| [1] | Acs, Z. J., & Plummer, L. A. (2005). Penetrating the 'knowledge filter' in regional economies. The Annals of regional Science, Vol 39, 439-456. |

| [2] | Anand, B. a. (2000). "Do Firm Learn to Create Value? The Case of Alliances". Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 295-315. |

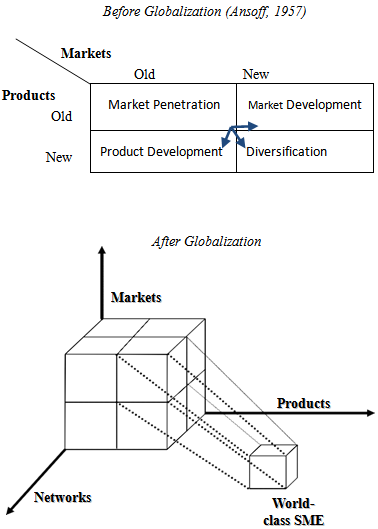

| [3] | Ansoff, H. (1957). "Strategies for diversification". Harvard Business Review , 35, 113-124. |

| [4] | Antoncic, B. a. (2001). "Intrapreneurship: construct refinement and cross-cultural validation". Journal of Business Venturing, 16, 495-527. |

| [5] | Armitage, J. W., Brook, N. A., Carlen, M. C., & Shulz, S. P. (2006). Remodeling Leadership. Performance Improvement, Vol 45, Issue 2, Pp 40-51. |

| [6] | Babbie, E. a. (2003). "The practice of social research" (South African Edition ed.). Cape Town: Oxford University Press. |

| [7] | Barney, J. B. (1995). Looking inside for competitive advantage. Academy of Management Executive, Vol 9, No.4, pp 48-61. |

| [8] | Baum, J. a. (1991). "Institutional linkages and organizational mortality". Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, pp. 187-218. |

| [9] | Baum, J. C. (2000). "Don't Go it Alone: Alliances Network Composition and Start-up's Performance in Canadian Biotechnology". Strategic Management Journal, 21, 267-294. |

| [10] | Bearden, W. a. (1999). "Handbook of Marketing Scales: Multi-item measures for Marketing and Consumer Behaviour" (2nd Edition ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. |

| [11] | Beaver, G. (2007). The strategy pay-off for smaller enterprises. 28(1, pp 11-17). |

| [12] | Berte, E., Rodrigues, L. C., & Ameida, M. I. (2010). The Lessons Learned from the Unique Characteristics of Small technology-based Firms. 6(1). |

| [13] | Beyene, A. (2002). "Enhancing the Competitiveness and Productivity of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (SMEs) in Africa: An Analysis of Differential Roles of National Governments Through Improved Support Services". Africa Development, XXVII(3), 130-156. |

| [14] | Borgelt, K., & Falk, I. (2007). The leadership/Management conundrum: innovation or Risk Management? Leadership and Organisation Development Journal, Vol 28, No. 2, pp 122-136. |

| [15] | Bradley, F. M. (2006). "Use of supplier-customer relationship by SMEs to enter foreign markets". Industrial Marketing Management, 35, 652-665. |

| [16] | Brockhaus, R. (1980). "Risk taking propensity of entrepreneurs". Academy of Management Journal, 23(3), 509-520. |

| [17] | Brown, S. L., & Eisenhardt., K. (1997). The Art of Continuous Change: Linking Complexity Theory and Time paced evolution in Relentlessly shifting Organisations. Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol 42, 1-34. |

| [18] | Carland, J. H. (1984). "Differentiating entrepreneurs from small business owners: A conceptualization". Academy of Management review, 9(2), 349-354. |

| [19] | Christensen, C. a. (2000). Meeting the Challenge of Disruptive Change. Harvard Business Review, March-April, pp 67-76. |

| [20] | Cohen, W. a. (1990). "Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation". Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, pp. 128-152. |

| [21] | Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol 35, 128-152. |

| [22] | Cooper, D. a. (2006). "Marketing research". New York: McGraw-Hill. |

| [23] | Covin, J. a. (1989). "Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments". Strategic Management Journal, 10, 75-87. |

| [24] | Cozby, P. (2004). "Methods in behavioural research" (5th Edition ed.). Moutain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company. |

| [25] | Day, G. S. (1994). The Capabilities of Market Driven Organisations. Journal of Marketing, Vol 58, pp 37-52. |

| [26] | Dean, J. J. (1996). "The strategic use of integrated manufacturing: an empirical examination". Strategic Management Journal, Vol.17, No.6, 459-480. |

| [27] | Dijkstra, T. (1983). "Some comments on maximun likelihood and partial least squares methods". Journal of Econometrics, 22, 67-90. |

| [28] | Dijkstra, T. (1985). "Latent variables in linear stochastic models: Reflection on maximum likelihood and partial least squares methods" (2nd Edition ed.). Amsterdam: Sociometric Research Foundation. |

| [29] | Dillman. D.A and Dillman, D. (2000). "Structural determinats of mail survey response rates over a 12 year period, 1988-1999". Retrieved May 8, 2009, from http://www.amstat.org/sections/SRMS/Proceedings/papers/2000. |

| [30] | Ebers, M. a. (1998). "The construction, forms, and consequences of industry networks". International Studies of Management Organization, 3-21. |

| [31] | Efron, B. a. (1993). "An introduction to the boostrap: Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability". New York: Chapman & Hall. |

| [32] | Evanschitsky, H., Ahlert, D., Blaich, G., & Kenning., P. (2007). Knowledge Management in knowledge intensive service networks. Management Decisions, Vol 45, No. 2, pp 265-283. |

| [33] | Fornell, C. a. (1981). "Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error". Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39-50. |

| [34] | Fornell, C. a. (1982). "Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory". Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 440-452. |

| [35] | Freel, M. (2000). "Strategy and structure in innovative manufacturing SMEs: the case of an English region". Small Business Economics, 15, 27-45. |

| [36] | Galuni DC, E. K. (1994). Renewing the Strategy-Structure Performance Paradigm. In S. B. (eds), Research in Organisational Behaviour (pp. 215-55). Greenwich CT: JAI Press. |

| [37] | Gelinas, R., & Bigras, Y. (2004). The Characteristics and Features of SME's: Favourable or Unfavourable to Logistics Integration. 42(3, pp 263-278). |

| [38] | Goleman, D. (2002). "Business: The ultimate resource". London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. |

| [39] | Gulati, R. (1998). "Alliances and networks". Strategic Management Journal, Vol.19, 293-317. |

| [40] | Gulati, R. N. (2000). "Strategic networks" . Management Journal, 21, 203-216. |

| [41] | Hagedoorn, J. R. (2006). "Inter-Firms R&D Networks: The importance of Strategic Network Capabilities for High-Tech Partnership Formation". British Journal of Management, 17, 39-53. |

| [42] | Hair, J. B. (2000). "Marketing Research: A practical approach for the new millennium". Boston: McGraw-Hill International. |

| [43] | Hair, J. B. (2006). "Multivariate data analysis" (6th Edition ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. |

| [44] | Hakansson, J. a. (1994). "The effect of strategic technology alliance on company performance". Strategic Management Journal, 15, 291-310. |

| [45] | Hanna, V. a. (2002). "Small firm networks: a successfull approach to innovation?". R&D Management, 32(3), 201-207. |

| [46] | Harrison, A. (1998). "Manufacturing strategy and the concept of world-class manufacturing". International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 18(4), 397-408. |

| [47] | Haynes, P.,. (1998). "Small and mid-sized businesses and Internet use: unrealised potential?". Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 8(3), 229-235. |

| [48] | Heriot, K. C., & Loughman, T. P. (2009). Resolving the Planning Conundrum in New Venture Creation: An adaptation of Mintzberg's formation perspective. 14(4). |

| [49] | Hills, G. a. (1992). "Research at the marketing interface to advance entrepreneurship theory". Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(3), 33-59. |

| [50] | Hoang, H. a. (2003). "Network-based research in entrepreneurship: a critical review". Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 165-187. |

| [51] | Hutt, K., Gavieres, R., & Chakraborty, B. (2007). Limited-potential niche or prospective market foothold? Five tests. 35(4, pp 18-22). |

| [52] | Julien, P. a. (2001). "Dynamic regions and high growth SMEs: uncertainty, potential information and weak signal networks". Human Systems Management, Vol.20, 237-248. |

| [53] | Kale, P. D. (2002). "Alliance capability, stock market response, and long-term alliance success: the role of the alliance function". Strategic Management Journal, 23, 747-767. |

| [54] | Kalwani, M. a. (1995, January). "Long-term manufacturer-supplier relationships: Do they pay off for supplier firms?". Journal of Marketing, 59, 1-16. |

| [55] | Kotey, B. a. (1997). "Relationships among owner/manager personal values, business strategies, and enterprise perfomance". Journal of Small Business Management, April, 37-64. |

| [56] | Koufteros, X. V. (2002). "Integrated product developement practices and competitive capabilities: the effects of uncertainty, equivocality, and platform strategy". Journal of Operations Management, 20, 331-355. |

| [57] | Kreiser, P. M. (2002). "Assessing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, the external environment and firm performance". Retrieved May 12, 2009, from http://www.babson.edu/entrep/fer/Babson2002/XVII/XVII_S4/SVII_S4_nav.html. |

| [58] | Lahiri, D. (2011). A framework to identify the internal attributes that predict the 'high performance potential' in micro enterprises. Maastricht: MPhil Research @ Maastricht School of Management. |

| [59] | Lee, D. a. (1998). "The role of relational exchange between exporters and importers: evidence from small and medium-sized Australian exporters". Journal of Small Business Management, 36(4), 12-23. |

| [60] | Lefebre, L. L. (1992). "Exploring the strategy-technology connection in small firms". Production and operations Management, Vol.1, No.3, 269-285. |

| [61] | Leonard, D. a. (1998). The Role of Tacit Knowledge In Group Innovation. California Management Review, Vol 40, No. 3, 112-131. |

| [62] | Levrato, N. (2002). "Diversité des mondes de production et des voies d'accession à la rentabilté des petites entreprises: une analyse par les cartes auto-organisatrices". 6e Congrès international francophone sur la PME, Octobre. HEC-Montréal . |

| [63] | Lorenzoni, G. a. (1999). "The leveraging of interfirm relationships as a distinctive organizational capability: a longitudinal study". Strategic Management Journal, 20, 317-338. |

| [64] | Lumpkin, G. a. (1996). "Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance". The Academy of Management Journal, 21, 135-172. |

| [65] | Malhotra, N. (2004). "Marketing research: an applied orientation" (4th Edition ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Prentice-Hall. |

| [66] | McDaniel, C. a. (2001). "Marketing research essentials" (Third Edition ed.). Cincinatti: OH: South-Western College. |

| [67] | McDonough, E. I., & Leifer, R. (1983). Using simultaneous structure to cope with uncertainity. Academy of Management Journal, Vol 26, 727-735. |

| [68] | Megicks, P. (2007). Levels of strategy and performance in UK small retail businesses. 45(3, pp 484-502). |

| [69] | Miles, I. (2008). Patterns of Innovation in service industries. IBM Systems Journal, Vol 47, No,1, pp 115-128. |

| [70] | Miller, D. (1983). "The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms". Management Science, 29(7), 770-791. |

| [71] | Miller, D. (1993). "The architecture of simplicity". Academy of Management Review, Vol.18, No.1, 116-138. |

| [72] | Miller, D. a. (1983). "Strategy-making and environment: The third link". Strategic Management Journal, 4(3), 221-235. |

| [73] | Morgan, R. a. (1999). "Relationship-based competitive advantage: the role of relationship marketing in marketing strategy". Journal of Business Research, 46(3), 281-290. |

| [74] | Morris, M. H., Kocak, A., & Oer, A. (2007). Competition as a small business strategy: Im[;ications for performance. 18(1). |

| [75] | Mouton, J. (2001). "How to succeed in your master's and doctoral studies: A South African guide and resource Book". Pretoria: Van Schalk Publishers. |

| [76] | NEPRU. (2002). "The SME Sector in Namibia: Development of tools for monitoring and an indicative assessment". Windhoek. |

| [77] | NEPRU. (2005). "SME Development and Impact Assessment 2004". Windhoek. |

| [78] | Nueman, W. (2003). "Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches" (5th Edition ed.). Boston: Pearson Education. |

| [79] | Nunes, M. B., Annansingh, F., Eaglestone, B., & Wakefiled, R. (2006). Knowledge management issues in knowledge-intensive SME's. Journal of Documentation, Vol 62, Ni.1, pp 101-119. |

| [80] | Nunnally, J. (1978). "Psychometric theory". New York: McGraw-Hill. |

| [81] | Oliver, A. (2001). "Strategic alliances and the learning life-cycle of biotechonology firms". Organization Studies, 22, 467-489. |

| [82] | Özsomer, A. C. (1997). "What makes firms more innovative? A look at organizational and environmental factors". Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol.12, No.6, 400-416. |

| [83] | Parker, H. (2000). Interfirm Collaboration and the new product development process. 100(6), 255-260. |

| [84] | Perry, C. (1998). "A structured approach for presenting theses". Australasian Marketing Journal, 6(1), 63-85. |

| [85] | Pittaway, L. R. (2004). "Networking and innovation: a systematic review of evidence". International Journal of Management Reviews, 5, 137-168. |

| [86] | Powell, W. K.-D. (1996). "Interorganizational Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology". Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, pp. 116-145. |

| [87] | Raymond, L. (2000). "Mondialisation, économie du savoir et competitivité: Un cadre de veille des tendances et enjeux stratégiques pour la PME.". Gestion, Vol.25, No.2, 29-38. |

| [88] | Raymond, L. a. (1997). "Adopting EDI in a network enterprise: the case of subcontracting SMEs". European Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Vol.3, No.3, 165-175. |

| [89] | Raymond, L. a.-P. (2002). "Performance Effects of Commercial Dependency for Manufacturing SMEs". In D. a. Moore, International Business Trends: Contemporary Business Readings (pp. 133-142). Florida: National Meeting of the Academy of Business Administration. |

| [90] | Raymond, L. a.-P. (2004). "Models and patterns of strategic development for manufacturing SMEs". |

| [91] | Ren, L., Xie, G., & Krabbendam, K. (2010). Sustainable competitive advantage and marketing innovation within firms. 33(1, pp 79-89). |

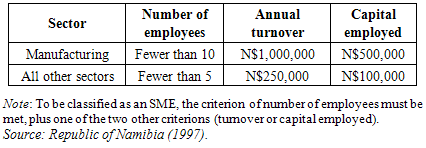

| [92] | Republic of, N. (1997). "Namibia: Policy and Programme on Small Business Development". |

| [93] | Riemenschneider, C. a. (2000). "What small business executives have learned about managing information technology". Information & Management, Vol.37, 257-269. |

| [94] | Rodrik, D. (2004). Industrial Policy for the twenty-first century. John F Kennedy School of Government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. |

| [95] | Roper, S. a. (2002). "Product innovation and small business growth: A comparison of the strategies of German, U.K. and Irish companies". Research Policy, Vol.31, 1087-1102. |

| [96] | Runyan, R., Droge, C., & Swinney, J. (2008). Entrepreneurial Orientation versus Small business Orientation: What are their Relationship to Firm Performance. \journal of Small Business Management, Vol 46,No. 4, pp 567-588. |

| [97] | Saunders, M.,. (1997). "Research methods for business students". London: Financial Times Publishing. |

| [98] | Scheepers, M. (2007). "Entrepreneurial Intensity: the influence of Antecedents to corporate entrepreneurship in firms in South Africa". Unpublished Philosophiae Doctor Thesis, 130-279. |

| [99] | Schumpeter, J. (1934). "The Theory of Economic Development: An Enquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle". Cambridge: Mass. Havard University Press. |

| [100] | Sekaran, U. (1992). "Research methods for business: A skill building approach" (2nd Edition ed.). New York: John Wiley. |

| [101] | Sethuraman, R. A. (1988). "Partnership advantage and its determinants in distributor and manufacturer working relationships". Journal of Business Research, Vol.17, 327-347. |

| [102] | Sherer, S. A. (2003). Critical success factors for Manufacturing Netwroks as Perceived by Network Coordinators. Journal of Small Business Management, 41(Issue 4), 325-345. |

| [103] | Simon, M. E. (2002). "The successful product pioneer: maintaining commitment while adapting to change". Journal of Small Business Management, 40(3), 187-203. |

| [104] | Skandalakis, A. a. (2001). "Benchmarking as a diagnostic process to increase the competitiveness of Small and medium-sized Manufacturing Enterprises". International Journal of Business Performance Management, Vol.3, Nos2/3/4, 261-275. |

| [105] | Smedlund, A. &. (2007). The Role of KIBS in the IC development of regional clusters. Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol 8, No.1, 159-170. |

| [106] | StatSoft, I. (2007). "STATISTICA (data analysis software system): version 7.1". |

| [107] | St-Pierre, J. a. (2003). "Innovation in Canadian SMEs: The process, characteristics of firms and their environment". International Council for Small Business, 48th World Conference. Belfast. |

| [108] | Stuart, T. (2000). "Interorganizational Alliances and The Performance of Firms: A Study of Growth and Innovation Rates in a High-Technology Industry". Strategic Management Journal, 21, 791-811. |

| [109] | Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, Vol 18 No.7, pp 509-533. |

| [110] | Terre Blanche, M. a. (2002). "Research in practice: applied methods for the social sciences". |

| [111] | Thong, J. (1999). "An integrated model of information systems in small business". Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol.15, No.4, 187-214. |

| [112] | Tobias, R. (1997). "An introduction to partial least squares regression". Retrieved March 10, 2009, from http://ftp.sas.com/techsup/download/technote/ts509.pdf. |

| [113] | Trim, P. R., & Lee, Y.-I. (2008). A Strategic Approach to sustainable partnership development. 20(3, pp 222-239). |

| [114] | Tull, D. a. (1993). "Marketing research: Measurement and method" (6th Edition ed.). New York: Maxwell MacMillan International. |

| [115] | Tushman, M. L. (1996). Ambidextrous Organisation; Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change. California Management Review, Vol 36, No 4,8. |

| [116] | van den Ende, J. a. (2001). "The organization of innovation in the presence of networks and bandwagons in the new economy". International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol.31, No.1, 30-45. |

| [117] | Van Dijk, B. D. (1997). "Some new evidence on the determinants of large and small-firm innovation". Small Business Economics, 9, 335-343. |

| [118] | Vargha, R. a. (2001). "Internet Issues for Small ansd Medium-sized Australian Business". Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy (ANZMAC) conference. Auckland: Massey University (Albany Campus). |

| [119] | Walter, A. A. (2006). "The Impact of Networking Capabilities and Entrepreneurial Orientation on University Spin-off Performance". Journal of Business Venturing, 21, 541-567. |

| [120] | Welman, J. a. (2002). "Research Methodology" (2nd Edition ed.). Cape Town: Oxford Southern Africa. |

| [121] | Wiklund, J. (1999). "The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationship". Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 24, 37-49. |

| [122] | Wincent, J. a. (2005). Personal traits of CEOs, inter-firm networking and entrepreneurship in their firms: investigating strategic SME network participants. "Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship", 10, 271-284. |

| [123] | Wince-Smith, D. (2005). Innovate at your own risk. Harvard Business Review, Vol 83, No. 5, pp 25. |

| [124] | Wold, H. (1981). "The fix-point approach to interdependent systems". Amsterdam: North Holland. |

| [125] | Wold, H. (1985). "Partial Least Squares". In K. a. Samuel, "Encyclopedia of statistical sciences" (Vol. 6). New York: Wiley. |

| [126] | Yeoh, P.-L. (2009). Realised and potential absorptive Capacity: Understanding their antecedents and Performance in the Sourcing Context. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 21-36. |

| [127] | Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive Capacity: A Review, reconceptualisation and Extension. Academy of Management Review, Vol 27, No.2, pp 185-203. |

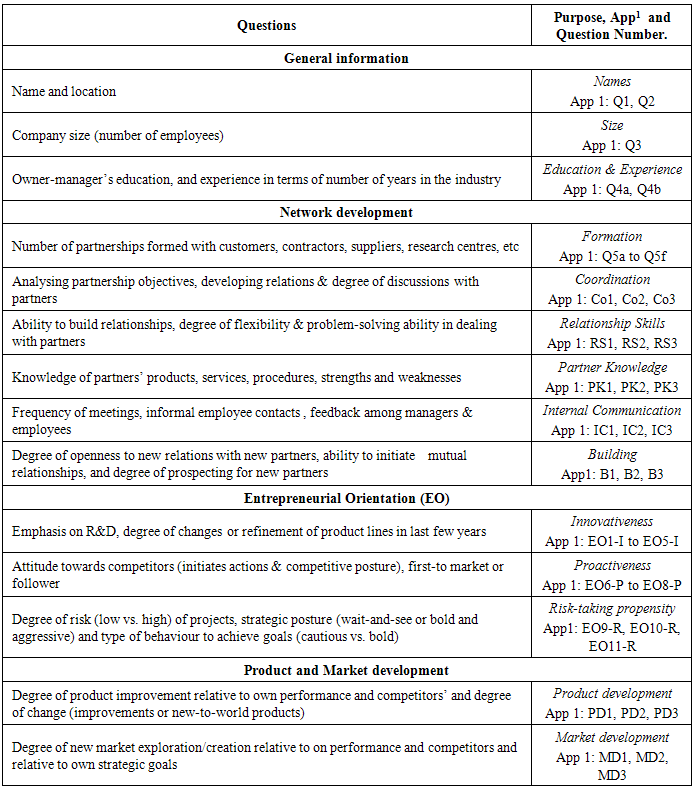

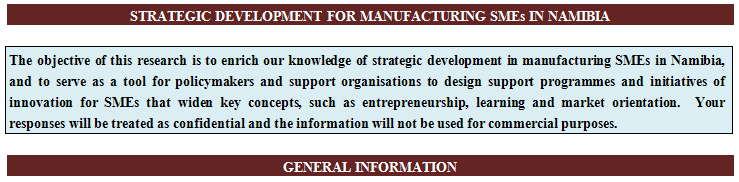

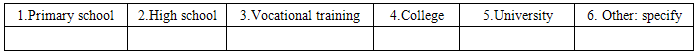

Q1. Name of Organization: --------------------------------------------------------Q2. Location (Town): ---------------------------------------------------------------Q3. Number of employees: ----------Q4a. Owner-manager’s highest level of education (choose one):

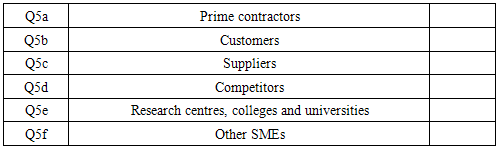

Q1. Name of Organization: --------------------------------------------------------Q2. Location (Town): ---------------------------------------------------------------Q3. Number of employees: ----------Q4a. Owner-manager’s highest level of education (choose one): Q4b. Owner-manager’s industry experience (number of years in the industry): ---------------Q5. How many partnerships have you formed with the following?

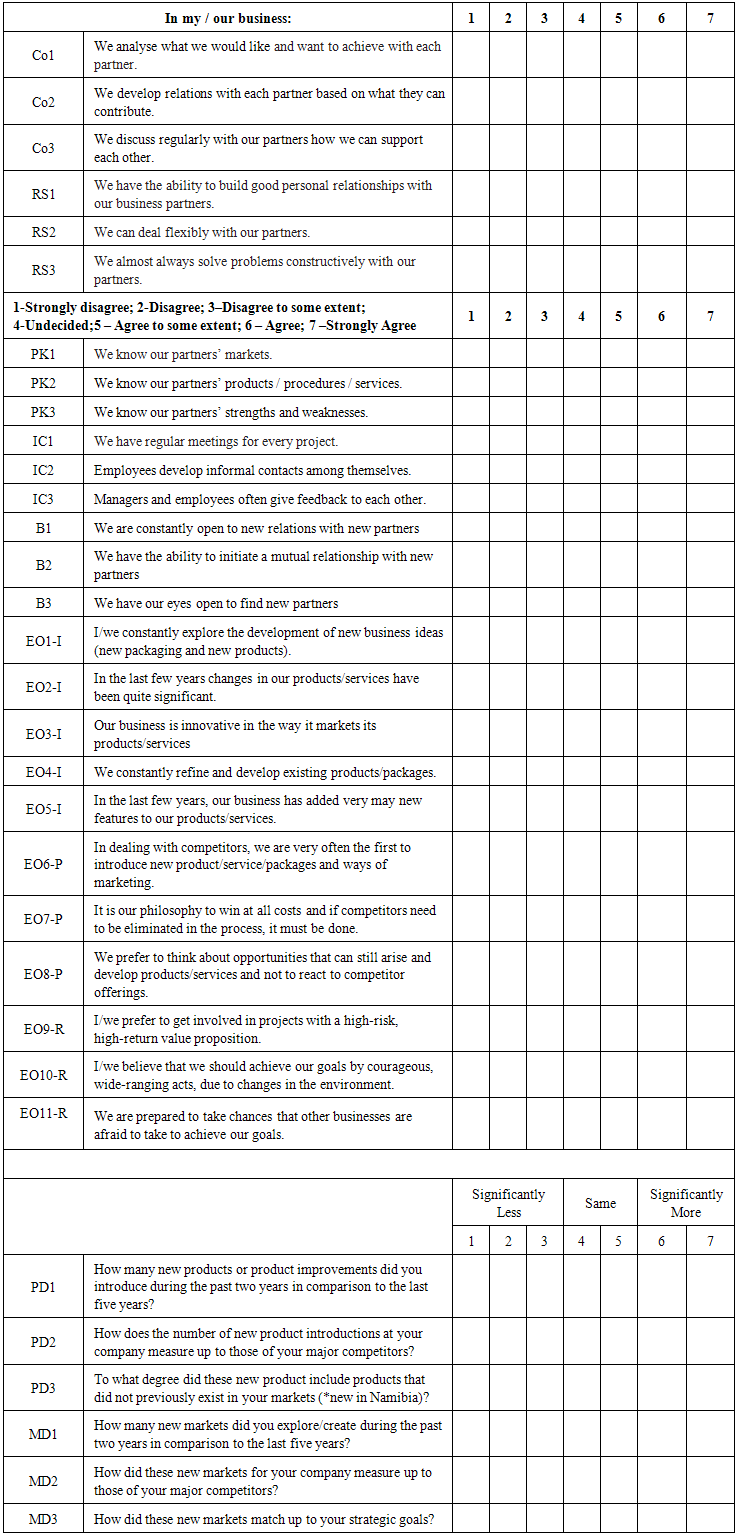

Q4b. Owner-manager’s industry experience (number of years in the industry): ---------------Q5. How many partnerships have you formed with the following?  Please rate your agreement (7) or disagreement (1) with the following statements:We are interested in learning about how you think about your businesses’ strategy and how you see your partners (prime contractors, customers, suppliers, competitors, bank and other partners). If you strongly agree, answer "7", if you strongly disagree, answer "1". There are no right or wrong answers to these questions, so please be as honest and thoughtful as possible in your responses. All responses will be kept strictly confidential.1-Strongly disagree; 2-Disagree; 3–Disagree to some extent; 4-Undecided; 5 – Agree to some extent; 6 – Agree; 7 –Strongly Agree

Please rate your agreement (7) or disagreement (1) with the following statements:We are interested in learning about how you think about your businesses’ strategy and how you see your partners (prime contractors, customers, suppliers, competitors, bank and other partners). If you strongly agree, answer "7", if you strongly disagree, answer "1". There are no right or wrong answers to these questions, so please be as honest and thoughtful as possible in your responses. All responses will be kept strictly confidential.1-Strongly disagree; 2-Disagree; 3–Disagree to some extent; 4-Undecided; 5 – Agree to some extent; 6 – Agree; 7 –Strongly Agree

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML