managerial and entrepreneurial acts aim to achieve semi-continuous asset orchestration and renewal. These are strategic by nature and involves human beings using knowledge to create things that do not yet exist but should (Amit & Zott, 2014; Sirmon, Hitt, Ireland, & Gilbert, 2011) or changing existing situations into desired ones (Amit & Zott, 2014). Some firms will be stronger than others in performing some or all of these tasks depending on the combination of their entrepreneurial and managerial capabilities, available within the firm. Thus growth capabilities are an outcome of leadership behaviours and management activities combined. This is further developed through the result of interactions and complementarities among individuals, processes, and structures (Kotter, 2013).

2.4. Sensing For Internet-Enabled Emerging Technologies

- Opportunities can be detected if entrepreneurs have differential access to existing information (Kirzner 1973 in Teece, 2007); or new knowledge or new information can create opportunities (Schumpter 1934 in Teece, 2007). Opportunity identification involves probing customer needs, technological possibilities, understanding latent demand, understanding the structural evolution of industries and markets, competition etc. (Al‐Aali & Teece, 2014) states that sensing is an inherently entrepreneurial set of competencies that involves exploring technological opportunities, probing markets and listening to customers along with sensing the other elements of the business ecosystem. This implies that firms need to have the capabilities to be proactive and/or reactive to varying factors in its business environment. The ability of firms to identify and recognise new opportunities require dynamic capabilities on knowledge, processes and techniques to aid in the identification of new market segments, changing customer needs, customer innovation, emerging technologies (Danneels, 2008) etc. These set of abilities also enables the firm to strategically position itself in its business environment for external changes in the business environment. This implies that firms need to be strategically agile to cope with changes in its business environment.Strategic Agility and Resonance Factors in a firm’s external business environment that prompts strategic changes within the organisation, include changes in demand, science and technology, availability of raw materials, and government policy amongst many others (Jansson, 2008a). But a firm’s conceptualization of its environments as a dynamically heterogeneous one, suggests a need for developing a corresponding conceptualizations of strategy that can help the firm sustain its competitive advantage (Afuah, 2015; Jansson, 2008a). A firm’s top management needs to be strategically agile by sharpening their perception of business opportunities. They need to intensify their awareness and attentiveness to a business opportunity (Doz & Kosonen, 2010), especially with new wave powered by internet-enabled emerging technologies. Business decision makers need to be able to make bold decisions and take radical steps to explore and exploit internet-enabled emerging technologies, by harnessing their internal capabilities to reconfigure capabilities and redeploy resources rapidly (Ridder, 2013). However, business organisations also need to establish a strategic resonance, which is about ensuring that a firm develops and protects its key capabilities (Brown & Fai, 2006) that can be used to exploit the identified technological opportunities. The concept of strategic resonance ensures a continuous linkage and harmonisation between the market, the firm’s strategy and the firm’s functions and related capabilities. This dynamic process requires simultaneously managing the capabilities required to exploit market opportunities, the cohesion of functions and the strategic alignment within them. It also involves aligning opportunity sensing capabilities with the capabilities for competing in specific markets. The ability of business organisations to achieve this harmonisation efficiently and effectively helps the organisations to achieve a competitive advantage and can be achieved through the dynamic renewal of the firm’s business model which is also an outcome of the firm’s strategic agility (Doz & Kosonen, 2010).

2.5. Seizing and Transforming Internet-Enabled Emerging Technologies

- When a new technological opportunity is sensed, it must be addressed through new products, processes and services (Teece, 2007). This involves maintaining and improving technological competences and complementary assets. It also involves the selection and creation of a business model that defines the firm’s commercialisation strategy. The business model implicates the processes and incentives as well as its alignment with the physical technology. Firms are continuously subjected to external environmental pressures and need to adapt their business models to preserve their relevance ((Müller & Vorbach, 2015; Wirtz, Pistoia, Ullrich, & Göttel, 2016). Given the increasing complexity of the technological and market environment in the current era, firms of every size, age and industry that aims to keep succeeding in their businesses should become more agile in adapting the whole business model of the firm to external contingencies (Chesbrough, 2010; Demil & Lecocq, 2010). However, these firms must retain their core business propositions even as they adapt their business models so that they maintain their core competitive advantages. The successful sensing and seizing of a technological opportunity can lead to enterprise growth and profitability and profitable growth in turn leads to the augmentation of enterprise-level resources and assets (Teece, 2007). To successfully achieve this, firms need the capability to recombine and reconfigure their assets and organisational structures as the enterprise grows and as the market and technology evolves. This capability is also required for operational efficiency. (Andries, Van Looy, Lecocq, Debackere, & Indicatoren, 2007) are of the view that business models should be adjusted in parallel to the firm’s life cycle evolution because they are opportunity facilitators for entrepreneurs, which further represent the cognitive link between the business appraisal of the opportunity and its exploitation (Fiet & Patel, 2008). Thus, it is possible to envision a business model life cycle involving periods of specification, refinement, adaptation, revision and reformulation. Hence this research work is of the view that the seizing and transformation phase of a business opportunity is the adaptation of a firm’s business model to satisfy its customers and capture value (Al‐Aali & Teece, 2014) within a specified period.Business Model AdaptationIn this context, a firm’s business model is a reflection of the firm’s realised strategy (Al‐Aali & Teece, 2014; Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010; Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002; Doz & Kosonen, 2010). Other scholars of similar perspective (Richardson, 2008) view a firm’s business model as how the activities of the firm work together to execute its strategy. Also in relation to strategy, 10 gives some insight on business model, as a firm’s management’s hypothesis on what customers want, and how an enterprise can best meet those needs and get paid for doing so. Business models need to be assessed to establish their strategic fit and its potential to enhance the firm’s competitive advantage. (Saebi, 2014) further introduces the concept of business model change capability which is defined as the firm’s capacity to adjust, adapt and innovate its business model in the face of environmental dynamics. This is to overcome core-rigidities of the firm’s existing business model and to implement change processes in a structured and systematic way. In summary, scholars that try to relate the business model concept to strategy are interested in explaining a firm’s value creation, its performance and competitive advantage (Zott et al., 2011). This perspective prompts this research work’s approach, to apply the business model concept as a component that links both strategy and operational effectiveness for value sensing, seizing and transformation of technological opportunities and other business opportunities. The ability to attain alignment with the business environment is the main motivation behind business model adaptation (Saebi, 2014). The various dimensions of the business model can be affected simultaneously with varying degrees of radicalness as it is being adapted to suit changes in its business environment. (Saebi, 2014) summarises that various dimensions of a business model change because a firm’s business model is a process of continuous selection, adaptation and improvement, to fit a changing environment ((Doz & Kosonen, 2010, Demil & Lecocq, 2010, Teece, 2010, Casadesus & Ricart, 2010, Ho, Fang & Hsieh, 2011) in Saebi, 2014). This implies that the business model has become an important lever for enhancing a firm’s ‘ecological fitness’ (Amit & Zott, 2014) to enable it offer solutions that meet customer needs and make money from the offerings (Teece, 2010a). Thus adapting a business model reflects purposeful changes made in response to changing environmental conditions (Saebi, 2014). A firms’ business model can be used to convert technological opportunities into economic growth through the firm’s customers and markets (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002) and it can be adapted to align with reality in the context of the business in a particular environment. From this perspective, it is implied that value can be realised from an internet-enabled emerging technology. The value identified and created from the internet-enabled technology translates into the firm’s customer value proposition which is targeted at the right market segment that is willing to pay for the offering. The firm generates revenue by monetising its customer value propositions that it offers to its customers. To beat competitions, firms need to figure out how to grow profitably, thus they develop the right capabilities (which includes the right resources/assets and activities) that use the resources/assets to create and capture value. This briefly summarises (Afuah, 2015)’s components of a business models system of customer value proposition, market segment, revenue model, growth model and capabilities, which have unsymmetrical linkages. In general, capabilities are central to every business model and the existence of dynamic capabilities enables a more proficient way of changing business models (Müller & Vorbach, 2015), which can potentially lead to tapping into internet-enabled emerging technologies. The extent of value created and captured by a firm depends on the quality of the available resources, capabilities and which activities are performed to build and/or to transform the resources. It also takes into consideration who performs the activities, when the activities are performed, where they are performed and how they are performed. Thus at the core of the capabilities and activities are the people who make and allow changes to business models (Afuah, 2015). The top management team of firms are essential for eliminating barriers to change and enhancing the opportunity to implement a new or modified business model successfully. However, managers themselves can be a barrier to change if they are not skilled and willing to change the existing business model (Massa & Tucci, 2013). From this perspective, a business model for a firm’s top management can be a cognitive structure that provides a theory on how to set boundaries to the firm, how to create value and how to organise the internal structures and governance (Doz & Kosonen, 2010; Zott & Amit, 2010) to give the firm its competitive advantage. Thus the next section looks at the dynamic capabilities of a firm from the perspective of dynamic entrepreneurial capability and dynamic managerial capability. As identified earlier, these two capabilities are required for sensing, seizing and transforming internet-enabled emerging technologies within any business organisation.

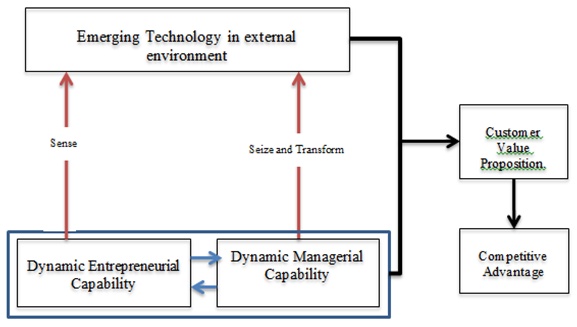

2.6. The Role of Dynamic Entrepreneurial and Managerial Capabilities in Sensing, Seizing and Transforming Business Opportunities

- In general, entrepreneurial managers face rapidly changing and highly uncertain environments, and as a result, they must be able to respond quickly and effectively to extensive changes in a wide range of external conditions, hence this work introduces the term’ dynamic entrepreneurial capability. The term 'dynamic' refers to the capacity to renew competences so as to achieve congruence with the changing business environment where certain innovative responses as time-to-market and timing is critical; or the rate of technological change is rapid, and business environment is uncertain (Teece et al., 1997a). The concept of ‘dynamic managerial capabilities’ was introduced by (Adner & Helfat, 2003), and highlights the importance of managers’ strategic decisions to ‘build, integrate, and reconfigure organizational resources and competences’. These managers make decision options for producing significant outputs of a particular type (Winter, 2003), and renew the firm's competences so as to achieve congruence with the changing business environment (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). The dynamic managerial capabilities can be used to identify and seize technological opportunities, diagnose threats, as well as prepare the organisation by directing (and redirecting) resources according to a policy or plan of action (Teece, 2012), and possibly also reshaping organizational structures and systems so that they create and address technological opportunities and competitive threats (Argote & Ren, 2012). Visionary companies understand that emerging technologies in their early stages can become the cornerstone of an industry, thus managers need foresight and imagination to analyse and understand the ultimate potential of the emerging technology. The sensing activities involves exploring technological possibilities, probing markets, listening to customers, scanning the business environment in search of potential business models and to develop innovative options for strategic resonance. The strategic decisions made by business entrepreneurial managers reflect the perceived or actual need for exploiting a business opportunity. The business environment and the forces that push and pull a firm are challenges for managers to deal with. Managers need to plan, organise, control and lead processes, systems and people within their organisations to enable them achieve a certain goal. The managerial perception of both its internal and external environments impact on their decisions to use different levels of dynamic capabilities (Stimpert & Duhaime, 1997). In summary, the sensing, seizing and transformation of opportunities can be achieved by the active intervention of human skills and knowledge thus requires good managers. Entrepreneurial managers and business leaders are key elements to sensing, seizing and transformation of technological and non-technological opportunities inside and outside the organisation and for developing new ideas and insights (Al‐Aali & Teece, 2014; Amit & Zott, 2014).

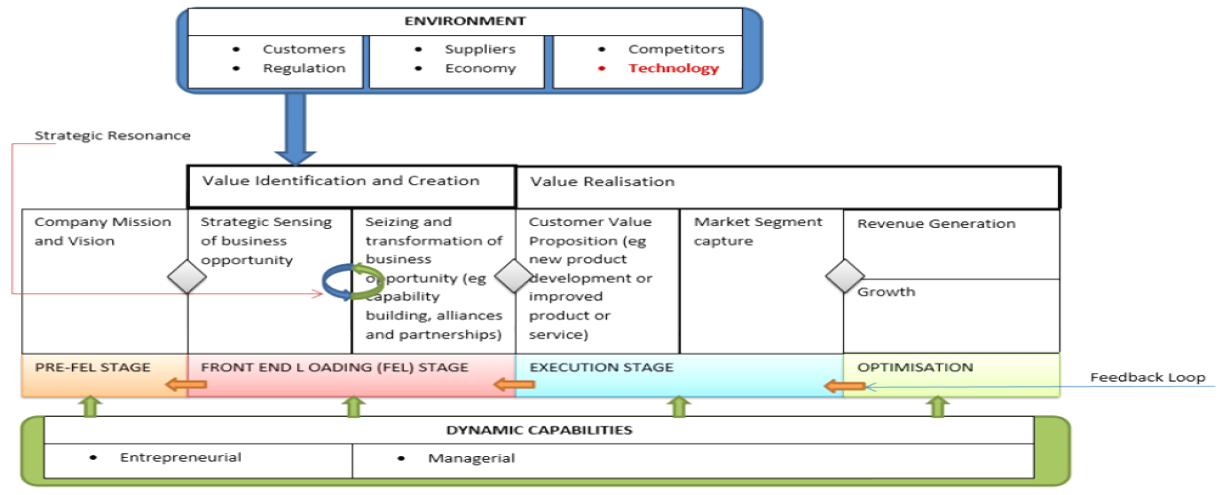

3. An Integrated Approach or Sensing, Seizing and Transforming Internet-Enabled Emerging Technologies

- This section will attempt to conceptualise a process based framework that outlines the activities of the entrepreneurial leaders and decision making managers in sensing, seizing and transforming internet-enabled emerging technologies to create new value propositions. To put things into perspective, the work first presents a high level process flow diagram (as represented in Fig 2.) for sensing, seizing and transforming internet-enabled emerging technologies, based on the literature gathered so far. Then it focuses on the Front-end loading phase with regards to the activities of the dynamic entrepreneurial and decision-making managers in identifying, seizing and transforming internet-enabled emerging technologies into value propositions.

| Figure 2. Integrated Stage gate process for Sensing, Seizing and Transforming business opportunities (own representation) |

3.1. Front End Loading Stage: Value Identification and Creation

- The front end loading stage of the proposed framework deals with the activities required for value identification and value creation. This includes the activities required for sensing business opportunities, as well as seizing and transforming these opportunities.

| Figure 3. Role of Dynamic Entrepreneurial Capability and Dynamic Managerial Capability in strategic sensing and business model adaptation |

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- In the current era of internet-enabled business challenges, firms need to detect and understand some of these challenges as opportunities. Business firms need to develop the right capabilities which enable the flexibility of its strategy and business models. This is to enable the firms to sense, seize and transform business opportunities. The ability of a firm to adapt, develop and reconfigure its extant resources and capabilities to a sensed business opportunity requires dynamic entrepreneurial and managerial capabilities as they have an increasing number of alternatives for how to structure their value chain as well as their supply chains (Amit & Zott, 2014; Porter, 1985). In summary, the distinctive function of dynamic managerial capabilities lie in recognising, realising and sustaining the sources of value through adaptation of business model (Amit & Zott, 2014). Dynamic managerial skills and entrepreneurial leadership supported by a good corporate culture that appreciates change, are important capabilities for sensing, seizing and transforming internet-enabled technological opportunities into value. Entrepreneurial capabilities for the strategic sensing of the potential value of an internet-enabled emerging technology, is an iterative, creative process that organises resources and capabilities that can better reposition or defend the firm’s position in the market. By building on an assessment of opportunities, risks and the market environment, an organisations’ strategy determines the appropriate mix of products, processes and services to achieve the desired outcomes, provides the specifics of how the firm will deploy its scarce assets to implement a matching business model that will generate the greatest benefits to customers and other stakeholders, The strategic analysis carried out by top management differentiates the potentials of the emerging technologies for various market segments and ensures that the planned positions are defensible. If strategic sensing managers have little or no skill in planning on how to seize and transform an internet-enabled technological opportunity, then the firm struggles on the competition landscape. The availability of other dynamic capabilities within the firm combined with the externally sensed technological opportunity helps entrepreneurial managers to develop strategies that will aid the successful adoption of the identified technological opportunity.

4.1. Managerial Implications

- The ability to generate multiple strategic frames for a business model is rare and valuable as it requires cognitive diversity among executives. Managers need to create and enable an environment in which tolerance for failure excels to an extent, but must be accompanied with a lessons learnt approach whereby diagnosis of the possible reasons of failure are established. Strategy teams need to be flexible with decision making to adapt to situations, thus leaders need to be adaptive themselves. Business managers may need to change their mind-sets to enable them successfully exploit emerging technologies.

4.2. Further Research

- Managers and entrepreneurs can be fallible hence the reconfiguration of resources may also result in unfavourable outcomes and can even destroy valuable extant capabilities (Sapienza, Autio, George, & Zahra, 2006) thus, it will be important to identify forces that can impede the successful exploration and exploitation of a technological opportunity into a value proposition that meets customer needs. These can be researched on the leadership styles of the managers and the role of emotional intelligence in exploiting technological opportunities.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML