-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(5): 243-251

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130305.01

Braced for Turbulence: Understanding and Managing Resistance to Change in the Higher Education Sector

Nick Chandler

Management Department, Budapest Business School, Budapest, 1149, Hungary

Correspondence to: Nick Chandler, Management Department, Budapest Business School, Budapest, 1149, Hungary.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Through a review of the reasons and types of changes in higher education, this paper seeks to analyse the types of resistance to organisational change. Through extensive analysis of the findings of existing case studies, it is found that certain factors are commonly experienced by staff as key triggers for resistance to change, namely, the nature of faculty culture, a sense of territory, friction between functional divisions, resource allocation, traditions, leadership, communication, the power of unions and individual idiosyncrasies. It is found that Higher Education Institutions have a high propensity for resistance to change, especially in the context of mergers, whether the merger is forced or not. Role models and leadership are found to be critical success factors in change management and it is concluded that change can be achieved regardless of the peculiarities and complexities inherent in the culture of such institutions.

Keywords: Change, Resistance, Higher Education, Culture

Cite this paper: Nick Chandler, Braced for Turbulence: Understanding and Managing Resistance to Change in the Higher Education Sector, Management, Vol. 3 No. 5, 2013, pp. 243-251. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130305.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The realm of Higher education (HE) is no exception to change as traditional boundaries are rolled back and Universities and Colleges adapt to modern technology, changing demographics and academic interests. Barber etal. (2013) highlight the current needs for change so that the professional, vocational, continuing education and accrediting needs may be met and refer to the urgency of this need as an impending avalanche[1]. This paper will firstly consider the key reasons for change in HE in order to set a context for the analysis of the reasons and types of resistance to change in Higher Education. After this, the link between HE cultures and the potential level of resistance to change will be considered. This is followed by the reasons for resistance to change in HE and then the more common types of resistance are demonstrated with the use of a case study.

2. Reasons for Change in Higher Education

- The change drivers in both public and privateorganizations are often cited as: globalization, economic rationalism and information technology (DiSalvio, 2012; Burke and MacKenzie, 2002). These change drivers may also be considered in a higher education setting, but with additional pressures specific to the sector.The most commonly cited reasons for change found in the literature are: as a part of the Bologna process; to become more market-oriented; to change the type of institution; to offer new courses; to increase capacity; to become a research institution; required by Law (in the case of mergers in South Africa, Hungary, for example); changes in curriculum; voluntary / forced mergers; changes in management; a need to improve quality; financial problems e.g. decreases in government funding.According to Nair (2003)there are four key reasons for reform in higher education and perhaps the reasons listed previously could fit into one of the four categories[2]. Firstly, there is the technology-driven growth of information accessibility and greater communication. The information and communication revolution has hit every sector over the last decade and higher education is no exception to this. Secondly, globalization is another reason for reform. With the growth of the global communications revolution and greater accessibility to a global market, fierce competition is taking place in the world of intellectual capital. The brain drain, resulting in the loss of many intellectually-driven jobs from certain countries, is often seen as a direct by-product of the Internet era - as seen in the key aim of the European Research Area, as a part of the European Commission’s 2012 policy, of reducing the brain drain.Thirdly, underlying the trends of technologicaladvancement and an acceleration of globalization is competition between institutions. The idea of increased competition is something the higher education systems of many countries have almost never had to contend with before. In a global marketplace, education itself appears to be developing into a commodity and in a rapidly-changing world, the agility to define and redefine offerings to match current market needs is an important success factor. Competition in higher education comes from local and foreign universities / colleges, private institutions and the increasing number of “virtual universities”, with a seemingly endless range of courses and curricula in many cases set to suit the student. Barber et al. (2013) refer to MOOC (Massive Open Online Courses) as not only a lever for change in many institutions, but also that the adoption of MOOC by institutions may be a critical success factor. All these factors combined with the greater dependence on private sources of funds (rather than governments) lead to an increasing urgency to keep abreast of competition locally and, if possible, globally.Finally, accountability is another impetus for change and reform. Nowadays, there is a greater push for accountability from the public and from elected officials. Accountability refers to more than just a lack of adequate performance measures; it also refers to the lack of accountability of alienated local communities towards universities and colleges in terms of financial support. By being more accountable, local community colleges may obtain the uncommon edge over universities as they often receive greater local support through serving the immediate needs of the communities around them and thus maintain a sustainable level of government funds.

3. Change in Higher Education

- According to Balogun and Hailey (2004: 3,4), change is seen to occur in two forms: a punctuated equilibrium model and a continuous model of change[3]. Higher Education is certainly not prone to changing and adapting to its environment. It has often been accused of being a dinosaur out of touch with its environment or isolated in its ivory tower. The punctuated equilibrium model indicates that there are periods of adaptive and convergent change, broken by periods of revolutionary change. In education, revolutionary change may be required from time to time (e.g. the Bologna process) and as Balogun and Hailey (2004: 4) point out, revolutionary change is likely to be reactive and forced. Many reasons for change in HEIs can be seen as external (e.g. funding cuts, technology) and therefore the change is also reactive and forced. Change may also be in the form of convergent change where existing ways are adapted. Balogun and Hailey (2004) claim that with this type of change, there is likely to be significant resistance to change and a large degree of inertia. Changes in competitive conditions are less frequent in this model and it is possible to remain competitive without making any significant organizational changes. The continuous change model appears to indicate ongoing consistent change which may be hard to picture in HE institutions.According to Dehler and Walsh (1994), the more profound the changes, the greater the resistance to change will be[4]. However, there are levers that can facilitate the change, no matter how profound the change may be, and thereby reduce resistance (if managed suitably). Balogun and Hailey (2004: 43) refer to such levers as the cultural web of the organization, which involves: Technical subsystems (organizational structures, control systems); Political subsystems (formal and informal power structures); and Cultural subsystems (symbols, stories, routines and rituals).The following section will further consider some of the subsystems of the cultural web within the context of the link between cultural factors in HEIs and their potential impact on resistance to change.

4. Culture and Resistance to Change

- According to Becher (1987) the culture of HEIs may be seen as somewhat fragmented and it is only “by understanding the parts and their particularity, one can better understand the whole”[5]. This need for understanding culture in relation to change management is further emphasized by Kashner (1990: 20): "readying an institution to reply to the conditions that call for change or to innovate on the institution's own initiative requires a clear understanding of its corporate culture and how to modify that culture in a desired direction"[6]. According to Farmer (1990: 8),"failure to understand the way in which an organization's culture will interact with various contemplated change strategies thus may mean the failure of the strategies themselves"[7]. So what is the nature of HEI culture? Some writers, such as Giroux (2009) warn that the corporatization of higher education is a sliding slope which will result in the demise of HEIs and maybe even democracy itself[8]. Earlier writer such asClark (1987) claimed HEI cultures were extremely fragmented into what were referred to as ‘small worlds’[9]. Thus, although writers agree that due to the apparent link between culture and change, cultural factors require key consideration with a view to their impact on resistance to change within HEIs, it seems unclear whether HEI culture has a unitary or fragmented nature, if it fully indulged in the Disneyization or McDonaldization of higher education or what particular aspects could highlight the potential for resistance to change. The following section will seek to examine this issue further.

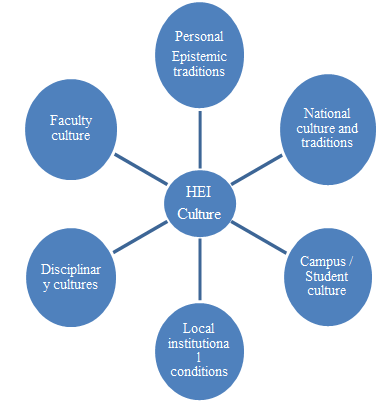

4.1. Culture in Higher Education

- In order to examine the complexities apparent in the culture of HEIs, the following framework has been used to provide a coherent structure for analysis, based on the work of Valimaa (2008), Becher (1987) and Hardesty (1995):Many HEIs are steeped in history, with unchanging traditions and members with long tenures, a strong culture is likely to prevail. According to Nahavandi and Malekzadeh (1993; 19), there are three elements to a strong / weak culture: the ‘thickness’ of the culture which refers to the number of shared beliefs, values and assumptions; the proportion of organizational members who share in the basic assumptions, which means the more shared assumptions, the stronger the culture) and finally; the clarity of the order of values and assumptions in terms of which are major and which are minor[10]. A larger number of clear shared assumptions is more likely in organizations where members have been there for a considerable period of time, such as long-standing university professors. Whilst a strong culture might provide a strong sense of identity and clear behaviors and expectations, it is also more prone to resisting change (Lane, 2007). This aspect is highlighted by Blin and Munro (2008) who found that whilst many institutions had adopted new technology and invested in virtual learning environments (VLEs), they found little change in actual teaching practices[11].

| Figure 1. The small worlds of culture in Higher Education |

5. Overview: Reasons for Resistance During the Change Process

- According to the extensive research of Pardodel Val & Martínez Fuentes (2003), the reasons for resistance depend on the stage of the change process being managed[20]. In the formulation stage, resistance is due to distorted perception, interpretation barriers and vague strategic priorities. The specific reasons for resistance are as follows: Myopia, or inability of the company to look into the future with clarity; Denial or refusal to accept any information that is not expected or desired; Perpetuation of ideas, meaning the tendency to go on with the present thoughts although the situation has changed; Implicit assumptions, which are not discussed due to its implicit character and therefore distort reality; Communication barriers, that lead to information distortion or misinterpretations; Organizational silence (limiting information flow with individuals who do not express their thoughts, so decisions are made without all the necessary information). Resistance is in the form of a low motivation for change and the sources are seen as: Direct costs of change; Cannibalization costs, that is to say, change that brings success to a product but at the same time brings losses to others, so it requires some sort of sacrifice; Past failures (leaving a pessimistic image for future changes); Different interests among employees and management, or lack of motivation of employees who value change results less than managers value them.Resistance is seen as due to the lack of a creative response. The specific reasons are: Fast and complex environmental changes (leading to no proper situation analysis); reactive mind-set, resignation, or tendency to believe that obstacles are inevitable; inadequate strategic vision / lack of clear commitment of top management to changes.In the implementation stage, there is a critical step between the decision to change and the regular usage in the organization (Klein and Sorra, 1996)[21]. The types of resistance have been cited in this case with the accompanying reasons for the specific resistance. Political and cultural resistance to change may be due to: implementation climate and relation between change values and organizational values, considering that a strong implementation climate when the values’ relation is negative will result in resistance and opposition to change; departmental politics or resistance from those departments that will suffer with the change implementation; incommensurable beliefs, or strong and definitive disagreement among groups about the nature of the problem and its consequent alternative solutions; deep rooted values and emotional loyalty; forgetfulness of the social dimension of changes.Internal resistance to change may be due to: leadership inaction, sometimes because leaders are afraid of uncertainty, sometimes for fear of changing the status quo; embedded routines; collective action problems, specially dealing with the difficulty to decide who is going to move first or how to deal with free-riders; lack of the necessary capabilities to implement change (capabilities gap); cynicism.

6. Reasons for Resistance to Change

- In Higher Education, as in any sector, it is difficult to generalize as to which specific types and reasons apply solely to higher education. Many of the reasons for resistance to change in the previous section could be foreseen in university and colleges (if not all). Due to the limitations of the length of this paper, only a few of the reasons for resistance to change in higher education will be dealt with in this section, although these are often cited as the most significant.

6.1. Faculty Members

- The Faculty culture and individual members have already been mentioned to some extent in this paper. Therefore it should come as no surprise that faculty members are well-known for their resistance to change. The situation can perhaps be best summed up using the quotations of a number of prominent writers on this topic:-“The scholar wants to be left alone in the conduct of the academic enterprise. He does not welcome innovation in instructional procedures, in instructional arrangements, or in the organization and operation of a college or university. . . The scholar is a conservative in his attitude towards and appreciation of the academic process.” Millett (1962; 104)“We cannot help but be struck by the virtual right so many academics seem to possess to go their own way, simply assuming they can do largely as they please a good share of the time, all in the nature of rational behaviour.” Clark (1987; 148).“Resistance to new ideas is inborn among academic communities.” Becher (1989; 71)Thomson (1993) undertook extensive research at Earlham College in looking for an answer to the question: Why do certain faulty members resist bibliographic instruction? Although this is only one area of resistance to change it is worth considering the findings of this research as they provide considerable insight into the reasons for resistance to change in higher education[22]: 1. “They are overworked. . . . They really do not have time to learn new things, especially when the proponents of ‘new things’ sound a bit like they are selling aluminium siding.”(p. 103).2. “They are obsessed with coverage and they have packed their courses with assignments. There is no room for additions or changes” (p. 103). 3. “[They] do not want the sanctity of their classrooms violated. It is not paranoia that drives them to this attitude. There are all sorts of real people, from presidents to trustees to students to vigilante groups on the left and right, who cheerfully tell teachers what should be going on in their classrooms” (p. 103). 4. “Most college teachers are prima donnas. On most campuses, despite their real sufferings and sacrifices, faculty members enjoy an extraordinarily privileged status. They regard librarians as they regard secretaries and ground keepers, as their errand boys and girls, not as their colleagues” (p. 103). 5. “College professors are often not very self-critical. They may be good lecturers and writers, but they are not in the habit of subjecting their own behaviour to criticism. . . . We do not like our ignorance to be visible” (p. 103). The issues involving faculty members have been listed first of the many factors that cause resistance to change as these seem to be the most often cited or potential reasons for change amongst the current literature. Faculty members – for all number of reasons – appear to be extremely prone to resist change.

6.2. The Time Factor

- One particular factor is mentioned across the board as the heaviest burden for staff, not only in Higher Education but in education at all levels: time pressures. According to Hardesty (1995) faculty are often pressured by time and as such they are likely to resist any change proposals that take up more of their time[23]. Likewise, the teaching syllabus for many Faculty members is built up over many years of practice and members have spent a lot of time developing strategies that they consider to be effective and suit their personal style. This being the case, changes in a curriculum will be resisted on the basis of the amount of time and effort that has been spend putting the syllabus together and in some case, could be considered an individual’s life work.

6.3. A Sense of Territory

- HE culture is highly fragmented with a wide variety of sub (and counter) cultures. These subcultures also create feeling of ownership concerning symbolic territories (spheres of ownership) and there present a significant potential for resistance to change, especially when a proposed change may threaten these perceived territories (Kashner, 1990).

6.4. Administrators vs. Faculty

- Historically the greatest clash during change in HE has occurred between the administrators and the faculty (Kashner, 1990). This is due to another aspect of HE culture: traditions. Faculty are often perceived as the ‘gatekeepers’ of culture and traditions on campus. Thus, when long held cultural beliefs are challenged by a proposed change, it is natural for faculty to perceive that change as threatening. Therefore, unless the cultural elements are addressed, there will be significant resistance from faculty to any change effort.

6.5. Resource Allocation

- According to Diamond (2006) another reason for resistance to change in Higher Education is that of resource allocation. As mentioned earlier, individuals are committed to certain disciplinary or departmental cultures and, therefore, if any resources are shifted away from these areas and reallocated, then it is viewed as a loss to be avoided at all costs (Diamond, 2006: 2)[24]. This is a significant potential for resistance to change as funds of universities and colleges are often limited and cost-effectiveness and budget allocation are just two of a number of reasons for reallocation of resources.

6.6. Traditions: Maintaining the Status Quo

- Traditions have already been discussed in detail in this paper, and strongly upheld traditions appear to indicate the potential for resistance to change and an inclination for maintaining the status quo. According to Diamond (2006) alumni are a major force for maintaining the status quo even if the beliefs about an HEI are merely wishful thinking or based on conditions that no longer exist.

6.7. Leadership

- Many leaders in universities and colleges are unprepared to lead change and as such staff may develop a lack of trust in management, an unclear vision, ambiguous aims and objectives and leave the staff feeling isolated and alienated (to name but a few). In fact academic management may lack the training simply because they come from an academic rather than a management or business background. A lack of skills or knowledge about change models may lead to severe resistance to change. According to Diamond (2006), most leadership and faculty position are filled with a view to selecting candidates likely to preserve the status quo rather than being an agent of change. Within the scope of the leadership issue, it is worth also considering faculty governance. Faculty culture supports faculty governance by consensus. According to Hardesty (1995), if governance by consensus is combined with the value that faculty culture tends to put on scepticism and cynical analysis, then the resulting culture inevitably will resist change.

6.8. Communication

- Poor communication systems are often cited as a main cause of conflict and resistance to change in many organisations, not only in Higher Education. This however does not only refer to communication between departments or between faculty staff and administration but also between the institution staff and political leaders who make decisions which have an impact on the HEI, the community the HEIs serve, schools that prepare students for higher education and employers that will employ the newly graduated students. Such poor communication can cause a lack of vision or direction, insecurity of staff, lack of trust in the change process, to name but a few.

6.9. Power of Unions

- The power of Faculty unions varies from one institution to another and from one country to another. Diamond (2006: 3) cites these unions also as factors causing resistance to change as ‘on a number of campuses faculty and administrators have found that the wording of their faculty contract actually limits their ability to explore new and innovative instructional design and formats’. In other words, the Unions have put into staff contracts some resistance to change.

6.10. Individual Resistance

- According to Schoor (2003), the most common reasons for individuals resisting change in higher education are as follows: Self-interest (the change is harmful); Psychological impact (job security, social status etc); Tyranny of custom (caught up in the web of tradition); Redistributive factor (changes in work roles, responsibilities, tasks);Destabilisation effect (new staff / management); Culture incompatibility (clash between (sub-cultures) and; Political effect (power relationships)[25].According to Huczynski and Buchanan (1991; 533), a similar list could be compiled as follows: Selective perception; Habit; Inconvenience or loss of freedom; Economic implications; Security in the past; Fear of the unknown; Parochial self interest (protecting the status quo); Misunderstanding; Lack of trust; Contradictory assessments and; Low tolerance of change[26].

7. Types of Resistance to Change

- According to practical experience, there are two main types of resistance to change: Active and Passive. When referring to active resistance to change, the sort of behavior includes: Arguing, ridiculing, blaming, distorting, tracking, sabotaging, threatening, intimidating, blocking and rationalizing (Ingbretsen, 2008)[27]. Passive resistance to change entails such behavior as ignoring, non-participation, procrastinating, not implementing, mishandling, withholding, pretending, avoiding. According to Coetsee (1993) the types of resistance for a teacher are passive or active, although active is also referred to as aggressive[28]. Coetsee (1993) indicates that passive resistance is not aggressive behavior in the same way active is and that active resistance varies in intent. For example, blocking behavior refers to actions stopping or ending the change whereas sabotage is aimed at not only stopping the change but also disrupting and perhaps even destroying the social systems where the change takes place.However, in higher education is more complex thansimply categorizing reactions into passive or active. According to Theron and Westhuizen (1996) from literature and research through interviews it was found that there is resistance if there is change but also that there is resistance if there is no change. In other words, in higher education, it would seem that there is a natural tendency to resist, whether the change takes place or not[29]. Therefore, to analyze this further, it is worth considering a case study of transformation in Higher Education as an example of some of the types of resistance that can occur. This is not intended to generalize for all cases of change in higher education but it provide some insight into this area.

8. A Case Study of Resistance to Change

- As previously mentioned, the types of resistance to change may vary from one HEI to another. The case to be analyzed involves a merger of a University and a College in New Zealand. A merger is a profound change for both organisations but perhaps more so for the college in this case as there is a need to change location, leadership and become assimilated into the university’s culture, resulting in a loss of identity and, potentially role models in the leadership of the college. In this merger, the University of Canterbury (UoC) is the dominant culture and Christchurch College (CCE) is the acquired institution. They have a history of cooperation in a range of academic programmes and both have a far-reaching historical background in New Zealand[30]. The reasons for this merger are: to keep with the national trend of higher education mergers; for the College to be moreresearch-focused; to align with practices overseas; and to make up for cuts in government spending as the prospects of independence were untenable[31]. With these reasons in mind, the merger was seen by both parties as inevitable. It will be interesting to see if this fatalistic approach has an impact on the cultural processes in the merger in terms of a willingness or reluctance to assimilate.At the conflict stage of acculturation, management anticipated a high potential for conflict and resistance to change and therefore used a number of tools in an attempt to reduce resistance to change: Working parties (with mixed UoC and CCE staff); a merger website (where staff could ask questions); staff forums (where management presented information and invited questions); Management committee meetings. where management received updated merger information and asked questions; Staff department meetings; The CEE climate survey (this was undertaken in 2005 as a means for staff to appreciate the impact of the merger and to understand, through the survey, staff’s perceptions and issues) and; CCE Staff Consultation Policy (to support consultation, to show listening to others, consider responses and decide how to act) (Brown, 2008)[32]. Brown (2008) undertook further research into this case by interviewing staff and the reasons and types of resistance to change were found. The types of resistance to change referred to in the case study are confirmed by Schoor (2003), when referring to the typical types of resistance to change in higher education. Shoor (2003) puts them into two categories. The first is conscious acts, such as retaining the status quo and filtering or withholding information. The second type is unconscious acts, such as projection and background conversations. All of these occurred in the case studies. The following is a sample of some of the comments made: “Management did not act on feedback, leading to a lack of faith in consultation and staff feeling excluded and feeling powerless”From the comment it seems that this lack of response lead to other problems which could seriously damage the merger process, such as a loss of trust in the consultation process. There is also the issue here that staff feels powerless. Although this is referring solely to the consultation process in the merger, it is worth mentioning that according to Mullins (1999) all staff needs to have some power or at least know the limits, who will grant power and how power can be assigned or earned, without this resistance to change is more than likely. This losing of trust and feeling of powerlessness show a lack of basic managerial philosophies and resulted in exit behavior as staff were disillusioned with the merger process and their place in the merged company, and felt far too many jobs had been lost, their future looked uncertain and they felt undervalued. The exit behavior as resistance to change took the form of disengagement, withholding effort, escapism and defiance.“Management are only concerned with accomplishing the merger and not the staff”This is another example where management seems to have failed to maintain a relationship with staff. Again staff feels alienated and as such they are likely to resist change. The type of resistance to change in this case was staff leaving the organization. “Merger was seen to entail ‘disestablishment’ for the acquired institution”According to Brown (2008; 81), staff said that the merger had a negative impact on their relationships, confidence, moods, and career. It also provoked self-assessment, which lead to trauma and stress. In fact this kind of stress is referred to by Berry (1980) as acculturative stress, referring ’to the psychological, somatic and social difficulties associated with the acculturation process’. This stress leads to defiance in the face of leadership and in more extreme cases, staff quitting their jobs[33].“The College Principal became the UoC Vice Chancellor and was seen as a puppet for UoC”The College Principle was the figurehead of the college and initially seen as the figurehead of the merger from the College staff point of view(Brown, 2008; 103). By changing position, he was no longer the role model. Staff also complained of a lack of presence of the UoC Vice Chancellor at change proposal meetings in the early stages of acculturation. Staff lost trust and respect and this resulted in resistance in the form of defiance as seen in the staff comment: ‘I wouldn’t follow that leader anywhere, let alone into the public loos…’ (Brown, 2008; 78).“Seeking solace in other colleagues”This seems to be a similar effect as that shown in the famous film, the Dirty Dozen: an Army Major has to get his uncooperative group to start acting like a unit and to achieve this they're forced to become allied against a common enemy – the American General Staff, in other words they unite solely because of shared dislike of the authorities. Similarly in this case, groups form and work together as a team only because they have a shared ‘enemy’ in the management and shared difficult circumstances. In this case, the staff felt management had no concern for staff and would not listen so they looked to one another for support. The fact that UoE and UC staff bonded and interacted may be seen as a good thing, were it not for the fact that it was as a comfort from the stress and trauma being caused by the merger process. Although this actof solace is not a form of resistance to change, it can be seen as a form of separation, although in this case not the separation of the cultures of the acquired and acquiring company but the separation of the staff from the management. It also indicates an unwillingness of staff to assimilate to the vision of a new culture held by management.“Changes in workload”According to Mullins (1999; 474), when a merger takes place, it can lead to role incompatibility where for example teachers are required to fulfill tasks that they feel unprepared or unqualified for[34], role ambiguity where staff doesn’t have a clearly defined role in the new merged organization and role overload (or underload), with the former occurring if jobs are lost and others are expected to take on more work and the latter when, for example, managers are redundant in their role as a result of the merger. From the merger it seems that by restructuring, many departments were merged leading to different goals and internal environments within departments. This in turn led to resistance in the form of refusal to undertake tasks and conflict between staff in cases of role ambiguity.Language: The merger should have been described as a takeover from the start or an ‘absorption’ of UCC (Brown, 2008; 104).Language enables us to perceive things such as ideas and emotions, develop trust and influence others. According to Mullins (1999), perceptions are part of a person’s reality and value judgments can be a source of potential conflict. In this case people perceived through the management that the merger would not be a big change and business would pretty much carry on as usual or at least on equal terms. Language was seen as not only a cause of faulty perceptions but also as an expression of resistance to change, whether as an expression of resentment or defiance of leadership but also to express frustration and anger at the change process and the way it was being handled.

9. Conclusions

- Higher Education is an unusual case when considering resistance to change. There is a far greater likelihood of resistance due to numerous aspects which are particular to the culture of Higher Education Institutions. Furthermore, some research indicates that HEIs and the Faculties / Departments therein are prone to resistance of some form or another, whether there is enforced change or not. Although it is hard to imagine a strategy for getting through the numerous problems that were created as a result of the merger in the case, it could be seen that the only option is to introduce ‘new blood’ to the organization. Often in the case of deculturation, a complete change of management of the acquired firm is recommended as no intention to adapt has been shown. In this case, perhaps not only the management of the acquired firm but members of the acquiring firm should be considered for replacement. Either way, role models and strong leadership are certainly required to regain the trust, commitment and dedication of staff in the HEI undergoing significant transformation due to a merger. Finally, although it looks like HEIs facing change are facing an almost impossible task, methods have been discovered to manage resistance to change. According to the findings of Theron and Westhuizen (1996), the following could be considered as a means of reducing resistance to change in Higher Education: -ο Education and Communication. This refers to educating and informing the teachers involved in the change as early as possible about the necessity for and the logic of the change. Such a strategy would take the form of individual / group discussions, memoranda and reports.ο Participation and Involvement. By involving teachers in the change as soon as possible, they are more likely to accept responsibility for it. There is less change of resistance to change when teachers have shared in decision-making and responsibility. ο Facilitation and Support. The leader of the HE institution, as an agent of change, can use a number of techniques to reduce resistance such as: re-educational and emotional support programmes and providing the opportunity for those teachers involved to talk while the leader listens attentively.ο Negotiation and Agreement. In this case, the leader offers something of value in exchange for a diminished resistance to change. This ties in with the issue of the power of unions which was mentioned earlier in this paper as a factor for resistance.When considering the best strategic option for a higher education institution, the leader will need to bear in mind a number of variables as specified by Kotter and Rathgeber (2006) as: the amount and type of resistance expected; the position of the leader compared to that of the teachers offering resistance (in terms of authority and trust); the locus of relevant data for planning the change; the energy required to implement it; and what is at stake (e.g. the impact of the resistance on the success of the organization or the outcome if change does not occur)[35].In the past, Educational institutions are often referred to as dinosaurs (behind the times) and academic staff as the men in their ivory towers (out of touch with reality); it seems that there is a grain of truth to this due to the institutions particular culture and history. Resistance to change is certainly an important factor in contributing to this reputation. However, with a strategic and analytical approach to managing change even great transformations such as mergers between two large universities have been successful (e.g. London Metropolitan University) and become models for change for other institutions to follow.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML