-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2016; 6(3): 64-75

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20160603.02

Toward We: A Conceptual Model to Reach Collaboration in Policy Making

Rahmatollah Gholipour, Mojtaba Amiri, Khadijeh Rouzbehani

Dept of public administration, University of Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Khadijeh Rouzbehani, Dept of public administration, University of Tehran, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The environmental contexts in which organizations operate are becoming increasingly complex and turbulent. Complexity principally stems from the nature of the problems organizations face: the issues that constitute these problems are extensive and interconnected, and usually associated with high levels of uncertainty. Turbulence, on the other hand, arises when the organizations that share it become increasingly interdependent. The complexity and turbulence of the environment thus makes it difficult for organizations to act unilaterally to structure and solve the problems they face. This issue is of great importance nowadays specially in public sector where problems are to be structured and the policies are to be implemented in collaboration. This research is going to present a conceptual model in problem structuring phase in order to maximize collaboration. Since the health sector and health policies are of utmost importance, health experts, policy makers and practitioners in this sector have been interviewed .The results prove that power, dialogue and shared meaning play the vital role among which dialogue has the key importance to reach collaboration among actors and stakeholders.

Keywords: Problem structuring methods, Collaboration, Domains, Dialogue, Shared meaning, Power, Multi-Organizational teams

Cite this paper: Rahmatollah Gholipour, Mojtaba Amiri, Khadijeh Rouzbehani, Toward We: A Conceptual Model to Reach Collaboration in Policy Making, Management, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 64-75. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20160603.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The environmental contexts in which organizations operate are becoming increasingly complex and turbulent. Complexity principally stems from the nature of the problems organizations face: the issues that constitute these problems are extensive and interconnected, and usually associated with high levels of uncertainty. Turbulence, on the other hand, arises when the organizations that share it become increasingly interdependent. This interdependency is also associated with high levels of uncertainty, as organizations, acting independently and in diverse directions, create unanticipated consequences for themselves and others (Emery & Trist, 1972). The complexity and turbulence of the environment thus makes it difficult for organizations to act unilaterally to solve the problems they face (Gholipour & Rouzbehani, 2016).Several forms of inter-organizational relations (IORs) have emerged in recent decades as a response by organizations to the complexity and turbulence of their environments. Typically, the particular form an IOR adopts will depend on whether organizations wish to jointly develop a shared vision, resolve a conflict or gain ‘collaborative advantage’ (Gray, 1989; Huxham, 1996).IORs can range from strategic alliances and joint ventures between business organizations (e.g. Das, Sen, & Sengupta, 1998; Dickson & Weaver, 1997; Saxton, 1997) to less institutionalized collaborations among a wide variety of stakeholders concerned about issues of common interest (e.g. Carpenter & Kennedy, 1988; Gray, 1989; Huxham, 1996). Whatever the specific form of IOR adopted, its general purpose is to enable organizations to manage their future collectively.Different theoretical perspectives have been used to conceptualize inter-organizational relations including transaction cost economics, exchange theory, organizational learning and institutional theory (for recent reviews, see Barringer & Harrison, 2000; Gray, 2000). In this study, the authors will draw principally on the body of literature on inter organizational domains in order to propose a conceptual model to increase collaboration among actors in policy making.A domain is a social system which comprises a set of actors with a common interest in a problem area which cannot be resolved unilaterally by any single actor (Gray, 1989; McCann, 1983; Milward, 1982; Trist, 1983). An inter-organizational domain is not an objectively given entity but one that is socially constructed (Berger & Luckmann, 1966) by the actors who constitute the domain. Initially, the boundaries and identity of the domain are usually unclear, shifting or in dispute (Gray & Hay, 1986). A key activity of this process of socially constructing the domain is ‘joint appreciation’ (Trist, 1983; Vickers, 1965), which involves actors making judgments of fact and value about the domain. These include judgments about what the domain is, and what it will or might be on various hypotheses. Through joint appreciation, the problems and actors that constitute the domain are clarified and stakeholders identified, and an identity and mutually agreed upon boundaries (Dunn, 2012) for the domain are created. New appreciations are made as new problems arise within the domain, which may lead to new boundaries and a new set of stakeholders (Gray, 1989; Trist, 1983).Once the identity and boundaries for the domain are created, stakeholders can be expected to reach agreements to regulate their future activities. These may take the form of policy recommendations to the stakeholders’ constituencies, or ad-hoc arrangements that need not involve formalized agreements concerning stakeholders’ future interactions for which enforced provisions are specified. It is possible, however, for stakeholders to create formal, long-term structural arrangements as mechanisms to support and sustain those activities which contribute to their ‘joint appreciation’ (Gray, 1989; McCann, 1983; Trist, 1983). These formal arrangements may include rules governing future interactions among stakeholders and the design of stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities.An inter-organizational domain thus can evolve from being an ‘under-organized system’ where actors act independently, if at all, with respect to the problems that constitutes the domain (Brown, 1980), to what can be considered a temporary ‘negotiated order’ (Altheide, 1988; Gray, 1989; Heimer, 1985; Nathan & Mitroff, 1991; O'Toole & O'Toole, 1981; Westley & Vredenburg, 1991). Negotiated order refers to an organizational context in actors continually negotiate their social and working relationships in order to maintain order (Strauss, 1978; Strauss et al., 1963). Applied to the inter-organizational domain, a negotiated order implies a set of actors collectively negotiating and renegotiating agreements to govern their interactions with respect to the domain.The development of a domain as a temporary negotiated order depends upon actors collaborating to gain a broader appreciation of the problems they face and to make progress which could have not been possible by any actor working alone (Gray, 1989; Trist, 1983). Following Gray (1989), we define collaboration in this research as:a process by which actors o f an inter-organizational domain work together to gain a broader appreciation o f the domain-level problem and reach joint agreements with respect to it and the future direction o f the domain. A domain level problem is that problem area which needs to be resolved within the domain, and which gives the domain its identity.Domain-level problems usually defy a clear definition, which implies that it is not possible to speak of ‘the problem’. Rather, it is more appropriate to speak of domain actors confronted by a ‘problematic situation’ or ‘problematic consisting of clusters of interconnected problems, and which no single actor can solve unilaterally (Gray, 1989; McCann, 1983; Milward, 1982; Trist, 1983). Gray (1989, p. 10) characterizes such domain-level problems as follows:■ The problems are ill-defined, or there is disagreement about how they should be defined; ■ The problems are often characterized by complexity and uncertainty;■ existing processes for addressing the problems have proved insufficient and may even exacerbate them;■ Several stakeholders have a vested interest in the problems and are interdependent;■ These stakeholders are not necessarily identified a priori or organized in any systematic way;■ Incremental or unilateral efforts to deal with the problems typically produce less than satisfactory results;■ Differing perspectives on the problems often lead to adversarial relationships and conflict among the stakeholders;■ Stakeholders may have different levels of expertise and different access to information about their problematic situations; and,■ there may be a disparity of power resources for dealing with the problems among the stakeholders.Two simultaneous conditions seem to be essential for collaboration to be initiated. First, actors must have a high stake in the outcome of the collaboration. The stakes of actors are related to the fundamental interests of the firm such as efficiency, environmental stability and legitimacy (Oliver, 1990). Second, it is also necessary that actors perceive a high degree of interdependency with other actors of the domain for dealing with the domain-level problem (Gray, 1989; Oliver, 1990). Interdependency is associated with the notions of reciprocity and asymmetry (Oliver, 1990). Reciprocity is based on the social norm that one has an obligation to contribute in order to receive benefits. Reciprocity occurs when actors recognize that mutually beneficial results can be achieved through collaboration. By contrast, asymmetry is based on resource interdependencies among actors. Actors initiate collaboration in an attempt to control their interdependencies with other actors of the domain (Aldrich, 1976; Benson, 1975; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978).Once actors perceive the need to collaborate, the process of collaboration is initiated. This process can be understood as constituted by three phases: problem setting, direction setting and implementation (Gray, 1989; McCann, 1983). The problem setting phase involves the exploration of the domain-level problem and identification of those actors with a stake in it; the direction setting phase comprises the development of agreements about valued, shared goals and actions. These first two phases essentially require domain actors to engage in dialogue (to be discussed later) whereby the domain-level problem is addressed. Finally, in the implementation phase, steps are taken to ensure follow-through on the agreements reached if formal collective mechanisms have been created.A significant aspect of the collaboration process by which an inter-organizational domain is developed relates to how power is mobilized by actors to influence the domain (e.g. Agranoff & McGuire, 2001; Gray, 1985; Gray & Hay, 1986; Mayo & Taylor, 2001). Gray (1989), for example, distinguishes four types of power which can be mobilized to influence the development of the domain: power to mobilize, power to organize, power to control the agenda and information, and power to influence or authorize action.The power to mobilize is expressed through the capacity of actors to mobilize resources in order to effectively resist their exclusion from the domain. The power to organize the domain stems from actors’ capacity to shape the boundaries of the domain and create the forums in which domain-level problems are addressed. The power to control the agenda and information is associated with the ability of actors to control how issues and information are addressed within the domain. Finally, actors with power to exercise influence or authorize action will ensure that joint agreements will be successfully implemented. Actors with more power can be expected to use it to construct the domain to their advantage (e.g. Benson, 1975; Brown, 1980; Hardy, 1994a; O'Toole & O'Toole, 1981). As Hardy and Phillips (1998) argue, if actors have a stake in the domain, and the domain is socially constructed, then “it is in the interests of each stakeholder to do everything possible to ensure that the domain is constructed in a way that affords it the most advantage”.One way in which stakeholders can influence the construction of the domain is by (re) defining the problems that constitute the domain. These problems are not objectively present in the domain but are shared as a result of social interaction among the domain actors. They are defined through conversational processes which create meaning for them (Eden et al., 1996; Ford & Ford, 1995; Hardy, Lawrence, & Grant, 2005).These dialogical processes are essentially problem structuring activities which are influenced by the interest and actions of actors with a stake in the domain. The way in which a problem is structured and defined has important implications for the subsequent direction of the domain. For it limits the potential nature and outcome of inter-organizational interaction and plays an important role in determining who participates in the development of the domain (Gray, 1989; Hardy 1994). For example, a particular problem definition may lead actors with a stake in the domain to form coalitions so that certain participants can be included or excluded from the domain (Eden, 1996). Problem structuring, therefore, is a significant mechanism through which stakeholders can exercise power and influence the construction and development of the domain.It has been argued that the participation of stakeholders in the construction of the domain depends upon the perceived ‘legitimacy’ of stakeholders. However, in spite of the reported success of PSMs applications with collaborative groups, no theoretical arguments justifying the appropriateness of PSMs in this context have been advanced so far. In particular, no theoretical models have been presented concerning how dialogue about the domain-level problem is facilitated by PSMs during collaboration. Furthermore, it is not clear whether PSMs are capable of handling asymmetrical power relations among actors (Jackson, 2000; Willmott, 1989). There is therefore a case for investigating the potential of PSMs in assisting actors who engage in collaboration to address a domain-level problem and reach agreements with respect to it, which in turn may contribute to the development of the inter-organizational domain as a temporary negotiated order. This investigation may also contribute to the assessment of the role that PSMs may have in handling power dynamics among actors during collaboration.

2. Review of Literature

- There are a number of key concepts which emerge, explicitly or implicitly, in the literature of both inter-organizational domains and PSMs, and which need to be clearly understood in order to formulate the research strategy appropriately and unambiguously. These concepts are ‘Shared meaning’, ‘power’, and ‘dialogue’, and will be developed in the following sections.

2.1. Meaning and Shared Meaning

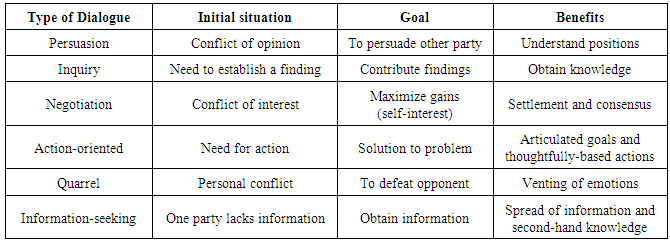

- The importance given to the concepts of meaning and shared meaning in the literature stems from the need to understand how groups make collective sense of their experiences and how they come to take coordinated action. It is commonly held that individuals act in an organised fashion as a result of sharing a common set of meanings or interpretations of their joint experience (Pfeffer, 1981; Smircich, 1983). There are two perspectives in this regard: A. as a cognitive phenomenon, drawing principally on the phenomenological work of Schutz (1967); and B. as a relational phenomena (that is, as a system of interrelated concepts).A. Meaning and shared meaning as cognitive phenomenaA cornerstone of phenomenology is the notion that all meaning and knowledge is rooted in the subjective view of the individual (Schutz, 1967). Meaning can only be understood from the point of view of the individual who assigns idiosyncratic meanings to his or her experiences of the world. The personal meaning an experience has for an individual arises from the relationship between the meanings created through personal experience and those created through social interaction between individuals (Huspek & Kendall, 1991).According to phenomenologists, all meaning results from a conscious individual directing attention towards objects in his or her own world. Thus meaning emerges as a relationship or dialogue between subject and object, perceiver and perceived in consciousness (Stewart, 1978). Working principally from the foundations laid by Weber (1964), Schutz (1967) attempted to clarify the process of creating meaning through personal experience.According to Schutz, human beings have three levels of experience, of which the latter two are considered ‘meaningful’. The first level of experience is a prephenomenological ‘lived experience’. It represents an undifferentiated stream of continuous, transitional experiences each melting into another. This stream of experience has no contours, no boundaries and no differentiations, and is therefore meaningless.At the second level, we step outside the stream of experience and direct conscious attention back towards it. This act of reflection marks the undifferentiated stream of experience into phases, thus dividing, classifying and differentiating it into objects of attention to which the individual assigns meaning. Schutz (1967) argues that the particular kind of attention we give at the moment of reflection gives the new differentiated stream of experience a particular meaning. Thus personal meaning is not purely subjective, as our conscious attention is always directed towards some object, nor it is purely objective, as we provide our own modifications to the stream of experience.Finally, at the third level of experience, personal meanings can be synthesized into an ‘interpretive scheme’ or ‘schema’. Schemas are devices that we use to interpret future experiences. For example, several negative experiences with small planes may be synthesized into a larger schema that will indicate the attitudes (or meanings) taken towards different types and sizes of aircraft. In other words, the schema synthesizes earlier meanings and is used as an organizing structure to classify and give meaning to future experiences. This process of ordering experiences under schemas by means of synthesis is what Schutz (1967) terms interpretation: “Interpretation...is the referral of the unknown to the known, of that which is apprehended in the glance of attention to the schemes of experiences” (Schutz, 1967 p. 84).Related to, but analytically distinct from personal meaning, is shared meaning. According to Gray et al (1986), shared meaning emerges when, during the course of regular social interaction, members of a group begin to favor one interpretation over another. In this way, group members generate coincident expectations about patterns of reciprocal behavior. Repeated confirmation (by oneself and by others) that these reciprocal behaviors produce the anticipated outcomes leads members to assign meaning to the behavior. When several members are guided by similar meanings about the anticipated consequences of behavior, it is said that a ‘constitutive rule’ governs behavior. These constitutive rules are analogous to Schutz’s (1967) concept of interpretive schema in that groups of individuals may share constitutive rules to organize their experiences and make them meaningful within larger schemes. Shared meaning then, is facilitated to the degree that individuals employ similar interpretative schemas or constitutive rules for ordering and interpreting their experiences.The emergence of shared meaning not only involves the use of similar interpretive schemas or constitutive rules. It has been argued that meaning creation also involves what Epstein (1979) terms ‘valuing’. That is, the connecting of our interpretive schemes with our value systems. These value systems are not manifest in everyday communication but constitute tacit structures, and therefore, are not necessarily part of conscious awareness (Habermas, 1971). This notion of valuing is expressed slightly different by Vickers (1965): “Judgments of value give meaning to judgment of reality” (Vickers, 1965). It is important to note, however, that shared meaning is not created in a political vacuum. Actors will compete to instill their own interpretive schemes and value systems.B. Meaning and shared meaning as relational phenomenaFrom a relational perspective, meaning is encoded in the form of concepts. Concepts result from a categorization process by which we group similar experiences. It has been suggested that concepts are classes of objects that can be defined by identifying one or more properties common to all members of that class (Rosch et al., 1976). For example, males are distinguished from females and triangles from squares in this way.Initially concepts arise through the direct assignment of an object or event to a (superordinate) category through the use of the category’s label. Repeated use of the concept label among members of a speech community confirms its coincident denotative value and establishes the basis for communication and regularity in social relations, because the meaning of these concepts is normally taken to remain constant.It should be noted that most concepts cannot be defined by properties alone. Some members of a category may have no properties in common, but instead derive similarity by sharing a gestalt (Miall, 1982). For concepts of this type, context is central to their definition. That is, they are only understood in relation to other concepts referred to in the same context. Concepts assume clearer meaning the more the context is specified. Contextual clues are frequently necessary to select the appropriate concept in the first place, and beyond that, contextual clues elaborate the meaning an individual attaches to a concept. Hence, the meaning of a concept resides not only in its properties but also in its pattern of relations with other concepts present in a particular context.As a result, the content and the meaning of a concept are particular to an individual and to a situation. Since the meaning of a concept flows from its embeddedness in a network of other concepts, obtaining shared meaning among individuals would imply the use of similar networks of concepts. The degree of similarity between these networks has been extensively explored in terms of comparing individuals’ cognitive maps (Eden & Ackermann, 1996; Huff & Jenkins, 2002; Weick & Bougon, 1986). A cognitive map consists of the set of concepts and their interrelations which an individual uses to understand a particular situation (Weick & Bougon, 1986). The assembling of several individual cognitive maps results in a collective map. It is this collective map that is usually associated with shared meaning (Eden & Ackermann, 1996; Weick & Bougon, 1986).An example of a cognitive map as a network of nodes and links is shown in (Figure 1). It shall be mentioned that the creation of shared meaning is a political process and actors’ power (or lack of power) will affect their ability to participate effectively in this process.

| Figure 1. A cognitive map as a network of nodes and links |

2.2. Power

- Power is a complex, multidimensional concept which has received a variety of theoretical conceptualisations. Among the different approaches proposed for the analysis of power are those of Pfeffer (1981), Hardy (1985), Boulding (1989). In broad terms, power can be conceived as the ability to affect the behaviour of others in a conscious and deliberate way. This definition implies that coercion, manipulation, authority, persuasion and influence are all expressions of power.A. Three dimensions o f powerLukes (1974) linked the first dimension of power to the work of the pluralists. The focus here is on the decision-making process. The powerful are those who are able to influence this process in order to obtain the decision outcomes they want. Three main assumptions underlie the one-dimensional view of power. Firstly, it is assumed that individuals are aware of their grievances and act upon them by participating in the decision making process and using their influence to determine key decisions. Secondly, the exercise of power is assumed to occur only in decisions where conflict is clearly observable. Finally, it is assumed that conflict is resolved during the decision making process. In summary, the first-dimensional view of power focuses on the overt exercise of power in the decision-making arena.Lukes’ (1974) three dimensions of power clearly illustrate the developments in the way power has been studied. Luke’s (1974) third dimension is particularly important for this research because it specifically addresses the issue of power to Implicit in the formulations that have been discussed so far is the existence or availability of power sources to actors if they were to exert power. B. Sources o f powerThe most evident sources of instrumental power are grounded in differential access to scarce or critical resources. Because resources are differentially distributed, some actors are dependent upon others for access to them. Dependency relations confer power on those providing resources to others (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). The successful control and management of these resources allows actors to influence decisions, agendas, resource allocations and the implementation of decisions. For example, the ownership of land and control of information have been found to be particularly important sources of instrumental power (Boulding, 1989; Galbraith, 1986; Lukes, 1986; Pfeffer, 1981). Instrumental power has been related to the ability to control uncertainty (Pfeffer, 1981). Credibility, stature, prestige, charisma and personal appeal can also confer instrumental power (Lukes, 1986; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1974; Salancik & Pfeffer, 1974; Wrong, 1995). Other sources of instrumental power include access to and contacts with higher echelons or decision-making bodies and the control of money, rewards and sanctions.Mere possession of scarce resources does not in itself confer instrumental power. Actors must also be aware of them, and able to control and tactically use them if they are to be successful in achieving desired outcomes (Bums & Stalker, 1961).The instrumental (first and second dimensions) and symbolic (third dimension) aspects of power all involve deliberate conscious strategies on the part of the actors to mobilize power, thereby achieving their objectives either by defeating or circumventing opponents. In recent years, however, a number of developments have occurred in the study of power, which led some scholars to suggest the existence of a fourth dimension. This dimension draws attention to another aspect of power which may produce certain advantages and disadvantages for actors without being consciously mobilized. This aspect of power lies in the power of the ‘system’ which causes the unconscious acceptance of the values, traditions, cultures and structures of a given institution or society. This aspect of power is discussed next.C. The power o f the systemThe work of Foucault (1977; 1980; 1982; 1984) emphasises the power of the system and the degree to which all actors are limited in resisting, much less transforming that system (Knights & Morgan, 1991; Knights & Willmott, 1989). Foucault contests the concept of autonomous power that underpins the first three dimensions. He rejects the idea of an isolated agent who possesses and mobilises a battery of power sources that can be used to produce particular outcomes. Instead, he conceptualises power as a network of relations and discourses 8 which captures advantaged and disadvantaged alike in its web. Actors may have intentions concerning outcomes, and may mobilize resources or engage in the management of meaning with the idea of achieving them, but using these power sources does not necessarily produced these desired outcomes. “People know what they do; they frequently know why they do what they do; but what they don’t know is what what they do does” (Foucault, 1977).According to this view then, power is no longer a resource under the control of autonomous, sovereign actors. Instead, all actors are subject to ‘disciplinary power’, a prevailing web of power relations which resides in every perception, judgement and act, and from which the prospects of escape are limited for dominant and subordinate groups alike. This means that prevailing discourses embedded in the system are experienced as reality, and alternative discourses are difficult to conceive of, let alone enact. Actors will more commonly engage in attempts to refute, challenge, modify or amend existing (rather than adopt or propose alternative) discourses, thus reinforcing existing power relations. This is aptly illustrated by the prevailing discourse embodied in corporate strategy. The concept of corporate strategy which pervades contemporary management empowers those managers with strategic responsibilities and skills or those who form successful strategies by: (1) facilitating and legitimising their exercise of power; (2) proving a rationalisation of their successes and failures; and (3) conferring on them a corporate identity and role (Knights & Morgan, 1991).Some groups are disabled by the prevailing set of power relations: managers in personnel management have not benefited from the focus on strategy. This has led, for example, to the transformation of personnel into human resources management and an emphasis on the link between strategy and human resources. Similarly, some operational research (OR) publications now emphasise the role operational research can play in strategy making (Eden & Ackerman, 1996). In other words, groups trying to resist the prevailing set of power relations, or discourse, embodied in corporate strategy may inadvertently reaffirm it.In summary, power can be seen as working at four different levels. On the surface, power is exercised through the mobilisation of scarce resources, and through the control of decision making processes. At a deeper level, power is exercised by managing the meanings that shape others’ lives. Deeper still, is the suggestion that power is embedded in the very fabric of the system; it constrains how we see, what we see, and how we think, in ways that limit our capacity for resistance. Collaboration does not take place in a political vacuum but within a domain in which a certain distribution of power is already deep-rooted (fourth dimension).

2.3. Dialogue

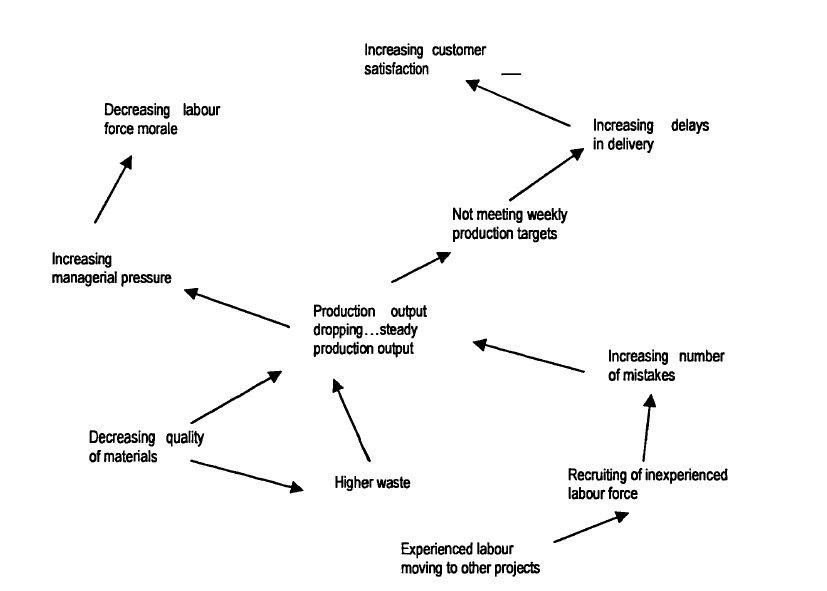

- In general terms, dialogue is what happens when two or more participants have a communicative encounter. More precisely, Walton (1992) defines dialogue as “a process of communication among two or more persons through a series of back and forth messages, in which these messages are organized in a sequence towards fulfilling a goal” (Walton, 1992, Denhardt, 2011). Habermas (1970; 1984) refers to these back and forth messages as ‘speech acts’. He distinguishes five types of speech acts: imperative, constative, regulative, expressive and commissive.Imperatives are used to influence the will of another (a request or a suggestion). Constatives serve to assert a truth claim (an assertion or a statement). Regulatives govern or regulate through a moral code (forbid, allow, warn) the interpersonal relationship between speaker and listener. In expressives a participant reveals his or her subjective thoughts or identity (thanks, apologize, welcome). And commissives are used to assure, affirm or deny claims.Particularly useful in the discussion of dialogue that follows will be the typology developed by Walton (1992; 1998), who distinguishes six different types of dialogue depending upon the initial situation from which the dialogue arises, the goal of the dialogue, and the expected benefits of the dialogue (see Table 1).

|

3. Research Methodology

- The present study is a basic research with respect to orientation, and exploratory considering its objectives. The research method is descriptive-analytical, content analysis. Content reveals important information on data and research question and presents the meaning of the pattern inherent in a set of data (Brown & Clark, 2006, pp. 77-101). Also, content is an implicit pattern of data which describes and classifies observations and interprets different aspects of the phenomenon (Boyatzis, 1998, 0. 4). Generally speaking, content is a repeating and distinguishing feature of the text or observation which offers a specific understanding and experience of research questions (King & Harouk, 2010, p. 150). This method is a process for analysis of textual data which transforms disparate and different data into rich and comprehensive ones. In general, content analysis is a method for:a. Understanding seemingly irrelevant informationb. Analyzing qualitative datac. Systematic observation of the individual, relationship, group, organization, and cultured. Changing qualitative data to quantitative ones The technique used for data collection is semi-structured interview. The statistical population of the study consists of researchers and experts of public administration, political sciences, sociology, economics, law, and other related fields. In the present study, the experts were selected through non-probability sampling and a combination of purposeful and snowball methods. Snowball is one of the common methods in consecutive sampling. In this method, the researcher first identifies a person, and after obtaining information, asks them to introduce other persons. This process continues so as to reach consensus and saturation of ideas (Orili & Parker, 2012, pp. 190-7). In this study, 20 interviews were conducted to obtain information and reach the saturation point. Accordingly, first 16 experts were chosen to participate in the study. All those people were faculty members of universities or research institutes expert in health policies and health sector and had published highly-cited papers or books or had led and conducted well-known research projects in relevant areas. Although the information obtained after the 12th interview seemed redundant, the interviews continued up to the 16th one to make sure of collecting all information, reaching saturation point and consensus. Also, considering the nature of the study, i.e. content analysis, the reliability and validity of the questions and interviews in saturation point are taken for granted.The analysis of interviews could prove the very fact that expert reached consensus on three terms Dialogue, Domain (Shared meaning) and power. In order to use these three concepts as sub-areas to reach collaboration, Gray’s (1989) three phased model of collaboration besides Eden’s (1982; 1986) model of group problem solving and Hardy’s (1985; 1994b) model of power were used to create the conceptual model whose sub-areas focus on Dialogue, Domain(Shared meaning) and power , which was the sum of all interviews.

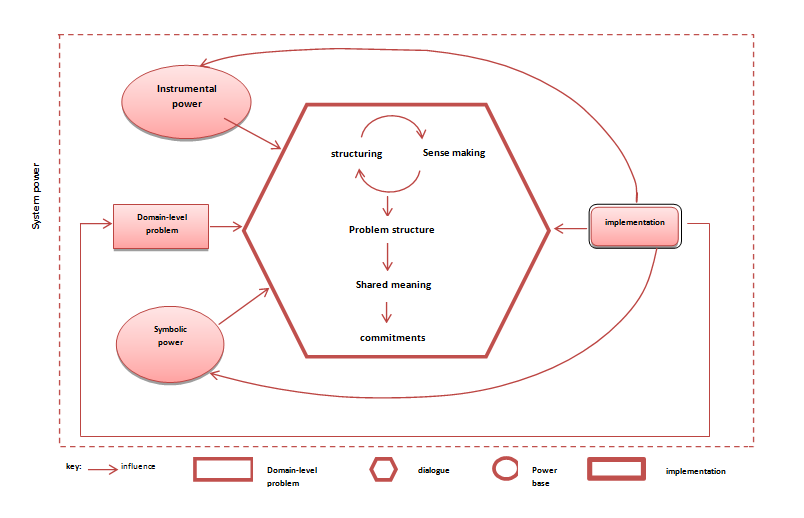

4. Overview of the Conceptual Model

- The sub-areas which make up the model are domain, power base, dialogue, and implementation. The interrelations between the different sub-areas which constitute the conceptual model are represented diagrammatically in (Figure 2). This figure illustrates only the general structure of the model. The sub-areas and the relationships between them require some introductory explanation, in preparation for a more detailed discussion of the elements within them which will be provided.

| Figure 2. The conceptual model of this study to reach collaboration |

5. Application of the Conceptual Model in a Real Case

- Having identified the reasons why a positivist approach to research design was infeasible, an action research approach was adopted for exploring whether the potential role that had been identified in principle was reliable in practice. A case study drawn from an action research project in research center of shahid Beheshti medical school in Iran was undertaken as a vehicle for exploring the adequacy of the conceptual model developed. The principal aim of the action research project was to contribute to building a high value environment, which is typically characterized by strong adversarial relations. These characteristics led to the development of a cross-organizational learning approach (COLA). The focus of the action research project on the health industry led to selection of three teams to participate in workshops to see how different actors play their roles in problem structuring phase. The core data generated from the application of COLA with these three teams comprised responses by the team members to a post-workshop questionnaire based on the competing values approach (CVA) to group decision process effectiveness, and transcripts of semi-structured, taped-recorded, post workshop interviews with the team members. Analysis of the questionnaire responses provided useful background information which subsequently informed the focus of the post-workshop interviews. Finally, the model proved to be effective and the emergent theoretical framework ,after this stage contained four analytical categories or ‘themes’ representing four stages in a partnership cycle: starting conditions, interacting, negotiating and adjusting.

6. Conclusions

- The focus of this research was finding a way to reach higher level of collaboration in multi-organizational contexts. In order to avoid ambiguity in addressing this issue, several key concepts commonly found in the literatures on multi-organizational collaboration required clarification before beginning the interviews with scholars and experts. These were shared meaning, power and dialogue. Using this clarification as a starting point, the interviews were completed in order to design a conceptual model. The conceptual model relates the redefined concepts to the processes by which the intended products of collaboration are achieved. Dialogue was found to be the principal process element where this analytical assistance would be expected to play a significant role. Using this model in our case study proved to be helpful in reaching collaboration. Fortunately, a lot of problem structuring methods have this potential to improve the quality of the dialogue between actors who engage in collaboration to address a problem of common interest; to impact positively on the ownership of the commitments achieved during dialogue; and to facilitate mutual accommodations in the power balance among actors during and after dialogue to maximize collaboration in policy making, implementing and evaluating.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML