-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(3): 135-141

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130303.01

Quality of Working Life and the Police

Simon Easton, Darren Van Laar, Rachel Marlow-Vardy

Department of Psychology, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, PO12DY, UK

Correspondence to: Simon Easton, Department of Psychology, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, PO12DY, UK.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This article reviews the development of the concept of quality of working life (QoWL) and its application to the police service setting. The assessment of QoWL and is discussed and a new measure of QoWL are presented. The WRQoL survey[1] comprises of 23 items measured on a five point Likert scale (1-Strongly Disagree, 5-Strongly Agree). The reliability of the WRQoL scale as measured by Cronbach’s Alpha has been shown to be 0.94. The opportunity to obtain valid assessment of QoWL in the police service provides a basis for informed and targeted interventions which can be associated with enhancement of quality of working life of staff, improved performance and reduction of costs. The Work-Related Quality of Life scale is an established assessment measure which shows promise as a valid measure for use in the promotion of quality of working life among police service staff. Published evaluations of the Work-Related Quality of Life scale[1] indicate that this measure provides a reliable and valid assessment of the key factors affecting the work experience of respondents, and may serve as a basis for surveys of staff in the police service setting.

Keywords: Quality of Working Life, Stress, Police Work, Work-Related Quality Of Life Scale, Staff Surveys

Cite this paper: Simon Easton, Darren Van Laar, Rachel Marlow-Vardy, Quality of Working Life and the Police, Management, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 135-141. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130303.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Police service officers and staff can be asked to undertake tasks which most other people would find exceptional. Police officers may be asked to work in settings and conditions, or at a level of personal discomfort or risk which are relatively unusual. Whilst many of these additional or exceptional demands are expected, there are stresses and strains which are not anticipated by those committing to police work, and there are repercussions for life outside work which can lead to substantial costs both personally and socially. Whilst stress in the police setting has been much studied, and is seen as an issue to be addressed and managed, endeavours to prevent or counter undue levels of strain and associated consequences often seem less effective than promised[2]. Attempts to understand and tackle stress and strain in the police context might be compromised from the start if the broader work context is not taken into account. The concept of quality of working life has been developed to provide a way of understanding the interactions between core facets of the working environment so that cause and effect can be distinguished, and interventions appropriately targeted. This article will briefly discuss the attempts to address stress in the police setting before reviewing the development and expansion of the conceptualisation of stress within the broader notion of quality of working life (QoWL). Definitions and attempts to measure QoWL will then be reviewed, and some observations are made as to the current status of the concept of QoWL and its potential application in the Police setting. Preliminary indicative results of a survey of QoWL are presented in the context of benchmark data based on surveys of UK staff on higher education.

2. Stress, Job Satisfaction and the Police

- Stress has been recognised as a substantial issue for employees and employers. Smith et al.,[3], reporting to the Health and Safety Executive in the UK (HSE), showed that about 20% of the workers reported very high or extremely high levels of stress at work. More specifically, the Health and Occupation Reporting network datasets, as reported by the HSE in 2008, reported high incidence rates of work-related mental illness for various staff groups in public sector security based occupations such as police officers, prison officers, and UK armed forces personnel. This recognition of Police work as a well-known high-stress occupation is not new (e.g.:[4],[5]). There are elements of police work which are quite unique, and research over the years has identified a long list of stressors associated with police work (e.g.[6 – 8]).Whilst Police officers have traditionally been expected to be hardy and resilient, and so able to cope with the demands of their work, the links of stress to police officers' illness and absenteeism have been highlighted[9]. The causes of stress among Police officers are not always as those outside the police might expect. For example, Hart et al.,[10] challenged the stereotype of policing that suggests operational experiences are the cause of stress and distress by showing that perceived quality of life can be substantially determined by police officers' personalities.Attempts to develop a better understanding of the causes and effects of stress in policing have included other factors such as the role conflicts between job and home. Hageman[11] examined police officers’ perceptions of these role conflicts, and concluded that police officers as a group did not generally perceive their job problems as causing marital problems. Reduced job performance, personnel turnover, and low morale were, however, linked to job and marital stress. Smith et al.,[3], concluded that marital status influenced the reporting of stress, with those who were widowed/divorced or separated being more prevalent in the high reported stress category.Researchers have identified a range of contributors to the stress and distress experienced by police officers. Territo & Vetter[12] endeavoured to summarise the research by suggested that most of the stressors affecting Police Officers can be grouped into four categories: (1) organisational practices and characteristics, (2) criminal justice system practices and characteristics, (3) public practices and characteristics, and (4) police work itself. Understanding stress however appears to require attention to other factors. Job satisfaction, for example has been studied in detail, and its relationship to stress and distress appears to be complex. Hart[13] showed that life satisfaction was determined, in order of importance, by non-work satisfaction, neuroticism, non-work hassles, job satisfaction, non-work uplifts, extraversion, work hassles, as well as other less salient factors.More specifically, there is evidence that Job satisfaction is primarily associated with positive affect, life satisfaction, and self-esteem, while job stress was primarily associated with negative affect and alcohol consumption [14]. The relationship of stress to job-satisfaction thus appears complex, and, whilst the factors affecting one aspect might at times affect the other, these two aspects of someone’s work experience seem likely to vary independently to a substantial degree. Thus, it has been suggested that four traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability (low neuroticism) - are among the best dispositional predictors of job satisfaction and job performance[15].Stress and job-satisfaction will be often be inextricably linked in terms of effect in the working environment, as illustrated in research which indicates that the experience of harassment and the quantity of leave taken were associated with turnover intentions[16]. Brough and Frame found in this research that supervisor support could be a strong predictor of job satisfaction, and their work suggested that intrinsic job satisfaction can be an especially strong direct predictor of turnover intentions[16]. Their results also support the distinction between the two types of job satisfaction, intrinsic vs extrinsic in the context of turnover research[16]. This complex inter-relationship between these two aspects of work means that the consideration of one aspect in isolation may be limiting. Thus, management of stress will tend to be affected by job satisfaction, and vice versa. For example, research with police officers has linked high levels of job satisfaction with lower levels of stress and improved psychological well-being[17].

3. Quality of Working Life: the Broader Context for Stress and Job Satisfaction

- While the academic literature often refers to the greater context, much research tends to focus on just one aspect of the work experience in isolation. The complexity of an individual’s experience in the workplace often appear to be set aside in an endeavour to simplify the process of trying to measuring “stress” or some similarly apparently discrete entity. It may be, however, that the consideration of the bigger, more sophisticated picture is essential, if targeted, effective action is to be taken to address quality of working life or any of its sub-components in such a way as to produce real benefits, be they for the individual or the organisation. The broadest context in which an evaluation might be made might be identified as Quality Of Life. Quality of working life has however been differentiated from the broader concept of Quality of Life[18]. To some degree, this may be overly simplistic, as quality of work performance has been seen as affected by Quality of Life as well as Quality of Working Life[19]. However, it will be argued here that specific attention to work-related aspects of quality of life is valid and useful. Whilst quality of life has been more widely studied, the concept of quality of working life remains relatively unexplored and unexplained. A review of the literature reveals relatively little on quality of working life. Where quality of working life has been explored, writers differ in their views on its core constituents, as will be discussed below. It can be argued that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts as regards Quality of Working Life, and, therefore, the failure to attend to the bigger picture may lead to the failure of interventions which tackle only one aspect. A clearer understanding of the inter-relationship of the various facets of quality of working life offers the opportunity for improved analysis of cause and effect in the workplace. This recognition of Quality of Working Life as the greater context for various factors in the workplace, such as job satisfaction and stress, may offer an opportunity for more cost-effective interventions. The effective targeting of stress reduction, for example, may otherwise prove difficult for employers pressured to take action to meet governmental requirements.

4. Quality of Working Life: A Brief Review of the Literature and Identification of Key Components

- One of the earliest uses of the term “Quality of Work Life” appears in the work of Mayo in studies on the way environment affected workers’ performance[20]. Goode[21] has suggested that the term “Quality of Work Life” was first used by Irving Bluestone in the 1960s when involved in designing programmes to increase worker productivity. Much research interest in the concept led to a conference in 1972, and then formation of “The International Council for the Quality of Working Life” in an endeavour to draw together the disparate strings of research onto related aspects. No single definition of terms emerged, and, initially, there was often little to distinguish between the concepts of Quality of Working Life and Job Satisfaction. Kandasamy and Ancheri[22] have suggested that the term Quality of work life has since been viewed in a variety of ways, including as a movement and as a set of organisational interventions.Definitions of Quality of Working Life (QoWL) vary according to the theoretical stance of researchers. As a result, various models of QoWL have been proposed, each drawing upon different combinations of a wide range of factors, which in turn are mostly drawn from theory, and only rarely from the findings of empirical research. For example, dimensions of QoWL have been proposed as: adequate and fair compensation, safe and healthy working conditions, opportunities for personal growth and development, satisfaction of social needs at work, protection of employee rights, compatibility between work and non work responsibilities, and the social relevance of work life[23]. Taylor[24] proposed more pragmatically that the essential components of QoWL could be identified as the basic extrinsic job factors of wages, hours and working conditions, and the intrinsic job notions of the nature of the work itself. He suggested that a number of other aspects could also be added, including: individual power, employee participation in the management, fairness and equity, social support, use of one’s present skills, self development, a meaningful future at work, social relevance of the work or product, effect on extra work activities. Taylor’s pragmatism led to the suggestion that relevant QoWL concepts might vary according to organisation and employee group. Warr et al.[25] in an investigation of QoWL, identified a different list of apparently relevant factors, including work involvement, intrinsic job motivation, higher order need strength, perceived intrinsic job characteristics, job satisfaction, life satisfaction, happiness, and self-rated anxiety. They discuss a range of correlations derived from their research, which contributed towards development of models of QoWL, such as those between work involvement and job satisfaction, intrinsic job motivation and job satisfaction, and perceived intrinsic job characteristics and job satisfaction. In particular, Warr et al. found evidence for a moderate association between total job satisfaction and total life satisfaction and happiness, with a less strong, but significant association with self-rated anxiety. Thus, whilst some authors have emphasised the workplace aspects in QoWL, others have identified the relevance of personality factors, psychological well being, and the broader concepts of happiness and life satisfaction.The difficulties in defining the concept of QoWL continued to be illustrated in the literature, however, as authors proposed new models highlighting the relevance of factors such as satisfaction with wages, hours and working conditions[26]. There are almost as many lists of the key factors underlying QoWL as there are authors (e.g.[27],[28])The suggestion that QoWL might vary between groups of workers has threaded its way through the literature, as, for example, illustrated in research which has identified a number of factors contributing to poor quality of working life in nurses[29]. Sirgy et al.[30] suggested that the key factors in QoWL spring from need satisfaction based on job requirements, work environment, supervisory behaviour, ancillary programmes, and organizational commitment. They proposed that higher QoWL reflected satisfaction of these key needs through resources, activities, and outcomes stemming from participation in the workplace. Maslow’s needs[31] were seen as relevant in underpinning this model, although the relevance of non-work aspects is played down, as attention is focussed on quality of work life rather than the broader concept of quality of life.More recently, a number of key factors underlying QoWL have been put forward on the basis of an analysis of a small sample for the Institute for Employment Studies, with the question items being drawn from themes in the literature[32]. These dimensions highlight the relevance of an individual’s pay and benefits, their relationships with their manager and colleagues, the nature of their work and the way it is organised.These attempts at defining QoWL have included theoretical approaches, lists of identified factors and correlational analyses, with opinions varying as to whether such definitions and explanations can be both global, or need to be specific to each work setting. The main theoretical models underlying the development of the concept of QoWL have been summarised as: The Transfer Model (or Spillover Effect); The Compensation Model; The Segmentation Model and The Accommodation Model[33].The Transfer Model or Spillover Effect[34] emphasises the positive links between work and non-work areas of life. The Compensation Model,[35] on the other hand places emphasis on the way in which an individual might seek to seek outside work that which is absent in the work setting. Thus, a tedious job might be held by someone who actively seeks excitement through their hobbies and interests.The Segmentation Model[36] proposes that work and homelife do not substantially affect each other, whilst the Accommodation Model[37] envisages an active variation of investment from work to home and vice versa to balance demands in each sphere.Loscocco & Roschelle[38] have, however, highlighted the degree to which these models have lacked both supporting evidence and universal acceptance, as researchers have continued to disagree on the best way to conceptualise QoWL. The story of the development of the concept of QoWL hitherto has only recently begun to include more rigorous methods of empirical research focusing on identifying key factors and explaining the relationships between them. Theories need to be tested if they are to be refined, and the more central role of statistical analysis of findings to aid understanding of QoWL is perhaps somewhat overdue.

5. How Can the Concept of Quality of Working Life be Useful in the Police Setting - does it Matter?

- Collins and Gibbs[39] conducted a survey of a population of 1206 police officers and concluded that: “occupational stressors ranking most highly within the population were not specific to policing, but to organisational issues such as the demands of work impinging upon home life, lack of consultation and communication, lack of control over workload, inadequate support and excess workload in general” (p. 256). The relevance of factors such as the home-work interface, control at work and stress at work in the police is not new. However, the identification and assessment of the most important factors underpinning quality of working life is new, may offer a basis for more effective interventions to improve the experience of employees in the police setting.Regular assessment of the broad elements of Quality of Working Life can provide organisations with relevant information about the welfare of their employees, including as job satisfaction, general well-being, work-related stress and the home-work interface. A valid assessment of these key factors provides the opportunity for employers to reduce costs associated directly and indirectly with poor Quality of Working Life. It has been suggested that costs associated with poor staff QoWL may well be substantial; Worrall and Cooper[40] reported that a low level of well-being at work is estimated to cost about 5-10% of Gross National Product per annum.The recent publication of the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)[41] calculated that the typical annual cost of mental ill health to an organisation with 1000 employees can be estimated at £753,950. They suggest that attention to improving the management of mental health in the workplace, including identification of problems could produce annual savings of £226,200. The NICE guidance suggests that potential savings through targeted assessment and intervention can be in the order of 30%.The relevance of Quality of Working Life to endeavours to reduce such costs, however, has hitherto been limited by the poor assessments available. What is required is a valid assessment of Quality of Working Life as a basis for targeted, and therefore, potentially, cost-effective interventions.

6. How can Quality of Working Life be Measured?

- There are few measures of quality of working life, and of those that exist, few have evidence of validity and reliability and there is a very limited literature based on peer reviewed evaluations of the available assessments. A recent statistical analysis of a new measure, the Work-Related Quality of Life scale (WRQoL)[1], indicates that this assessment device should prove to be a useful instrument. The Work-Related Quality of Life scale was been developed over several years from an initial collection of 200 questions gathered from existing surveys or generated based on theoretical requirements, which were then reviewed by an expert panel to give an item pool of 61 questions. The questionnaire was then given to over 1000 employees of the UK National Health Service, and EFA and CFA on the two halves were undertaken. The data sets were combined (N = 953) to confirm a 6 factor structure with 23 items (Overall C’s α = .91) and showed a ‘good’ model fit for the ‘Work-Related Quality of Life’ (WRQoL) scale which appeared to be a valid and reliable scale with good psychometric properties. Subsequent analyses with other public sector workers have similarly found good support for the measure[42].The WRQoL measure uses 6 core factors to explain most of the variation in an individual’s quality of working life.The Career & Job Satisfaction factor assesses general satisfaction with the job and with career development, whilst the Working Conditions factor focuses evaluates level of satisfaction with the physical working environment and conditions and is affected by respondents’ views as to whether or not they have the right tools and equipment to get the job done.The General Well-being factor assesses key aspects of psychological and physical well-being, such as happiness; wellness, and the Home-Work Interface factor scores reflect respondents’ views about the degree to which the organisation understands and tries to help them with pressures outside of their work.The fifth factor addresses Stress at Work, and provides a measure of Level of work-related stress, drawing upon the respondents’ assessment of the extent to which work pressures and demands as acceptable and not excessive or ‘stressful’.Involvement in decision making is assessed by the final WRQoL factor, Control at Work.Benchmark data sets and psychometric norm groups have been developed for the WRQoL based on surveys of, for example, UK Higher Education workers, Unions and NHS Trusts. Thus WRQoL survey results can be interpreted in the light of relevant benchmarks. The results of assessment of WRQoL sub-factors can be interpreted both within and between organisations to provide context, and so support interpretation of the absolute and relative sub-factor results. Thus a score, for example, on the Home-Work Interface subscale might be interpreted in terms of other departmental scores on that subscale within an organisation (e.g. a road policing unit and Criminal Investigation Department staff), and/or it might be compared with scores on that subscale in other organisations (e.g., other police forces).A police service may wish to better understand the variability in the overall or sub-factor aspects of quality of working life within its own staff groups, and it may wish to benchmark those QoWL scores against other police forces. The comparison of scores between departments, organisations or even groups of workers in different industries requires confidence in the assessment process, the measure and the benchmarking. A recent preliminary study offers the first step in developing a benchmark on the WRQoL specific to the UK police service, and is presented in outline here.

7. Assessing Quality of Working Life in the Police; Some Preliminary findings

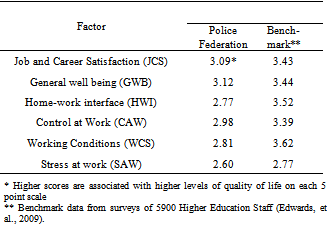

- A survey was undertaken of quality of working life of Police Federation members of a UK county force which included questions from the Work-Related Quality of Life scale (WRQoL) [1]. 3567 Police Federation members were asked to participate in an online survey. The participants were varied ranks within the police force, including, police staff, Police Constables, Sergeants, Inspectors and above (Inspector and Chief Inspectors were grouped together to ensure anonymity given fewer officers at these levels). 615 participants completed the online questionnaire, giving a response rate of 17.24%. Some data were excluded from analysis due to incomplete sets of responses. The final sample consisted of 533 respondents. Items of the WRQoL survey are measured on a five point Likert scale (1-Strongly Disagree, 5-Strongly Agree)[1].Table 1 provides a summary of the preliminary findings for the whole sample by Work-Related Quality of Life subscale. The data is compared to a large scale bench mark data from surveys of 5900 Higher Education Staff [43].Whilst these findings provide a useful snapshot, some caution should be exercised in interpretation of this data, given sample size and percentage response rate. It is hoped that further police staff surveys will allow development of a larger police benchmark data set.

|

8. Conclusions

- The links between positive and negative work experiences and the psychological well-being or perceived quality of life of police officers has been clearly demonstrated (e.g.:[10],[44]), with particular emphasis on the relationships between work and family and job and life satisfaction. Hitherto, however, research has been hamstrung by the absence of a valid and reliable measure of quality of working life which could provide the information required for effective, targeted interventions.Following a rigorous process, six key aspects have been shown within the Work-Related Quality of Life scale (WRQoL)[43] to effectively reflect the key factors underlying variations in the experience of individuals in the workplace. The valid and reliable assessment of the broad concept of quality of working life offers the opportunity for police services to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the environments in which their staff work, and thereby plan targeted interventions, the effects of which can in turn be assessed by repeated administration of an appropriate measure.Further study of the WRQoL is required, as is development of a police benchmark data set, but it can be argued that a measure of quality of working life is now available for the evaluation of police service staff work experience, so that cost-effective programmes can be designed and implemented to improve the quality of working lives of police service staff.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML