-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2016; 6(1): 21-28

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20160601.03

Entrepreneurship Barriers and Entrepreneurial Inclination in Lebanon

Sam El Nemar 1, Khalil Ghazzawi 2, Safwan El Danaoui 2, Samer Tout 3, Hassan Dennaoui 4

1School of Business, Lebanese International University, Lebanon

2Management Department, Faculty of Business, Lebanese University, Tripoli Branch, Lebanon

3Finance Department, Faculty of Business, Lebanese University, Tripoli Branch, Lebanon

4MIS Department, Faculty of Business, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

Correspondence to: Khalil Ghazzawi , Management Department, Faculty of Business, Lebanese University, Tripoli Branch, Lebanon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Purpose: The aim of this study is to identify and measure the barriers to entrepreneurship in Lebanon based on one dependent variable and several independents variables. Theory suggests that there are four main factors that significantly affect entrepreneurial inclination. Those factors are: social network, lack of funding, risk and hard work tolerance and economic and political stability. Social networks, relationships, connections, and contacts encourage entrepreneurs to start business in Lebanon. However, such business launching is hindered by lack of funding where Risk and hard work tolerance can affect as well entrepreneurship. Some people are averse to risk and prefer low risk situations, which may hinder entrepreneurship. Finally, economic and political stability can encourage entrepreneurs to start their own business. Design/methodology/approach: The survey based methodology scope: 100 participants took part in this survey data collection; university students, employees and business owners. The data analysis methods employed was multiple-item survey instruments; questionnaires, and secondary data, to identify and assess the reason that will encourage people to open a new business and become entrepreneurs. Data includes information on family background, education, as well as income. Findings: The paper findings revealed that there are several factors that prevent entrepreneurs from opening new businesses in Lebanon, which are Social network that encourage people to think seriously to open new business, Lack of Funds, Fear of Hard work and Risk, Economic and Political factors affecting new business.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship Barriers, Entrepreneurship Inclination, Business Environment Lebanon

Cite this paper: Sam El Nemar , Khalil Ghazzawi , Safwan El Danaoui , Samer Tout , Hassan Dennaoui , Entrepreneurship Barriers and Entrepreneurial Inclination in Lebanon, Management, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 21-28. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20160601.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Entrepreneurship has attracted increasing attention in recent years in the light of concrete evidence of the importance new business creation to the economic growth and development (Acs et al., 2005; Langowitz and Minniti, 2007), with a belief that individuals with entrepreneurial skills and abilities will create benefits at different levels of society (European Commission, 2003). Entrepreneurs bring new ideas to life through innovation, creativity and the desire to build something of lasting value (Volkmann et al., 2009). Entrepreneurs are people who show initiative, imagination, creativity and flexibility, and are, also willing to think conceptually and to see change as an opportunity (Bygrave, 1998). They have their ways of dealing with opportunities, setbacks and uncertainties to "creatively create" new product, new services new organizations and new ways of satisfying customers or doing business. In addition, as societies, their people, and their tastes change, entrepreneurs function as an evolutionary force by adapting their businesses to meet those changes (Giunipero et al., 2005) because rigidity in the face of change would only lead to business failure (Zimmerer and Scarborough, 2002). Variation exists in the nature and number of personal facets which can be ascribed to the potential entrepreneur, including such characteristics as creativity, temperament, teamwork sociability, risk taking, flexibility, growth orientation (Macke and Markley, 2003; Thompson, 2004), desirability, intention (Guerrero et al,. 2008), locus of control, and innovativeness (Mueller and Thomas, 2001). Clearly, several of these characteristics will be found in many successful, enterprising achievers. But many people with these traits and characteristics will not become entrepreneurs.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Factors Affecting Entrepreneurship

- The most popular arguments in entrepreneurship research have traditionally revolved around micro-level factors including opportunity recognition, motivation, financing and performance. Opportunity identification is considered a mainstream fundamental issue in entrepreneurship research, given that it is an important entrepreneurial capability and a source of competitive advantage (DeTienne and Chandler, 2004). As well, opportunity identification has been linked to differences in human capital variables including education and work experience, higher levels of prior industry or entrepreneurial experience as well as experience in managing employees (Carter et al., 2003; Carter and Williams 2003). However, despite the recognition that education and prior entrepreneurial experiences influence people’s attitudes towards starting their own business, the impact of entrepreneurship education on intentions to found a business has remained relatively untested (Donckels, 1991; Krueger et al., 1994). In relation to financing, the evidence generally reveals that entrepreneurs start with lower levels of overall capitalization and lower ratios of debt finance (Bruin et al., 2007). Entrepreneurial ventures also tend to be concentrated in service sectors that are usually cheaper and easier to establish (Carter et al., 2003) and both male and female entrepreneurs tend to tap mostly into savings and family support as suggested by Cosh et al., 2000. Entrepreneurship is also related to the level of economic development and is embedded in a specific national economic context. For example, high levels of self-employment are often reported in countries with low levels of economic development (Baughn et al., 2006). Similarly, the evidence tends to suggest that increasing economic prosperity is associated with decreasing rates of self-employment (given the increased attractiveness of wage employment as well as the opportunity cost of self-employment), although this may not apply to the most prosperous countries (Nooderhaven et al., 2004). Accumulated data through the GEM project indeed support the existence of a curvilinear relationship between GDP and entrepreneurial activity, with the highest levels of activity reported in less prosperous nations (motivated by push factors) and the lowest levels of entrepreneurial activity reported in the middle income nations (Acs et al., 2005); (Baughn et al., 2006).

2.2. Effect of Entrepreneurship

- Studies have shown that permanence and employment longevity is no longer a significant feature of career paths (Fallows et al., 2000) and the changing nature of career prospects in large organizations has resulted in graduates becoming more interested in starting their own business. However, difficulty in finding stable employment is not an enough strong factor that will lead to graduates becoming entrepreneurs. This research was fully employed and such failure can be seen as degrading. Postgraduate students in Malaysia were also found to be averse to stress and hard work and these factors negatively effects entrepreneurial inclination. This finding confirms a previous research conducted among undergraduates in the UK (Henderson et al., 1999). Research on the impact and effects of entrepreneurship education has not kept pace with the growth of teaching capacity. The assertion that entrepreneurship education leads to increased entrepreneurial intentions and therefore to more new venture formation may seem intuitive. A growing academic interest in entrepreneurship has developed alongside different economic changes, such as globalization (Gummesson, 2002) and the acceleration of technological development (Santoro and al., 2002). This has led to rapid improvements in the competitive environment with organizations desperately needing to adapt to these changes and develop innovative products, services, processes and business models. However, only a few studies have investigated entrepreneurial attitudes at specific universities (Luthje and Franke, 2003; Lee and Wong, 2003; Teixeira and Forte, 2009). This primary research found a significant scope for promotion of entrepreneurship in the education system across the globe. In UAE, the female students have immense interest in starting their own new ventures. In other words, for many entrepreneurs, the choice of self-employment may reflect the restricted structure of opportunities in the labor market, labor market discrimination or glass ceiling career problems, with self-employment often perceived as a survival strategy, or as a means of providing flexibility in work scheduling and reconciling multiple roles (Baughn et al., 2006). The contribution of entrepreneurship towards job creation has been well recognized by the young students. In times of recession when there is a reduction in employment opportunities globally, this study is very important since results show that the new generation is positively thinking about alternative ways of creating new jobs (Bell-Rose and Payzant, 2008). The results indicate that students from developing/emerging economies are more likely to envisage future careers as entrepreneurs and are more positive towards entrepreneurship than their industrialized European counterparts, even though motivators for employment / self-employment are similar across the samples. The type of role models used and the extent of entrepreneurial experience have varied between individual countries (European Commission, 2003). Given the potentially important economic and social effects of the creation of new enterprise, it has become critical to understand the environmental determinants. What conditions favor business start-ups and what conditions hamper them? Several conceptual models are available. At the micro-level, many disciplines including economics, psychology, and sociology have developed occupational choice models for understanding entrepreneurial decisions (Acs and Audretsch, 2003). Some studies have shown that the institutional environment affects entrepreneurial firms in various ways such as its effect on risk related decisions among managers (Makhija and Stewart, 2002).

2.3. Barriers of Entrepreneurship

- Enterprising people translate “what is possible” into reality (Kao, 1989). First, we should know that entrepreneurship is invariably associated with risk; entrepreneurs are prone to fail in the risk management examination because they are always based on hope more than judgment (Derr, 1982). Risk adversity can be a general barrier that hinders entrepreneurship everywhere where it is known that not all entrepreneurs can handle risk positively. Second, the 2009 index of economic freedom cited key problems of political interference as well as the complicated process of dismissing employees as a hindrance to economic flexibility and entrepreneurship (Doing Business, 2012). As known employing and dismissing employees is difficult, expensive, and hinders flexibility and limits entrepreneurial growth; Lebanon is ranked the 90 among 181 countries studied. Therefore, inflexible labor relations are considered worldwide and in Lebanon as a common barrier for entrepreneurial growth. Global barrier is worldwide recession, although entrepreneurs typically emerge during a recession, the difficulties of starting a business may deter such start-ups. Today’s worldwide recession will continue to slow business growth, threaten entrepreneurial skills, and innovation worldwide. “Brain drain” is another barrier for entrepreneurship in Lebanon and third world countries where “brains "are diffused from Lebanon to neighboring/gulf countries which threaten entrepreneurship activity in Lebanon. Political instability is a cause of brain drain that occurs in Lebanon, especially after the internal conflict (2007) and Israeli war (2006). Entrepreneurship is heavily damaged in Lebanon because of political instability, and capital owners live in continuous state of ever-changing “game rules”. Another barrier to entrepreneurship activity is corruption, copyright problems, and the informal economy. Lebanon faces hindering entrepreneurship because of excess illegal production, lack of adherence to copyright laws, and an active informal “black market” economy. Illegal economy weakens entrepreneurial spirit in capital owners and represents a strain on public sector that must allocate a substantial part of its budget to care for retired workers who never contributed to the social security system (Bertranou, 2007). Lebanon ranks 134 in the most corrupted countries worldwide and of 2.5 score in a (1 to 10) scale resembling corruptness (Transparency International, 2011). Another issue hindering entrepreneurship in Lebanon is procedures and financing, which is stated by The World Bank Group. The previous group enlists several bureaucratic and legal hurdles an entrepreneur must overcome in order to incorporate and register a new firm, along with their associated time and set-up costs: Designate a Lebanese lawyer, deposit capital in a bank and obtain a certificate of deposit, register the company with the company registry, notify ministry of finance about the commencement of operations, and register at the National Social Security Fund. Unsurprisingly, Lebanon ranked 103, way behind Egypt (18) and slightly ahead of Jordan (127). Countries that vied for top position included, by chronological order, New Zealand, Australia, Canada and Singapore. What did they have, that we didn’t? For one: no capital requirements, no registration fees, and short procedures and days to be completed. Entrepreneurship plays a vital role in revitalizing local and global economies and is the only way to drive markets towards prosperity, especially during economic downturns. Fostering entrepreneurship is not only about education and inspiration; it is high time we unleash the potential of our entrepreneurs, by setting them free from hurdles, impediments, bureaucratic headaches and barriers. Moreover, we have to mention that lack of national unity is another frequently mentioned barrier in the country’s low self-image and citizen’s lack of national pride. This may seem not attached to entrepreneurship development, but on a second thought clusters, heritage, and interests differ sharply in Lebanese provinces, particularly between population inside the capital or major coastal cities, and the rest of population in isolated agrarian-based provinces. Such theory would be proved when we see that differences may make it more difficult for entrepreneurs to develop a standard product for the entire country. In addition, differentiated products or services may not find a large enough in-country market segment to be profitable for entrepreneurs. Finally, if we group firms that are located in Lebanon, we can find the firms in the traditional and local clusters (which is frequently abundant in Lebanese market) needs assistance with marketing and promotions to better compete with the other more progressive entrepreneurial clusters, including foreign-owned firms, using state-of-the-art business and marketing practices. Lack of international marketing expertise will damage the progression of entrepreneurial firms and clusters in third world markets.

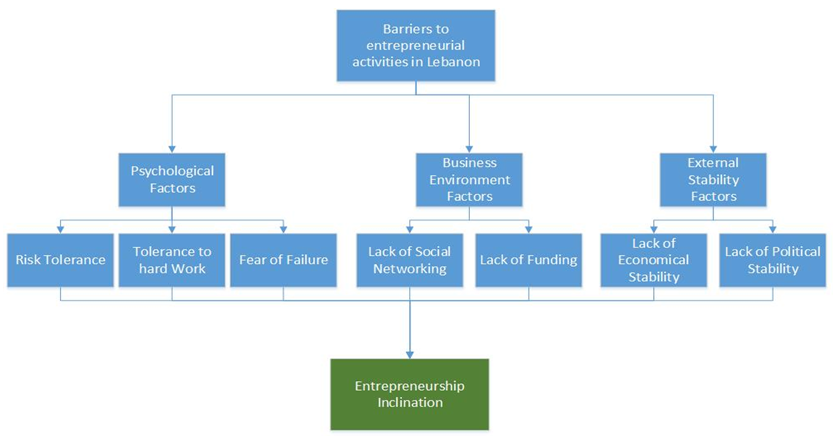

3. Conceptual Framework

- The Model of this study suggests that independent variable related to the psychological factors, business environment and external stability factor have a significant effect on entrepreneurship Inclination. The figure below presents the conceptual framework of this study.

| Figure 1. Conceptual Framework |

4. Data Collection and Sampling

- Data for this study were collected through a survey distributed to university students, employees and business owners from different backgrounds and income level. The questionnaire was designed to study the entrepreneurs in Lebanon, through seven factors: aversion to stress and hard work, aversion to risk, fear of failure, lack of social network, lack of resources and political and economic factors in Lebanon. Raw data from completed scores were entered into an SPSS file for analysis. One hundred and twenty questionnaires were distributed and one hundred responses were successfully obtained. The questionnaire was divided into two sections.

5. Data Analysis

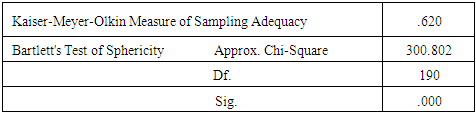

5.1. Kmo and Bartlett's Spherecity Test

- Before conducting factor analysis, we had to determine whether the sample was suitable for this kind of analysis. Therefore, we conducted the Kaiser-Mayer Olkin’s (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy test and Bartlett’s test of Spherecity to appraise the suitability of the data for the factor analysis. The results of the KMO measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test (Table 1) show that the data meet the fundamental requirements for factor analysis. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy is (0.620) a value > 0.5 which indicates that patterns correlation are relatively compact and so factor analysis should yield distinct and reliable factors. The Bartlett measure tests the null hypothesis that the original correlation matrix is an identity matrix. The result showed that the score was highly significant, and the correlation matrix was not an identity matrix. (Sig. = 0.000). Refer to Table 1. Thus the requirements for sample adequacy were met, and we proceeded to conduct factor analysis.

|

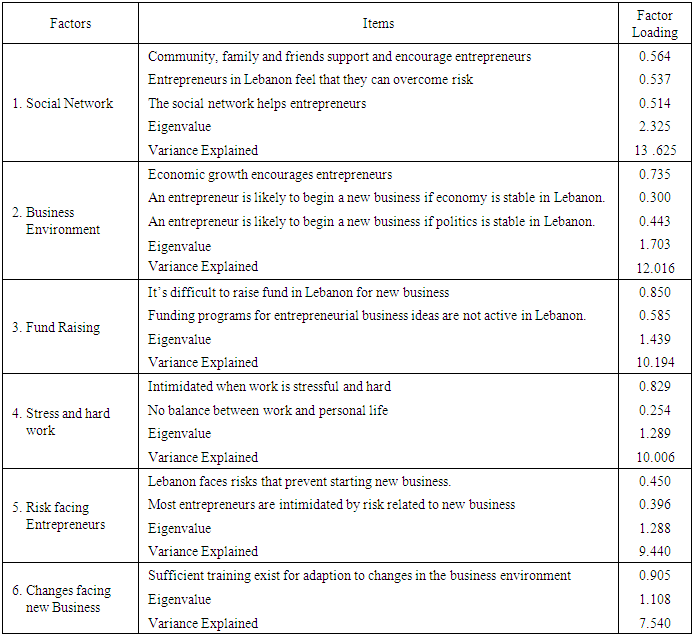

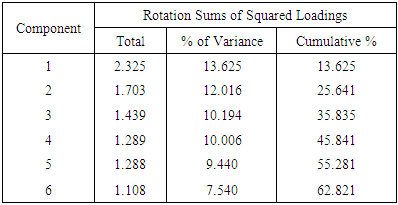

5.2. Factor Analysis

- Factor analysis was run using SPSS 20, and the principal components method was used as an extraction method. Only Eigenvalues greater than one was retained and the Varimax rotation method was used to optimize the loading factor of each item on the extracted components. Items with factor loadings greater than or equal to 0.3 were retained, while those <0.3 were suppressed. The analysis generated nine factors, eight of which were considered representative of distinct barriers, while one was deemed not meaningful and was deleted from the factor set. The retained factors were named 1) social network, 2) stress and hard work, 3) business environment, 4) fund raising, 5) risk facing entrepreneurs, and 6) changes facing new business. Table 2 presents the factors, their loadings, eigenvalues, and associated variance explained.

|

|

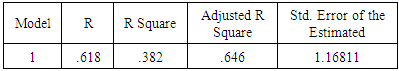

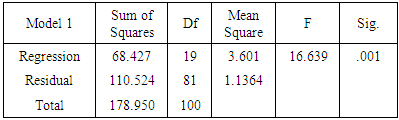

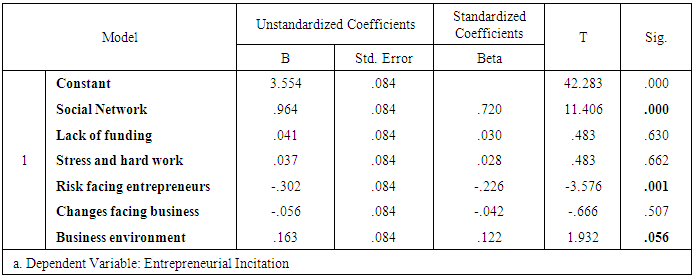

5.3. Regression Analysis

- The purpose of conducting a regression analysis is to determine the importance of each independent variable (from the eight identified meaningful factors) in predicting the dependent variable: entrepreneurial inclination. The beta coefficient of each variable indicates the significance of the variable and the direction of its effect. Regression analysis is run using SPSS 20, and the model summary shows that adjusted R square is 0.618, which means that the suggested model is able to predict about 60% of the change in entrepreneurial inclination. This means that the variables in the linear equation possess powerful predictive power, and that the model itself has strong predictive capability. Table 4 presents the model summary of the regression model.

|

|

|

6. Interpretation of Results

6.1. Lack of Social Network

- The results of the Regression showed that the factor with the greatest influence on entrepreneurial inclination is social network. With a beta coefficient of 0.72, the t-statistic was significant at (Sig. = 0.000). Focusing on Lebanon, this study has shown that Lebanese people feel that social networking plays a critical role in the success of the entrepreneur. This is ingrained in their culture. Thus, this study’s finding regarding the importance of social networking in predicting entrepreneurial inclination in Lebanon seems to be consistent with previous research. Therefore, lack of strong social network may be perceived as a barrier hindering entrepreneurship.

6.2. Risk Facing Entrepreneurs

- Regression analysis conducted in this study showed that tolerance to risk is indeed a factor that has a significant effect on the dependent variable with a significant level of 0.001, but it was clear that since the beta coefficient is negative, the impact of this factor is negatively associated with entrepreneurial inclination, this means that the more risk the individual is, the less his inclination to become an entrepreneur. This is consistent with previous research that identifies risk taking ability as a trait needed for successful entrepreneurs (Dyer, 1994). Thus tolerance to risk may indeed pose as a barrier to entrepreneurship.

6.3. Weak Business Environment

- In this study, regression showed that the business environment is an important factor that can help predict change in entrepreneurial inclination. Its beta coefficient was 0.122 with a marginal significant t-statistic at (Sig. = 0.056) it is essential for the entrepreneurial venture to start in an environment that is conductive to growth and sustainability. Such an environment must have certain building blocks, such as a stable context for doing business, stable exchange rates, taxes, interest rates, regulations and government procedures, active NGO’s that facilitate the business processes of the startup, and provide programs for funding and financing at the time that the startup needs it. This means there should an external infrastructure should exist, both public and private to support the entrepreneurial endeavor. Concerning Lebanon, there are a few initiatives whose main objective is to assist in the finding and developing of entrepreneurs, and finally in turning their ideas into real business activities. One such organization is BADER, whose mission is to provide the necessary tools for the successful launching and development of high impact entrepreneurial projects in Lebanon with the aim to promote national economic development, job creation and a reduction of the brain drain (BADER, 2015). Another such organization is KAFALAT whose objective is to facilitate access to credit for entrepreneurs by granting them guarantees to present to commercial banks. UNIDO is also active in Lebanon through its awareness projects which it carries out in conjunction with the Union of Chambers of Commerce in Lebanon (UNIDO, 2015).

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study showed that there are several factors that prevent entrepreneurs from opening new businesses in Lebanon. The factors that affect mostly in opening new venture are: Social network that encourage people to think seriously to open new business, Lack of Funds, Fear of Hard work and Risk, Economic and Political factors affecting new business. The regression analysis confirms that there is a significant relationship between those factors and being an entrepreneur that is willing to open a new business. In order to encourage entrepreneurs to open a new business, support for the economic growth and development of the country is needed. The government should play a role in creating a competitive business environment for entrepreneurs, for example by supporting the Banks to give loans to entrepreneurs, helping the entrepreneurs by securing their project from any external threats such as war or insecure political situation. This could be done through various ministries and agencies that should work on reducing the factors that prevent the establishment of new businesses.

8. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

- One of the factors identified through factor analysis was the business environment that is conducive to entrepreneurial endeavors. This study was able, through regression analysis, to assess its importance in predicting the dependent variable, but it was not able to comprehensively investigate the elements that go into this factor. For example, it would be useful to investigate what elements of the business environment (consultation centers, financing agencies, establishment offices, etc.) need to be developed and which elements are more valued by entrepreneurs. Another empirical study focusing on this factor would be considered valuable to entrepreneurship research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML