-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2015; 5(2): 40-47

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20150502.03

Identifying Determinants of Knowledge Transfer in Collaborative Process: A Multi Case Study Approach

Morteza Bazrafshan, Mohammad Aghdasi

Faculity of Engineering, Tarbiat Moderes University, Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Morteza Bazrafshan, Faculity of Engineering, Tarbiat Moderes University, Tehran, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Collaborative processes involve two or more independent organizations engaged in interaction with each other, working towards common goals and share risks, benefits and their resources. Knowledge transfer is an important part of this kind of processes, so it is important to answer the question that what are the factors that affect knowledge transfer in collaborative processes? There are limited researches on this issue, so it is our main contribution to study determinants of inter-organizational information and knowledge transfer in collaborative processes. A questionnaire-based survey was conducted in two collaborative processes selected from public and private sector. Collected data were analysed using structured equation modelling. According to our finding, knowledge nature, technical tools and similarity are important determinants of knowledge transfer. Also organizational leadership have positive effect on it only in private sector. In addition to this, we concluded that a good operational protocol can improve knowledge transfer by removing risk from inter organizational relationship and giving a positive role to senior manager of organizations.

Keywords: Collaborative process, Knowledge transfer, Operational protocol

Cite this paper: Morteza Bazrafshan, Mohammad Aghdasi, Identifying Determinants of Knowledge Transfer in Collaborative Process: A Multi Case Study Approach, Management, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 40-47. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20150502.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Inter-organizational collaboration is increasingly assumed to be necessary and desirable as a strategy for business environments challenges [1-3]; this lead to emerge collaborative processes. Collaborative processes involve two or more independent organizations engaged in interaction with each other, working toward common goals. These organizations share risks, benefits and their resources such as human resource, organizational knowledge and etc. [4-8]. Collaborative business processes help organizations to create dynamic and flexible collaborations to synergically adapt to the changing conditions, and stay competitive in the global market [7]. There are various factors that need to be properly managed in order to achieve an effective collaborative process; If not, it is possible that this type of processes can result in problem such as internal and external conflicts, cost increase and loss of customer satisfaction [5, 9, 10]. During collaborative processes development, inter-organizational information sharing is important when critical information for running sub-processes are usually scattered around independent organizations [1, 9-13], thereby knowledge sharing has increasingly become an important issue for the collaborative processes [5, 14-17]. Importance of knowledge sharing in collaborative processes causes to organizations shift from a model that emphasized information protection to one where cross-organization information sharing is the new goal [11, 14, 16, 18-21]. Although inter-organizational knowledge sharing in collaborative processes has received more attention, initiatives often fail due to various reasons [16, 18, 19, 22-25]. Accordingly, there has been considerable interest in the factors that may influence inter-organizational knowledge sharing, but literatures have focused on inter-organizational knowledge sharing in collaborative supply chain, virtual organizations, and multinational organizations. Also, there is no comprehensive study on determinants of knowledge sharing in the context of collaborative processes. Given these gaps in the literature, this article contributes to understanding of knowledge sharing in the collaborative processes through a multi case study approach. A questionnaire-based survey was conducted in two collaborative processes selected from public and private sector. Collected data were analyzed using structured equation modelling, in order to test the measurement model using confirmatory factor analysis, and to test the structural model.Structure of this paper is as follows. Firstly, a literature review regarding relevant determinants of knowledge sharing in collaborative processes and collaborative processes definition. Secondly, the research methodology followed for the development of this research is explained. Thirdly, provide the analysis and discussion of our findings. Finally, conclusions and research implications are presented.

2. Literatures Review

2.1. Collaborative Process Definition

- There is a bilateral relationship between collaboration and collaborative process [4]. Collaboration needs common goals, language and experiences which should be shared in a specific environment [26]. In another definition collaboration is defined as a process in which independent organizations align their strategies and decisions [27].In collaborative processes two or more organizations collaborate to realize shared goals; so working more than one organization, is one of the most important feature [28]. In this case each organization shares its capabilities [29]. Qiming and Meichun define collaborative process as a process established according to a specific protocol two or more independent organizations [30]. According to literature review features of collaborative process are gathered in Table 1.

|

2.2. Knowledge Sharing

- According to the literature, there is a difference between knowledge sharing and transfer. Knowledge transfer is a more general concept that knowledge sharing. Knowledge transfer typically has been used to describe the movement of knowledge between different units, divisions, or organizations rather than individuals [40]. [41] Argue that barriers of inter-organizational knowledge transfer are knowledge-related such as the recipient's lack of absorptive capacity, causal ambiguity, and an arduous relationship between the source and the recipient. Riege try to offer comprehensive list of actions that help managers to prevail over numerous internal knowledge transfer barriers in multinational corporations (MNCs). He classified barriers in 3 classes, people barriers, organizational barriers and technological barriers [42]. Zapata and his colleagues examined knowledge generation and transfer in information technology-related small and medium enterprises (SMEs). By this, firm’s strategic planning process should include the knowledge to be transferred. Also, the attitudes and abilities of those who take part in the transfer process are important for knowledge transfer, especially for tacit knowledge transfer [43]. In addition some factor such as organizational culture and leadership behavior can have a strong effect on knowledge creation and transfer processes [44]. Knowledge transfer can have some risks for organizations whom participate in it. Loosing organization autonomy, leaked confidential information and knowledge and abusing it can make risks for participating organizations. Knowledge can be source of organizational power and its loss can threat organizational power in the business environments, so organizations avoid inter-organizational knowledge sharing [22]. Intellectual property law, Identification of roles and responsibilities, respecting the autonomy of the parties and the authorizing organizations wisely can build trust between the parties and reduce risk of inter-organizational knowledge sharing [19].In knowledge transfer, power game can raise risk. Power games are defined as the unadjusted use of power to increase the value or influence an individual or workgroup in an organization. Knowledge and information can be a source of power in organizations. In another word, knowledge and information is considered as an asset and can be used for evaluating organizations power, so information sharing can be viewed as a loss of power. The more power games exist, the less sharing of information and knowledge occurs [19, 45-47]. Another barrier to inter-organizational knowledge transfer is conflict. Conflict is defined as ‘‘an expressed struggle between at least two inter–dependent parties who perceive incompatible goals, scarce rewards, and interference from the other party in achieving their goals’’. This kind of conflict is dysfunctional conflict. Dysfunctional conflict constitute behaviors such as distorting information to harm other decision makers, interacting with each other with hostility and distrust or forming barriers during the process of decision-making [16]. Conflict can be managed by aligning between common goals of inter-organizational relations and exclusive goals of organizations [48].Interpersonal similarity is another key driver behind inter-organizational knowledge transfer. Also inter-organizational similarity have same effects. Some dimensions of interpersonal similarity are religious, cultural background, shared language, organizational status, social and job position, capability and accepted value. Interpersonal similarity leads to a higher tendency for interaction, increasing the sharing of business knowledge [46, 49]. Inter-organizational similarity can be evaluated according to organizational values and culture, joint activity, same position in the business environment or workplace and etc. [49]. Organizational and individual similarity can create a common language between organizations. So it can facilitate knowledge transfer by increasing trust between them. Also having a shared vision, planning horizon and absorptive capacity, job stability, control systems and etc…. help organization to trust to each other and improve quality and quantity of knowledge transfer consequently [50, 51].Organizations management and leadership have an inescapable effect on inter-organizational knowledge sharing. Organization management can facilitate inter-organizational knowledge sharing by setting a good strategy, providing required resources and etc…. A good strategy can facilitate reaching agreement between organizations and prevent from dysfunctional conflicts. These effects can be augmented by executive interference, creating formal authorities and authorizing proper person and conduct inter-organizational relationships informally [7, 52]. The ability of an organization for receiving and using information from other organizations is in association with used information technology [4]. Information technology is a physical way for connecting organizations; but technology alone cannot establish connection. Before using technical tools for inter-organizational information transfer it is necessary to check consistency of organizations hardware and software. Also Tools are used by the parties, should be able to communicate with each other. The ability of personnel’s of organizations to use tools is important too [20, 50]. The tools should have the capability of storing, classifying and managing received information [53]. Type of tools and technology can be determined by knowledge nature. Knowledge characteristics such as being implicit, explicit, and vague or its complexity can change rate of knowledge sharing and also usability of received knowledge. accordingly vagueness of knowledge is a barrier to knowledge sharing [19]. Like knowledge nature, knowledge architecture is important in knowledge sharing too. Knowledge architecture is defined as structure and location of knowledge, degree of simplicity and explicitly and how to attach to various parts of processes and organization departments [54].

3. Research Design

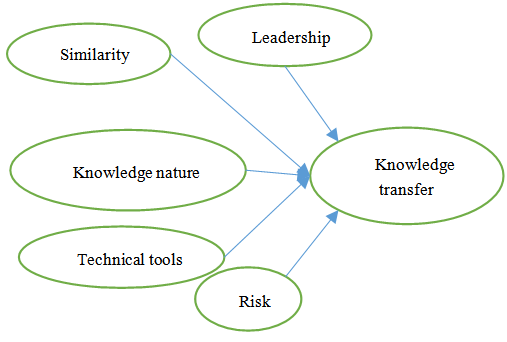

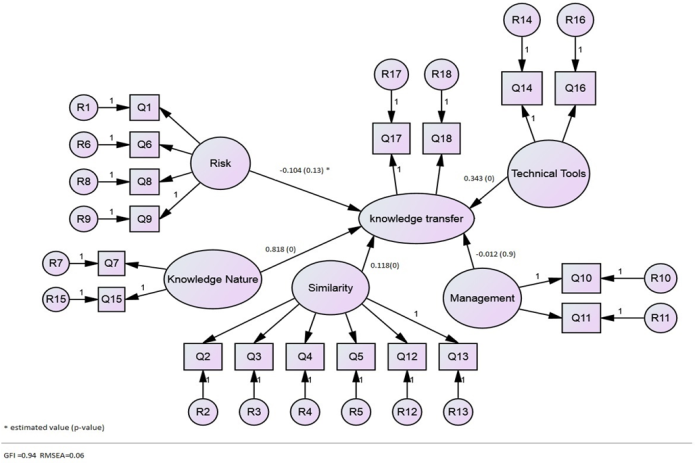

- According to our literature review risk, similarity, technical tools, knowledge nature and organizational leadership are important determinants of knowledge transfer; but there are no researches on collaborative processes, so our conclusion were based on literatures that focused on multinational company, collaborative supply chains and virtual companies. Theses situation are similar to collaborative processes, so this study develops following hypothesizes about factors that affect knowledge transfer in collaborative processes and test them in two real collaborative processes.Hypothesis 1: risk of invalid knowledge and abuse of transferred knowledge can have negative effects on inter-organizational knowledge transfer in collaborative processes.Hypothesis 2: interpersonal and in reorganizational similarity can have positive effects on inter-organizational knowledge transfer in collaborative processes.Hypothesis 3: knowledge nature can change rate of inter-organizational knowledge transfer in collaborative processes.Hypothesis 4: technical tools used in collaborative processes can have positive effects on inter-organizational knowledge transfer.Hypothesis 5: organizations leadership can have positive effects on inter-organizational knowledge transfer in collaborative processes.Hypothesizes are shown in Fig 1.

| Figure 1. Primary research model |

4. Research Methodology

- This study adopts a multi case study method to extend current literature finding about inter-organizational knowledge sharing to a different context. In particular, two different cases have been selected, one from private sector and the other one from public sector. Process of determining inheritance tax in Iran tax administration from public sector and process of power plant construction in MAPNA group from private sector have been selected for gathering data.This study measured six constructs: risk, leadership, technical tools, similarity, knowledge transfer, and knowledge nature. All constructs were measured using multiple items measured on a seven-point Likert scale (from ‘‘strongly disagree’’ to ‘‘strongly agree’’). Two questionnaires were designed for gathering data one for MAPNA group and one for tax administrations). These questionnaire designed based on previous research [55]. Finally we modify questions sentences for better understanding by use of experts’ comments in two cases. Stratified sampling was used according to the population of each subsidiaries in MAPNA group and organizations in tax administration.Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) were used to test the hypotheses. AMOS (22.0) was used to conduct CFA and SEM analysis and SPSS (22.0) was used to conduct standard statistical analysis.

5. Cases Description

- There are number of characteristics that indicate differences between public and private sector. For instance, there seems to be varying degree of executive control among the employees of these two sectors. Other differences include organizing principles, structures, performance metrics, relationship with end users, nature of employees, sources of knowledge, ownership, performance expectations, incentives, etc. [56-58]. For more details see [59]. According to these differences cases were selected form private and public sector.

5.1. Process of Determining Inheritance Tax in Iran Tax Administration (Public Sector)

- Iran national tax administration (ITNA) is intended to provide all requirements needed for administrating tax plans and for doing legal duties concerning tax collection as efficiently as possible. This administration is a government institution established under the supervision of the minister of economic affairs and finance. Tax re-source such as inheritance tax, direct tax, indirect tax, tax on incidental income and etc. were defined by this administration. Each of these tax resources has own experts and processes. In this research for determining the boundary of the case and restricting data gathering process, studied case was limited to the process of determining inheritance tax. This process is an inter-organizational process in which inheritance tax determined by collaboration of governmental and non-governmental organizations such as tax administration, banks, minister of foreign affair, Judiciary and etc. This collaboration established by requesting information from other organizations. Collaboration will be stopped if inter-organizational information flow stopped. According to these we can conclude that this process is useful for our research.

5.2. Process of Power Plant Construction in MAPNA Group (Private Sector)

- MAPNA Group is a group of Iranian companies involved in construction and installation of energy production machinery, including boilers, gas and steam turbines, electrical generators, as well as industrial scale petroleum processing installations, railway locomotives and wind power. The company Iran Power Plant Projects Management Company (MAPNA) was founded in 1993 with the aim of developing indigenous knowledge production capacity for petroleum facilities, power plants and other industrial facilities, and as a contract management company. MAPNA group is a conglomeration of the parent company with 33 subsidiaries.Process of power plant construction were started by a contract between ministry of energy and MAPNA group. MD-2 plays a vital role among MAPNA GROUP subsidiaries in terms of Management Contract (MC) services as well as EPC contracts for implementation of Power Plants. This role can be played by MD-1 or MD-3 too. Detailed design of project were done by Monenco. Power plants projects require procurement of equipment’s. Mapna Group has set up a mighty and powerful chain for the procurement of goods and services inside and outside of Iran. By completing detailed design, it is possible to start procurement chain. International MAPNA provides foreign financial services (if it is needed). Design, supplying, manufacturing, installation and commissioning of different types of power plant hardware such as boilers, turbines and its blades and electrical & control systems were done by MECO, Boiler, PARS and other subsidiaries. MD-2 selects contractors for installation of Software’s and Hardware’s. During installation and warranty period of power plants some feedback were given to subsidiaries to improve their internal processes. Also working jointly makes some implicit supervision on subsidiaries.

6. Results Presentation and Analysis

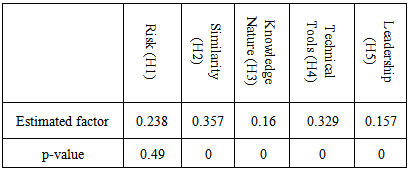

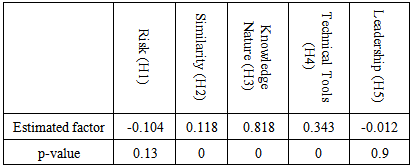

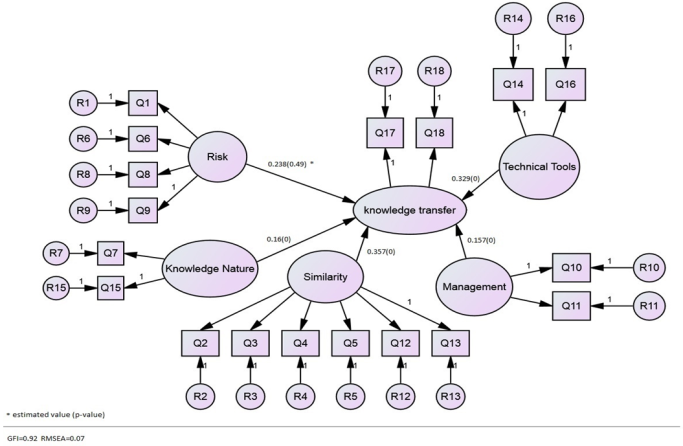

- In case of MAPNA group a total of 124 usable responses were returned, yielding an effective response rate of 62.0%. Factor analysis was conducted to assess the constructs. Reliability of our construct scales was estimated through composite reliability. Composite reliability was calculated using the procedures suggested by [60]. The composite reliabilities for the six constructs scales suggested acceptable reliability of the scales for further analysis (knowledge transfer: 0.79, leadership: 0.82, technical tools: 0.83, similarity: 0.81, and risk: 0.87). Cronbach’s alpha for each of the six construct were greater than 0.72, revealing satisfactory reliability of our questionnaire. Estimated model is showed in Fig 2.

| Figure 2. Estimated structural model of MAPNA case |

|

|

| Figure 3. Estimated structural model of TAX administration case |

7. Conclusions

- While the research has made significant contribution to determinants of knowledge transfer in collaborative processes, there are limitation that need to be considered when interpreting study finding. Because of our limitation in finding and selecting case, using our finding should be done carefully. New data may be collected from different cases to revalidate our finding. Also, it would be interesting to investigate determinants carefully in different cases. In another word it will be useful if knowledge nature, similarity, technical tools investigated in context of cases. Future research should also answer questions like "what are the main dimensions of similarity, technical tools and knowledge nature in collaborative processes?"

Notes

- 1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MAPNA_Group2. http://www.mapnagroup.com/

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML