-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(6): 304-315

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130306.03

Corporate Governance: A Critical Comparison among International Theories, Codes of Best Practices, and Empirical Research

Alessandro Merendino

Department of Economics and Management, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, 44121, Italy

Correspondence to: Alessandro Merendino, Department of Economics and Management, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, 44121, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

As strong role played by the financial globalized market, several countries have adopted rules and principles (best practice codes) to be shared among all companies, in order to provide tools to solve governance problems, regulate relations among managers and shareholders. This paper seeks to investigate American, English, German, Japanese and Italian codes of conduct. Literature agrees that corporate governance archetypes are those Anglo-Saxon and German-Japanese; on the other hand the Italian model represents an interesting case study. These three models are based on different international theories (Agency, Stakeholder, Resource Dependence, and Stewardship). Scholars maintain that the Agency theory is the most valid of the theories, with respect to the existence of international convergence processes. Thus, the objective of the paper is twofold. First of all, we want to understand which international theory has been adopted by Anglo-Saxon, German-Japanese, and Italian codes. Secondly, we wish to verify whether empirical research confirms principle efficacy contained in codes of corporate governance. From a comparative study among international theories and rules it would emerge that variables contained in the codes would be better explained and regulated under Agency approach. It should be noted, however, that each country – in spite of the convergence processes towards a single standard of rules – is affected by their social, and economic background. Finally, we could argue that empirical studies do not often explain critical success factors in the same way of codes although both are the result of best practices.

Keywords: Corporate Governance, International Theories of Corporate Governance, Anglo-Saxon and European Codes of Best Practice, Empirical Research

Cite this paper: Alessandro Merendino, Corporate Governance: A Critical Comparison among International Theories, Codes of Best Practices, and Empirical Research, Management, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 304-315. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130306.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In the current economic scenario we are facing rapid worldwide change in the environmental conditions under which companies operate. Thus, firms should not be analyzed as isolated units outside the environment because they are born and grow within it[1]. Shareholders and managers should understand this and investigate problems and solutions in order to adapt to these changes[2]. This is fundamental to the aim of reaching, maintaining and improving economic equilibrium[3] over time: earnings must “pay” or cover the input costs and the cost of capital. The aim of economic equilibrium should reflect the capacity of the company to satisfy all the stakeholders’ expectations. This means that a lack of effective governance could damage the stakeholder’s interests, compromise the economic equilibrium goal and as a consequence hinder positive performances. Thus, in the current economic-financial context the board of directors has a crucial role, it must be able to adapt to the environment, maximizing firm management efficiency and efficacy[4]. For these reasons, corporate governance represents an important topic within management studies especially in these last years, characterized by the global financial crisis. Indeed, corporate governance research has been undertaken as a reaction to different factors, such as globalization, industrial colossus bankruptcy (Enron, WorldCom, Parmalat, Alitalia, etc.) and the economic-financial global crisis. The events that affected companies on one hand, disclosed firm government and management deficit and on the other hand fostered sharp criticism of boards of directors and managerial conduct[5]. In this complex, dynamic and uncertain context[6] the need and willingness to adopt common standards for companies arose in order to secure and control management[7]. These standards or principles are contained within codes of conduct or codes of corporate governance which have been gradually adopted by several countries; they describe strategies and behavior to adopt in the event of management problems[8] and they represent the so called best practice of all companies. Hence, these codes could represent a reinforcement of market efficiency, a strategic tool for management and board of directors[9] and a reference standard for shareholders and management as well as stakeholders. It is important to stress that corporate frauds and scandals have provoked a strong reform process, introducing accountability and transparency.This research focuses on the national and international literature of corporate governance and codes of best practice. On one hand, we study national and international literature, in particular corporate governance theories (agency theory, stakeholder theory, resource dependence theory and stewardship theory) and empirical studies conducted on Anglo-Saxon, the European (i.e. German-Japanese) and Italian companies samples. Literature[10] agrees on the fact that corporate governance models can be modeled on two archetypes: the Anglo-Saxon and the German-Japanese model. The Italian model is defined as the “mixed” one, a hybrid which means that while it shares some features of the above mentioned models it also differs in some ways[11],[12]. On the other hand, we study American, English, German, Japanese and Italian codes of corporate governance, because – as just reported – those countries represent two main international models of corporate governance and in addition the Italian one is an interesting case study. For these reasons, we wish to compare literature and codes of conduct, in particular we wish to study first of all, the connection between corporate governance international theories and the codes of best practice; secondly the relationship between the latter and empirical research on corporate governance. For this reason the objective of the paper is twofold, if the basis assumption is that international convergence international process is underway on corporate governance field. First of all, we investigate which theory is at the basis of corporate governance codes; secondly we verify if empirical studies accept or reject principles and rules contained in international codes.The paper is divided into five paragraphs, the following (second paragraph) highlights corporate governance international framework, in particular different approaches, company models as well as international theories. In the third paragraph, we will define the subject, the objective, the research questions and, the methodology; in the fourth the research results will be shown through a comparison map. In the concluding paragraph (the fifth) some reflections which briefly outline possible future developments of research are outlined.

2. Literature Review

- Corporate Governance is an eclectic issue but for the purpose of this paper the focus is on corporate governance research within management and business studies. Corporate Governance represents an international issue for academics, professionals, and companies because they are interested how to achieve good governance which could lead to good performance[13]The Literature review focuses briefly on corporate governance different approaches, international and national theoretical models and corporate governance theories.

2.1. Corporate Governance Approaches

- Ahrens, Filatotchev and Thomsen[14] reckon that ‘despite the enormous volume of research we still know very little about corporate governance’, probably because every firm has its own features it is unlikely that we will be able to generalize and define all corporate governance features. Huse[15] claims that ‘there is not one best design of corporate governance, but various designs are not equally good. Corporate governance designs will need to consider the context and the actors’.For this reason, it would be useful to describe different governance approaches, in particular two main approaches, i.e. the restricted and the extensive one. The former focuses attention on two main aspects: a) shareholders considered in this analysis perspective are the only company stakeholders; b) the existing conflict between property (shareholders) and control (managers). This point of view was defined in 1960 by Eells who used for the first time the word “corporate governance” to denote ‘the structure and the functioning of corporate policy’[16]. The latter argues that corporate policy is “a mixture of rules, organizations, habits and formal organs that aim to achieve the interests of the different stakeholders”[17] of the company. Solomon[18] claims that extensive approach (i.e. stakeholder view) is ‘the system of checks and balances, both internal and external to companies, which ensures that companies carry out their accountability to all their stakeholders and act in a socially responsible way in all areas of their business activity’.

2.2. Corporate Governance Models

- It is relevant to underline that every country has its own corporate governance system with different peculiarities because of the strong influence that rules, institutions and social regulation, developed and strengthened over time, have on the characteristics and on the function of company management mechanism[6]. Literature[10] agrees on the fact that corporate governance models can be modelled on two archetypes: the Anglo-Saxon and the European (or German-Japanese) ones. The Italian model is defined as the “mixed” one, the hybrid; this means that it has some features in common with the international models but at the same time differs in certain ways.[19],[20]. Anglo-Saxon countries adopt the so-called outsider system model, i.e. financial market rules can come between shareholders and management. Indeed, financial markets can regulate management and can develop value creation for shareholders which is the key to success in today's marketplace (i.e. «market for corporate control»[12]). The strong division of ownership that is peculiar to stocked companies on the ruled financial market[21] created a company similar to the Public Company characterized by a capital fraction. The German-Japanese model adopts the insider-system, known also as “relationship based” that is a network-oriented corporate system. In this case, the presence of financial markets has little influence whereas the financial intermediation that issues the risk capital is very influential. This model uses a bank-oriented perspective. In contrast to the Anglo-Saxon countries, firm institutional assets are characterized by a high degree of ownership concentration and the main shareholders are banks, family firms and internationals investors (the so called blockholders)[22]. Finally, the Italian model is not directly linked to other models. Widespread ownership companies (as seen in the outsider system) and financial intermediation inside the management (as seen in the insider system) do not exist[23]. Banks, then, do not invest in equity (or risk capital) but in credit capital: for this reason they do not interfere in firm management. Italian companies characterized by high ownership concentration are distinguished by a majority shareholder or a shareholders’ group linked by union agreements. The Italian model is characterized by the Latin insider system which is different from the German-Japanese insider system. The former considers the majority shareholders as the managers’ watchdog through the board; the latter considers the employees’ and bank’s high involvement in the control of the company[24].

2.3. Corporate Governance International Theories

- It relevant to highlight that there is a relationship between Anglo - Saxon, German-Japanese and Italian models and international theories corporate governance. Literature agrees that the agency theory[25],[26] and the stakeholder theory[27] are at the basis of the Anglo-Saxon model and the German-Japanese one, respectively. Regarding the Italian situation, literature is not so fecund in corporate governance theories. Yet, it is possible to observe that the Italian model, according to the contingency approach[28], is generally based on three different contrasting theories[29]: agency, stakeholders and resource dependence theories. The coexistence of the different perspectives is due to social - economic features that influence the national environment. These are the result of the existence of various interests and power balances marking out the company itself. Agency theory[25] mainly regards the conflict between the principal (shareholders) and the agent (managers). Whilst they pursue the same economic aim – to maximize their personal well - being – their interests are at odds. Stakeholder theory[27] - as opposed to agency theory, increases the analysis focus, i.e. it emphasizes the relevance of fulfilment of stakeholder’s interests. A firm cannot sacrifice all the stakeholders’ interests only to maximize the shareholders profit. Managers should negotiate, involve and coordinate all the people who have interests in a company. Resource dependence theory clarifies relationships between a firm and its environment. The assumptions are that firms cannot «produce all the resources they need to operate; therefore they must engage in exchanges with the external environment in order to acquire the resources they need to survive»[30]. In addition to forming relations with other stakeholders, managements should seek resources from outwith the network creation, in order to increase innovative development, this is fundamental for firms to be competitive. There is another fundamental corporate governance theory which should be considered stewardship theory. Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson[31] reckon that managers should be able to solve economic, social and sociological problems through contacts with other stakeholders in addition to forming relationships with shareholders. The Manager is a steward who is more likely than an agent to ‘value higher - order needs’. Authors [32] argue that people in organizations are ‘motivated by a need to achieve, to gain intrinsic satisfaction through successfully performing inherently challenging work, to exercise responsibility and authority’. It is relevant to notice that we are observing a convergence and standardization[33] process of corporate governance approaches and archetypes at international level. This is due to globalisation of financial markets, and an increasing reduction of discrepancies between spatial reference fields, cultures and information systems. Each System – Country, while maintaining its own features, is entering new territory that leads it to adopt characteristics typical of the Anglo - Saxon world, rather than an outsider system. Hansmann and Kraakman[34] proclaim ‘the triumph of the shareholder - centred ideology of corporate law among the business, government and legal elites’. In addition, Daily, Dalton and Cannella[35] argue that Agency theory has dominated corporate governance research, because it puts forward an adequate and valid explanation of problems connected with the separation between control and ownership, and governance model to solve interests conflicts. Market turbulence, globalization, technology, and structural changes provide a series of challenges for firms and their boards. The present research should be considered in this contextFor this reason, we point out some features peculiar to corporate governance Anglo-Saxon model, such as the board of directors (functions and dimension), other apical subjects (Chairperson, CEO), Committees (Audit, Nomination and Remuneration), considering the convergence processes mentioned above. This paper considers these variables coupled with English, American, German, Japanese and Italian codes of conduct, because – despite ongoing convergence processes – all corporate governance models remain valid and amply studied.

3. Object, Objective, Research Questions, Methodology

- This paper is part of a wider doctoral research project developed during a three year PhD. The project purpose is to analyse the relationship between corporate governance and economic performances of Italian and English companies. This research project adopts a methodological deductive - inductive approach[36] composed of three stages. The deductive phase is based on the critical analysis of national and international literature and empirical methods applied to Italian and English listed companies. The inductive phase consists in the empirical steps of the research in which the intention is to test the empirical methods. In the feedback phase, it is possible to understand the results after the models application verifying the skills related to the correlation of “governance-companies performances”. It will be possible to evaluate the need for future modified models which could offer more significant results, This paper represents the first step of in progress doctoral research.In particular, the paper object concerns the relation among national and international literature about corporate governance, codes of best practice of Anglo-Saxon, German - Japanese and Italian listed companies and empirical research. Anglo-Saxon and German-Japanese models represent the two main corporate governance archetypes; whereas the Italian one is considered as a mixed” one, a hybrid, i.e. it has some features in common with the above mentioned models while it also differs in some respects.. First of all, we study some ‘variables’ contained in codes of conduct which deal with what some boards of directors have defined as key success factors of corporate governance[37]. Basically, we focus on: board of directors’ functions, composition and dimension, CEO duality and non-duality, committee and corporate governancedisclosure. Secondly, we analyse these topics according to the main corporate governance international approaches, i.e. Agency, Stakeholder, Resource Dependence and Stewardship theories which are the basis of (with the exception of the latter) Anglo-Saxon, European and Italian models. Finally, we consider empirical research dealing with corporate governance topics mentioned above. The objective of the paper is two-fold, if we assume convergence international process impacts on corporate governance field. 1) We want to understand which international theory is adopted by codes. Thus, it is interesting to find out if convergence process towards a single standard of rules is ongoing or if each code which makes up the Anglo-Saxon, European and Italian models adopts different theories. 2) We want to verify if empirical research confirms principles efficacy contained in codes of corporate governance. The Research Questions are mainly two. RQ1) Is the convergence of codes of best practice relating to Agency theory or Shareholder approach an ongoing process? RQ2) Are the principles and rules regulated at international level (i.e. Anglo-Saxon, European and Italian) which underline codes of best practice, accepted or rejected by empirical research?As far as the methodological approach is concerned, the research objective and questions are pursued by a deductive approach. It consists of critical analysis of literature contributions, both international and national in the corporate governance field, a codes of best practice study, as well as analysis of empirical research carried out on Anglo-Saxon, German-Japanese and Italian samples.

4. Findings

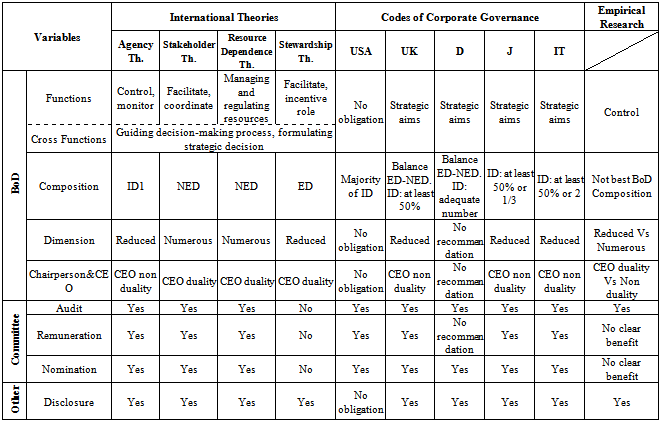

- The study of corporate governance international theories, codes of best practice[38] and empirical research has been conducted referring to: board of directors functions, board of directors composition, board of directors dimension,Chairperson and CEO roles, audit, nomination and remuneration committees, and finally corporate governance disclosure. These variables have been chosen as the study subject, because literature considers them as ‘possible factors determining’ good governance, i.e. critical success factors affecting company success, thus they ‘will have a predominant impact on the achievement of enterprise objectives’[39]. We should note that this issue focuses especially on Board of Directors, Committees and disclosure features, because they are ‘institution[s] that have arisen endogenously in response to agency problems inherent in governing any organization’. Each key success factor has been explained according to different theories existing in literature, and then explained by empirical research[40].First of all, we want to study how international corporate governance theories could explain codes of best practice variables, in order to understand which theory is adopted by the codes. Secondly, we will consider empirical research on Anglo-Saxon (i.e. outsider system), European (i.e. insider system) and Italian (i.e. Latin insider system) samples, in order to understand if International Theories, Codes of Corporate Governance and Empirical research are interlinked.Table 1 contains findings obtained by the comparison among international theories of corporate governance, American, English, German, Japanese and Italian codes of best practice and empirical research.Codes of best practice clarify that the two main functions of board of directors are, to identify and manage strategic aims directed at achieving, sticking to, and improvement of the so-called economic equilibrium. At present, the American code is the only one that does not mention anything related to this issue. According to different corporate governance theories, it is possible to distinguish the functions of Boards of Directors. Roles andresponsibilities change according to perspectives and theories adopted; yet, board of Directors relevance within the firm appears to be a shared principle[41]. In particular, as regards Agency theory, the board of directors should control, monitor and prevent manager power abuses from occurring to the detriment of shareholders; directors should be able to minimize agency costs, too[42]. According to Stakeholders theory, Boards should facilitate, coordinate and address all the people who have interests in a company. Thus, Directors should be able to help, foster and promote relationship with all stakeholders; the former manage and direct strategic choices directed towards shareholders and stakeholders expectations maximization[43]. Regarding ResourceDependence theory, board of directors have the role of managing and regulating resources or inputs that can be found in the environment. As well as forming relationships with other stakeholders the board of directors should seek out and combine resources obtained outwith the network creation, in order to increase innovative development, fundamental for the firm to be competitive[44]. Finally, Stewardship theory argues that boards should play an incentive role towards management and act as a facilitator in the relationship between manager and shareholders, with the aim of raising trustee and commitment relationship within the firm[45]. It is interesting to note that two cross functions exist which link the four theories above described, in particular strategic and performance optimization role[46]. The former consists of guiding the decision-making process, and of formulating strategic decisions by defining aims and policies that firm must pursue. As regards the latter, Tricker[47] suggests ‘the duty of boards is not only to protect wealth, but to create it’, so directors should maximize economic performance. Most empirical research shows that directors’ effectiveness (i.e. the ability to carry out their own duties and tasks) is coupled with board’s independence from management[40]. However, there is not a great deal of quantitative studies relating to board roles. Some state that directors over the 50/60-year age bracket notably perform a control function, because entry onto Board of Directors represents a moment of achievement recognition in career management, it is common for those who have served as CEO or other apical positions to remain on the Board as members[48]. Johnson, Daily and Ellstrand [49] argue that directors’ roles are classified as control, service and dependence resource, and ‘the relative volume of research devoted to the different board roles reflects the predominance of the control role’. In this case, codes do not assume one particular theory,

|

5. Conclusions

- International business scandals, firms bankruptcy, and financial frauds have fostered law updating process in the field of corporate governance; the need to create a system or a set of principles, duties and recommendations to apply to all companies operating in a given environment. The function of corporate governance codes is to outline organizational rules consistent with both corporate structure of each System-Country and, especially economic equilibrium goals to be worth over time. It is necessary to study and analyse codes, as they represent a fundamental corporate government tool in which company duties, rules and principles toward all stakeholders (e.g. minorities and majorities shareholders, employees, institutional investors, etc.) are identified. Code adoption, not only formal, could lead a company to become more transparent and accountable through a clear, visible disclosure on its governance model. It is essential that firms should assimilate those governance values, principles (e.g. responsability, accountability, transparency, etc.) required by financial market, as this could allow company to exploit some international competitive challenges or to obtain new financial capital (both equity and credit capital) especially in the current financial globalization context.From a comparative analysis of codes it emerges that a convergence process towards similar governance approaches at international level is underway. It should be noted, however, that each country – in spite of the convergence or standardization processes towards a single standard of rules – is affected by their social, historical, and economic background. As a matter of fact Shleifer and Vishny[92] and Levin[93] argue that ‘the legal and political environments are critical influences on the nature of corporate governance and thereby on corporate governance in every country’. For instance, German code recommends a Supervisory Board composed by employees, too; this is in support of stakeholder view rather than shareholder one. Italian code emphasises on the so-called ‘traditional model’ (existing only in Italy), leaving discretion to companies to adopt the Anglo-Saxon corporate structure (one-tier model) or German one (two-tiers model).Thus, from a comparative study among international theories (i.e. Agency, Stakeholder, Resource Dependence and Stewardship approaches) and corporate governance codes it would emerge that variables studied and contained in the codes would be better explained and regulated under Agency approach. For instance, the latter argues that it would be better to have a reduced board of directors, a greater number of independent directors, CEO non-duality, the committees institutions, and corporate governance disclosure. In addition, all codes of best practice regulate roles, functions and principles of Independent directors who are believed to be more effective monitors of company management[49], and they have arisen ‘in response to the agency problems inherent in governing anyorganization’[40].In fact, all codes analysed lead towards Agency approach. In a few other cases, codes adopt rules far from shareholder view (e.g. Germany, Italy and Japan), due to their own history, economic and social framework. Answering the first research questions (RQ1-Is the convergence of codes of best practice relating to Agency theory or Shareholder approach an ongoing process?), we can affirm that convergence process exists and is going to unroll. Globalization of relationships in stock financial market has led to a frequent review of national laws and regulations, according to paths consistent with culture, traditions and internal market conditions to each country, but at the same time they are projected to international best practices application. Clearly, according to contingency approach the lack of consensus may result from the chosen theoretical perspective.Empirical research on corporate governance iswidespread with the exception of studies concerning board of directors functions. It is interesting to note that literature intends to understand whether the solutions proposed by codes are indeed designed to maximize performance. Studies on corporate governance are very prolific and aim to demonstrate if standards are able to affect government efficiency and therefore economic equilibrium achievement. Answering the second Research Question (RQ2-Are the principles and rules regulated at international level (i.e. Anglo-Saxon, European and Italian) which underline codes of best practice, accepted or rejected by empirical research?), we could argue that empirical studies do not often explain critical success factors (e.g. dimension, composition of Board, CEO duality/non-duality, etc.) in the same way although both are the result of ‘corporate experience’ and best practices. It is probably due to the fact that corporate governance codes are expressed in general terms with few references to specific cases; therefore they are more easily applicable and adaptable to different firms operating in various contexts. Empirical research on the other hand study and analyse results from models applied to a sample of companies whose conclusions are then extended to all firms. Scholars use different dependent variables to measure performance, sometimes they use ROE, ROA, Tobin’s Q, market to book ratio. Thus, the lack of consensus on choice dependent variables could limit the generalization of corporate governance findings. Kakabadse and Kakabadse[94] maintain that ‘whilst the ambiguity of findings can be partly explained by the different research methodologies applied including sample size and the number of variables under investigation,’ other effects often ignored in quantitative studies such as a corporate culture, ethical norms of behavior and the levels of honesty expected in business, also determined this broad spectrum of conclusions.Empirical research does not always confirm principles efficacy contained in codes of corporate governance. However, we notice that most studies would seem to confirm what codes recommend, e.g. all codes suggest CEO non-duality would be better for several reasons above explained and at the same time most empirical research recommend that CEO and Chairman roles should be carried out by two different people.Finally, the board is a crucial element of corporate governance structure. It protects shareholders’ needs and also company, needs; it becomes a fundamental platform of monitoring of executives, success policy, of reviewing strategic aims, of ensuring integrity for shareholders and stakeholder interests, guarantee disclosure transparency. The market complexity, globalization, financial and economic environment turbulence make the role of board of directors more and more complicated. Thus, it could be a fascinating research field for Academic, Professionals, Business Practitioners and will remain the corporate governance core. The need for an osmotic process between literature and legislation emerges; if all studies carried out by Academics, Professionals, Legislator could converge and a continuous exchange of information and results could take place in order to develop shared principles and rules system everyone could benefit.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML