-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2016; 6(4): 89-102

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20160604.01

Managing State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and Parastatals in Zimbabwe: Human Resource Management Challenges - Drawing Lessons from the Chinese Experience

Rangarirai Muzapu, Taona Havadi, Kudzai Mandizvidza, Niu Xiongyi

Business School, University of International Business and Economics (UIBE), Beijing, China

Correspondence to: Rangarirai Muzapu, Business School, University of International Business and Economics (UIBE), Beijing, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The paper establishes how different human resource management styles and practices can be implemented to enhance effectiveness of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). It largely focuses on Zimbabwe’s state enterprises human resource management challenges and highlights the impact of such challenges on production and productivity. Furthermore, the paper proffers possible solutions by drawing from applicable and implementable lessons from the Chinese state enterprise management reforms. A survey and document analysis approach was used to gain insights into human resource management styles and challenges in Zimbabwe’s state enterprises. Desk research method was used to collect data on the Chinese side. The study found that weaknesses in governance structures were the root cause of the poor performances affecting state enterprises in Zimbabwe. Some identified weaknesses included the lack of quality leadership, poor work ethic, corruption, high human resource turnover, lack of performance-based reward practices, overstaying and intra-swapping of leadership in parastatals. It was noted that in the absence of sound corporate governance reforms, the state enterprises in Zimbabwe may not perform optimally. The researchers agree with other scholars that corporate human resource governance is dynamic and evolving. It then requires full commitment and strict adherence to effective management principles and practices. However, further research may be necessary to understand the reasons for human resource governance failures in SOEs in developing countries.

Keywords: State Owned Enterprises, Parastatal, Corporate Governance, Board of Directors, Cabinet

Cite this paper: Rangarirai Muzapu, Taona Havadi, Kudzai Mandizvidza, Niu Xiongyi, Managing State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and Parastatals in Zimbabwe: Human Resource Management Challenges - Drawing Lessons from the Chinese Experience, Management, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 89-102. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20160604.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

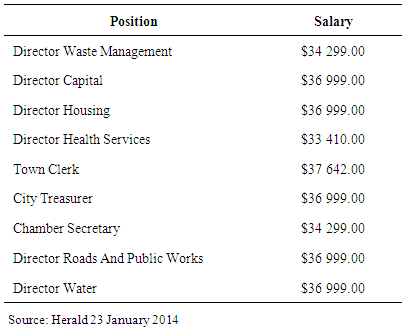

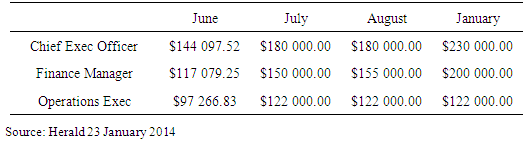

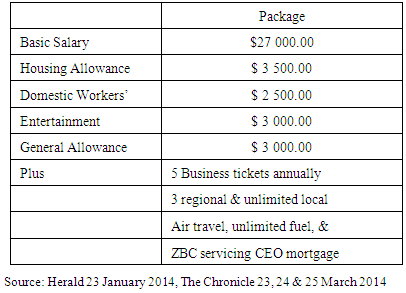

- State owned enterprises (SOEs) and parastatals play a key role in promoting socio-economic development by providing a wide range of products and services to the nation. They are critical in the provision of public and social infrastructure services essential to humanity such as food, water, electricity and health to mention just a few. In the 1990s, state enterprises and parastatals in Zimbabwe accounted for over 40% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In recent years, however, the sector’s contribution to the GDP has been declining gradually due to a myriad of factors such as undeveloped infrastructure and the shortage of key technologies (Ministry of Finance, Mid Term Fiscal Policy, 2015). Weaknesses in governance structures have also contributed to the declining performance in the sector. Notwithstanding the effects of the harsh domestic or external business environment such as the global recession, some SOEs, such as Air Zimbabwe, Civil Aviation Authority of Zimbabwe (CAAZ), National Railways of Zimbabwe (NRZ) and the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC), have since become technically insolvent, and many a time they fail to meet even their contractual obligations to their employees. They owe their continued existence to government bailouts, a development which exerts more pressure on the already strained national purse (Ministry of Finance, Mid Term Fiscal Policy, 2015).In 2014, Zimbabwe’s Auditor-General exposed evidence of corporate management challenges in SOEs and parastatals, especially in terms of corrupt tendencies and financial scandals. The Auditor-General found out that some Chief Executives, senior SOE employees and politicians were milking the organizations by awarding themselves unjustifiably hefty salaries and allowances, flouting tender procedures, and diverting organizational property for private benefit. This was found to be the case at ZBC, NRZ, Zimbabwe United Passenger Company (ZUPCO), Air Zimbabwe and the Premier Service Medical Aid Society (PSMAS). (See appendix Table 1, 2 and 3). The cases revealed that SOEs and Parastatals were inundated with structural and organizational problems, incomplete accounting and financial statements, illegal governance practices and poor management of investment decisions (Ministry of Finance: Auditor General Report, 2015). The interference by politicians in the internal affairs of SOEs and parastatals was also found to have compromised government’s will and resolve to deal decisively with the corrupt practices in the sector. It is noteworthy that, to a large extent, sound and efficient management of organizations depends on the effectiveness of control frameworks, and professionalism, experience, competence, and qualifications of those in management, and accountability, most of which were found to be lacking in Zimbabwe’s SOEs. It therefore follows that the reform of human resource management practices and systems is key to the revival of SOEs in Zimbabwe. Wright (2003) noted that senior human resource leaders and executives have a fiduciary responsibility to shareholders and a moral responsibility to employees. This is what it should be in any enterprise, anything short of that is dereliction of duty and is costly to the enterprise. It was therefore necessary to examine why SOEs and parastatals in Zimbabwe were failing to fulfill their mandates, so as to rectify the situation and cause the sector to fulfill its responsibilities. Zhou (2012) observed a tendency by SOEs executives, boards and employees to exploit systemic gaps and/or blind spots within organizations, such as the undefined (authority and responsibility) boundaries between the minister responsible for the company, the board of directors and the chief executive to fleece the organization. Predatory leaders thus take advantage of such overlapping and undefined responsibility boundaries for their own benefit.After highlighting the managerial weaknesses in SOEs and parastatals in Zimbabwe, the researchers proffered possible solutions by drawing applicable lessons from the management styles in Chinese SOEs and parastatals. The idea is to facilitate the transformation of Zimbabwe’s SOEs and parastatals to regain competence and contribute significantly to sustainable national development and growth.

2. Why Focusing on Human Resources?

- Himmelberg (2002) and Coles, Lemmons and Meschke (2003) highlighted the effect of human resources in the development of an enterprise. They pointed out that effective human resource systems and practices assist in enhanced management of firms. This in turn can lead to greater investment, company growth and resource employment, and improved operational performance through better business management which creates wealth. Furthermore, it was noted that such practices and systems reduce risks of skills crisis, and they improve relationships among all stakeholders, which are all factors that would assist in improving labor and social relationships as well as other areas of significance in an enterprise.

3. Why the Study about China’s Human Resource Management Practices?

- China has transformed over the years to become the world’s second largest economy. It now boasts of several large manufacturing and high-tech industries as well as large and competent state enterprises. The economy has more than 155 000 SOEs though some restructuring exercise in the form of merging and disposing entities is ongoing (Miao Wei, 2014). Miao Wei (2014) pointed out that proper management and organization of the enterprises largely enabled the successful transformation. Furthermore, the development was aided by the Chinese government’s model of a market-socialist ideology that apart from exhibiting some Chinese characteristics is also supported by the construction of vital infrastructure. Miao further noted that China has witnessed significant improvements over the years in the management and supervision of state enterprises. It can be observed that China’s state sector remains significant, relevant, and powerful and continues to dominate on the market.The 2015 National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) work visit presentation in Zimbabwe, state that since the beginning of reform and opening-up in 1978, China’s SOEs and parastatals have undergone significant transformation. The presentation highlights that state enterprise reform in China underwent four development phases, namely; expanding SOEs autonomy (1978-1984), separating ownership and management (1985-1992), establishing the modern corporate system (1993-2002) and the state-owned asset management system (2003 to 2015). Phase I: Expansion of SOEs’ autonomy and reforming of the salary system (1978 - 1984) For a long period following the Chinese revolution, the SOEs were obliged to surrender most profits to the state. As a result, the SOEs were characterized by low salaries and low levels of comprehensive social security services such as lifetime employment, pension, housing, children’s education, as well as medical care. During Phase I, China piloted the reform of expanding SOEs autonomy and delegating profits management by implementing the system where SOEs retained profits. The system also promoted the economic responsibility system in industry. Through this way, SOEs obtained certain production autonomy, became independent entities, and thus, mobilized employees and broke through the traditional planned economy system.Phase II: Separation of ownership and management and implementing the contract system (1985-1992)During the second phase, SOEs adopted the contracted managerial responsibility system with a view to ensure the separation of capital owners and operators. However, since governments and enterprises could not be completely separated, SOEs were unable to assume sole responsibility for their own profits or losses. Consequently, the SOEs began to implement the transformation of internal management mechanisms, which were supported by reforms in the pricing system, circulation system and investment and financing system. In 1988, Shanghai pioneered in developing stock cooperative enterprises and set up 10 major state-owned asset investment companies as an attempt to implement government investment through market-based measures.Phase III: Establishing the modern corporate system (1993-2002)This phase was implemented in two parts. The first part was restructuring of small and medium-sized SOEs and the second part was assisting the SOEs get out of unprofitable status. In the early 1990s, small and medium-sized SOEs gradually started restructuring through option sales and overseas sales. Under this process, the government sold SOEs to private individuals, which however, led to corruption and the embezzlement of state-owned assets. In the late 1990s, SOEs implemented strategic restructuring, adjusted the state-owned economic layout and built the modern corporate system, which helped most SOEs in deficits get out of trouble. Meanwhile, SOEs also piloted supportive reform, optimizing asset structures, and promoted shareholding piloting and corporate system reform. As of the end of 1997, over 80% of the SOEs had adopted the corporate system in various forms and established a preliminary corporate governance structure.Phase IV: State-owned asset management system reform and mixed ownership reform (from 2003 to 2015) In 2003, the central government and local governments set up State Asset Management Commissions that served to integrate the rights of managing personnel issues and assets. The functions of the State Asset Management Commissions were defined according to the Interim Regulations on Supervising and Managing Assets of State-owned Enterprises. In the same year, the Third Plenary Session of the 16th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CCCPC) clearly presented the concept of mixed ownership so as to let market mechanisms play the leading role and build and perfect the modern property rights system. In 2005, China started to explore the flow of state-owned assets and gradually established a mechanism for the orderly flow of state-owned capital “cross industries, cross departments, cross regions and cross ownership”, focusing on competitive industries and fields, large-sized and super-sized mixed ownership enterprises. Further, in April 2005, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) launched the pilot reform of equity division, which was basically completed in late 2006. In 2008, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Enterprise State-owned Asset Law was issued, providing a legal basis for state-owned asset management.

4. China’s Experience in SOE Restructuring and Reform

- China experienced and passed many reforms, some of which achieved the desired objectives and some partially failed. Below are the restructuring and reform processes and experiences as reported by the NDRC (2015) on a work visit to Zimbabwe.1. Separating the functions of governments from those of enterprises, dissecting connections between large-sized SOEs and industrial ministries and setting up the State-owned Asset Management Commission. China abolished the administrative affiliation between governmental authorities and their economic entities and subordinate enterprises. Government separated the functions of state-owned assets from administrative functions, as well as the enterprise ownerships from management rights. China also set up the State-owned Supervision and Management Commission to enforce the state-owned asset management system, supervise the value preservation and increase of the state-owned assets in the enterprises, direct SOEs reform and restructuring, and promote the establishment of modern corporate system in SOEs.2. Bringing into full play the leading role of the state-owned economy in the national economy. While China further intensified the dominance of the state-owned economy in industries relating to national security, natural monopoly and key public products and services, SOEs gradually drew back from general competitive industries. Large-sized SOEs played a leading role in economic operation, growth and development, further improving the overall quality of state-owned assets. The top-level design for SOEs reform was implemented first, including the state-owned economy layout and restructuring and SOEs’ corporate governance structure improvement. It was stipulated that state-owned asset transactions should be implemented through public bidding. The investor approval list system was gradually established to create a suitable legal environment for SOEs reform. The approval was done in order to get the most credible investors to steer the SOEs ahead on performance.3. Adhering to the principle of advancing SOEs reform step by step while promoting SOEs reform; China has balanced well the relationship between reform, development and stability. From decentralization of power and transfer of profits to the establishment of modern corporate system; and the clarification of property rights to investors, China promoted SOEs reform actively, steadily and step by step, thus avoiding major social turbulences.4. Promoting the reform of monopolized industries and introducing competition mechanism to intensify governmental and social supervision. China actively promoted the reform of such monopolized industries as railway, expressway, electricity, telecom, water supply and gas supply. The reform adopted such measures as auctioning franchise rights to enhance the competitiveness and the efficiency of natural monopolized industries, and intensify the governmental and social supervision on these industries.5. Creating a favorable external environment for SOEs reform. China prepared adequate bad debt reserve to help SOEs in serious deficits to retreat from the market. At the same time, China established and improved the social security system to provide basic social security for SOEs employees who were laid-off. The burdens of SOEs were reduced by such measures as writing off bad debts and debt restructuring.

5. State Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) of the State Council of China

- The SASAC is a state supervisory authority whose main task is the modernization and restructuring of large SOEs. It has extensive authority to decide the operating systems of the SOEs and is therefore one of the most important decision makers in the management of SOEs (www.en.sasac.gov.cn/).

5.1. Main Functions and Responsibilities of SASAC

- Authorized by the State Council, in accordance with the Company Law of the People’s Republic of China and other administrative regulations, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council performs investors’ responsibilities. In addition SASAC also manages the state-owned assets of enterprises under the supervision of the Central Government (excluding financial enterprises), and enhances the management of the state-owned assets (www.en.sasac.gov.cn/).SASAC shoulders the responsibility of supervising the preservation and increment of the value of state-owned assets of the supervised enterprises through collecting statistics and auditing. It is also responsible for the management work of wages and remuneration of the supervised enterprises. SASAC formulates policies that regulate the income distribution of top executives and organizes implementation of the policies (www.en.sasac.gov.cn/). SASAC guides and pushes forward the reform and restructuring of state-owned enterprises while advancing the establishment of modern enterprise systems in SOEs. It improves corporate governance and propels the strategic adjustment of the layout and structure of the state economy (www.en.sasac.gov.cn/). SASAC appoints and removes the top executives of the supervised enterprises and evaluates their performances through legal procedures and either grants rewards or inflicts punishments based on their performances. It establishes corporate executive selection system in accordance with the requirements of the socialist market economy system and modern enterprise system and improves incentives and restraints system for corporate management. In accordance with related regulations, SASAC dispatches supervisory panels to the enterprises on behalf of the State Council and takes charge of daily management of the supervisory panels. SASAC is responsible for organizing the supervised enterprises to turn the state-owned capital gains over to the state. The commission participates in formulating management systems and methods of the state-owned capital operational budget. Furthermore, it is responsible for working out the state-owned capital operational budget and final accounts and their implementation in accordance with related regulations (www.en.sasac.gov.cn/).SASAC is responsible for urging the supervised enterprises to carry out the guiding principles, policies, related laws and regulations and standards for safety production. Additionally, it inspects the results in accordance with its responsibilities as the investor (www.en.sasac.gov.cn/).Apart from the fundamental management of the state-owned assets of enterprises, SASAC also works out draft laws and regulations on the management of the state-owned assets. It is worth noting that Chinese SOEs had their fair share of challenges and that further improvements are needed to succeed in the full establishment of a modern corporate system. Zimbabwe can, however, still take relevant notes. There is need for robust improvement in Zimbabwe’s SOEs corporate governance. Effective internal controls are yet to be fully established and more clarity is needed in the interactions that take place between supervisory authorities that oversee SOEs. SOEs still lack a system in human resource management that is geared towards managerial professionalism. The problem of direct government involvement in the management of SOEs and assets is still prevalent though at differing levels. A large number of operational matters that should be left to SOEs to decide are still subject to the approval of the government (Mid-term fiscal review, 2015). A mechanism for the regulation and evaluation of SOE assets still needs to be improved.

6. Chinese SOEs Contribution to GDP and Economic Development

- Chinese SOEs have over the years managed to improve corporate governance systems. They have also posted improved return on equity (ROE), profit-cost ratio and inventory turnover (Xiang Anbo, China Daily, 2015). The SASAC’s 2015 Report cited in Xinhua, (May 16 & 29) indicated that at the end of the first quarter of 2014, the 113 centrally administered SOEs posted an aggregate profit amounting to 576 billion RMB. The combined profits also increased 6.5% year-on-year to 742.84 billion RMB in the first 4 months of 2014 and the pace of growth was faster than in 2013. SOEs registered a 5.1% growth rate, much better than the 14.7% decline in the same period in 2013. The country’s SOEs revenue totaled 14.83 trillion RMB, reflecting a 5.5% year-on-year increase, while their operating costs stood at 14.29 trillion RMB, up 5.8%. The amount of taxes payable totaled 1.25 trillion RMB. By the end of April 2014, total assets of the enterprises had increased 10.9% year-on-year to 94.55 trillion RMB, with liabilities at 61.53 trillion RMB, up 11.1% from 2013. Some SOEs, in the transport sector recorded profits but enterprises in iron and steel and non-ferrous metal production continued making losses.The general increases in the performance of SOEs in China have made them a key player in the Chinese economy, contributing significantly to the GDP. In contrast, Zimbabwe’s SOEs have continued to perform dismally, putting a strain on the fiscus with government budgets set aside to salvage ailing SOEs. In a thriving management system, SOEs should otherwise post profits and declare dividends to the Government.

7. Overview of Zimbabwe’s SOEs’ Performances

- The reality on the ground shows that most SOEs are operating sub-optimally and have been posting perennial losses. For instance, Air Zimbabwe Holdings, NRZ, ZBC, CSC, PSMAS, GMB, City Councils and CAAZ, are struggling with heavy debts and very limited production capacity. This average-to-poor performance is attributed to the following challenges among others, poor state of infrastructure and equipment, lack of critical skills and expertise, non-compliance to good corporate governance practices, inadequate fresh capital injection from the shareholder, lack of access to lines of credit, low capacity utilization and market penetration, high operating costs especially the wage bills, poor debt recovery strategies, debt legacy and high inter-parastatal debt (Ministry of Finance: 2014 Fiscal Report).

7.1. Zimbabwe SOEs Legal Instruments

- The legal instruments that establish and govern SOEs are sub-divided into two categories. These are individual acts of Parliament which establish and govern statutory corporations referred to as “Parastatals” and the Companies Act which establishes corporatized entities referred to as “State Enterprises”. The country follows a decentralized ownership model for its SOEs. This ownership model is characterized by dispersed ownership of SOEs across line Ministries. The line Ministers have the responsibilities to exercise direct control over SOEs under their purview (Ministry of Finance: Medium Term Fiscal Policy Review, 2015).

8. Conceptual Framework

- The study utilizes the link between human resource management and corporate governance frameworks in order to explore complementarities in workstations to solve the Zimbabwe situation. This conceptual framework demonstrates the dilemmas and the richness of different interpretations of the theory of corporate governance in human resource management and most importantly, how the dilemmas can be resolved. The study tried to come up with a modest, logical and sustainable view accepted by all stakeholders. The framework exposes the crisis and potential conflicts likely to be encountered and how to solve them when corporate governance practices are implemented.Corporate governance has competing definitions and explanations and has stirred debate over the contesting subject matters highlighted in the study. Corporate governance encompasses a wide range of important aspects. Margaret Blair (1995:3) states that corporate governance comprises the whole set of legal, cultural and institutional arrangements that determine what publicly traded corporations can do, who controls them, how that control is exercised and how the risks and returns from the activities they undertake are allocated. Apreda (2008) provides a unifying view of governance as a distinctive field of learning and practice, identifying interlinked themes that arise from corporate, public and global governance. Apreda (2008) further identifies the core of governance in all three domains as a founding constitution, a system of rights and duties, mechanisms of accountability and transparency, monitoring and performance measures, stakeholder rights, good governance standards and independent gatekeepers.The dilemma in corporate governance as Clarke, (2007) noted, is that there are competing corporate governance systems in different economies. For instance, the market-based Anglo-American system, the European and Asia Pacific relationship based system, and the ‘African way’ of doing things are all not the same in their nature and context. This also calls for flexibility in crafting governance arrangements that are responsive to unique business contexts so that corporations can respond to incessant changes in technologies, optimal firm organization, competition and vertical networking patterns (Clarke T, 2007). Corporate boards in Zimbabwe, however, seem to have abused this flexibility by turning a blind eye to the firm’s survival and milking the enterprises to fulfill their personal remuneration demands. The willful blindness to firm continuity was witnessed when boards and top executives continued with their management benefits payments amid poor organizational performance and non-pro-active counter measures to stop the firms from further sinking. This was compounded by government’s late response despite the fact that cabinet ministers were aware of the rot (Ministry of Finance: Auditor General Report, 2015). This shows that there is need for a critical review of governance practices in Zimbabwe, which would address various issues as they occur, especially the accountability issue, where ministers are not responsive to the maladministration of organizations they are supposed to superintend over. Zimbabwe should also come up with a system of capital compensation, where executives convicted of embezzlement of funds, must pay back the amount rather than being jailed for a term as the state would benefit nothing from the incarceration.

8.1. Ownership and Control

- Ownership and control affects corporate governance in respect of how to construct rules and incentives to align the behavior of managers with the interests of owners. It needs to be supplemented with other models of corporate control such as stewardship, stakeholders, and political models applying not only financial analysis but a cultural and power analysis, among other perspectives (Tricker R, 2008). In Zimbabwe, SOEs managers and boards somewhat failed to uphold the shareholder’s interests as the shareholder (government) could not enforce rules and regulations especially where the rot involved ministers, senior government officials, political leaders and board members. A sense of ownership as well as stewardship should be inculcated in the heads of SOEs and stakeholders including managers and employees. There is need to create a cadre of highly trained and efficient managers and employees who have their country at heart rather than those who prioritize personal gain ahead of national interest.

8.2. Boards and Directors

- Contest for Control: Boards and DirectorsThe board of directors often does not live up to expectations. Boards are usually caught asleep and fail to demonstrate the strategic alertness expected of them (Clarke T, 2007). One of the greatest sources of tension is between what the board of directors believes is their legitimate claim to exercise ultimate control of the company and management’s determination to retain what they define as the necessary level of operational control of the business (Demb A & Neubauer F.F, 1992). This is reflective of the turf wars in Zimbabwe between the board, minister and the firm management where all struggle to take full control of the firm, one bypassing the other. The situation also gave rise to agency conflict (external and internal forces) thereby affecting the effectiveness of the organization. Some scholars believed that the most dominant conflict flows from the fact that though the board has formal power over management, in practice management dominates the board and unfortunately the political influence would come into play. Mizruchi (2008), however, asserts a different view, insisting that the board remains the ultimate centre of control. The degree of control varies, depending on circumstances, as boards tend to become more involved in times of crisis but management sometimes feels that the board overlaps. Be that as it may, the board possesses ‘bottom line control’ in setting a framework within which management must operate. Many a time, however, management quickly develops mechanisms to protect themselves, thereby affecting the strategic effectiveness of the firm (Hoskisson 2008). This situation is currently prevalent in Zimbabwe’s state enterprises and was precipitated by divergent stakeholders’ interests, arising from divergent backgrounds. The board of directors and the minister for instance are usually politically inclined and the management who operate business on a professional basis has a different approach to business. A clash therefore would arise.The role of the board is not to formulate strategy but to ensure that the company is focusing on what it is supposed to do by giving guidance and direction. The major challenge here is to ascertain how the board can monitor such issues without interfering with management decisions. The board is to question management commitment to achieving set goals and realizing the organization’s vision. This spells the start of the conflict. However, Weir et, al (2008) calls for more flexibility in the development of company specific governance structures appropriate for companies at different stages in their life cycle, and operating in different markets.In Zimbabwe, line ministries are mandated to run parastatals. The line minister appoints the board of directors upon approval and consultation with the State President. The minister has the mandate to supervise the board members. The minister can hire and fire the board after consultations with the President. However, the controlling ministry does not bear any residual risks over the control and use of SOEs assets. This implies that losses and risks are simply passed to the public at large, contrary to public listed companies where shareholders are the residual risk bearers. Furthermore, the minister reports to cabinet on the company situation. The minister can also be summoned by parliament to answer anything to do with the companies directly under his or her portfolio. The parliament acts on behalf of the public but has no decision-making power. Parliament also acts as an inspectorate body or police without arresting powers. The role of parliament is also to enact relevant policies of state enterprises management and operations. It should be noted that the President’s involvement is that he is the chief executive of government who is responsible for the appointment of ministers and administration of the Acts. Vision of reform and operations are reported to the President. The chief secretary through the Office of the President and Cabinet (OPC) is to oversee the implementation of the discussed operations and also update the president. However, the board appoints the chief executive and the chief executive appoints his management team and is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the business (GoZ Gazette, 2015). The above is the complication of the reportage system, supervision, overseeing and management of SOEs. If the OPC oversees the implementation of the policies and reports to the State President and the minister can also report to the State President directly, it then creates a situation where the concerned parties compete to report to the same person for the same work. The situation draws a civil servant against a politician where the two people have different command power, influence and voice in government decisions. Such clashes and competing voices of authority may delay decision-making and are detrimental to the process of realizing beneficial change. The two stakeholders should remain professional in their approach to achieve better results.Furthermore, the minister could be seen abusing political powers to bulldoze the day-to-day business operations that are in conflict with the ethics and values of corporate governance. The board members may tend to fear to voice their concerns to the minister as they serve at the minister’s pleasure. As a result the company would be run on parallel strategic visions of the board and management. This creates turf wars and incoherencies within the firms. It also breeds an opportunity or culture of political predation (Ncube F, 2014). This is evidenced by the current situation in the country where line ministers technically took control over state enterprises disregarding the board. This resulted in boards or executives taking a sit-back and watching over the minister do the business running of the SOE. This is also compounded by the fact that, in some cases, boards are not in existence or do not constitute a quorum or the chief executive is serving in an acting capacity for an extended period and cannot make certain key decisions. For instance, the ZBC, NRZ, ZUPCO and Air Zimbabwe are operating without a full board and or without a substantive chief executive officer.The problem of a political minister appointing a board is that, political and personal interests in identifying the board members, rather than the professional attributes of the would-be board members can influence the minister’s choice. Evidence on the ground was that, in some boards, members are selected on the basis of tribe, region of origin, political factional lines and friendship rather than competence and qualification. This however, impacts negatively on the competence of management of the enterprises.The absence of necessary board committees within SOEs is a cause for concern as some issues are too technical to be handled by the board members, who in most cases were appointed without the right skills. As a result there is great potential to see serious omissions and commissions in the management of the SOEs. Therefore, there should be a clear separation of powers and responsibilities among stakeholders. Clear communications lines should also be followed and adhered to. Recruitment and placement of competent personnel should be implemented. A sense of belonging (cadre or national interest) should be educated to all stakeholders.

8.3. Executive Compensation: Central Concerns

- Managers or executives must be well paid; the reason being that the work they do involves high skilled decisions, which can involve billions of money. But this should be subject to transparency and also that they must be treated as workers not as super humans; they must be guided accordingly (www.chinadaily.com.cn). However, the approach of high SOE manager payment is widely criticized in Zimbabwean circles due to varying reasons, as Clarke (2008) indicates that accepting the complex demands of the executive role in large corporations, does not necessarily justify the extra-ordinarily large reward packages demanded by some CEOs. It brings into question whose interests CEOs are serving when the organization is failing while executives are earning huge salaries. The rationale can be questioned as unrestrained CEO pay or compensation does not justify one’s efforts. Matsumura and Shin (2008), examined the intended and unintended consequences of widely proposed executive compensation reforms. They concluded that whatever remedies such proposals might offer, given the intrinsic limitations of regulatory actions intended to discipline executive pay, what is required is a stronger ethical framework which redefines corporate objectives and takes account of the interests of a broader group of stakeholders. Conyon (2008) highlighted that CEO pay must be correlated to firm size, profitability, cash flow, and growth perspectives, labor market and compensation practices, a practice which may not be evident in the Zimbabwean context at present where CEOs’ remuneration packages are pegged with little or no regard to company performance or output. This still has created problems where SOEs have failed to productively perform to justify the CEO salary levels. Ideally, CEOs should be paid according to the respective firms’ ability. It is hard to escape the conclusion that executive compensation is part of the problem rather than a solution to governance dilemmas Conyon M.J. (2008). This framework brought distortions on how Zimbabwe CEOs in state enterprises were awarded huge salaries (see appendix) which were not commensurate to company production and performance, resulting in company bankruptcy. The ZBC and Air Zimbabwe are some examples, which continued to pay executives more than what the company could produce and afford. It therefore resulted in firms’ failure to meet the day-to-day needs. A code of conduct should be crafted to take into account such distortions so that the payment system is in tandem with the firm’s ability to pay. Reasonable ground should have been reached to come up with such a pay structure.

8.4. CEO Power

- The CEO exercises formal authority as well as informal power (Pfeiffer, 1992). CEOs create internal and external dynamics to retain power. In some cultures, CEOs do not have evident powers but in some have exclusive powers and are heads above others. Adams (2008) discovered that firm performance becomes more variable as decision-making power becomes more concentrated in the hands of the CEO, compared to firms in which decisions are a product of executive consensus.A situation obtaining in Zimbabwe state enterprises reflected that CEOs have not much absolute powers as they are usually guided by the Cabinet authority or the parliament. Any major decision that the CEO would want to implement should pass through Cabinet or parliament for approval. This bureaucratic reportage system had stifled corporate growth as great ideas ended up being abandoned or overtaken by events.On the other hand, line ministers often wielded too much power on the day to day running of the company. Line ministers have gone as far as influencing internal promotions and deployments of personnel. This situation would render CEOs powerless in the administration of the company. This is because CEOs are usually appointed on the basis of political background or other factors that are not on professional or competency based. The appointments of the GMB, ZUPCO, ZBC, NRZ, ZINARA and Hwange Colliery CEOs are testimony of unqualified and incompetent heads, all appointed on political background. This had contributed to the poor performances exhibited by these organizations.However, the selection and powers of state enterprises CEOs remains subject of debate in Zimbabwe. The researchers however propose that CEOs should retain their absolute or executive powers. The appointments of CEOs should also remain professional and transparent. The criteria and qualification should be spelt out clearly. They should therefore be accessed by a competent board of directors.

8.5. Role of Chairperson

- In the US, the Chair is usually the CEO. However, in UK and Europe, the role is separated as it is viewed as concentration of power and most prone to abuse. It is argued that the division of responsibilities permits a balance of power and authority, ensuring no individual has unfetted decision-making power (Cadbury, 2008b). The division of powers is normally that the Chairman is responsible for the board and all of its duties and the CEO is responsible for the running of the company. However, this clear delineation of roles may often be less clear in practice and depends on the relationship of the two individuals and their relationship with the rest of the board (Coles and Hesterly, 2008). The Zimbabwe situation once again is mixed. At one time the chair is not different to the CEO. For example, the chair and CEO of Zimbabwe Minerals Development Corporation, Air Zimbabwe and NRZ were once doubling the duties of chair and CEO until the parliament and Auditor-general questioned the status quo. The researchers therefore suggest that the Chairman should be independent in order to execute decisions with undue influence from the owners, management or political party.

9. Methodology

- This section focuses on the research design or plan, sampling methods, data collection procedures as well as data analysis, interpretation and presentation. This research used qualitative techniques to analyze how different human resource management styles and practices can be implemented to enhance the effectiveness of state-owned enterprises in Zimbabwe. The study utilised non-probability purposive\sampling procedures that apart from being convenient to the study were targeted at SOEs that are of a strategic importance to the Zimbabwean economy. The study also used both primary and secondary data. Numerous sources of information such as periodic reports from several governmental offices such as the Auditor-General, Treasury Department, Anti-Corruption Commission, executive speeches by key government personnel, parliament debates, seminars, business confederations and media reports were utilised.The study also collected information from various texts by several researchers on governance across the world. Comparisons between the Zimbabwean and Chinese scenarios were made for purposes of critical analysis. Secondary data helped to compare the current arguments with previous arguments by other scholars. Some case studies were read and analyzed as part of secondary information to give authors the basis for arguments. Much of the information about the selected state enterprises that are of strategic importance was also obtained through key informants such as CEOs, employees from state enterprises, economic analysts and line ministry personnel by means of interviews and interactions. These sources highlighted corporate governance challenges affecting state enterprises in Zimbabwe. The study was further motivated by the Chinese SOEs’ success stories as outlined by the NDRC, SASAC, academic reports and the Chinese media.

10. Human Resources Management Challenges and Counter Solutions in Zimbabwe’s SOEs Learning from the Chinese Experience

10.1. Obsolete Skills and Training

- Established at the country’s independence with some personnel having been there well before 1980, Zimbabwe’s state enterprises have largely remained the same despite the changing operating environment. It should be noted that major changes brought about by technological revolutions over the past decades have necessitated new skills in the work places. Personnel in state enterprises have been slow in adapting as most parastatals generally exhibit a deficiency of the required skills to work in modern organisations; thus, parastatals have not been proactive enough to respond to the changing environment (GoZ, 2015). Generally, state enterprises in Zimbabwe exhibited a deficiency in modern skills because personnel have not moved with the modern human resources development trends. Though refresher courses continue to exist but the training equipment and methods remain archaic and fail to adopt the efficient and effective way of doing business.Technological changes from mechanized industries to highly automated ones have also seen most of the seemingly experienced personnel in parastatals being as obsolete as the equipment they use. This has led to a general problem of overstaffing and low employee productivity leading to high cost of doing business and, as a result, making these entities perennial loss makers. This is evident in companies such as NRZ, ZBC, GMB and Air Zimbabwe where the companies are suffering from high wage bills brought about by overstaffing as a result of redundancy. The problem has also been caused by low or no budgets for training or the lack of planning by management for staff development. The fear by government to lay-off excess or redundant staff is that, for the sake of political expediency, it is not a recommended option due to the bad state of the economy in general. The fear of mass uprising cannot be over-emphasized.A leaf can be taken from China where according to SASAC & Carl Duisberg (2015), the Chinese SOEs have been engaging Carl Duisberg Centre, (a Germany training consultancy) in executing annual qualification programs for executives of Chinese SOEs since 2002. The programs dealt with different management topics and included visits of German companies in order to support the initiation of business relations between German and Chinese companies. The aim was to strengthen the management expertise in SOEs. Seminars and company visits allowed the participants to gain insight in best management practices.

10.2. Poor Work Ethic

- The era of monopolies and government subsidies to parastatals brought about a generally poor work culture, as observed through inefficiencies and the general poor work ethic by personnel. Human resources in parastatals, generally have a lethargic approach to work. As noted by Zhou (2012), nepotism has been one of the contributing factors to poor SOEs performance. Poor customer service and failure to meet deadlines and set targets are the norms in most state enterprises. Most SOEs have been characterized by poor management cultures that have led to the downfall of the once highly productive entities. A number of SOEs have discarded a culture of good stewardship, which resulted in carelessness in decision-making and loss of internal control measures. This was evident at ZBC, CAAZ, PSMAS and NRZ where executives enjoyed huge packages not commensurate with production. Benefits such as huge basic salaries, housing allowance, domestic workers’ salaries, entertainment allowance, and vacation allowance were highly inflated, as noted by Professor Jonathan Moyo, the former Minister of Information in the Sunday Mail article of February 2014. (See appendix). This led to employee frustrations as they were not being paid or they would be paid half salaries. However, absenteeism and absenteeism-at-work reached alarming levels, resulting in loss of production. This exhibited the lack of leadership and managerial carelessness in the state enterprises in question.Looking at the Chinese experience, the authorities have worked well to counter issues of bad working culture, employee carelessness, non-performance of duty and extravagance. The following were counter measures to curb such misdemeanors. The Chinese central government developed a code of behavior that bans and restricts all public officials going to lavish banquets and luxury clubs. Officials were also ordered to minimize meetings, cut spending and follow strict housing and vehicle standards. This was done to reduce bureaucracy and other undesirable work practices.The China Daily of January 01, 2015, reported that the government had netted over 100 000 officials for not heeding the frugality campaign. It further reported that officials caught violating the policies were reprimanded and some were punished by both CPC-CCDI. Such violation practices included disobeying workplace rules, overseas travel and personal entertainment financed by public funds; negligence and lazy work practices; excessive spending on receptions and vehicles, extravagant weddings and funerals and sending or accepting gifts. Moreover, a regulation was effected to punish official incompetence, where the CPC issued a new regulation aimed at demoting or sacking poorly performing officials. The regulations applied to all government officials and SOEs employees (China Daily, 26.06.2015). As reported by Xinhua News (2015.01.08), the CPC had even expelled its members who were caught by the blitz. However, Party officials had also expressed fear that “too much punishment of senior officials could harm the stability and development” of the country. This practice led to employees and officials being accountable and disciplined, a point that is lacking in Zimbabwe’s Government and its SOEs.

10.3. High Human Resource Turnover

- In the pre-Economic Structural Adjustment Program (ESAP) era in Zimbabwe, parastatals used to be employers of choice. The trend has, however, generally reversed today. The generally poor working environments exacerbated by tight liquidity positions have pushed most parastatals into insolvency and some are just limping through courtesy of government bailouts. This situation has caused some of them to neglect employee welfare. In the face of these challenges, Zimbabwe’s state enterprises witnessed the exodus of critical staff.The perceived poor working environment compromised by political influence has made it difficult for parastatals to attract and retain talent at all levels. Furthermore, perceived insecurity due to vulnerabilities of being sacked at the instigation of an incoming Minister limits the scope of potential applicants to take up the job. Moreover, there has been high staff turnover due to other factors such as lack of employee development and promotion. Many a time there is widespread staff frustration when management appointments are given to outsiders, thereby limiting the prospects of promotion from within. The appointment of ex-military and/or serving military personnel in boards and executive posts in state enterprises is commonplace (Ncube F, 2014). What frustrates most is the fact that there is no evidence of special skills in such appointments. Some of the appointees have glaringly failed to deliver on their assigned mandates. It is therefore imperative that such key appointments be guided by competence and skills criterion. In addition, the generally poor working conditions characterised by poor remunerations and proper employee retention policies for the middle and low level workers have, over time, prompted most of the experienced and skilled manpower to seek for greener pastures in neighbouring countries such as South Africa, Botswana and Namibia and as far afield as Australia, New Zealand, UK, Canada and the US. This has left a skills void within the SOEs. Meanwhile, budgetary constraints have led to less recruitment and limited staff development through training over the years, a factor that has undermined SOEs’ respective abilities to fill up the skills gap. Consequently, some SOEs have gone for years without substantive key personnel such as chief executives or board members. Parastatals such as ZBC, Cold Storage Company (CSC), GMB, NRZ, ZUPCO, PSMAS, ARDA and Air Zimbabwe, have all gone for extended periods without substantive CEOs and Board members. This invariably compromised the smooth running of business operations in these entities. It is critical that, whenever there is a vacancy, appointments of substantive executives should be done at the earliest opportunity possible, rather than delaying until such time the SOE or parastatal is in distress.It can also be suggested that refresher courses and exchange programmes targeted at employee skills development be given as a solution to close the skills gap in these state enterprises. Such programs would enable the employees to learn new models/trends of management and/or production and share experiences with others. Companies can also develop incentives that are attractive to employee development and retention.A leaf can be taken from the Chinese situation where employees are highly motivated through monetary and non-monetary reward systems. For example, employees are given suitable accommodation, children are sent to good schools, and health and medical insurances among other social nets, are catered for. On promotion, employees are largely appointed based on competence where independent panels, individuals and the Party are involved in the recruitment, selection and placement of personnel. Doing business right and right management of employees is the basis of success in the Chinese business-operating environment. It is, however, noteworthy that bias cannot be ruled out and mistakes could happen in appointments. There is still a chance to improve the political cadre promotion system through reforms to enhance objectivity and fairness.

10.4. Lack of Performance Based Reward Practices

- The reward systems in Zimbabwe’s SOEs and parastatals seem not to recognise performance. The current low productivity levels characterizing the SOEs and parastatals clearly points to a concentration of non-performers in those enterprises. Most of these enterprises have great potential if work performance is enhanced. In modern enterprises, the Human Resources Committee of the Board, in line with the performance contracts, usually monitors CEOs and top management. Such systems should be applied to enhance performance in SOEs in Zimbabwe. The Best Employers Study by Ao Hewitt (2013) concluded that companies characterized as having high performance cultures tend to reward their outstanding employees with incentives that are more closely linked to their performance. This linkage, in turn, drives employees to achieve corporate goals and visions. In this regard, pay structures in SOEs should be directly linked to performance.A note should be taken from Ao Hewitt (2013) who observed that, employees only care about the figures on their pay cheque and lack overall awareness of their benefits. To confront this dilemma, organizations should be more concerned about increasing their employees’ awareness of long-term incentives and other benefits. Organizations should adopt effective communication approaches to communicate such benefits to employees, thereby enhancing employee awareness, understanding and appreciation of the total reward package.Lessons can be drawn from the practices of the Chinese Government where personnel remuneration is based on a pay-for-performance system practice. The thrust of such a system is to create a high performance and foster corporate culture within staff members. This is one of the reasons why Chinese SOEs represent one of the most productive forces in business (Annual Human Capital Intelligence Report, (2013), January 8, 2014).

10.5. High Turnover of Parastatals Leadership

- Some key parastatals in Zimbabwe generally experience a high turnover of leaders. This has generally caused a great deal of instability and lack of strategic focus in these entities. This high labour turnover amongst key people has been due to the fact that the ministers are responsible to appoint boards and CEOs, and their terms of office have generally followed the cycle of politicians. Any new minister tends to come in and appoint his own board, which in turn relieves the existing top leadership from their positions to bring in their own preferred candidates. This has been a perennial cycle, causing instability, lack of strategic focus and continuity in parastatals. Related to that, hierarchical challenges and frustrations flowing from unclear boundaries of authority and responsibilities amongst the stakeholders- ministry, the board and the executive- have and continue to fuel high leadership turnover in SOEs in Zimbabwe. For instance, one day the board would be mandated to deal with specific issues and the next day, the ministry would be undertaking the same issues or conflicting issues and many a time, the CEO ends up receiving conflicting instructions thereby creating confusion. Usually, the political instruction from the line ministry prevails in such a situation and, when that happens, the primary goals and/objectives of the enterprise in question suffer because decisions would have been made on political basis, rather than commercial considerations. For example, decisions on use of money for purposes other than goals of the organization. Apart from undermining the efficiency of the enterprise in question, such overstepping of roles creates turf wars among the stakeholders. Ideally, line ministries should not interfere on matters that should be dealt with by management and the board to allow for effective organizational performance.In this regard, there is need for the setting up of proper and clear structures that would ensure clear lines of responsibilities, proper accountability, clear communication procedures and any political intervention that could be necessary.Lessons can be learnt from the Chinese experience where the CPC recognized the international norm of a large company having an independent board to which their senior managers are accountable (Edwards Susan (2013) and CKGSB Knowledge, August 21, 2013). Furthermore, a growing number of Chinese SOEs have adopted modern corporate structures with boards of directors responsible to shareholders and supervising the management of business operations. In addition, SOEs’ corporate governance has also been strengthened through shareholding reforms, with a growing number of SOEs being publicly listed. These reforms have moved SOEs away from being direct affiliates to the central planning system, with the government no longer involved in most SOEs’ day-to-day operations (www.xinhuanet.com).In terms of reporting structures, Chinese SOEs are no longer attached to, or directly run by state ministries. SOEs report to the state owners who are various government agencies at the central, provincial or local level (www.xinhuanet.com). As a result, SOEs are subject to greater market discipline, enjoy more autonomy and are more accountable for their performance, although the SOEs’ achievements still fall short of making the entities ‘modern enterprises’.

10.6. Overstaying and Intra-Swapping of Parastatal Leadership

- The other extreme in as far as leadership in parastatals is concerned has been the overstaying of some CEOs and Boards at the organizations. This has caused a general stagnation and deterioration of these entities due to lack of leadership renewal. Some of the historically best performing CEOs have deteriorated to be amongst the worst performers as leadership and strategic thinking fatigue set in. NetOne, ZISCO Steel and NRZ are some classic examples where board members had overstayed in breach of corporate governance procedures. Mr. Mike Ndudzo had been head of Industrial Development Corporation of Zimbabwe (IDCZ), a state enterprise. Mr. Karikoga Kaseke had also been leading the Zimbabwe Tourism Authority for the past 20 years. Such practice reflects a lack of enforcement of rules and regulations on the part of government and the line ministries. In many cases, this has been compounded by the cyclical rotation of non-performing board members with trails of corrupt activities. What also boggles the mind is that wherever such board members were deployed as part of the rotation, they would leave the organization in a sorry state.There was also a trend in Zimbabwe where some board members would sit in multiple boards that exceed the maximum allowable according to the stipulations by the corporate governance regulations. This invariably distracts the board members in question from performing at their level best in any of the positions as they are sometimes found sitting in boards of competing organizations, a factor which compromises the integrity of their advisory role as board members. A leaf can be taken from Chinese Government where all the contract specifics are thoroughly adhered. The strict enforcement of rules and regulations has been the government’s strength in the operations of its duties. Appointments are done, as they are due and demanded, something that is lacking in Zimbabwean systems. As can be learnt from China, promotion is based on how individuals will have acquitted themselves in managing office. If one presides over a failing parastatal, one cannot expect to rise politically. There seem to be no reward for failure in China.

10.7. Lack of Leadership Capacity to Steer Parastatals

- It goes without saying that given the political cycles that leadership appointments follow, there is always a challenge in managing the quality of the leadership personnel being appointed. Evidence on the ground is that most of the leadership personnel appointed to run parastatals do not have the right skills and capacity to run them. Most parastatals have therefore struggled to move forward in the absence of competent leadership. In Zimbabwe, most parastatals have failed to groom and coach leaders from within because of the leader appointment process that generally follows political circles. This has given rise to what can generally be termed mediocre leadership within the SOEs, hence the uncompetitive position that most of them find themselves in. Politically appointed executives have shown trails of mediocrity because their stay is on the basis of political connections rather than competence. Many a time such executives have shown arrogance in their behaviour and decision-making, exhibiting lack of discipline. Worse still, some of such political appointees have been promoted and went on to become government ministers. Meanwhile, it is on record that the Chinese government has jailed, dismissed and made some executives to compensate the losses of the enterprises they were superintending, if it was deemed that the losses were as a result of sheer dereliction of duty. This way the system has managed to move away from leadership structures composed of only politically trustworthy individuals to economically capable personnel (www.scmp.com).

10.8. Corruption

- The continued mismanagement and corrupt activities in Zimbabwe SOEs such as PSMAS, is a sign of a deficiency in corporate governance, agency management and misconduct. If human resource management systems were sound and enforced, such problems would not have made headlines. Substantial corruption-inspired losses have crippled many parastatals as managers abdicated their role of being custodians of shareholder assets to being plunderers. A number of financially troubled SOEs such as ZBC, PSMAS, NRZ, Air Zimbabwe, GMB, ZUPCO, ARDA and Harare City Council, are in such state of affairs due to corrupt activities (www.herald.co.zw, 2015.05.05). Corrupt activities range from payment of salaries and allowances which are not commensurate with the performance of the enterprise, flouting of tender procedures for personal benefits, employment of ghost workers, deliberate over-staffing where relatives and friends are employed resulting in the duplication of duties. In many cases, executives had failed to put in place internal risk control measures. The insurance case of Air Zimbabwe where the airline deliberately paid for two insurance policies with two different companies for the same fleet and risk was one such testimony of a deliberate omission by executives. Corruption and abuse in Zimbabwe SOEs has been increasing without much effort to curb it. This is unlike in China where the anti-graft body, the Communist Party of China Central Commission Disciplinary Inspection (CPC-CCDI), upgraded and reinforced the fight against corrupt activities. Special and systematic regular inspections have been carried out in state enterprises and institutions. This has effectively exposed corruption suspects (China Daily/Xinhua, 2015.01.08). The same publication further reported that more than 70 executives had been investigated. Some were found guilty, some acquitted and others issued with ‘serious warnings”. The Chinese anti-corruption body also warned “officials at all levels that those who turn a blind eye to the corruption of others will be held accountable”. Such officials may face demotion for failure to report on colleagues even if it involved top Party chiefs. Top Party chiefs had fallen victims of the blitz (Zhang Yi, China Daily, 2015-09-08). The above signifies the degree of importance the Chinese government places on fighting corporate corruption

11. Conclusions and Recommendations

- While country circumstances differ, Zimbabwe can draw lessons from China’s SOEs reforms. China has developed a strong SOEs corporate strategy based on a number of factors such as a strong work ethic, discipline, enforcement and monitoring of policies, crackdown on corrupt activities, accountability, following up on proper procedures in executing work tasks, non-tolerance on laziness, accomplishing tasks on time, performance related incentives and strong supervision systems.Among the many factors, one of the most important factors that enhanced Chinese SOE performance was great discipline and hard work. The determination to achieve set targets makes the Chinese focused. Zimbabwe can draw lessons from that. The Zimbabwean government must also continue with efforts to improve efficiency and effectiveness of SOEs by enforcing compliance to good corporate governance and improving performance management systems (performance contracts). What is needed for Zimbabwe is to appoint competent managers to manage SOEs and never reward them at the slightest signs of failure. This will cultivate a culture of hard work and great discipline.Based on the Chinese cycle, the authors recommend that:a. Zimbabwe should separate SOEs from supervision by line Ministries. In this regard, the establishment of a Government commission to administer and supervise SOEs along the lines of China’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), clearly spelling out the role of commissions that are responsible for managing state assets (SOEs), is important. b. Institutionalized management should be strengthened. Formulation of adaptable state-owned asset operational budgets, assessment of the qualifications of SOEs board members, directors and supervisors, SOEs manager remuneration management systems and intensification of SOEs manager-remuneration assessments are all but critical. c. Worthy of note is that the establishment of a single body to manage state assets is overdue in Zimbabwe. d. The Government of Zimbabwe may further intensify supervision of state-owned assets to prevent asset losses. It is recommended that the government should focus on the consolidation of the basis, standardization of the systems, innovation of the mechanisms and integration of the resources. In order to speed up the establishment of state-owned asset supervision system the following measures should be taken into consideration; intensifying the formulation of supervision laws and regulations to build a legal firewall that prevents state-owned asset losses, establishing and perfecting the state-owned capital budgeting systems to promote overall budget management and building the framework of state-owned asset budget management systems.e. It is important to establish and implement improvements in corporate governance structures within SOEs. In this regard, it is recommended that the rights and liability boundaries among authority organs, decision-making organs and supervision organs of SOEs be clearly defined so as to build a complete responsibility system that eliminates the room for infringement. When the rights and liability boundaries are clearly defined, the responsibilities also become clear and unambiguous. It then becomes possible for the representatives of state-owned property rights to make decisions for the benefit of the investors, and the managers can now execute the decisions made by the board of directors and the board supervisors can supervise the board of directors and the managers so that each of them can perform their functions and assume their responsibilities as would be expected of them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Sincere acknowledgments go to Memory, Anotida and Lee Jean Muzapu. Special thanks are also due to Ambassador Paul Chikawa, Mavis Sibanda, Charles Chimimba, Glenda Mandizvidza, Meshack Kitchen, Vengai Shoko, Barbara Mukahanana, Maxwell Goodho, Lovemore Matemera, Sifikile Donga-Sibanda and Memory Mashavave for their valuable contributions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML