-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(7): 448-458

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130307.16

Adapting the BSC for SMEs – Observations from an Action Research Study

Azman Hussin, Rushami Zien B Yusoff

College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 UUM Sintok, Kedah Darul Aman, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Azman Hussin, College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 UUM Sintok, Kedah Darul Aman, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper critically examines the use of the balanced scorecard (BSC) for small and medium enterprises (SME). Despite its popularity and utility for strategy management, the literature reporting on the uses and limitations of the BSC in SMEs is rare. The literature survey also highlighted some of the gaps and issues related to strategy and SMEs. The researchers used their experience in helping organizations of various sizes implement the BSC to formulate a simpler and more practical strategy implementation model for SMEs that adapts some key ideas of the BSC together with other strategy management ideas like building lasting organizations and strategic capabilities. The model was developed through an action research project with a Malaysian SME in the IT industry. It was also tested with another start-up non-profit organization. This paper describes some of the observations and lessons learned.

Keywords: Action research, Business strategy, Management research, Innovation, Balanced scorecard, SME, Capabilities

Cite this paper: Azman Hussin, Rushami Zien B Yusoff, Adapting the BSC for SMEs – Observations from an Action Research Study, Management, Vol. 3 No. 7, 2013, pp. 448-458. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130307.16.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- This paper presents part of an ongoing action research to explore the integration of some new management ideas related to design thinking[1-4] with relatively established ideas and tools in strategy management like core competencies[5], customer value propositions[6] and the balanced scorecard (BSC)[7-14]. Of particular interest is how to apply the integration of these ideas to small and medium sized companies (SME) that acknowledge their need to formulate and implement some form of strategy in moving forward. Methodological research at the intersection of these management ideas could contribute to new knowledge in terms of practical case studies or even perhaps a simple framework related to strategy management for SMEs.We firstly review the issues related to strategy and SMEs to know what improvements are needed. We then critically examined the BSC as a relevant and popular framework for strategy implementation and business performance management. It is well documented and is among the top ten globally used management tools[15]. Starting from such a best practice framework we describe how it can be adapted to address some of issues related to strategy and SMEs. We then propose a simpler and more practical strategy visual template for SMEs.

2. SME and Strategy Management

- Singh, Garg and Deshmukh reviewed about 134 research papers, mainly from referred international journals, and specifically concluded that for SMEs to be more competitive they need to develop and implement strategy successfully [16]. This review highlighted some issues related to strategy and SMEs:• Empirical research on strategy development by SMEs for competitiveness is lacking. Even in developed countries, most of the studies related to competitiveness have been devoted to large-scale enterprises (LSEs). Most of the researchers have not tried to analyse the difficulties and constraints of SMEs under the new globalized and liberalized economy.• SMEs have not given due attention for developing their effective strategies in the past. Most of the strategies have been formulated for short-term goals as most of them are localized in their function.• SMEs are also not following any comprehensive framework for developing their strategies and quantifying their competitiveness.Small firms with active strategic planning and communication are expected to out-perform those without, with many of the formal techniques associated with the process, being key concerns. Other issues compound the complexity of strategy management in SMEs. For example, SMEs are typically subjected to external pressures from both suppliers and their large customers that sometimes deny the opportunity for the strategy formulation and formal planning techniques that are undertaken in large organizations. Resources, both financial and managerial, are often simply limited in the SME[17].Because of both their resource demands and their perceived rigidity, coming out with a broad set of formal planning documents is not expected to be positively associated with organizational performance in SMEs[18]. The crucial need to adapt and meet external demands lessens the need to state a small company’s plans in minute detail at any single point in time. However, statements of purpose or vision, sufficiently adapted for the use of small companies, have been connected to success. Written mission, values and vision statement is positively associated with organizational performance of SMEs[19]. Strategy is expected to guide the successful SME, with informality as a distinctive characteristic, in contrast to the large organization[17]. Only general guiding instruments, like mission statements, and operational documents like short-term, written project plans should therefore offer SME managers more traction in dealing with their strategy implementation.SME success is generally attributed to the managerial skills, training and education, and the personal background of the SME’s leader(s)[20]. The drive to invest in new improvement programs is influenced mainly by senior management, regardless of firm size[10].A comprehensive literature review covering 6,618 papers in the field of performance measurement and management for SMEs and large companies to propose a research agenda for the future, confirmed that many management frameworks are designed for large companies and do not address the particular constraints and needs of SMEs like lack of resources and the need to be dynamic and agile[21]. They showed that specific management frameworks for SMEs are lacking and thus become open areas for research.

2.1. Strategy Management must be Simple for SMEs

- Strategy is important for SMEs but the methods to develop and implement strategies must consider the limitations that SMEs face. The wholesale adoption of many valid strategy methodologies designed for LSEs will probably not work for SMEs. Based on our experience, we find that strategy development and implementation following the many different documented approaches and methodologies mentioned in strategy books and academic papers are time-consuming, resource sapping, costly and restrictive. But the most negative drawback is that these methods do not lead to simple and quick implementations. This last factor is particularly significant in the fast-paced networked economy we are in today. Eisenhardt and Sull argued that when the business landscape was simple, companies could afford to have complex strategies. But now that business is so complex, companies need to simplify. They proposed strategy as a unique set of strategically significant processes and the handful of simple rules that guide them[22]. This confirms that the search for simpler, less costly and more action-oriented strategy management approaches is of interest to not only businesses and strategy practitioners, but also academics. Collins has proposed similar simple approaches like the hedgehog concept[23] and more recently the SMaC concept[24]. These approaches advocate companies to focus on selected processes and build core competencies to excel in the execution of current businesses while positioning them to capture unanticipated and fleeting opportunities that are becoming the norm in our current fast-paced networked economy. The processes might include product innovation, partnering, spinout creation, or new-market entry. Eisenhardt and Sull maintained that their proposed “strategy as simple rules” is closer to the way “entrepreneurs and underdogs seize opportunities in the here and now with a handful of rules and a few key processes.”The predominant expression of strategy for SMEs is through activity rather than conception[17]. Thus many of the existing popular strategy development methods may not be useful to the SMEs due to its resource demands and also the time taken before the strategy can be acted upon in terms of activities. From this overview of strategy and SMEs, we highlight some important elements in developing a strategy framework for SMEs.• simplicity• resource constraint time, people and skills• costs to implement• leadership role to set mission, values, vision• culture and values• leverage on competencies for greater value• actionable• informality in documentation and reviewsThis research plans to address some of the issues discussed and summarized above by proposing a simple but comprehensive framework for SMEs to develop and quickly implement their strategies. This framework will be developed and documented through action research involving a singular case company, The Firm.

3. Overview of the Balanced Scorecard

- The original papers that presented the research work on the BSC clearly showed the central role of measures[7-8]. It was first proposed as a much improved and more effective organizational performance measurement system (PMS). Although the BSC concepts are now being presented as part of a broader strategy execution framework[13], measures still form a central emphasis of the BSC when its creators promoted the importance of linking business analytics and operational scorecards to the BSC[14].

3.1. BSC Criticisms

- The BSC remains a relevant and popular framework for strategy implementation and business performance management. It is well documented and is among the top ten globally used management tool[11]. However, it has its fair share of criticisms against some of its concepts and the many problems related to its implementation.Some of the early comments by researchers have criticized its concept[26-34]. They have shown that it:• fails to identify performance measurements as a two-way process, since it focuses only on top-down performance measurement.• is unable to answer the question of what one’s competitors are doing.• is rigid and limited to customers, and ignores other parts of the company, such as the employees, suppliers, alliance partners and the local community, i.e. it does not consider the extended value chain. It does not adequately highlight the contributions that employees and suppliers make to help the company achieve its objectives. The role of the community in defining the environment within which the company works is also not made prominent.Some of these criticisms are addressed in the later works of Kaplan and Norton[11-13], particularly on the role of the employees for which some detailed framework on human capital has been proposed. The role of the community has also been addressed in a general way through the emphasis of managing regulatory and social processes as part of the generic strategy map template[11]. If the role of external influencers like competitors, suppliers and alliance partners is deemed strategic to a company, an additional perspective can be incorporated in the company’s strategy map[11], indicating that the BSC concept can be adapted to include components that may not appear in the standard generic BSC framework while maintaining consistency with its underlying concepts.Marr et al. criticized that the Learning and Growth perspective, which is where the non-process related factors for innovation like culture and skills are supposedly addressed, is the weakest link in the BSC[35]. Speckbacher et al. discovered that over 30% of the BSC users covered in their study have no Learning and Growth perspective[36].Norreklit argued that the general causality logic of the BSC and strategy maps by implication is flawed[33]. Marr and Schiuma commented that the focus on how intangible assets influence business processes in the BSC causality model is said to exclude a consideration of interdependencies between the intangible assets themselves. Also, the BSC model does not address the interdependencies between the resources within the company[37]. The researchers have gone through many practical projects on developing the BSC and have experienced customers’ facing difficulties in really relating the objectives and measures under the Learning and Growth perspective to the objectives in the other perspectives. The generic concept seems easy but working out the details for a specific case is challenging.The most scathing attack on the BSC is probably the work done by Voelpel et. al., arguing against its usefulness for the innovation economy. They claimed that[38]• the four perspectives of the BSC are mainly focused on a single organization and do not take the activities of the related industry sector into account. • the static nature of the BSC tends to struggle with the challenges of a competitive and changing business world. • the external innovative connectivity of an organization is hindered by the BSC, which is mostly an internal document. • the predominant mindset connected to the application of the BSC is process oriented and linear, making it difficult to deal with an interconnected and networked world. • the BSC process may be relatively rigid since the cause-and-effect relationship tends to limit strategy planners to think along the four perspectives. Those that do not fit, or cannot be categorized, within the given framework of the four perspectives are in danger of being uncared for.Many of these conceptual criticisms have their merits. The BSC was developed from a multi-company study[38] and the subsequent follow-up work also used case studies. It is not easy to model a complete framework for strategy management and implementation based only on case studies and postulate that the model can be relevant to all organizations. It is obvious that adjustments and adaptations must be made when the BSC is being implemented for a particular organization within a specific industry. There are many other issues related to the implementation of BSC. Bourne et al. collated and categorized these implementation issues as context related, process related, content related and project specific implementation factors[39-40]. Other implementation barriers include difficulties in evaluating the relative importance of measures and the targeted problems and in decomposing goals for lower levels of the organization[31].Kaplan and Norton acknowledged two sources that lead to the failure of the BSC in large companies: the design and the process[10]. Design failures include:• too few measures in each perspective, leading to failure to obtain a balance between lead and lag measures or financial and non-financial measures.• too many measures without identifying the critical few: in this case, the organization will lose focus and be unable to find the relationship between measures.• failure of measures selected to depict the organization’s strategy. This happens when an organization tries to input all its measures into each perspective without screening to select only those measures linked to its strategy.Process failures are the most common causes of failure of the BSC and include ([10], p. 361):• Lack of leadership commitment• Too few individuals involved• Keeping the scorecard at the top• Overly long development process• Treating the BSC as a one-time project• Treating the BSC as an IT systems project• Hiring inexperienced consultants• Introducing the BSC only for compensation.From the literature, it appears that the application of the BSC as a full-fledged strategic management system would take approximately 25 to 26 months to progress from clarifying the vision to the point at which individual performance is linked to the BSC[10]. Bourne et al. mentioned that in their study of successful implementations of the BSC, it took between 15 to 26 weeks to design and develop the measures and a further 9 to 13 months for the implementation[40]. The rather long development period can probably be phased to allow for partial implementation, but the process does require significant time. This is a major shortcoming of the BSC for companies in fast moving industries and those that need to make dynamic adjustments to their plans and strategies. The time and effort required to go through the processes may seem daunting particularly for SMEs.Bourne et al. suggested that some problems are simply hurdles to implementation rather than factors that completely stop the project[40].

3.1.1. BSC Criticisms: Measures

- It is interesting to note that some of the criticisms against the BSC that appear in the academic literature are related to measures. In reviewing the full list BSC of implementation related issues[39,40], the majority of the items are process and measurement content issues; the very issues that the BSC, as a performance measurement system, is specifically developed to address. These include the problem of large number of measures diluting its overall impact, measures being too poorly defined and the need to quantify results in areas that are more qualitative in nature.Kaplan and Norton proposed the BSC to improve strategy implementation and to promote strategic alignment and communication within organizations through a more balanced and comprehensive PMS[7-9]. However, in a recent publication Micheli et al. quoted several scholars claiming that a clear articulation of strategy through the use of a PMS, by translating strategy into a set of measures, is not necessarily beneficial. It could lead to organizational inertia and limit flexibility[41], and even hinder change within organizations[42]. Johnston and Pongatichat have identified several potential tensions between strategy and measurement, not least because the design of PMS requires management commitment, time and effort, which are not always available[43]. The appropriate use and review of performance measures and targets helps promote both single- and double-loop learning that favour continuous improvement and organizational adaptation to the business environment ([9],[13],[44]). However, what is perhaps more important is the qualitative learning for continuous improvement and organizational adaptation to the dynamic business environment. Measures can help to promote this learning but may not be crucially important in articulating and implementing strategy. These observations from the literature suggest a bold proposition that one can do without the need of a rigorous measurement system in developing and implementing strategy. This will remove many of the measurement related issues that were mentioned earlier, reduce the time and effort in strategy development and implementation and generally simplify the related processes.

3.2. BSC and SMEs

- Literature reporting on the uses and limitations of the BSC in SMEs is rare[45]. At the same time, the BSC is believed to be as beneficial for SMEs as it is to large organizations[10]. However, there are very few studies that reveal the limitations of its application in SMEs, which may be due to the limited application of this method in SMEs.Since the BSC is an example of a performance management system (PMS), factors that can be obstacles to PMS implementation in SMEs may apply to BSC implementation in SMEs. Rompho mentioned that these factors include limited human resources, limited financial resources, lack of supporting software, lack of strategies resulting in short-term orientation, and no formalization of the processes[45].In a more specific study of PMS for SMEs, Cocca and Alberti identified the main shortcomings of the PMS currently used by SMEs, and provided an overview of the evolutionary path of PMS in SMEs[46]. The results of the survey showed that the main weaknesses of PMSs in SMEs concern the scope of measurement and data collection and storage. In fact SMEs seem to suffer from lack of data apart from financial data and from the lack of satisfactory IT infrastructure. Other difficulties in managing the PMS are related to the communication and use of performance measures. Furthermore poor quality of the performance measurement processes has been highlighted. Again this study substantiates the problems and difficulties of relying on measures to improve the performance of SMEs.The above findings from the literature and its analysis suggest that in developing a simpler approach for strategy management and SMEs, the role of measures need to be critically examined since it cannot be easily implemented within SMEs. Clearly there are problems in implementing the measures portion of BSC and other measurement systems even in large organizations. The related problems are even more acute for SMEs. The researchers suggest a bold proposition that one can do without the need of a rigorous measurement system in developing and implementing strategy. Simplifying the measures to obvious outcome measures only will remove many of the measurement related issues that were mentioned earlier, reduce the time and effort in strategy development and implementation and generally simplify the strategy management process for SMEs. Obviously the trade-off will be limited quantitative data in monitoring the progress of the strategy implementation.

3.3. BSC Evolution and Adaptation

- The BSC has come a long way since its introduction[7] and despite its fair share of criticisms and negative remarks it is one of the more popular and widely used management tools[15]. The researcher believes that the continued evolution of the BSC concept and its adaptability through different and varied application cases ensures its continued relevance. It started as an improved performance measurement tool and used as a measurement framework for strategy implementation. The BSC was then proposed as a strategy management framework through the five principles of the Strategy Focused Organization (SFO)[10]. The details of the SFO occupied most of the work by the original authors until today[11-13].Other researchers also commented on the different definitions of the stages of the evolution of BSC ([36],[47-50]). The first generation BSC appeared in the early 1990s and combined financial and non-financial indicators with the four perspectives (financial, customer, internal business process and learning and growth). At this stage, measurement systems without cause–and-effect logic may also qualify as Balanced Scorecards as long as they show a balance of measures across different perspectives.The second generation BSC appeared in the mid 1990s and has put some emphasis on cause-and-effect relationships between strategic objectives and between measures ([36],[49-50]). Morisawa[47] and Miyake[48] proposed the view that the key contribution of second-generation BSC was the formal linkage of strategic management with performance management, similar to integrating the BSC as a strategic measurement system to the other principles of the SFO[10]. It became a strategic management tool, usually making use of a strategy map to illustrate the linkage between the various strategic objectives and measures.The third generation BSC appeared in the late 1990s. The third generation BSC is about developing strategic control systems by incorporating destination statements and optionally two perspective strategic linkage models. It uses only two “activity” and “outcome” perspectives instead of the traditional four perspectives[50]. Others suggested that the third generation BSC is the second generation BSC containing action plans/targets and linked to incentives[36].Field[51] presented an interesting strategy map of a case study reported recently in a publication edited by the BSC creators. It seems to tacitly approve an unconventional strategy map that eliminated the four conventional perspectives. It shows that the number and category of perspectives and also the components of the strategy map are adaptable within the BSC framework. It is clear than that the core principle of BSC remains balance. In the process of applying the BSC, organizations seek for balance and harmony between objectives, measures and projects that are long-term and short-term, financial and non-financial, factors that affect the individual and organization, internal and external factors, causes-and effects, and results or outcomes and the activities or drivers that lead to the outcomes.

4. Research Question

- An initial literature survey was undertaken to establish the status of current knowledge in the area of strategy management for SMEs. This survey revealed that while there has been increased attention on strategy management per se, current literature is inadequate in respect of the specific SME context. This leads to the main research question as how to develop and formulate a simpler and more practical approach for strategy development and implementation for SMEs that integrates the BSC while incorporating features that address some of the issues related to strategy, the BSC and SMEs ([16],[45]).Also this research will add to the limited studies on BSC and SMEs[45].

4.1. Research Methodology

- This research combines the analysis of the literature that relates to SMEs and strategy, the BSC and SMEs and the combined practical experience of the researchers in implementing the BSC to develop a simpler strategy framework for SMEs. The Action Research (AR) methodology was used to develop and test the framework with the case company. AR is a member of the case-study family of methodologies[52]. The unique element of AR that differentiates it from other forms of case study is the participation of the researcher.The action research (AR) case study involves The Firm, a singular medium sized Malaysian company in the ICT industry with about 150 employees. It has been in business for slightly less than 20 years and has some experience in applying some strategy management concepts and tools like customer value propositions and the BSC. The Firm realizes that in going forward it must have stronger innovation and strategy management capabilities to implement strategies that can differentiate it from other companies within the industry and also provide it with more sustainable competitive advantage.French provided a recent comprehensive review of AR for management research and showed its use through a series of articles related to strategy and SMEs[54-58]. Daniel and Wilson suggested that AR provides a methodology that is well suited to dynamic or turbulent or fast-changing environments using the example of e-commerce[59]. They said that AR places an emphasis on the immediacy of outcome and recognized that in turbulent domains, the limited practical experience of the field may rest primarily with practitioners rather than academics. This research involves an SME in the ICT industry that is clearly dynamic and thus justifying the use of AR.As mentioned earlier, literature on the BSC and SMEs is limited. Thus an appropriate choice is to research the problem in action and be engaged in the process both as a facilitator/researcher and participant. The main researcher was engaged at different levels of participation as a facilitator, participant and, at times, a mere observer. These have all the elements of emancipatory AR[60].The researchers prefer both the simplicity and flexibility of the original phases or stages of AR as presented in a recent work on AR applied to e-commerce[59]. These stages will be used in this research. The AR documentation model[52-54] provided more structure and details to help the researcher follow a more thorough thought process and was most helpful in taking notes and writing up on this research. This led us to combine both in a simple table with the inputs given in bullet lists as a guide (see Table 1). The documentation model covers three components before the action and another three after the action, as shown in Table 1. The ‘why’ questions before the action help the researcher identify the expectations and assumptions. Comparing plans to reality then helps identify which of those assumptions and expectations were incorrect and need to be improved, and that is the ‘something learned’.The reflective or learning stage is the heart of AR[52]. It is supposed to provide the researcher with important insights with which to move the process forward. This stage includes the data analysis. The researcher is the sole arbiter of the analysis but must be aware and take steps to include the interpretation of others. Reflection of the action recorded during observation is usually aided by discussion among the participants. Group reflection can lead to a critical review of the meaning of the social situation and provides a basis for further planning of critically informed action, thereby continuing the cycle[54].

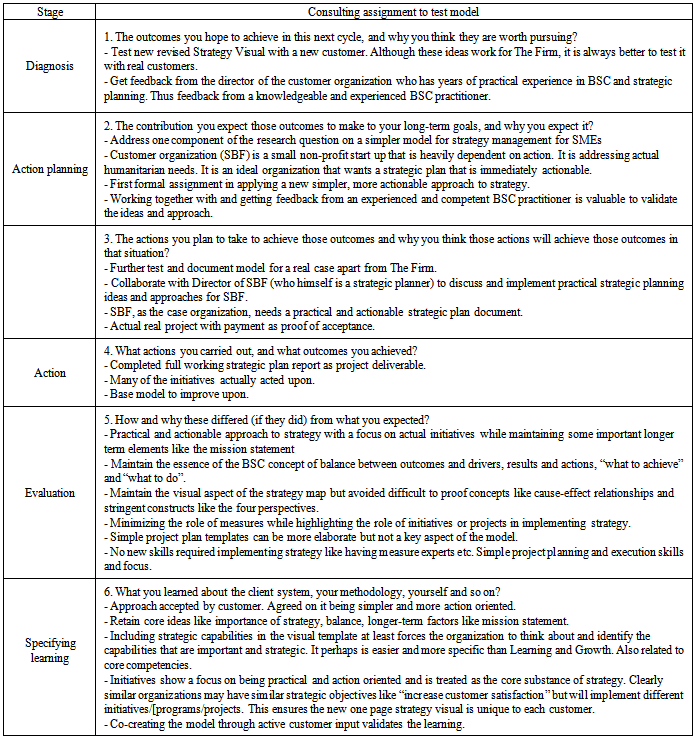

|

4.2. Developing the Model

- Developing the model actually involved many minor AR cycles of diagnosis, planning, action, evaluation and specifying learning. It involved combining learning from the experiences of the researchers and also The Firm in implementing the BSC. The small changes were tested and adjusted. The following steps summarize the main ideas.1. We started with the classical BSC strategy map model and components as summarized in Figure 1. As mentioned earlier the BSC is well documented and is among the top ten globally used management tools. Thus we are not starting from scratch to develop the model but from a best practice framework.2. The first simplification we made was to emphasize the focus on “initiatives” instead of the focus on “measures” as in the original BSC model. Initiatives are key action programs or projects required to achieve the longer-term targets associated with each measure that is related to the particular objectives. One of the example objectives in Figure 1 is to improve the project management maturity of The Firm for which the stated measure is the percentage of decisions made during the project review sessions that are implemented on time. If the current performance level is say 50% and the desired future target is 90%, The Firm must implement an intervention program to close the performance gap. The example quotes two programs that can help it achieve the higher target; increasing the number of project managers with Project Management Professional certification and to establish a Project Management Center of Excellence. As such, initiatives are related to the measures and targets that are in turn related to the specific strategic objectives. In reality, some initiatives may be also related to other objectives. There must then be a direct cause and effect relationship between the objectives and initiatives. The arrow at the bottom of Figure 1 proposes a vital observation by the researchers after many years of experience in implementing the BSC. Measures describe the objectives quantitatively but strategic initiatives are the real drivers of action that help achieve the objectives. Thus one practically manages strategy by managing initiatives. One can implement strategy by mainly monitoring the implementation of the related causal strategic initiatives. This will greatly simplify strategy implementation and make strategy actionable since initiatives are tangible programs and projects. It also reduces the time, resources and costs involved in strategy implementation since developing measures and actually producing the quantitative reports do take significant effort. There are other criticisms related to measures that were discussed earlier. One of the problems to be addressed in this research is to overcome some known issues in managing strategy for SMEs. This observation that managing strategy is essentially managing action programs and projects forms a significant conceptual contribution to the proposed strategy framework.

| Figure 1. Key components of the classical BSC framework |

| Figure 2. New strategy visual |

4.3. AR Cycle to Test the Model

- This section summarizes the next main AR cycle to test the model with an international customer organization. The summary exemplifies the use of a combined version of the documentation model[52-54] and the presentation format by Daniel and Wilson[59]. Although it is in point form it shows the benefits of starting the documentation as early as possible. AR promotes learning by doing or action and the learning only becomes explicit through actual documentation. We view that the real stuff in AR is in the last guiding question; ‘Specifying learning - What you learned about the client system, your methodology, yourself and so on?’ Dick emphasized this final point as the heart of the research component of AR, representing the growing understanding and it is probably from this learning that the contribution to knowledge will arise[52].

4.4. Data Analysis

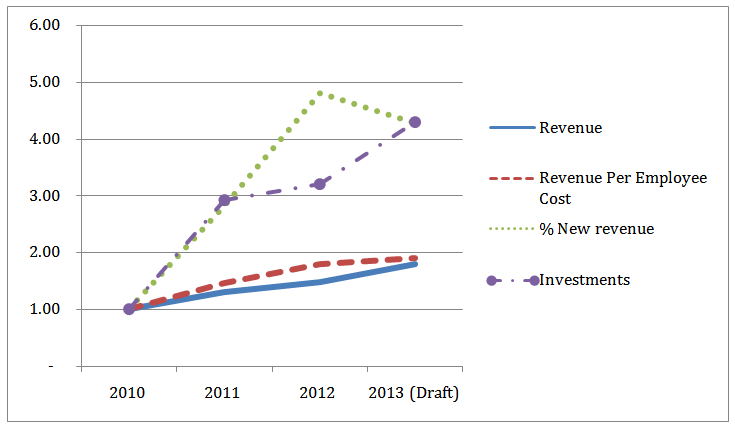

- Qualitative data analysis occurs during the reflective stage of the AR cycle. The reflective stage has the purpose of providing us with important insights with which to move the process forward. We were aware and took steps to include the interpretation of others and insights elicited through discussion or through the deliberation of participants. This is vitally important because they may provide insights that are not obvious to the lone researcher.Obviously the best test of any strategy implementation model is the success in achieving the stated outcomes of the strategy. Figure 1 shows some strategic financial outcomes for The Firm. The following quantitative measures were extracted from the financial performance data of The Firm 1. Revenue.2. Revenue per Employee Cost is a good productivity measure. The improved capabilities in project management, innovation and strategy implementation should lead to increase in productivity.3. % new revenue, as a simple outcome measure for innovation.4. Asset value of investments, as a simple measure of the increased investment efforts.It is important to keep the measures simple and the sources of data easily available[46]. Since SMEs suffer from lack of resources, the measures should be simple and easily collectable, otherwise the effort needed for measuring would be higher than the benefit gained. Similarly also the procedures for measures collection should be well defined and resource effective. Moreover it would be better to use only a few vital measures, reported in a graphically and visually effective way, in order to enable the manager to focus only on key performance factors and quickly take informed decisions[46].

4.5. Results and Discussions

- Figure 3 clearly confirms that The Firm greatly improved its financial performance while implementing its new innovation based strategy using the simpler and more practical model adapted from the BSC. The Firm achieved its revenue target of the strategic plan of MYR 50 million as shown in Figure 2. This was the main outcome measure related to the strategy. The innovation change agenda also significantly improved the employee productivity of The Firm with the “revenue per employee cost” almost doubled. The revenue from new products and services increased by more than a factor of four, providing conclusive proof that the innovation growth agenda was successfully implemented.The results confirm the general findings on the improved performance of SMEs with active strategic planning[16-17].The results also confirm that building strategic capabilities specifically help improve company performance consistent with the view that one of the most effective means of achieving competitive advantage is by using the firm's competencies or capabilities[5]. The results also confirm that SMEs can successfully identify and develop strategic capabilities that include generic capabilities like project management, innovation, strategy management and other specific technical capabilities.

| Figure 3. Financial performance data relative to the starting year of the new strategic change agenda |

5. Conclusions

- This paper has shown the successful adaptation of ideas borrowed from the BSC to develop a simpler and more action-oriented approach to help an SME implement strategy. The adaptations are based upon observations made from the literature review and also the experiences of the researchers in business strategy and the BSC. The key idea is to highlight the central role of strategic initiatives that shows a focus on being practical and action oriented and is treated as the core substance of strategy. Many organizations may have similar generic strategic objectives like “increase customer satisfaction” but will implement different initiatives to achieve the same generic objective. This ensures the new one page strategy visual is unique to each customer. This strategy visual also incorporates other best practice strategy management ideas like building lasting organizations and strategic capabilities that are useful for the SMEs.The role of measures is reduced to simple outcome measures that can be easily obtained in consideration of the known problems that SMEs face on data collection[46]. Apart from the strategy visual only simple project templates and plans for the strategic initiatives are required as practical documentation.This simple adaptation of the BSC framework addresses some of the issues summarized at the end of Section 2.1. The researchers are now working to improve and integrate this simple framework on strategy management for SMEs with some design thinking[1-4] practices.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML