-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2015; 5(1): 15-23

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20150501.03

The Role of the Informal Sector in the Development of Entrepreneurship in Senegal: Background and Justification

Boubacar Basse

PhD in Management Science, Head of Economics Department Management, Assane Seck University of Ziguinchor, Ziguinchor

Correspondence to: Boubacar Basse, PhD in Management Science, Head of Economics Department Management, Assane Seck University of Ziguinchor, Ziguinchor.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In general, informal activities have always been well accepted in Senegal, and the rest of Africa as well. From this point of view, they are all the time, well integrated into society. This means therefore that the economic and social importance of the informal sector does no longer need evidencing. Through an exploratory methodological approach, this article aims to analyze, from the entrepreneurial model of Ahmad and Hoffman (2007) [1], new conditions for the emergence of a modern entrepreneurship resulting from the eradication and the progressive inclusion of the informal sector into the modern economy in Senegal. Beyond the debate on eradication and / or inclusion of the informal sector in the modern economy, it is to see whether the emergence of the informal sector is a foreshadowing of microenterprises and modern SMEs. Five aspects to apprehend the changes in the business environment are addressed here: the new relationship to the company, the business models of reference, the incentive scheme for formalization, financing and business environment.

Keywords: Informal economy, Entrepreneurship, Company, Business environment, Senegal

Cite this paper: Boubacar Basse, The Role of the Informal Sector in the Development of Entrepreneurship in Senegal: Background and Justification, Management, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 15-23. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20150501.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The informal sector plays a leading role in the African economy in general and Senegal in particular. Some five million Senegalese people "excluded" from the conventional economy meet there at a time when the said modern sector is slowing. In addition to that the founding and management of a modern company is so complex that the "formal" entrepreneurship inspires distrust or even revulsion on the part of the public opinion. Thus, to dodge the harassment from the formalization of economic entities with their tax-related, financial and regulatory obligations... many entrepreneurs operate outside the modern economy by conducting often prosperous activities that generate millions jobs for the workforce. In doing so, the debate remains open at the level of certain professional organizations and employers authorities as to whether to back up or eradicate the informal sector, knowing that the Civil Service and the traditional private sector cannot absorb all the mass unskilled workers. The latter can find job opportunities in the production units of the informal economy (small shops, wood and metal construction workshops, garages ...) whose development is uncontrollably found in residential neighborhoods, leading to an exposure to various types of risks.This means therefore that the economic and social importance of the informal sector does no longer need evidencing. To be more convinced, simply "ask how Senegalese households are supplied with staples, how industrials make their products accessible on the national territory, how professionals in Building and Public Works can find labor, how farmers distribute their products in large markets, ask banks who their best customers are in terms of volume of economic transactions, ask the State what economic actors contribute most to social stability and economic growth ... » exclaimed an official of the UNACOIS (National Union of Traders and Industrialists of Senegal). Besides if Senegal is able to cope with external shocks, it is thanks to the dynamism of economic actors in the informal sector.However, despite their multiple advantages, it should be noted that informal enterprises are faced with huge needs for technological equipment. The leaders of these companies often lack appropriate training, managerial and technical skills. In addition, they face enormous difficulties of access to regional and international markets due to failure to adapt their products to international quality standards (packaging, logistics and marketing issues). They also face a funding problem and access to bank credit.The question then arises as to what new conditions for the emergence and development of entrepreneurship in Senegal. Especially today we have to recognize that, thanks to globalization and liberalization of the economy, a new situation lends itself to the development of the company. Clearly, the debate continues as to whether the eradication or the inclusion of the informal sector into the modern economy.The purpose of this paper is to analyze the new conditions for the emergence of a modern entrepreneurship resulting from eradication or gradual inclusion of the informal sector into the modern economy in Senegal. Five aspects to apprehend the changes in the business environment are addressed here: the new relationship to the company, the business models of reference, the new support, promotion and incentive provision to formalization, diversification of financing sources and finally the business environment. Prior to that, a definition of key concepts related to entrepreneurship and the informal sector followed by a presentation of the methodology of the study is being planned.

2. The Entrepreneurial Spirit in Senegal

- Senegalese entrepreneurial tradition is almost bicentennial because going back to great families of the municipalities of Saint - Louis and Goree, called "contractors" who were active in the trade of gum, and later peanuts in partnership with counters of large business houses Bordeaux and Marseille from the colonial era. According to Amin (1969) [2], the history of Senegalese businessmen is marked by the advent of large merchant families, some of which are still well established. This means therefore that the prevalence of Commerce on Industry, in the structure of the national economy, traces back the roots of the Senegalese entrepreneurship.However, by 1950, the Senegalese world business experienced a historic turning point marked by the end of the monopoly of peanuts as subject of commercial transactions. Traders became interested in import of capital goods and dairy products as well as transportation and real estate. The movement will move forward to embrace all sectors of economic activity.

2.1. Entrepreneurship

- According to Julien and Marchesnay (1996) [3], the act of entrepreneurship remains the creation of enterprise, innovation is the mover, the entrepreneur is the actor, the market represents the opportunities and the environment constitutes the incitement to entrepreneurship. From this point of view, we join the approach of Marsden (1991) [4] that identifies entrepreneurs as those who "innovate and take risks. They employ and direct the workforce. They open markets and find new combinations of products and processing of raw materials. They initiate change and facilitate adjustment in dynamic economies. "Innovation implies the emergence of a "novelty" in the sense of Paturel (2007) [5] which includes two practices peculiar to entrepreneurship that are the creation ex nihilo and the takeover. In short, coming within the scope of the position of the above authors that the essence of entrepreneurship is the creation of enterprise, we agree, like Davidsson (2001) [6], that this is specifically (1) the creation of a new business; (2) the takeover of an existing business with minor or major innovations; (3) a new business in a new market; (4) expanding the market for an existing business. The concept of business is also very heterogeneous in reference to many classification criteria. For simplicity, the size is usually used to distinguish the Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) from big businesses. Yet, SMEs is more widespread in Senegal certainly because of its relative flexibility. It covers an ambivalent reality in that it is subject to many definitions. The one proposed in the SME Charter created in 2003 and which has later become the framework law on SMEs since 2008, is fairly representative of the position of the Senegalese authorities on the issue. It shows that the Small Business (SE) / (cf. Art 3 of the Charter) means a natural or legal person, producing goods or commercial services that meet the following criteria and thresholds, with a workforce of between one (1) and twenty (20) employees and/or a minimum annual business turnover of 25 million CFA Francs.A qualitative approach is often preferred to understand the size of the SMEs. It is based on a management characterized by the central role of the leader. Another feature is the uniqueness of the decision-making center for strategic choice compared to large companies in which power is more disseminated (Paquay, 2005) [7].

2.2. Types of Senegalese Entrepreneurship

- Like the vast majority of African economies, four types of companies and production units, identified by Hugon (1995) [8] are the main components of the Senegalese entrepreneurship. These are as follows:Large private companies which are essentially foreign ones that is to say, subsidiaries of foreign multinational groups. They are more visible in the oil sector and / or agricultural exports, and to some extent, import substitution industries, like cement SOCOCIM SA. According to Quiers-Valette (1993) [9], these large foreign companies generally face a series of adverse factors such as narrow markets, economic, financial and political risks, weakness of the local economy, a "predatory" state (fiscally speaking!), a failure of the banking system, inadequate legal and institutional framework ... Nevertheless, these entities meet the criteria of profitability and organizational strategies specific to capitalism.Public and semi-public enterprises: they consist of public industrial and commercial, state companies, joint venture companies. Their role is to substitute for the lack of domestic entrepreneurs. Essentially, these companies experiencing market difficulties due to competition, liquidity and solvency problems ... mainly due to management errors, prevarications, a qualified staff deficiency (Plane, 1993) [10];Small and medium private enterprises, which are considered by the World Bank, in its 1989 report, as the main missing link of the economic fabric. They are still more prevalent in the service sector probably due to the relatively low barriers to entry such as investments. These companies are "90% of the economic fabric of Senegal and contribute for 42% of job creation, 36% of revenues and 33% of the added value" (business magazine "SME Info", January 2010, p.29).Small market informal units: they are relatively numerous. Constituting the so-called "informal sector", these companies are characterized by a low dissociation of the productive and domestic sphere, the lack of permanent wage labor, the lack of accounting and access to the institutionalized credit. Moreover, they devote themselves to a small-scale production targeting an insolvent demand and very unstable. Despite this string of recriminations, Latouche (1989) [11] recognizes certain dynamism to the actors of the informal sector, which in his view, are ingenious and not engineers.This formal / informal sector allocation establishes the duality of entrepreneurship in Senegal. Unlike the modern sector of large enterprises, informal production units have a relative flexibility allowing them to easily adapt to environmental constraints. This great adaptability is their ability to reconcile social and cultural values of Africa with the necessary economic efficiency (Dia 1992) [12]. That is to say, like Taoufik and Angelhard (1990) [13] that the economic systems and processes in informal sector are in "harmony" with the surrounding cultures.

2.3. The Informal Sector in Senegal

2.3.1. Definitions

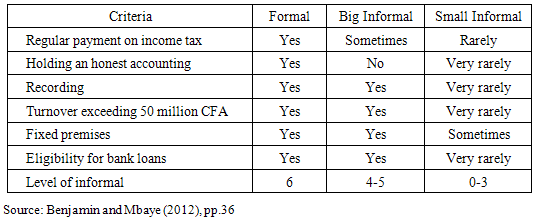

- The Informal is subject to many names and definitions that reflect the vitality of the concept. Thus, the "informal sector" or "unregulated", "black economy" or "unstructured" or "unframed" refers to the same reality known as the unifying term "informal economy" by the International Labour Organization Bureau (ILO). The terminology used by Benjamin and Mbaye (2012) [14] includes all activities which are or not poorly recorded. This is what makes the informal a question of degree rather than status.This approach contrasts with the position of the National Agency of Statistics and Demography (ANDS) in Senegal which raises the issue of the legality of informal comprising in his eyes "a set of production units (PU) without statistical number and / or formal written accounts. »The thesis of the illegality of the informal economy cannot succeed if one refers to the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), which marks a clear dissociation between informal and "illegal economy" which consists of all illicit activities such as drug trafficking and counterfeiting. Nevertheless, a whole section of the informal economy shows strong similarities with the underground economy within the meaning of the OECD since it includes all hidden activities to avoid paying taxes and to avoid other legal obligations.As for the concept of "informal sector", it is due to Keith Hart and dates from the early seventies, on the occasion of the World Programme launched by the International Labour Office (ILO). In the same vein, Meine van Dijk (1986) [15] identified in the 1972 Kenya report seven characteristics to understand the informal sector enterprises: The initial capital is small and consists essentially of personal savings of the entrepreneur and those around him; it is afamily business where parental proximity and ethnic-clan solidarity prevail over purely economic considerations; Resourcefulness is legion to circumvent the lack of resources. It controls the use of local raw materials as well as tools made locally; the necessary skills are acquired through training on the job. Learning occurs primarily through observation or imitation of the oldest in the trade; the production capacity is low in the image of the size of almost all units whose workforce rarely exceeds ten employees; the technology used is rudimentary but is highly labor intensive; the unregulated market is very competitive and open to any potential entrant. By focusing more on informal businesses than on informal employment, Benjamin and Mbaye (2012) use six criteria to define the informal sector: the size of the business, registration, sincerity accounts, fixed workplace, access to credit and the tax status of the firm. They refine their analysis by distinguishing the bulk informal from the small informal (see Table 1). The former are comparable to those of the modern sector, but behave informally in many ways in that they do not meet the criterion of fairness of accounts. As for the latter, they rarely meet these criteria formality.

|

2.3.2. Economic Importance

- The emergence of the informal economy stems from the combination of many factors such as urban migration, population growth and poverty (Marchand, 2005) [18]. According to the ILO report (2004), the share of the informal sector represents 80% of non-agricultural employment, over 60% of urban employment and 90% of new jobs in Africa.In Senegal, the paper study 9 of the Department of Forecasting and Economic Studies (DPEE) dating from October 2008 estimate at 508.8 billion FCFA the production of goods and services and 356.3 billion worth added value in Dakar, due to the informal economy. In addition, informal accounts for 54% of Senegal's GDP (Benjamin and Mbaye, 2012).As for the sector-based distribution, trade represents 46.5% of informal activity in 2003, industry 30.6%, services 21.3% and fishing 1.6% (Forecasting and Statistics Directorate, 2004).Regarding employment, Benjamin and Mbaye (2012) [14] show that the informal sector is predominant in agriculture / livestock with 48.06% of all households operating in this activity. Then trade with 23.6%, followed by other services with 7.4%. Finally, in Senegal as in other WAEMU countries (Benin and Burkina Faso), the informal sector accounts for less than 3% of tax revenues.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Introducing the Adopted Methodology

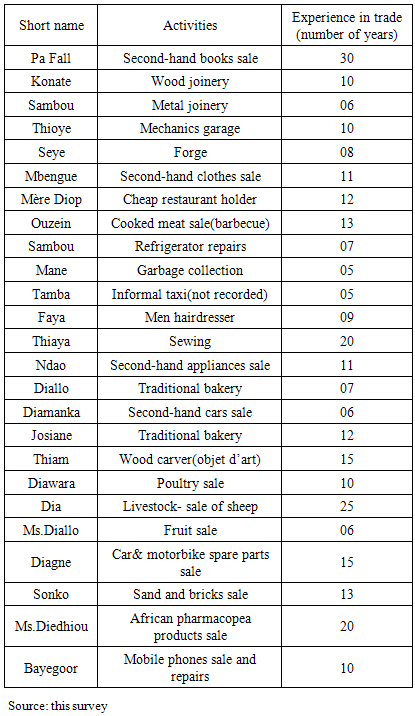

- The methodological approach we have adopted is essentially qualitative. It is based to the method of multi-sites cases in Yin’s sense. Data were collected through non-participant observation and semi-structured interviews with different categories of stakeholders. The use of the two approaches (interview and observation) meets a need to compare different sources of information and thus bring greater validity to research.Thus, 25 leaders of very small enterprises (VSE) operating in the informal sector in Senegal were observed and interviewed between November 2012 and February 2013.This is a purposive sample comprising a total of 25 active VSE in various fields of economic activity (see Table 2).

|

3.2. Collection and Analysis of Data

- All data collected using an interview guide and observation was coded manually and analyzed thematically.The guide includes the following topics:(1) starting a business motivations: profit motive, love of power and prestige, desire for independence and autonomy, family tradition ...(2) entrepreneurial skills: imagination and creativity, risk appetite, sense of public relations, technical skills ....(3) The business environment: entrepreneurial opportunities, sources of supply, solvent market, the absence of regulatory constraints, funding sources, appropriate technology ...

4. Presentation and Analysis of Results

- Observations on the field as well as the analysis of "discourse" allow entrepreneurs to highlight the elements of the model of Ahmad and Hoffman (2007) [1] or the OECD. This model offers determinants of entrepreneurial performance and its impact on the economy, hence its relevance to our research problem. This detailed presentation of the determinants of the OECD model focuses on the regulatory framework, the availability of new technology, entrepreneurial skills, cultural values, access to finance and market conditions.

4.1. Regulatory Framework

- Indeed, the regulatory framework within which informal entrepreneurship in Senegal evolves is generally characterized by a "legal vacuum" that is quite favorable to the various economic operators who are satisfied with. Therefore, the absence of barriers to entry, growth and a bankruptcy law ... provides flexibility to the exercise of an informal economy. Nevertheless certain activities such as the food catering are subject to unannounced inspections by the health authorities, which is not the case of traditional Pharmacopoeia yet prodigal of sensitive products that can dangerously, in some cases, affect the health of users. Similarly, the administrative authorization to build is also a preliminary step to regulate the informal sector of Masonry.It must be admitted that few actors comply with regulatory requirements, deliberately or simply through ignorance of the law because of illiteracy that characterizes this part of the population. The penalties are often mitigated by the ability to "negotiation" of the defaulting traders who are thus forced to "work out" with the officers of the municipal Department of Hygiene, those of the collecting service of daily municipal taxes ... even to bribe to get undue favors.Another highlight in the exercise of economic activities is related to health and safety. Indeed in most production units (PU) visited the risk of explosion, fire, and pollution ... is highly significant. The exhaust gas, petrol and acid stored in garages as solvent vapors, dust, wood joinery or metal fumes in the metal joinery are all harmful elements that alter gradually health workers in these PU. The operator exposure to these various types of risk stems from a lack of vigilance during the tasks, plus the lack of wearing of personal protective equipment (gloves, masks, etc.).

4.2. R & D and Technology

- In technology, besides the scrap iron merchants who carry out its basic processing for the production of various utility items like utensils, informal PU operators are content for much of the technology incorporated in equipment purchased and do not distinguish between technology implementation and equipment acquired. Similarly, if the idea of standards and patents systems remains largely absurd in these environments, efforts "research" are constantly being made to develop product innovations or processes that meet the needs of the market. In the rare event of sewing, manufacture of utensils, traditional Bakery and particularly the traditional pharmacopoeia, "technology" used is subject to strict retention by those who develop it for fear of being competed. The exercise of a monopoly on the key input, which is the technology, is therefore a guarantee for the preservation and even the survival of the business conducted.

4.3. Entrepreneurial Skills

- None of the leaders of the PU visited received an entrepreneurial training but a training on the job. The learning methodology is then to "observe or watch do" by showing "patience, good behavior, obedience and loyalty to master" for the duration of the training. It is therefore a matter of experience gained during the learning process that does not necessarily give right to remuneration. The labor force provided by the apprentice is in return for the training received by the latter.

4.4. Culture

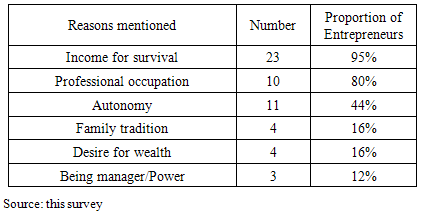

- The majority of VSE (very small enterprises) studied correspond to old experiences dating back at least 10 years. This confirms the finding of "long" tradition of non-regulated activity in Senegal. This is added that many contractors work at home. Our results highlight the fact that almost all of the surveyed entrepreneurs are full-timers and are not looking for a job. In addition they all belong to the age group 20-60 years which is quite favorable in terms of employment accessibility. Therefore, their income derives solely from their entrepreneurial activities. This confirms one of the main reasons for starting an economic activity resulting from the inability to find work in the formal sector (see Table 3).

|

4.5. Access to Finance

- Most entrepreneurs use their personal savings as seed money. None uses a bank credit because of the recurrent inability of the informal sector access to institutional finance. The main constraint is related to the collateral requirement expressed by commercial banks in exchange for financial support. The lack of "transparency" in the tariff conditions applied by banks is also criticized by some operators that mark their preference for mutual savings and credit (see Box 1).Box 1:"Basically, mutuals are more transparent than banks. When mutuals lend you 50 million, you take it in cash. Some procedures are not xistent. It is the same for a fee. The payment method is also clear. Nothing to do with the bank that said, we credit, we charge your account a particular sum.The bank debits even a simple envelope "; "yes I work with banks. but I only deposits funds and when it comes to credit, I go with mutuals "; "I think that the mutual must be able to organize themselves in order to finance some large business investment".

4.6. Market Conditions

- Almost all of the PU visited run product or service activities, using mainly cash. The practice of industrial activity by the studied operators is negligible. Making outsourcing is a widespread activity especially on the eve of festivals and religious events. Accessibility to the internal market is not helped by the poor quality of many of the road infrastructures, especially regarding perishable food products from agriculture. The export of products from the informal activities is reduced to its simplest expression. The reason is that most people interviewed, who are essentially within the small informal sector think administrative procedures are "complex and tedious." In addition, "to dispose of the import – export card, we must have far reaching arms in the government or the ruling political party." Finally, regarding procurement covered by tendering procedures or over -the -counter for the acquisition of goods and / or services, almost all of the entrepreneurs surveyed said "not aware" of the existence of such business opportunities. The fact remains that close cooperation exists between overtly modern enterprises and those in the informal sector, provided that they can issue them "bills" for their accounts (see Box 2).Box 2:"For twenty years I have been selling shrimp and other seafood, my biggest clients are the hotels.The most important sales are during the tourist season. I have before me a book of blank bills I bought from stationery to deliver to customers who request it ... The price put on the bill is sometimes higher than the actual price of the goods. This overestimation of the goods (on paper!) is made at the request and for the benefit of the one who buys the hotel. "

5. Discussion and Managerial Implications

- This is to study the links between the informal sector and the modern sector to see to what extent, companies and small producers can be assimilated to entrepreneurs. Beyond the debate on eradication and / or inclusion of the informal sector in the modern economy, it is to see whether the emergence of the informal sector is a foreshadowing of microenterprises and modern SMEs. All the more so in the current context of globalization and the globalization of markets, the private sector represents a country positioning key factor internationally. Moreover, the creation of public structures accompanying and coaching SMEs participating in this effort to upgrade enterprises in order to benefit from the globalization of markets.Moreover, from a social point of view, the companies play a vital role providing some social cohesion. Due to the limitation of recruitment opportunities in the public service, they are invaluable sources of job creation.

5.1. The New Relationship to the Company

- In general, informal activities have always been well accepted in Senegal, and the rest of Africa as well. From this point of view, they are all the time, well integrated into society, unlike the modern or 'formal' business that was long considered a foreign body (Ponson, 1995) [19]. But according to Hernandez (2001) [20], new rules facilitate entrepreneurship in Africa. They concern: a legal renewal, with the application of the Treaty of OHADA (Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa) by the 16 signatory States in 1993, that is to say, fourteen of the franc zone plus Guinea and Guinea Bissau. This dimension provides legal and judicial security for investors, filling a vacuum qualified "judicial shipwreck" by Marchand (1996) [21] quoted by Hernandez (2001) [20]; a revival of the state which enshrines the disengagement of the State merchant productive sector to play a role in prescribing and encouraging private economic operators to entrepreneurship. ; A renewal of politics with the advent of participatory and inclusive democracy compatible with ethnic diversity. Democracy being good a governance condition, it remains imperative for the establishment of foreign investors especially those from Western countries.We must add to this movement the advent in 1998 of SYSCOA (West African Accounting System) common to all the countries of the Economic and Monetary Union of West Africa (UEMOA). With the application of this basis, many African companies were able to seize the opportunity to keep regular accounts in one of three accounts presentation systems (normal system, reduced system and minimum cash system) compatible with the size and nature of their activities.The generational alternation is also instrumental in the change of relationship of the society to the company. This is precisely the arrival in national economic sphere of many entrepreneurs trained in "best" management practices as abroad (France, Canada, and United - States, England ...) at the local level in universities and private business schools well established in the country. This fact is related to the spread of management education in general and entrepreneurship in particular in the private higher education institutions (EPES) and public universities.

5.2. Some Entrepreneurial Reference 'models'

- In the world of Senegalese business, success stories and examples of success never fail to be emulated in the population, especially young people in search of reference models. We can cite the example of Yérim Sow. The choice focused on the businessman known and recognized both nationally and internationally is justified by the fact that it is in every respect a success story to inspire many young Senegalese and Africans. Being mainly active in the Telecommunications, Banking, and Real Estate ... he has a fortune estimated at 150 billion CFA francs (€ 228.7 million). His entrepreneurial talent allowed him to have to his credit a lot of creation of modern enterprises.Other entrepreneurial profiles also have emerged. The magnitude of the phenomenon is so important that the business magazine called "SUCCESS" devoted his No. 61 (December 2011) at the Senegalese family entrepreneurship. This is, among other references, Youssou Ndour and Serigne Mboup. These two businessmen share a common characteristic in the sense that unlike Yérim Sow, they did not study in French even less in management. Their companies are moved gradually from the informal to the formal sector. The first is a musician - composer, responsible for several companies (Radio Future Media, Future Media Television, recording studios and music production ...). The second succeeded his father as head of the legendary group BCCM (Comptoir Commercial Bara Mboup) whose activities straddle the food industry and trade equipment.To reward initiative and success while honoring the path of copies of business leaders, employers' organization like the Senegal Enterprises Movement (MEDES) publicly awarded the "Golden Cauris" to the "best" entrepreneur of the year. Also, on the side of the Ministry, It has been established, in 2011, a ceremony called "the industry Diamonds" intended to magnify and amplify every three years, the efforts and the performance achieved by economic actors (goods and services) in terms of competitiveness, innovation and job creation.These honors have not only a stimulating and undeniable aim and an influence on the rewarded leaders, but also a ripple effect to an audience with the ambition to build leading companies of tomorrow, capable of radiating internationally (Gompers et al., 2010) [22].By the creativity and perseverance of entrepreneurs, the firm is no longer regarded as an organization whose "essential" function is to pay taxes to the State, in the long, languishing under the weight of expenses and debts and proceed to dismissals (often abusive) of its staff. The modern or formal company is now seen as a means of upward mobility that can legitimately provide total satisfaction to all human needs identified by Maslow in his famous pyramid.

5.3. The New Accompanying Institutional System and Promoting Entrepreneurship

- Through its commitment to the private sector to play a leading role in the process of economic emergence of the country, the Government of Senegal has set up in 2001, the Agency for Development and Supervision of Small and Medium Enterprises (ADEPME) as the operational structure of SMEs next to the SMEs Division, responsible for the design of policies and development strategies for the promotion and development of these economic entities.So ADEPME that its mission is to help promoters of SMEs to address constraints hindering their development so doing, it aims to "help strengthen the management capacity of SMEs and crafts, promote access to credit, training, advise and mentor entrepreneurs, to make proposals to improve legislation and regulation. "Furthermore, in order to provide "personalized" support to all entrepreneurs, according to the sector-based nature of their economic activities, the government has created new specialized agencies, including the Agency for the Promotion of Exports (ASEPEX).

5.4. The Diversification of the Company's Funding Sources

- In financing of entrepreneurship, there are now several options available to developers in relation with the amounts involved and their ability to meet the security requirements of financial institutions. Thus, to traditional bank financing, is now added micro-finance, leasing and private equity including venture capital.

5.4.1. Bank Financing

- At the end of 2010, there are 18 banks in Senegal and 3 financial institutions. Among the banks, 14 are general-purpose and 4 specialized, including 1 in Agriculture, 1 in Housing and 2 Microfinance. The dissociation between "commercial banks" and "development banks" tends to fade in favor of a universal bank that is interested in "everything." Nevertheless, it should be noted that if the financing of the operating cycle (working capital, salary advances, seasonal loans ...) of companies is supported by banks, investment coverage still faces the ongoing problem of real estate collateral and / or property and personal contributions of about 30% of the requested amount. This situation is taken up by the 2007 report of the WAMU Banking Commission (WAMU), which confirms that Senegal "banks grant more short-term loans with discount that occupy 4 8%, 18.8% overdraft and other short-term loans 31%, including advances on public procurement which occupies almost all. Long-term loans are low and represent 5% of loans to customers. They consist mainly of mortgages and cover more than 70% larger companies. SMEs are less than 20% of these credits, an envelope which is around 12.5 billion out of 64.5 billion across all businesses. "Ultimately, access to bank credit is more difficult to start a productive economic activity. This pitfall related to the nature of «generalist" banks give any legitimacy to the incessant recommendation of economic actors in Senegal to create venture capital firms and development banks or otherwise to use microfinance. Also, it should alleviate anxiety related to the reluctance of banks because "every good project finds funding."

5.4.2. Microfinance

- Microfinance institutions (MFIs), also called decentralized financial systems (SFD) are organizations that offer financial services to people excluded from the traditional financial system. Among MFI clients include, increasingly, "micro-entrepreneurs" (small traders, service providers, craftsmen, etc.) which generally operate in the informal or unorganized sector. Microfinance thus appears as an alternative to bank financing that proves unattainable with good fringe entrepreneurs unable to honor the personal contribution and warranty requirements. However, its development is limited by the relatively small amounts involved and the high interest rates (27% against a ceiling of 18% for banks). Attempts to modernize and structuring are fortunately addresed to give this area the whole place it has in the national economy.

5.4.3. Leasing

- According to the final report of "the study of supply and demand of funding of SME in Senegal t" September 30, 2009, sponsored by the SME Department, there are only two institutions specializing in leasing in Senegal: alios Finance, alios Finance Ivory Coast branch, and Locafrique. Incidentally, banks CBAO / Attijari and SATS (Societe Generale de Banques au Senegal) also offer similar services. Embryonic regulatory framework already exists for leasing. This means therefore that the low enthusiasm of entrepreneurs for this method of financing is as much to his ignorance and the complexity of the implementation of such a partnership. With this in mind, ADEPME initiated in March 2010 a forum to explain the characteristics of the lease.The meeting, which was attended by 1200 participants (companies, financial institutions, regional leasing companies ...) has not only to make known to the participants the mechanisms of leasing but also to inform the institutions financial companies' funding needs in this area.

5.5. The Business Environment

- The business environment is a key barometer to assess the possibilities of emergence and development of enterprises in a given country. The role of the state in improving the business environment is critical.In Senegal, the business environment is the subject of several recommendations to improve the attractiveness point of view of local and foreign investors. Among the authorities in this regard include the Presidential Council on Investment (CPI), which brings together around the President of the Republic, the national and foreign private sector as well as technical and financial partners. This means that the state plays the role of facilitator and "impartial" arbitrator in relation to the market in the promotion of entrepreneurial initiative strategy. Thus, since 1999, in partnership with the World Bank, the Government of Senegal has set up a Reflection Group on Competitiveness and Growth (GRCC) which generated a private sector development strategy, the key, priority action plan.If the implementation of the priority action plan has failed to remove all obstacles to the creation and development of enterprises, it still produced results corroborated by the Doing Business report of the World Bank in recent years. In 2011 alone, Senegal ranks 152nd out of 183 economies in the overall ranking on the ease of doing business.Thus, the establishment of a single window within the APIX has significantly reduced business creation time from 58 days to 48 hours. The procedures are facilitated by the Support Office to the Business Creation (ECB). Many other indicators used by Doing Business are subject to an easing of procedures, thereby reinforcing Senegal's competitiveness relative to its neighbors in the WAEMU. Thus, in the field of cross-border trade, Senegal is one of the most reformers in the world for the past five years the country, occupying the 67th place worldwide in 2011. As such, the importance of reforms in 2008 has made the most reformist countries in Africa, also occupying the 5th place worldwide.

6. Conclusions

- The Senegalese entrepreneurial context is undoubtedly the subject of a new situation marked by a clear consensus will to upgrade informal enterprises to become competitive entities internationally while preserving their entrepreneurial dynamism, source of job creation and social stability. This paradigm shift is particularly appropriate that the societal relation to the business has changed dramatically. To this is added the emergence of a class of wealthy entrepreneurs who are in all respects an inspiration for youth in search of role models. The business environment has also experienced major changes, especially since the advent of political alternation in 2000 and in 2012. Among the major events that have promoted greater visibility conditions for the emergence and development of the business, prominently a new support system and promotion of private initiative and a diversification of entrepreneurial funding sources that would benefit also to be strengthened to more closely match the needs expressed by economic operators.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML