-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2016; 6(1): 9-20

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20160601.02

Analysis of Output Variances: A Forensic Accounting Approach

Nwosu M. Eze

National Institute for Legislative Studies, National Assembly, Abuja, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Nwosu M. Eze, National Institute for Legislative Studies, National Assembly, Abuja, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

With the introduction of the International Standard on Auditing number 240 (ISA240) there is a paradigm shift in auditing. Auditors are required to identify and assess the risks of material misstatements due to fraud at the financial statement level and to evaluate the sufficiency, implementation and the effectiveness of the controls related to those assessed prone to fraud. This, of course, implies that statutory audit must now take the garb of forensic investigations. The problem with the present system of forensic investigation is that it focused more on financial transactions than on the totality of the entity’s operations and often time neglects areas where there have been constant leakages of other organisational resources that are of financial consequences but which are not easily detected with a normal analysis of the financial statement. Determining the extent forensic accounting can detect possible criminal activities concealed in financial account is still a subject of debate in most jurisdiction. This paper attempts to offer suggestions using real case problem on how to apply forensic accounting in investigating variances and suspected fraudulent activities in manufacturing processes. It employs both empirical and supervised experimental modules integrated with the normal audit tools in unearthing fraudulent acts perpetrated over many accounting periods. The paper recommends that forensic accounting is necessary in a manufacturing organization in order to detect fraudulent activities which normal audit cannot detect.

Keywords: Financial Statement, Material Misstatements, Statutory Audit, Forensic Investigations, Forensic Accounting, Manufacturing Processes

Cite this paper: Nwosu M. Eze, Analysis of Output Variances: A Forensic Accounting Approach, Management, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 9-20. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20160601.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction/Literature Review

- Fraud and general impropriety in the management of organisations have become a global problem of late, judging from recent events at both local and international realms. Stealing, pilferage and unauthorised diversion of cash and material resources are among the major forms of fraudulent behaviours associated with organisational failure in Nigeria. Nwaze (2008) quoting the Holy Bible asserts that fraud has been around since the beginning of time and would continue to be an issue till the end of time. He went further to mention some which include the impersonation of Esau by Jacob and the woman who exchanged her dead baby for a living one. In addition to others too numerous to mention, fraudulent activities in Nigeria also include the passing off of property titles in order to dupe potential buyers. Sometimes it is difficult to differentiate between an error and a fraud as some errors, though unintentional, may confer some undue and sometimes irreversible advantage on the wrong party while others may be made with the full intention to defraud. Venables & lmpey) (1985) as cited in Nwaze (2008) classified fraud into the following:i. Theft: The unauthorised taking of another’s possession;ii. Forgery: The falsification of documents; andiii. Manipulation of accounting records or entries. They went further to summarise the principal circumstances that can foster fraud using the acronym COMAS translated as follows:Concealment: The chance of remaining undetected;Opportunity: The right place and right time for the fraudster;Motivation: A personal need or greed;Attraction: A desirable target; andSuccess: The chance of avoiding prosecution.Whilst management and owners in the private sector are making concerted efforts at eliminating or reducing the fraud scourge, the public sector seems not to have made any serious attempt at proffering credible solutions towards this image eating monster.It is true that the major reason for instituting internal control measures such as internal checks and internal audit is to prevent and or discourage fraud (Arens, Elder & Beasley, 2006270). We must also know that external or statutory audits are undertaken to ensure that the internally instituted fraud control mechanisms are adequate in scope, effective in application and complied with. However, it is rather unfortunate to note that the complexity of the human brain and the dynamic method of reasoning have tremendously diversified present day scams away from the hitherto known modes, to fraudulent activities that now render true corporate governance ideals almost unworkable. This is more so since the advent of globalisation and the unrestricted use of the internet and computers in the allocation and control of organisational resources. Though the applications of computers are meant to provide more reliable controls than would be possible with human effort, they are programmed and operated by humans. They may therefore be subject to unauthorised human control which can inadvertently lead to fraudulent manipulations. A recent case is where a system's administrator in one of the banks in Nigeria colluded with an unscrupulous customer to dupe the bank of N50 million. This was done through the manipulation of the computer operations system, which credited the customer’s account with transfers from other customers ‘accounts using fictitious codes to simulate real transaction authorisation codes. This is a confirmation that fraudulent manipulations can only be as sophisticated as the system under the contemplation of such mending manipulators and not less.Fraud is real and has so many branches now that modern day fraudulent activities go undetected for most of the time and/or until it is too late. Forensic accounting is the new branch in accounting auditing which has the sole aim of unearthing fraudulent activities within and outside an organisation so far as the third party's action is in any way reflective on the activities of that organization.However, the current scope of forensic investigation still leaves much to be desired in the area of assisting in ensuring a true and complete corporate governance effectiveness in an organization. Going by the words of Crumbley (2007):Forensic accounting is the accounting that is appropriate for legal review, offering the highest level of assurance, and been arrived at in a scientific fashion. That is forensic accounting is sufficiently thorough and complete so that an accountant, in his/her considered independent professional judgment, can deliver a finding, as to the accounts, inventories, or the presentation thereof that is of such quality that it would be sustainable in some adversarial legal proceeding, or within some judicial or administrative review.As a forerunner to the above view, Manning (2002) also defines forensic accounting as “the application of financial accounting and investigative skills to a standard acceptable by the courts to address issues in dispute in the context of civil and criminal litigation".While this study agrees that financial scandals in business organisation have raised the awareness that accountants should be alert to potential fraud and other illegal activities while performing their duties, they can also be made to provide significant assistance in preventing, investigating and resolving such issues. Forensic accounting is another aspect of accounting which tends to further highlight the natural relationship existing between accounting and law just as auditing.

1.1. Concept of Forensic Auditing

- Forensic auditing is the integration of accounting, auditing and investigative skills (Zysman, 2004). Dhar and Sarkar (2010) define forensic auditing as the application of accounting concepts and techniques to legal problems. It demands reporting, where accountability of the fraud is established and the report is considered as evidence in the court of law or in administrative proceedings.Degboro and Olofinsola (2007) note that forensic investigation is about the determination and establishment of fact in support of legal case. That is, to use forensic techniques to detect and investigate a crime is to expose all its attending features and identify the culprits. In the view of Howard and Sheetz (2006), forensic auditing is the process of interpreting, summarizing and presenting complex financial issues clearly, succinctly and factually often in a court of law as an expert. It is concerned with the use of accounting discipline to help determine issues of facts in business litigation (Okunbor and Obaretin, 2010).Forensic auditing is a discipline that has its own models and methodologies of investigative procedures that search for assurance, attestation and advisory perspective to produce legal evidence. It is concerned with the evidentiary nature of accounting data, and as a practical field concerned with accounting fraud and forensic auditing; compliance, due diligence and risk assessment; detection of financial misrepresentation and financial statement fraud (Skousen and Wright, 2008); tax evasion; bankruptcy and valuation studies; violation of accounting regulation (Dhar and Sarkar, 2010).Curtis (2008) argues that fraud can be subjected to forensic auditing, since fraud encompasses the acquisition of property or economic advantage by means of deception, through either a misrepresentation or concealment.Bhasin (2007) notes that the objectives of forensic auditing include: assessment of damages caused by an auditor’s negligence, fact finding to see whether an embezzlement has taken place, in what amount, and whether criminal proceedings are to be initiated; collection of evidence in a criminal proceedings; and computation of asset values in a divorce proceedings.He argues that the primary orientation of forensic auditing is explanatory analysis (cause and effect) of phenomenon- including discovery of deception (if any), and its effects-introduced into the accounting domain.According to Bhasin (2007), forensic auditors are trained to look beyond the numbers and deal with the business realities of situations. Analysis, interpretation, summarization and the presentation of complex financial business related issues are prominent features of the profession. He further reported that the activities of forensic auditors involve: investigating and analyzing financial evidence; developing computerized applications to assists in the analysis and presentation of financial evidence; communicating their findings in the form of reports, exhibits and collections of documents; and assisting in legal proceedings, including testifying in courts as an expert witness and preparing visual aids to support trial evidence.

1.2. Financial Fraud

- Financial fraud has been variously described in literature. No one description suffices. Wikipedia dictionary describes Fraud as crimes against property, involving the unlawful conversion of property belonging to another to one’s own. Williams (2005) incorporates corruptions to his description of financial crimes. Other components of fraud cited in Williams (2005) description include bribes, cronyism, nepotism, political donation, kickbacks, artificial pricing and frauds of all kinds. The array of components of financial crimes, some of which are highlighted above, is not exhaustive.The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) Act (2004) attempts to capture the variety of economic and financial crimes found either within or outside the organization. The salient issues in EFCC Act (2004) definition include “violent, criminal and illicit activities committed with the objective of earning wealth illegally… in a manner that violates existing legislation… and these include any form of fraud, narcotic drug, trafficking, money laundering, embezzlement, bribery, looting and any form of corrupt malpractices and child labour, illegal oil bunkering and illegal mining, tax evasion, foreign exchange malpractice including counterfeiting, currency, theft of intellectual property and piracy, open market abuse, dumping of toxic waste and prohibited goods, etc. This definition is all-embracing and conceivably includes financial crimes in corporate organization and those discussed by provision authors (William, 2005 and Khan, 2005). At the level of corporate organizations, financial crimes were known to have led to the collapse of such organizations.Cotton (2003) attributes the collapse of Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, Adelphia, to corporate fraud. $460 billion was said to have been lost. In Nigeria, Cadbury Nig. Plc whose books were criminally manipulated by management was credited to have lost 15 billion Naira. In the case of the nine collapsed commercial banks in Nigeria, about one trillion naira was reported to have been lost through different financial malpractice. This is still being investigated by EFCC under the EFCC Act (2004). Generally, financial fraud is varied and committed by individuals and institutions.Karwai (2002) and Ajie and Ezi (2000) are of the view that financial fraud in organizations vary widely in nature, character and method of operation in general. Fraud may be classified into two broad ways: nature of fraudsters and method employed in carrying out the fraud. On the basis of the nature of the fraudsters, fraud may be categorized into three groups, namely; internal, external and mixed frauds. Internal fraud relates to those committed by members of staff and directors of the organizations while external fraud is committed by persons not connected with the organization and mixed fraud involves outsiders colluding with the staff and directors of the organization. Karwai (2002) reported that the identification of the causes of fraud is very difficult. He stated that modern day organizations frauds usually involve a complex web of conspiracy and deception that often mask the actual cause. Ajie and Ezi (2000) are of the view that studies have shown that on the average out of every 10 staff would look for ways to steal if given the opportunity and thus only 4 could be normally honest.

1.3. Challenges of Forensic Auditing Application in Nigeria

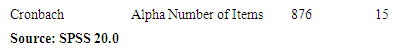

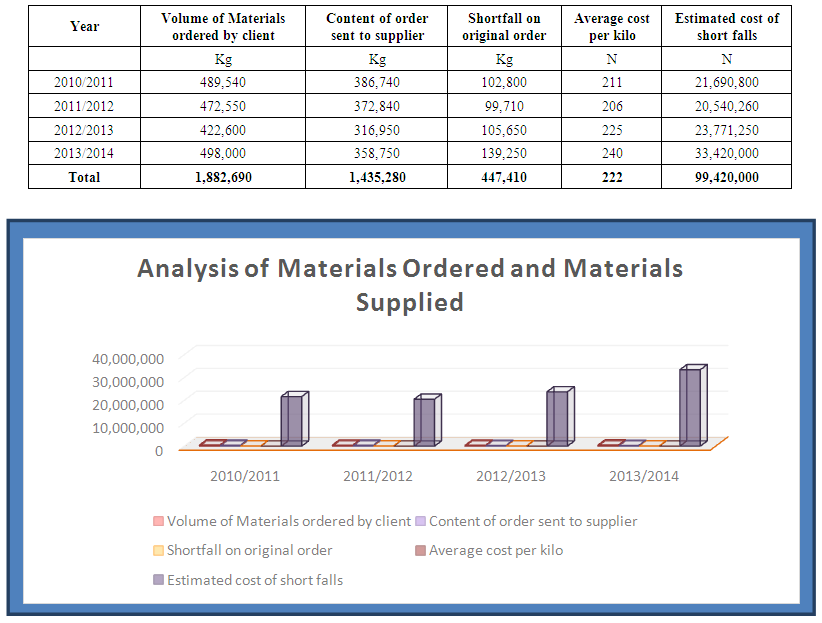

- With an upsurge in financial accounting fraud in the current economic scenario experienced, financial accounting fraud detection (FAFD) has become an emerging topic of great importance for academia and real sector.The failure of internal auditing system of the organization in identifying the accounting frauds has led to use of specialized procedures to detect financial accounting fraud, collectively known as forensic auditing (Sharma and Panigrahi 2012).Though financial fraud in Nigeria has witnessed highly publicized cases especially in the banking system, Enyi (2009) undertook a study to offer suggestions using real case problem on how to apply forensic auditing in investigating variances and suspected fraudulent activities in manufacturing processes and thus suggests that the application of forensic auditing applies to all scenes where fraud is a possibility.Okoye and Akenbor (2009) commenting on the application of forensic auditing in developing economies like Nigeria, notes that forensic auditing is faced with so many bottlenecks. Crumbley (2007), Grippo and Ibex (2003) reveal the following challenges confronting the application of forensic auditing. (i) A significant challenge that faces a forensic auditors is the task of gathering information that is admissible in a court of law.(ii) The admissibility, of evidence in compliance with the laws of evidence is crucial to successful prosecutions of criminal and civil claims. (iii) Globalization of the economy and the fact that a fraudster can be based anywhere in the world has led to the problem of inter-jurisdiction.Degboro and Olofinsola (2007) note that an important challenge to the application of forensic auditing in financial fraud control in Nigeria is that the law is not always up to date with the latest advancements in technology. Also, forensic auditing is seen as an expensive service that only big companies can afford. Thus, most companies prefer to settle the issue outside the court to avoid the expensive cost and the risk of bad publicity on their corporate image. In addition, forensic auditing is a new trend particularly in developing economies.Hence, auditors/accountants with adequate technical know-how on forensic issues are hardly available.Hypotheses1. There is no significant agreement on the effectiveness of forensic auditing in financial fraud control.2. There is no significant agreement on the effectiveness of forensic auditing in improving financial reporting quality.3. Forensic auditing is not effective in improving internal controls

2. Problem Statement

- Investigative audit has always been there, it is only the techniques involved that has been changing in line with sophistication of the financial fraud involved (Krancher, 2006). What is necessary at this juncture is the need to stress that all normal statutory audit should contain some element of forensic enquiry. After all, evidence of fraud or fraudulent activities can easily be sniffed if a thorough evaluation of the adequacy and compliance of the internal control mechanism is made.In addition, extensive analysis of variances from operational data can also help to point out areas that need proper/deeper analytical investigation. Fraud emanating from operational controls especially in a manufacturing out fit or construction firms are much more difficult to detect than prevent. This is because stock and working materials are more the subject of theft here than cash or other form of expendable/portable resources. Most organisations can prevent such frauds effectively with the use of a good security apparatus. However, in an environment where security men are known to have strong collaborations with officials who pilfer organisational materials and sometimes with robbers outside the organisation, there still exist high probability for fraudulent activities even with such high level of security. Asein 2007), in his comments on the provisions of the recently issued international Standard on Auditing No. 240 (ISA240) which has its local equivalence in the Nigerian Standard on Auditing No.5 (NSA5), stated that sampling as an audit technique will no longer suffice. The ISA 240, in like manner, requires the auditor to identify and assess the risks of material misstatements due to fraud at financial statement level. And for those assessed risks that could result in a material misstatement due to fraud, he should evaluate the design of the entity's related controls, including relevant control activities, and to determine whether they have been implemented. The implication of the above as stated by Asein (2007) is that it is now the responsibility of the auditor not only to prevent but also to detect fraud. This of course, now necessitates treating every audit exercise as a fresh assignment and disregarding any previous confidence on the integrity of the management.Furthermore, Ojaide (2000) submits that there is an alarming increase in the number of fraud and fraudulent activities in Nigeria emphasizing the visibility of forensic auditing services. Okoye and Akamobi (2009) Owojori and Asaolu (2009), Izedomin and Mgbame (2011), Kasum (2009) have all acknowledge in their separate works, the increasing incidence of fraud and fraudulent activities in Nigeria and these studies have argued that in Nigeria, financial fraud is gradually becoming a normal way of life. As Kasum (2009) notes, the perpetuation of financial irregularities are becoming the specialty of both private and public sector in Nigeria as individual perpetrates fraud and corrupt practice according to the capacity of their office. Consequently, there is a general expectation that forensic auditing may be able to stem the tide of financial malfeasance witnessed in most sectors of the Nigerian economy. However, there has not been adequate emphasis, especially survey evidence on how forensic auditing can help curb financial crimes beyond the several anecdotal views that abound. Consequently, the paper fills this gap by addressing the following research questions;- Is there significant agreement on the effectiveness of forensic auditing in financial fraud control?- Is there significant agreement on the effectiveness of forensic auditing in improving financial reporting quality?- Is forensic auditing effective in improving internal controls?

3. Objective of the Paper

- In view of the foregoing, the objective of this paper is to highlight other methods and procedures that can be adopted in investigating variances and suspected fraudulent activities concealed in a financial statement in line with the requirements of ISA 124 in a manufacturing environment using the empirical and experimental approaches to forensic investigation. This paper was based on the forensic investigation carried out on the activities of a chemical manufacturing company located at Onitsha, Anambra State, Nigeria between the period 1st June 2014 and 12th August 2014.

4. Methodology

- The investigation which began as a normal year end audit, at first, took the form of an empirical review comparing the accounts presented for auditing for the year ended 31st March 2014 with that of the previous year as well as the budgeted figures for the same year. As usual, the nominal audit plan was mapped out to produce the audit programme which was followed and modified in process as the needs arise. The comparative analysis with the previous year showed some seeming consistency, while a variance analysis performed on the budgeted figures using standard estimates of material mix and yield formulae revealed differences that put the study on further enquiry. This became the basis for conducting production experiments as narrated below.With the permission of the company’s chief executive officer, the production manager was asked to make 5 production runs of equal material measurements using the budgeted standard figures under the close observation of the researcher. This was carried out with stunning but consistent results. The researcher asked for the sixth production run using the double of the materials used for each of the first five. The result also gave expected volume of output.

4.1. Results from Experimental Productions

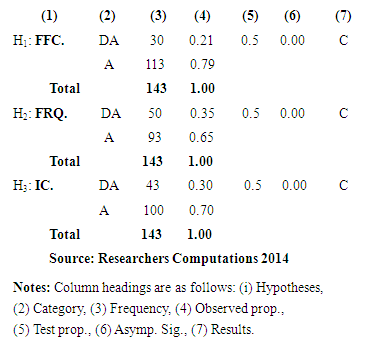

- As stated earlier, the results from the 5 test runs of equal material measurements gave almost the same volume of output while that of the sixth run gave the double of the output from the average of the five outputs. The observation is tabulated as Table 1.

| Table 1. Experimental Production Trial Results |

4.2. Issues from the Experimental Results

- The almost 100% consistency of outputs from inputs confirmed our initial hunch on the likelihood of fraud when the comparative analysis was done because the variances from the analysis were huge and adverse in contrast with our experimental findings. The analysis of the company's records revealed that a total of 497,952 kiloqrams of materials were used to get a total of 75,481 sheets of foam products as against the expected output of 104,832 sheets. This invariably means that either 29,351 finished products or 139,417.25 kilograms of materials cannot be accounted for. If this is so, then what happened?To answer the above question in the context of our investigation, we need to address the following issues:a) Were there production damages during the accounting period?b) Were the stock issuance records correctly entered? c) Were the goods received notes correctly entered? d) Were the records of outputs correctly stated in the production inputs log book? e) Were the records of outputs correctly stated in the production outputs log book?f) Were the goods received notes correctly checked against supplies on arrival at the security post?g) Were there stock returns to suppliers?h) Were there criminal collaborations between the production, stores and the security?i) Is it possible to have fictitious transactions?

4.3. Addressing the Issues Raised

- Some of the issues raised above were put as audit queries to the concerned officials while the researcher embarked on forensic audit to resolve the issues on production damages, criminal collaborations and fictitious transactions.On the issue of production damages, a thorough analysis of the production and maintenance log books was carried out and there was no evidence to support the assertion that there is either a machine breakdown or that there were production damages that could have accounted for all or some of the adverse production volume variance of 29,351 sheets of foam during the period. This hint became the first confirmation that something suspicious has been going on all along. For how long? At what magnitude? With what style? These are further questions we must find answer to before we can arrive at a conclusion meaningful enough to serve as a forensic accounting investigations report.After studying the various replies to our audit queries on the issues bordering on stock recording, security checks, issuance to input stocks and receipts of both finished goods from production and raw materials from the suppliers, the next attempt must naturally be to establish criminal collaboration between the suspects. This became a herculean task that seemed unattainable at first, as most of our verbal enquiries were simply rebuffed and or dismissed by both the management and other operational staff. However, these negative attitudes towards our efforts could not deter us because we already had a lead and we were ever determined to follow this lead to the end. In any case and as strong as our suspicions were, we had concluded beforehand that it will be impossible to establish criminal collaboration unless we are able to establish a proof that there were fictitious transactions.The first clue that pointed towards the suggestion of the existence of fictitious transactions was spotted during the analysis of the yearly comparative figures. While the reported financial data seemed to follow the same pattern for the last four years, the variance analysis of input/output relationship fluctuated between 20% and 30% within the same periods without any significant justification. Now, if profit elements seemed to follow the same pattern while budgets differ only in production outputs from the recorded actual performance, should it be feasible to rely on the assumed “credibility” of the financial reports presented by the directors through the Chief Accountant? Not likely. Something seems to be wrong somewhere and that is what we must investigate.To further confirm our suspicion or to confound it on the other hand we subjected the reported profits for a period of four years to another comparative analysis using the periods projected figures adjusted for the volume of production inputs used. The differences obtained from this analysis were further subjected to price change analysis for both inputs and resultant outputs using the standard projected data as base figures and adjusting up or down as the case may be. This exercise facilitated the translation of all transaction data into a common measurement unit for all the periods under the comparative analysis.The result revealed adverse variances which ranged between 21.5% and 30.6% for the 4 years period, just almost the same pattern with the results of the variance analysis of input output relationship as aforementioned. A careful study of the financial statements for the four years to 2014 showed that the management of the company has been very meticulous about their finances, hence, no trace of physical financial leakage was found. The only possible way through which any fraud could have been perpetrated would be on materials handling; and this can only happen either in the form of input stock diversion or output stock pilferage. However, the output stock control system in place and which we have tested and found to be highly effective made the option of output stock theft unviable. Thus, the only option left was to investigate the possibility of input stock pilferage of diversion.

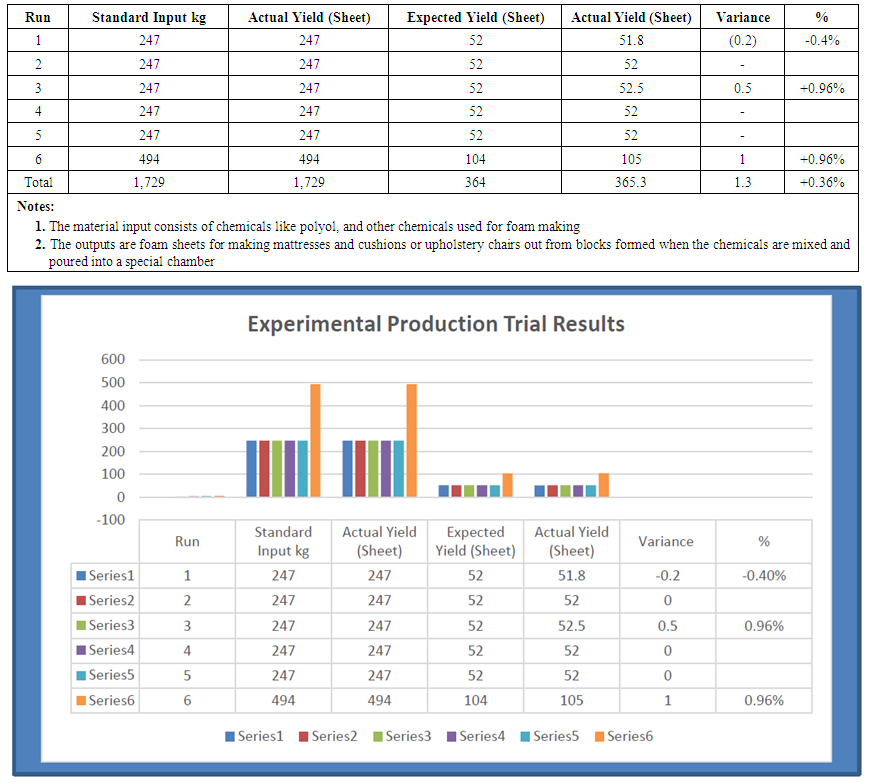

4.4. Investigating Input Chains

- To enhance the credibility and ease of flow of the input stock investigation as decided, we modified our programme to include a visit to each of the origin of the various stock items in the into investigation schedule. The company uses three main suppliers of raw materials but these suppliers deliver goods to the company vehicles only at the suppliers’ own warehouses. This is an arrangement agreed to between our client and one other company which acts as a central procurement company for all members of the group which our client belongs. Since the suppliers and the procurement company are external to the company, we need to obtain special permission from their management through the management of our client company to enable us extract data relating to our client from their records. The aim of this exercise is simply to obtain stock purchased data with which to compare with the stock received data as recorded by the security department and stock records and books at our client's factory premises. This was done and the exercise turned out to be the master stroke as it revealed so many discrepancies between what were purportedly ordered and what were eventually supplied.The analysis of findings from this exercise is as tabulated in Table 2. Few questions thrown at the Chief Buyer on the discrepancies revealed that the discrepancies were meticulously planned, skillfully executed and carefully concealed.

| Table 2. Analysis of Materials Ordered and Materials Supplied |

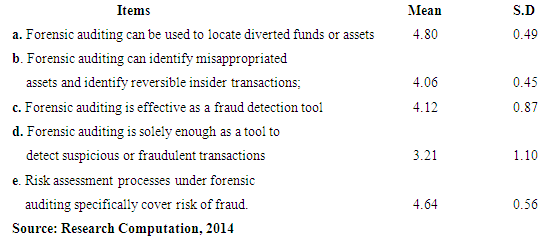

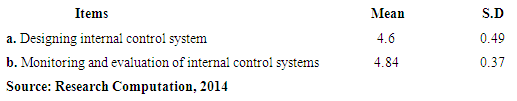

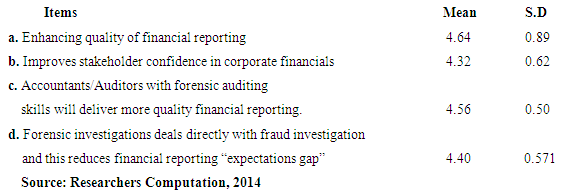

5. Presentation of Results

- Figure 1 Sex Distribution of the respondentsSource: Researchers survey, 2014.From the analysis of the responses retrieved, of the 143 respondents whose responses were used for the analysis, 80 of the respondents were female which represents 55.9% of the sample while 63 of the respondents were males which represent 45.1% of the sample.Figure 2 Age Distribution of the respondentsSource: Research Survey, 2014.From the analysis of the responses retrieved, of the 143 persons whose responses were used for the analysis, 28(19.58%) of the respondents were within the age range of 20-30 while 62(43.4%) of the respondents were in the age range of 31-40 years. Furthermore, 30 (20.97%) of the respondents were in the age range of 41-50 while 23(16.08%) were in the range 51-above.Figure 3 Educational Qualification of the respondentsSource: Research Survey, 2014From the analysis of the responses retrieved, of the 143 students whose responses were used for the analysis, 53(37.06%) of the respondents have M.sc qualifications. 67(46.85%) of the respondents have B.SC/H.ND qualifications while 23(16.08%) of the respondents had the Ordinary National Diploma (O.N.D)Figure 4. Employment status of the respondentsSource: Research Survey, 2014From the analysis of the responses retrieved, of the 143 students whose responses were used for the analysis, 35(24.48%) of the respondents are self-employed while 64(44.76%) of the respondents work in public organisations. Furthermore, 51 (35.66%) of the respondents work in private institutions.

|

|

|

|

6. Discussions

- The difference between forensic investigations and normal auditing is that the former must look beyond the figures in the financial records and deal directly with the business reality of the situation at hand. In the opinion of Zysman (2007), the specialty known as forensic accounting was formed by integrating accounting, auditing and other investigative skills, which is capable of providing an accounting analysis that is suitable to the court for the purpose of dispute resolution. It encompasses both litigation support and investigative accounting. In order to fully comprehend the role of forensic accounting the Encarta Dictionary further defines it as “auditing to find fraud” and “auditing practice carried out to detect possible criminal activity concealed in financial accounts”. Forensic accounting investigation exercises can be very tasking but at the same time very interesting for a discerning investigator. The direction and depth of investigation will depend first on the outcome of the preliminary and other connected intermediate investigations as well as largely on the personal intuition of the investigators. No one method may seem perfect as well as different approaches especially when circumstance, environment and place of incidence under scrutiny differ as they always do in most cases. The various techniques applied so far for the case under contemplation were not stereotyped as it is usual with normal statutory audits; hence this approach tends to supports the above view. Going by the words of Zysman (2007) as quoted earlier, we have been able to apply a combination of simple auditing techniques of internal control evaluation tests on randomly selected significant transactions. Simple accounting ratio analysis and simple variance analysis used in cost accounting to arrive at clues had pointed out the true direction that our investigation must follow to be able to uncover the sense of criminal activities that were concealed on incremental basis over the past four years in the company's financial statements. The instance of forensic investigation as highlighted above was able to provide an accounting analysis that almost revealed the whole extent to which fraudulent activities in the buying and production division affected the company's fortunes over the stated periods. The main points of the analysis became the main evidence with which the police was able to arrest and prosecute the perpetrators of the fraud the outcome of which was an out of court settlement between the company and those accused.

7. Conclusions

- Fraud and official corruption globally have taken monumental strides and so also have efforts to curb them. Forensic investigations and accounting as seen from the curriculum of the few institutions offering them as a course or part of a course have been mostly characterised by investigations into money laundering cases, tracking of illegal money flow, detection of financial frauds in financial institutions, prevention of insider abuse and many more.Less emphasis has been laid on the detection and prevention of operational process frauds such as sometimes witnessed within a manufacturing environment. The urge to make extra money and get rich at all costs has rendered the word "trust" almost meaningless in some circles. Applying forensic methods in the investigation of manufacturing process frauds may not follow a single direction but must include some or all of the elements of the following procedure to succeed:a) Apply the normal audit approach to obtain preliminary indications that further/detailed investigation is necessary.b) Make detailed and varied analyses (financial, materials, assets, personnel, etc.) on areas where exceptions seem to exist. This can best be done using a combination of normal audit tests and management accounting techniques particularly variance analysis.c) Obtain the permissions needed to extend your investigation when it is reasonable to conclude that you have been put on enquiry’. You are put on enquiry when you seem to notice a suspicious transaction or trend or extra-ordinary event that is out of budgetary limitations or that has never occurred before.d) Investigate the origin, manner and effects of the suspicious item on the affairs, movement or behaviour of the resultant events, effects or actions (cause and effect relationship).e) Make necessary enquiries (in most cases using audit query style for full documentation of the answers) on areas where explanation of those incharge of the process is required for enquiries outside the four walls of the entity, obtain the required permission and necessary letter of introduction to visit the offices/premises of the third parties concerned. g) Document your findings and the supporting evidence and make the necessary report to the appropriate authority.As can be learned from the methodology adopted for this investigation, a number of techniques were used, first was the comparative analysis between prior and present financial year, then followed by the variance analysis between the budgeted standards and the attained levels. This produced the first major clue that put our team on enquiry due to the exceptional nature of the variances. This then led us to experiment with the production process in order to find out whether the variances were caused by damages or production inefficiency. The answers from these experiments were negative and that made our investigation to look out for other possible cause(s) of the huge variance, hence, our probe into the material procurement machinery.In summary, forensic accounting as a discipline is an interesting one and can be highly rewarding to both the society and the investigator. However, it is pertinent to note here that only persons of impeccable character and capable of resisting temptation at any level that can be successful in the process of forensic investigation. And that financial Fraud is real and has become prevalent in contemporary business environment. This trend needs to be arrested before it is too late. Forensic auditing is the new branch of accounting which has the sole aim of unearthing fraudulent activities within and outside an organization so far as the third party’s action is in any way reflective on the activities of that organization.This paper also found that there is significant agreement amongst stakeholders on the effectiveness of forensic auditing in fraud control, improving financial reporting and internal control. Accountants should therefore be alert to potential fraud and other illegal activities while performing their duties. They can also be made to provide significant assistance in preventing, investigating and resolving such issues. In line with the above findings, we recommend that the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nigeria, Association of National Accountants of Nigeria and the National Universities Commission should encourage formalization and specialization in the field forensic accounting. In addition, the government should develop interest in forensic auditing for monitoring and investigation of suspected corruption cases.

References

| [1] | Adeniyi, A.A. (2004), Auditing and Investigation. Value Analysis Consult, Lagos. |

| [2] | Ajie, H.A. and C.T. Ezi, (2000): Financial Institutions and Markets. Corporate Impressions, Owerri. |

| [3] | Alvin, A.S. & James, K.L. (1984), Auditing and Investigation Approach. Longman Group Limited, London. |

| [4] | Apostolou, B., Hassell, J.M., and S.A. Webber (2000): “Forensic Expert Classification of Management Fraud Risk Factors, Journal of Forensic Accounting. Vol.I (181-192). |

| [5] | Apostolou, N.G. & Crumbley, D.L. (2006), Forensic Investigations: Red Flogs, Retrieved September 4,2007 from http:/Iwww.bus.lsu.edu/accounting/faculty/napostolou |

| [6] | Arens, A.A.; Elder, R.J. & Beasley, M.S. (2006), Auditing and Assurance Services - An Integrated Approach (Eleventh Ed.) New Jersey: Prentice Hall. |

| [7] | Asein, A.A. (2007), “Auditors’ Changing Responsibilities", the Nigerian Accountant, Vol. 40(3), Lagos: Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nigeria. |

| [8] | Bhasin, M.L. (2007), Forensic Accounting and Auditing – Perspectives and Prospects, Accounting world magazine, http://www.iupindia.in/107/AW_Forensic_Accounting_Auditing_40.html |

| [9] | Clive de Paula, F. and Attwood, F.A. (1983), Auditing Principles and Practice. Sixteenth Edition, Pitman Books Limited, London. |

| [10] | Cotton, M.P. (2003). Corporate Fraud Prevention, Detection and Investigation: A Practical Guide of Dealing with Corporate Fraud, Australia: Price Water House Coopers |

| [11] | Crumbley, D.L. (2007), Journal of Forensic Accounting, Retrieved April 11, 2008 from http://www.allbusiness.com Accounting, reporting/forensic-amounting/900680-1. |

| [12] | Curtis, G.E., (2008) Legal and Regulatory Environments and Ethics: Essential Components of Fraud and Forensic Accounting Curriculum. Issues Account. Educ. 23(4): 535-543. |

| [13] | Degboro, D. and J. Olofinsola, 2007. Forensic Accountants and the Litigation Support Engagement. Nigeria Accountant. 40(2): 49-52. |

| [14] | Dhar, P. and A. Sarkar, 2010. Forensic Accounting: An Accountant’s Vision. Vidyasagar University of Commerce, 15(3): 93-104 |

| [15] | Hawlard, R. (1982), Auditing Seventh Edition, Macdonald and Evans Limited, London. |

| [16] | Howard S. and Sheetz, M. (2006): Forensic Accounting and Fraud Investigation for Non- Experts, New Jersey, John Wiley and Sons Inc. |

| [17] | International Standard on Auditing No: 240 (ISA 240). |

| [18] | Izedomin F.I and Mgbame C.O. (2011): Curbing Financial Frauds in Nigeria, A Case for Forensic Accounting. African journal of humanities and society. No 1, vol 12 pp 52-56. |

| [19] | Karwai, M. (2002). Forensic Accounting and Fraud Investigation for Non-Expert, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. |

| [20] | Kasum, A.S (2009): The Relevance of Forensic Accounting to Financial Crimes in Private and Public Sectors of Third World Economies: A Study from Nigeria Proceedings of The 1st International Conference on Governance Fraud Ethics and Social Responsibility, June 11-13, 2009. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract =1384242. |

| [21] | Krancher, M. (2006), Forensic Accounting As An Investigative Tool, CPA Journal. Retrieved December 18, 2007 from http://www.nysscpa.orgIcpajoumal/20061806. |

| [22] | Manning, A. (2007), Financial Investigation and Forensic Accounting, USA CRC Press. |

| [23] | Millichamp, A.H. (2002), Auditing. Eight Edition, Continuum Tower Building, New York. |

| [24] | Nwaze, C. (2008), “Fraud and Anti-fraud Challenges In Contemporary Nigerian Banking", Zenith Economic Quarter. Vol. 3(1), Lagos: Zenith Bank Plc. |

| [25] | Ojaide, F. (2000): Frauds Detection and Prevention: The Case of Pension Accounts. ICAN NEWS January/March. P8. |

| [26] | Okolo, J.U.T. (2001), The Concept and Practice of Auditing. Evans Brothers Nigeria Limited, Ibadan. |

| [27] | Okoye E.I and Akamobi N.L (2009): The Role of Forensic Accounting in Fraud Investigation and Litigation Support. The Nigerian Academic Forum Vol 17 No1. |

| [28] | Okunbor. J.A and Obaretin. O (2010): Effectiveness of the Application of Forensic Accounting Services in Nigerian Corporate Organisations. AAU JMS Vol. 1(1). |

| [29] | Owojori, A.A and Asaolu T. O. (2009): The Role of Forensic Accounting in Solving the Vexed Problem of Corporate World. European Journal of Scientific Research Vol.29 No.2 (2009), pp.183-187. |

| [30] | Pratt, M.J (1982), Auditing Longman Group Limited, London. |

| [31] | Santock, J. (1978), Case Studies in Auditing. Second Edition, Macdonald and Evans Limited, London. |

| [32] | Williams, I. (2005) “Corrupt Practices: Implications for Economic Growth and Development of Nigeria”, The Nigeria Accountants, 38 (4), pp 44-50. |

| [33] | Zysman, A. (2007), Forensic Accounting Demystified, Forensic Accounting and Litigation Support, Retrieved April 11, 2008 from http:/lwwwforensicaccounting.comlon |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML