-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(4): 218-222

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130304.04

The Moderating Effects of Age and Tenure on the Relationship between Organizational Identification and Job Satisfaction

Zeynep Oktug

Department of Psychology, Istanbul Kultur University, Istanbul, 34156, Turkey

Correspondence to: Zeynep Oktug, Department of Psychology, Istanbul Kultur University, Istanbul, 34156, Turkey.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purpose of this study was to examinethe moderating effects of age and tenure on the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction. Data were obtained using a survey method from a sample of 180 sales assistants in Istanbul. Two different types of tenure were examined, namely organizational tenure and job tenure. Regression analyses were conducted in order to test the moderating effects of age, organizational tenure and job tenure. The results of the study showed that, while age and organizational tenure do not moderate the relationship, job tenure moderates the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction of employees. Limitations and suggestions for future studies are discussed.

Keywords: Organizational Identification, Job Satisfaction, Age, Organizational Tenure, Job Tenure

Cite this paper: Zeynep Oktug, The Moderating Effects of Age and Tenure on the Relationship between Organizational Identification and Job Satisfaction, Management, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 218-222. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130304.04.

1. Introduction

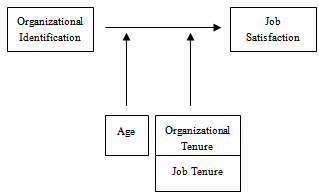

- Since 1990s, researchers give attention to organizational identification, which can be defined as a process in which employees interpret first the identity that membership in particular organization offers and then the degree to which this identity resonates with them[34]. Organizational identification affects employee’s job attitudes and behaviors[20] and it has positive effects on different work outcomes such as lowered turnover[1], increased extra-role behavior[33] and job satisfaction[38]. Organizational identification drives from social identity theory[31] which refers to an enduring state that reflects individuals’ readiness to define him/her-self as a member of a social group[15]. Social identities play an important role for the attitudes and behaviors of employees because being a member of an organization helps to answer the question of “Who am I?”[3]. Organizational identification is a specific form of social identification[23]. According to Pratt[28] employees have two main and basic motives for identification with an organization. The first one is the need for self-categorization, which indicates seeking a unique place and feeling different from the other members of the society; the second one is self-enhancement, which indicates feeling pride through association with an organization.Job satisfaction, which is defined by Locke[21] as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences”, has always been of interest to the researchers working in the field of organizational psychology. It involves the attitudes of employees towards various aspects of the job[17]. Research shows that there are a number of antecedents of job satisfaction such as role perceptions, job characteristics and supervisory behaviors[10]. Supportive aspects of the work environment have positive influences on job satisfaction[7]. Employees intend to quit or mentally withdraw from the organization when they are dissatisfied with the job[22]. A large body of research indicates that organizational identification is associated with greater job satisfaction[19]. Employees who identify with the organization consume more energy, exert more effort, make more time for the work, and stay longer with the organization[37].In organizational identification process, in order to determine their organization’s identity, employees decide what they believe are their organization's central characteristics[2]. Then they determine the degree to which they define themselves by the same characteristics[4]. If these matching characteristics provide employees an enhanced status that positively reinforces their self-concepts, they will identify strongly with membership in the organization[13] which in turn elicits greater job satisfaction. Employees, who identifies with the organization, pay attention to what they have in common with other members[9].Riketta[30] found in his meta-analysis that age and tenure significantly related to organizational identification. As tenure increases, employees adapt to organizational values[16]. Cakinberk at al.[11] revealed in their study, which comprises 135 teachers and school managers, that organizational identity is higher by employees who are over 30 than the employees under 30. Natarajan & Nagar[25] found that tenure had a positive effect on job satisfaction. While job tenure comprises the total time an employee performs the job, organizational tenure comprises the time an employee works in a particular organization. Bos et al.[8] revealed in their study that job satisfaction increases with age. The differences in job satisfaction related to age are greater than the differences associated with other factors like gender, education or income[35]. With increasing age, the rewards also increases and that can be a reason for the positive relation between age and job satisfaction[24]. Another possibility is that the older people move into other jobs which may be more satisfying[18]. Clark et al.[12] revealed in their study that job satisfaction declined on average until the age of 31 and rises thereafter. Although many research examined the relation between employee age and job satisfaction, the answer of the question whether this relationship is linear or curvilinear, remains unclear[27].The aim of this study is to examine the differences between organizational identification and job satisfaction in terms of age and the moderating effects of age and tenure on the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction. Figure 1 provides the hypothesized model for the study.

| Figure 1. Hypothesized model for the study |

2. Method

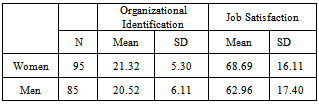

- The participants were 180 sales assistants (95 women, 85 men) working in ready-made clothing sector in Istanbul. In terms of age, 43.9 % of the subjects were 18-24 years, 35.6% 25-29 years, 16.7 % 30–39 years, 3.9 % 40-49 years. In terms of organizational tenure, 46.7 % of the subjects had worked at their respective organizations less than 1 year, 43.3 % 1–3 years, 7.8 % 4–6 years, 0.6 % 7–9 years, and 1.7 % 10 years and over. In terms of job tenure, 15 % of the subjects had worked less than 1 year, 37.8 % 1–3 years, 23.3 % 4–6 years, 13.3 % 7–9 years, and 10.6 % 10 years and over.Two senior psychology students with high academic grades for the Organizational Behavior course were appointed to help in conducting the survey. For this purpose, they visited 20 shopping malls randomly selected among the 50 shopping malls in the European side of Istanbul. 250 sales assistants approached, 180 completed the questionnaire on a convenience basis; the return rate was thus 72 %. For measuring organizational identification, Organizational Identification Scale developed by Mael and Ashforth[23] was used. And the Cronbach’s alpha for the 6 item scale was 0.87. Tuzun[32] in her study in Turkey, revealed that the scale had a single factor structure and it explained 48.13 % of total variance. The internal consistency coefficient was 0.78. For this study the Cronbach’s alpha was 86.6 %.For measuring job satisfaction, Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) was used, which was developed by Weiss et al.[36]. Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was 0.94. MSQ was translated into Turkish by Baycan[6] and Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.77. For this study the Cronbach’s alpha was 94.6 %.

3. Results

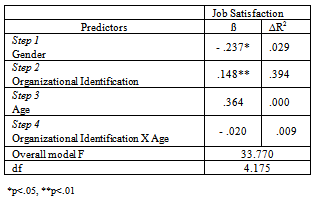

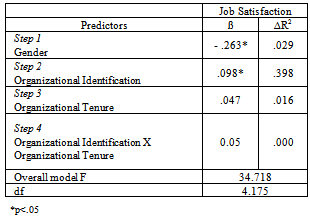

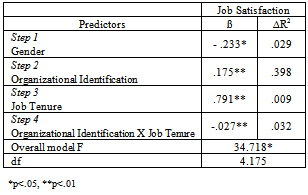

- According to the correlation analysis results, there is a positive relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction (r= 0.64, p< 0.01). Table 1 provides means and standard deviations of organizational identification and job satisfaction.

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The results of the present study showed that age and organizational tenure do not moderate the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction. However, job tenure has a moderating effect on this relationship. With other words, while the time employees have worked in a particular organization doesn’t have a moderating effect on the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction, but the total time employees have performed their jobs moderates this relationship.Organizations try to improve their effectiveness continuously. Job satisfaction which is positively related to job performance[29] is a fundamental factor for an efficient organizational life. Organizational identification on the other hand, leads to increased support of the organization[23] and decreased employee turnover[26] has positive effects on employees’ effort, cooperation and citizenship behaviors[13, 5], which contributes to the job satisfaction. According to the findings of this study age does not seem as a moderator between organizational identification and job satisfaction. It is considered there could be some variables other than age, which affect this relationship. In future studies other variables can be tested in terms of their effects on the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction. In their study, Ferris et al.[14] measured three different types of tenure (organizational tenure, job tenure, tenure working for current supervisor) and found that organizational tenure and job tenure (also tenure working for current supervisor) positively affects job satisfaction of employees. In present study, in terms of their moderating effect on the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction, different results for these two types of tenure were revealed. The period that an employee works in a particular organization, doesn’t have the same effect as the period he practices his professions. The total time for practicing a particular job seems to be more effective on the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction. Natarajan and Nagar[25] stated in their study that with tenure the employee resolves the dilemmas and becomes more adjusted with the organization which in turn elicits job satisfaction. In terms of the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction, this study showed that becoming more adjusted with the organization is less effective than gaining experience from a particular job over time. There are some limitations of this study. The educational background of the employees can have some effects on their job satisfaction or organizational identification. In future studies, the effects of educational background can also be examined. The sample of the study comprises only the sales assistants. The employees working in different sectors can have different motives, so that they can produce different results. In future, similar research can be conducted with employees who are working in different areas.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML