-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(7): 333-340

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130307.02

Cognitive Individual Distortions and Emotional Factors: An Introduction to a Cognitive Approach to Governance of the Firm

Nicola Miglietta , Enrico Battisti

Department of Management, University of Turin, School of Management and Economics, Turin, Italy

Correspondence to: Enrico Battisti , Department of Management, University of Turin, School of Management and Economics, Turin, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The goal of this paper is the introduction of a cognitive approach to governance of the firm. There are a lot of relationships that tie the cognitive science to management and are founded on the role of the individual in the process of business management. Frequently, managerial decisions are taken using regular way of happening that are not fully rational but that are the result of cognitive distortions or emotional factors (positive or negative) which may push manager to make systematic errors. Starting from the cognitive distortion derived from the behavioral finance this paper describes some emotional factors, derived from the study of psychology literature, that can influence an individual during its decision making process. In this sense, we have identified the most common bias that can shove individuals, and therefore the manager, to take decisions influenced by cognitive distortions or emotional factors. At the end, after the introduction of a role of cognitive distortions in governance of the firm, we introduced a cognitive approach, with the objective of increasing the degree of knowledge of the effectiveness of its actions.

Keywords: Emotional factors, Decision making process, Cognitive approach, Governance of the firm

Cite this paper: Nicola Miglietta , Enrico Battisti , Cognitive Individual Distortions and Emotional Factors: An Introduction to a Cognitive Approach to Governance of the Firm, Management, Vol. 3 No. 7, 2013, pp. 333-340. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130307.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Empirical evidences prove that the irrationality, peculiar to each individual, represents a key trait of human action and, in particular, of the decision making process[1],[2], [3],[4].Much more often than you might imagine, managerial decisions are made using behavioural patterns that are not fully rational but are the result of cognitive distortions, which may push managers to make systematic mistakes[5], [6].Irrationality and the consequences of these distorted behaviours, with referrals to enterprise management, are not explained by expected utility theory and, in the financial field, are usually considered as anomalies[7]. However, these phenomena towards which the scientific community shows more and more interest, are studied by behavioural finance[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[13], and based on the interactions among cognitive sciences and decision making models. Even if different definitions of behavioural finance exist in literature, there is significant agreement between them. In particular, for Lintner, behavioural finance is “the study of how humans interpret and act on information to make informed investment decisions”[8]. Olsen asserts that “behavioural finance does not try to define rational behaviour or label decision making as biased or faulty; it seeks to understand and predict systematic financial market implications of psychological decision processes”[9].Assuming that the explicit behavior is the only scientifically analysis frequently done by psychology, behavioral finance took inspiration and demonstrated how emotional factors can influence the investment decisions of individuals[5],[6]; they do not always behave rationally, as postulated by the theory of efficient markets, but rather in breach of the classical theory of expected utility and straining to follow a prospect theory that assumes that individuals seek to obtain the best for itself. The prospect theory divides two phases in the choice process: an early phase of editing, which consists of a preliminary analysis of the offered prospects, and a subsequent phase of evaluation, where the prospect of highest value is chosen[6]. According to behavioural finance and prospect theory, individuals would be characterized by cognitive distortions, such as biases, heuristics and framing effects, in all phases that characterize their decision making process[3]. For this assumption, emotional factors and cognitive distortions that characterize an individual can be applied to governance of the firm.The use of a cognitive and systemic approach to the study of management[14] and governance of the firm represents a new interpretative key of the evidence emerged from the research, absolutely innovative and recommended for future developments on the subject.

2. Individuals and Cognitive Distortions

- A lot of classical economists have investigated the relationships between economic and cognitive sciences. For example, Smith, Marshall, Pigou, Fischer and Keynes studied the psychological foundations of preferences and beliefs[15]. Starting from these considerations, two scientific contributions can be considered, in a context focalized on modeling the complete rationality for economic agents, as the main theoretical premises to behavioral finance. These are the works by Kahneman and Tversky[5],[6], respectively about heuristics and preferences and the so called prospect theory, a new alternative theory to that of expected utility, theoretical basis for the study of human decisions, developed in the ‘40s by John Von Neumann and Oskar Morgentern. The expected utility theory assumed the presence of optimizing behavior and rational decision-making, but it did not consider some important variables involved in the decision process such as, for instance, the evaluation of alternative choices, related to the complexity of the task, and the limits of individual’s cognitive resources[16]. However, the axioms on which the theory is based do not find empirical evidence[17].Starting from this observation, the prospect theory adopts an inductive-descriptive approach: the aim is to integrate the expected utility theory and provide a more accurate representation of decision-making behaviors[6]. Kahneman and Tversky’s works are soon followed by those by Richard Thaler[18]. The use of pre-established theoretical models based on full rationality should lead managers in decision-making process and should provide a perception of the risk of non-survival. In reality, managers or individuals, in general, use behavioral models which are not fully rational, subject to emotional factors that can have a greater or lesser influence on corporate governance and on decision-making process[4], [19]. Therefore, a set of predetermined models may be insufficient, or sometimes inadequate, to investigate the structured decision-making process[2].It’s necessary to introduce a cognitive approach, which allows considering also the existence of emotional factors that characterize the individual and, consequently, the management, in order to increase the knowledge of the entrepreneurial decision-making process[20].According to the theoretical framework of cognitive science[21], the cognitive distortions taking part in human behavior are divided into three categories[22],[10]: - Heuristics.- Biases. - Framing effects. The heuristics are a quick way to think, decide and evaluate, by means of which individuals can solve problems, give judgments, and take decisions when facing complex situations or incomplete information.The justification for their existence is founded on the assertion for which the human cognitive system is based on limited resources and, not being able to solve problems through pure algorithmic processes, uses heuristics as efficient strategies for simplifying decisions and problems [22],[23],[24].When the number and the regularity of information increase, the brain tries to find some “shortcuts”, allowing reducing the elaboration time, in order to take a decision anyway. These shortcuts are defined heuristics (or rules of thumb). They allow managing in a fast and selective way the information but they could bring to wrong or exceptionally simplified conclusions[25],[26].The main heuristics behaviors that can bring on errors in decision-making process are:- Heuristic Representativeness. - Heuristic Availability.- Heuristic Anchoring.- Heuristic Affect.The heuristic representativeness refers to the tendency of economic agents to make predictions, judgments and their choices on the basis of rules that use similarities or stereotypes[5]. The heuristic availability, represents a type of behavior potentially source of errors. It is summarized in the tendency, on the part of some individuals, to use the information that is more easily available than other which is to a lesser extent. Individuals tend to assign a probability to an event, based on the quantity and on the ease with which they remember the event happened in the past[27]. Therefore, they try to remember, or mentally generate, cases that are able to give them the favorable indications[28].This heuristic represents a behavior determined by the inadequacy of individuals to adapt to changes.It’s referred to the attitude of the individuals to stay anchored, when they have to face to an uncertain situation and decide, to a reference value, without properly updating their estimates[22]. It’s at the bases of conservative attitudes often adopted by economic agents[24].This heuristic represents the behavior of the individual who believes in his own capabilities and operates according to his intuition and instinct. Many individuals set up their choices and decisions on the basis of what, from an emotional point of view, make them feel better[29]. In this regard, a very important part of people's behavior is linked to the emotional aspect. By following emotions and instincts, sometimes more than logically reasoning, some individuals could decide to perform a decision in a risky situation, while not to perform it in other, apparently safer, ones[24]. Bias could be considered a systematic error and represents a form of distortion caused by the prejudice against a point of view or an ideology. The most common biases that can bring on errors in decision-making process are:- Overconfidence. - Excessive Optimism.- Confirmation Bias.- Control Illusion.Overconfidence, that seems to be a natural feature of human behavior, and excessive optimism are part of a wider state of mind in which the individual, in a given context, tends to overestimate his abilities and skills, which can determine irrational behaviors[8],[30],[31]. A mental process which consists in giving the most importance, among the information received, to those reflecting and confirming the personal believes and, vice versa, in ignoring or debiasing those negating inner convictions is called confirmation bias. This process could even lead an individual or a community to deny the obvious[32].In psychology we talk about perception or impression of controllability (illusion of control) in order to indicate the subjective feeling by an individual to have an influence on events. In this sense, some individuals believe that their personal involvement can influence the outcome of an event, which leads them to create an expectation of success often higher than the objective one[33].The framing effects are derived from the prospect theory, whose aim is to explain how and why the choices are systematically different from those predicted by the standard decision theory.Its theoretical foundation can be interpreted as a synthetic representation of the most significant anomalies found in decisional processes under uncertainty.The analysis carried on by Kahneman and Tversky[6] highlights some behaviors seen as violations to the expected utility that they have defined “framing effects”.The main framing effects are aversion to loss and aversion to certain loss that lead individuals to prefer safer operations, with a low degree of risk, even if with a lower value than others whose degree of risk is higher[34].

3. Individuals and Emotional Factors

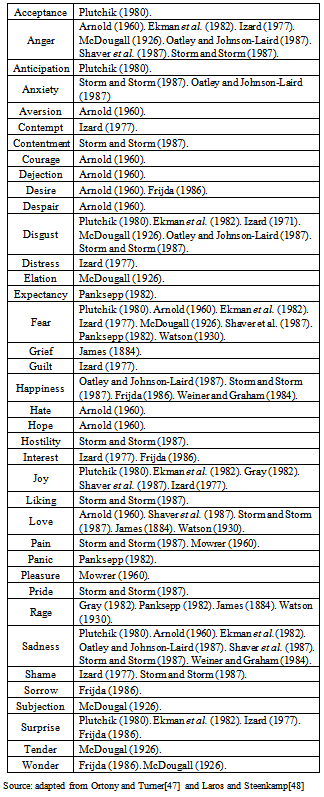

- A key role in decision-making processes of individuals is played by emotions that can have an influence on collective behavior. Despite the existence of a wide literature that highlights the effect of emotional factors on decision-making process and, in particular, on the economic decisions[29], we didn’t reach a universally shared classification of these factors[35]. Despite the number of scientific definitions proposed has grown to the point where counting seems quite without hope[36], a significant contribution in this way came from the field of psychology, when, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the psychologist John Watson[37], set out his thesis according to which each individual, when face up to a decision-making process, assumes a certain behavior that is affected by emotional factors.Emotions can be defined as mental and physiological states, associated with internal or external inducements which, in their turn, may be natural or learned[38],[39],[40], [41],[42],[43],[44],[45].

|

4. The Role of Cognitive Distortions and Emotional Factors in Governance of the Firm

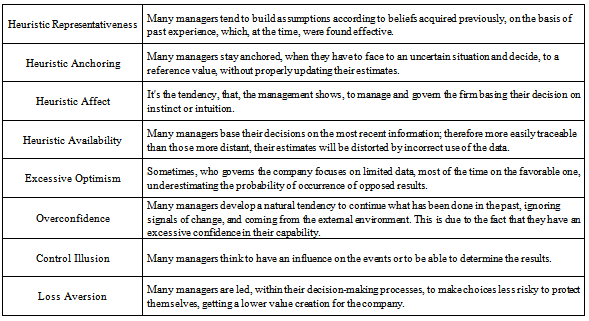

- The empirical evidences show that in reality individuals, in general, and manager, in particular, use behavioral models that are not fully rational, subjected to cognitive biases and emotional factors, that may have a more or less marked influence on the decision-making process and, more generally, on governance of the firm[53],[28]. We start our analysis from considering the effects of psychological biases on corporate decisions. The main cognitive distortions that affect the management have been contextualized within the analysis of the Behavioral Governance of the firm, which analyzed the negative effects that the lack of understanding and regulation of cognitive distortions may cause into enterprise system, taking into account the behavioral circumstances that lead to value destruction and to a loss of competitive advantage[20]. Among the psychological phenomena that influence the decision-making process of the individual, systematized by behavioral finance, those who mainly appear to have an impact on the process of governance are those summarized in the following table (table 2).

|

5. Conclusions

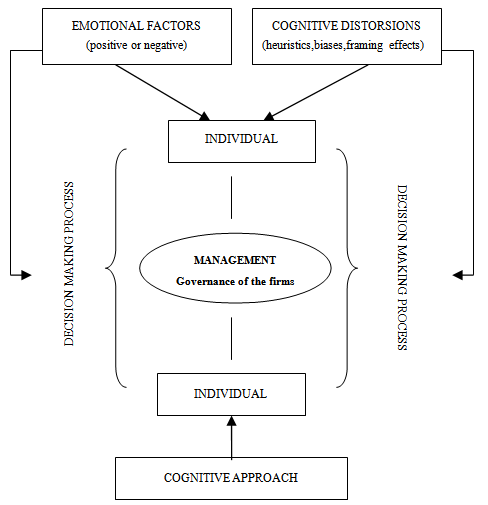

- The cognitive approach has as its main aim, the interpretation of the firm’s evolutionary dynamics, through the analysis of the individual and emotional factors that characterize the decision-making process.The systemic approach, which considers firm as a vital system that interacts with its over and under reference systems[55], is interested in studying its evolutionary dynamics by analyzing relations of consonance and resonance between the government body (management) and the environment, highlighting the importance of the management role that, on the basis of its skills, expertise and past experience, must be deduced from the constantly changing environment, the relational rules and opportunities which are supplied from the outside[56].Therefore, it follows that the government body is the core of the decision making process. In theory, the use of pre-established models based on full rationality should direct managers throughout the decision-making process.In reality, managers use behavioral models that are not fully rational, subject to emotional factors that can have a greater or lesser degree on firm’s governance and on decision-making process.There is a complex dynamic between emotion and decision that highlights an influence of emotional factors both in the evaluation of the options of choice, and in the creation of a determined behavior[49].The cognitive approach is interested into investigating the relationship between emotions and strategic decisions that refer typically to decision-making processes and to the effectiveness of the governance of the firm (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. A cognitive approach to governance of the firms |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML