-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(2): 112-120

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130302.08

Examining Pre-Internship Expectations among Employers on the Students’ Characteristics and Internship Program: The Empirical Study of Malaysian Government-Linked Company’s University

Juliana Anis Ramli 1, Khairul Nizam Surbaini 2, Mohd Rizuan Abdul Kadir 1, Zulkifli Zainal Abidin 1

1Department of Accounting, Universiti Tenaga Nasional, Muadzam Shah, 26700, Pahang, Malaysia

2Department of Marketing & Entrepreneur Development, Universiti Tenaga Nasional, Muadzam Shah, 26700, Pahang, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Juliana Anis Ramli , Department of Accounting, Universiti Tenaga Nasional, Muadzam Shah, 26700, Pahang, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study attempts to investigate the what the employers expect on the students’ characteristics and the internship program itself, before the internship period. It also would like to measure whether there are significant differences between the demographic factors of employers and their expectations about the students’ characteristics and the internship program. The primary data collection was through self-administered questionnaires which were distributed to a sample of 134 firm employers of 165 students that provide internship training in their workplace to the final year accounting students. Factor analysis and multivariate ANOVA have been employed in order to meet the objectives of the study. The results reveal that there are three (3) dimensions underpinning for each scale of students’ characteristics and the internship itself which are the employers expecting before the accounting undergraduates undergoing for the internship period. Most of the employers ranked the future career development as the most important and relevant to the undergraduates to secure for future employment. Further, some significant differences between demographic factors of employers and the dimensions of employers’ expectation are identified and discussed.

Keywords: Employer, Expectations, Students’ Characteristics, Internshiphip, Government-Linked Company, University, Malaysia

Cite this paper: Juliana Anis Ramli , Khairul Nizam Surbaini , Mohd Rizuan Abdul Kadir , Zulkifli Zainal Abidin , Examining Pre-Internship Expectations among Employers on the Students’ Characteristics and Internship Program: The Empirical Study of Malaysian Government-Linked Company’s University, Management, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 112-120. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130302.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The aftermath of the Asian economic crisis in 1997 had a tremendous impact on many aspects especially on Malaysian economy and even the job market opportunities also had been dwindled. In fact, the Malaysian government has reduced its sponsorship for the number of students who obtained excellent academic performance in secondary education level to pursue their studies abroad. Due to its limited educational funds to support these students, many of them were sent to pursue their tertiary education level in local universities. As a result, there were number of universities and colleges mushrooming during at that time in order to accommodate the huge number of students hold in a variety of disciplines. Overall, 20 public universities as well as 18 private universities including the establishment of government-linked companies’ universities such as Tenaga Nasional University (wholly-owned by the Malaysian largest utilities service provider, Tenaga Nasional Bhd), Multimedia University (wholly-owned by the Malaysian largest telecommunication provider, Telekom Malaysia Bhd) and Petronas University (which wholly- owned by the Malaysian largest oil and gas provider, Petronas Bhd) in the year 1997 that offered wide range of study options, indicating that the increasingly demand on sophisticated education in tandem with the requirement of the government to churn out more number of future professional workforces. As the global shifts to the new paradigm, the remarkable changes and rapid technological development in the business environment have resulted the employer’s expectations of hiring candidates have also increased. Accounting profession nowadays has become more complex to face the global challenges ahead than it was in the last decades. According to Siegel and Sorenson (1999), the roles of accountants have been escalated and the stereotype of accountants as ‘bookkeepers’ or ‘number crunchers’ are no longer suited in a world of immense competition, but their attributes are expected to bring value to the organisation through broader tasks such as decision-making, strategic planning, gurus of knowledge management and even provide value-added services to the clients (Howieson, 2003). In a light of that, candidates are prevalent incredibly outstanding in their academic achievement, but the required diverse range of soft skills such as communication, leadership, including intra-personal skills are found still lacking in most candidates from the employers’ perspective in order to be competent and competitive with the other candidates in the job placement (Muda, Che Hassan and Abd Samad 2009). However, many employers have expressed their disappointment that the graduates were unable to demonstrate the required soft skills and the said qualities as well as in-depth understanding of accounting which are perceived as extraordinary factors and pertinent from the eyes of employers, as a result, abundant graduates are failed to be absorbed in the job market. Soft skills deficiencies are identified as major factor that contributes to the unemployment issue (Hairi, Ahmad Toee and Razzaly, 2011). On average, the unemployment rate from 1998 until 2012 was reported at 3.34 per cent, and recently the employment rate last reported in August 2012 was relatively low at 2.8 per cent (Department of Statistics, 2012). The mismatch between what the graduates have learned and their attributes developed during studying in the university and to meet the increasing demand of employers, has led the Ministry of Higher Education has taken another step to put forward a greater attention to reduce the unemployment rate by improving the education system and curricular activities, such as the introduction of internship or industrial practical training in most Malaysian universities/colleges. It requires the accounting academician to review and update the syllabus of accounting-related subjects as well as its curriculum with the latest development or issues that necessarily to be placed on in parallel with the employers’ realistic expectation in order to face greater competition and challenges in the business environment. Accounting educators play significant role in guiding and committed to deliver the knowledge to future accountants that adequately equipped with the knowledge and skills in relation to the international requirements (Ahmad, 2012).Beside portraying a good image for the company, the employers are also looking for the recent graduates that have a wider range of skills and positive attitudes to bring that value to their organization. This can be supported from the past literatures in the sense that the right qualification together with the valuable soft skills and good attitudes are the elements that should be embedded among undergraduates in order to get easily being employed upon their graduation (see Ismail, 2011; Mohd Zabid and Ling, 2003; Ingbretsen, 2009; Howieson, 2003). Hairi et.al. (2011) suggest that generic skills coupled with technical skills are seen very important in the working place in order to meet the employer’ expectations In addition, both skills also can be acquired through pre- real working experience in the workplace which cannot be acquired in the classroom learning, but through an experiential education i.e. internship program. The internship program is perceived as an indispensable path towards securing future expectation career (Chau Mai, 2012) and perfect blend of gaining valuable learning and experiences that ultimately wide- range of skills can be gathered and developed during this worthwhile period. However, Knight and Yorke (2003) have different perceptions on the skills developed during practical training among students. They perceived that it can be treated as more on ‘social practices’ and the level of employability is depending on how the students absorbed that knowledge and practice well on the such assignment or work given by the employers. As lifelong learners, the transition from the learning environment such as university/ college to the alienated-like surroundings in the workplace, has given complex perception and anxiety to the students in order to get acquainted with the different learning environment. This experiential education (internship) helps to reduce the students’ work apprehension before entering the real working environment (Knouse, Tanner and Haris, 1999) and escalates the path for future learning (Knight and Yorke, 2003). An internship is a structured practical training undertaken by students before completing their studies, and is viewed as a smooth transition period from the academic world to the working environment (Muhammad et al., 2009). According to Cook, Parker and Pettijohn (2004), internship assists the students to better equipped themselves with the enhancement of interpersonal skills and personal maturity, and the students who have internships been more likely to find their job quicker than their counterparts who did not have an internship experience (Henry, 1979). Besides, the internship is regarded as a mechanism to explore the one’ self- strengths and weaknesses in adapting to the competitive environment in the workplace (Callanan and Benzing, 2004) and allow the acquisition of relevant job-related skills (Garavan and Murphy, 2001). According to Chelvarajasingam (2012), most employers are looking for candidates that equipped themselves with a high level of confidence and being more advanced in critical thinkings and problem-solving skills in order to adapt themselves to the demands of the working world. There are few studies which acknowledge the employers’ expectation on what skills to be required of graduates from the views of students and various of employers (Kavanagh and Drennan, 2008), investigating the effects of graduates characteristics on the chance of employment upon graduation (Ismail, 2011), and seeking for accounting graduates’ characteristics which perceived to be important and pertinent to the employers’ requirements (Muda et.al., 2009). Several past studies perceived that the internship provides positive development for the students, employers and institutions as well, and yielded with a number of favourable impacts and future outcomes. In fact, average-performing student interns are more likely receive full-time job offers while the outstanding-performing students have their chances to get full employment with better salaries offered (Gault, Leach and Duey, 2010). However, an investigation on employers’ expectations towards undergraduates who are going to have their internship (pre-interns) and the function of internship for their future employment should be taken into high consideration and important whether they are adequately prepared themselves before stepping into the internship period. Since this area of study is found still lacking in the existing literatures, hence warrants us to conduct this research. In this study, the researchers would like to reach to the following research questions:1) What are the dimensions underpinning the scale of students’ characteristics that employers are expecting from the undergraduates, before an internship program?;2) What are the dimensions underpinning the scale of the internship program that employers are expecting from the existence of internship program itself, before an internship program?;3) Are there any significant differences between employers’ demographic factors such as gender, races, recruiting experience and supervisor’s experiences, and the dimensions underpinning the scales of the employer’s expectations on students’ characteristics and the internship program, before an internship program?This study attempts to investigate the dimensions underpinning the scales of employers’ expectation on students’ characteristics and the internship program, before an internship program. It also would like to examine the significant differences between the employers’ demographic factors and the dimensions underpinning of both expectation scales among the employers of accounting undergraduates in Malaysian GLC’s university.The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the past literatures with regard to the employers’ expectation on students’ characteristics i.e. required skills needed by employers and internship program, and the development of hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the instrumentation, samples and sampling procedures. Section 4 presents the analysis of findings and discussion of the results. Ultimately, Section 5 concludes and sets out the limitation and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

- The employability and graduates’ skills have been widely debated and discussed since last decades. A number of studies cast a broad discussion on the importance of the employability skills and relevant job-related skills to be developed and embedded among graduates when entering into the accounting profession. Due to intense global competition among business environment, the roles of accountant become closely scrutinized by the public to be ethically and technically proficient in the job matter. The employers, are the most significant persons who responsible to hire those candidates that have the qualities and strong characters in terms of their academic achievement, capabilities and skills in order to keep pace with the challenges in the profession. One of the ways those implicit capabilities and skills are gained is through education (International Federation of Accountant, IFAC 1996). In fact, several researchers have pointed out that even though the accounting profession requires the candidates to be technically proficient in in their prospect employment, i.e. making a sound decision and strategic planning that very much important to serve for the organisation and stakeholders, however tacit knowledge and soft skills that have been developed especially during the internship period are regarded much more important in order to succeed and securing a commitment in the future job (Aiken, Martin and Paolillo, 1994; Watty, Cahill and Cooper, 1998; Eberhardt and Moser, 1997).There are several studies that have undertaken to identify the necessary skills and characteristics of graduates from the employers’ perspectives. According to Kavanagh and Drennan (2008), students are regarded as life long learners and they must be persistent to keep on continually learning on new things as the most important skill for the future job. In addition, Kavanagh and Drennan (2008) have found that most employers are expecting must-have top three skills among graduates when they are entering the real working environment which are analytical/problem solving skills, real life experience and basic accounting skills, besides other job generic skills such as communication skills, written skills and even teamwork and professional skills. Jackling and De Lange (2009) found that employers are seeking for candidates that have equipped themselves with a wide-range of generic skills which cannot be gained through classroom learning. On top of that, they added that those skills that are perceived as the most essential for the graduates for their entry into the profession are team skills, leadership capabilities, communication skills and the interpersonal skills. On the other hand, from the findings of Wye and Lim (2009) suggested that although undergraduates of Malaysian private universities are sufficiently competent in the said qualities and employability skills, however certain skills are still found discrepancy from the eyes of employers those are analytical/problem solving skills, communication skills and decision-making and negotiate with clients. For some employers, as far as the business environment evolved and become more complex are concern, they put greater emphasis on the graduates’ abilities to work with other people coupled with their strong characters rather than contented in their academic performance.An internship provides huge impacts to the level of employability of graduates upon their graduation. Previous researchers have established the three main reasons as affecting the graduates’ lack of employability, which are a weak command in English, poor attitude and personality, and unrealistic expectations of salaries and benefits (The Star, August 21, 2005). Internship is perceived as a credible means to land a first job (Cannon and Arnold, 1998; Lam and Ching, 2007), positively increase the students’ knowledge base and inspire their motivation to become professionally before entry into the marketplace (Beard, 1998), provides a tacit knowledge (Nonoka and Takeuchi, 1995), and can provide a significant means for bridging the gap between the classroom and the business environment (Beard, 1998). In the context of internship in accounting education, Beck and Halim (2008) explored the impact of internships for accounting students, and identified that among the learning outcomes of the internship, the two factors, self-efficacy/ interpersonal skills and computer skills were considered as significantly very important for their future career development. In addition, the acquisition of those skills was supported by completing a logbook (useful to expedite ‘Reflective Learning’) and interestingly, they also found that a realistic experience of working under pressure in the accounting internship influenced the students to consider alternative professions. Furthermore, this experiential education also benefits to the students in the sense of providing valuable job experiences from hiring organisations and consequently building up students’ self-confidence when a full-time employement is secured (Knousse, Tanner and Harris, 1999). This view has also been supported by Paisey and Paisey (2010) from their findings that work placement or internship is regarded as a channel to develop personal transferable skills. In the Malaysian context, Muhammad et al. (2009) found that students did not benefit from the internship attachment due to difficulty of adaptation to the working environment and this difficulty is rooted from not being treated as regular employees and thus they were not being given appropriate and specific tasks that related to job settings and experience exposure. In contrast, Muda et.al. (2009) found that there is a convergence of students and employers’ view in the notion that work quality, work attitude and punctuality are significantly important in recognising the requirement characteristics by the employers. Furthermore, she added that the employers have different expectations about candidates’ characteristics to be possessed to enter the world of work, such as dependability, initiative to enhance job performance and being open-minded for any constructive criticism. Meanwhile, interesting to know that the students overvalues those interpersonal skills, creative thinking, research skills and work attendance as to meeting the demand of the employers.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Instrumentation

- This study adopted a quantitative research design, where a self-administered questionnaire was developed in order to meet the objectives of the study. The questionnaire items that related to employers’ expectation towards students’ characteristics and the internship itself were adopted from several existing literatures, such as Schumutte (1998), Lam and Ching (2007), Paisey and Paisey (2010), and Kandasamy and Ancheri (2009). The structured questionnaire consisted of three sections. Section one collected the socio-demographic data of respondents (employers) such as gender, age,race, type of company, years of recruiting experience, years of supervisors’ experience, and location of the company. Section two examined the respondents’ expectations on students’ characteristics which is consisted of 15 variables, for instance, one of the variables on students’ characteristics “Verbal communication skills”, the respondents (employers) were asked to provide their expectation on the importance of the students’ characteristics to be prepared before the internship program, measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranged from ‘Not Important’(1) to ‘Extremely Important’ (5). Meanwhile, section three examined the employers’ expectation on the internship program that comprised of 19 variables. For instance, for one of the variables in internship perception “train the students in developing new skills”, the respondents were asked to provide their expectations on the internship whether it effectively trains the students to develop new skills during the internship period. The variables in this section are measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranged from ‘strongly disagree’(1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5).

3.2. Sampling and Sampling Procedures

- The sampling frame of this study consisted of the industry worksite employers/supervisors who were responsible in monitoring and supervising the GLC’s university’s accounting student interns. The questionnaires were distributed to the respective employers/supevisors through the mail or walked-in to their offices. The respective companies were identified through faculty members who were managed in monitoring and also to acknowledge the internship procedures as well as the company placement for the student interns. Altogether, 165 questionnaires were distributed and 134 were collected from the respondents, representing a response rate of 81.2 percent. All the collected questionnaires were perfectly answered by the respondents and the researchers found that there were no incomplete questionnaires received from the respondents. Scale reliability analysis was used to measure the internal consistency of the internship perceptions construct, and a generally agreed upon lower limit for the Cronbach’s alpha was set at 0.70 (Coakes, Steed and Price, (2008)). In order to assess the normality distribution for a particular variable, a normality test was used using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. In addition, the researchers also have conducted a factor analysis in order to find a smaller number of factors that attributed to the employers’ expectation towards the students’ characteristics and the usefulness of the internship program to the students. Principal components (PC analysis) and VARIMAX rotation method were used to factorise the overall 34 employers’ expectation variables into a set of composite factors, eigenvalues equal or greater than 1.0 were considered significant, and chosen for interpretation, while factor loadings equal to or greater than 0.3 were chosen for analysis since this matrix is suitable for factoring (Juat Hong, (2007); Coakes et al., 2008). Meanwhile, multivariate analysis was conducted in order to examine whether there were significant differences exist between demographic factors i.e. gender , recruiting and supervisor’s experience and the dimensions of the scales of students’ characteristics and the internship program from the employers’ expectations (Palaniappan, 2011; Coakes et al., 2008).

4. Discussion of Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Inferential Statistics

4.2.1. Factor Analysis

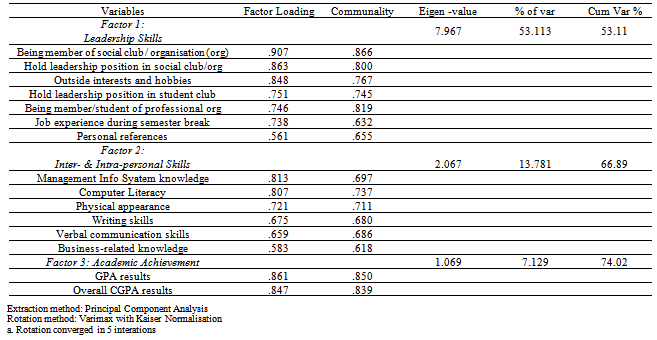

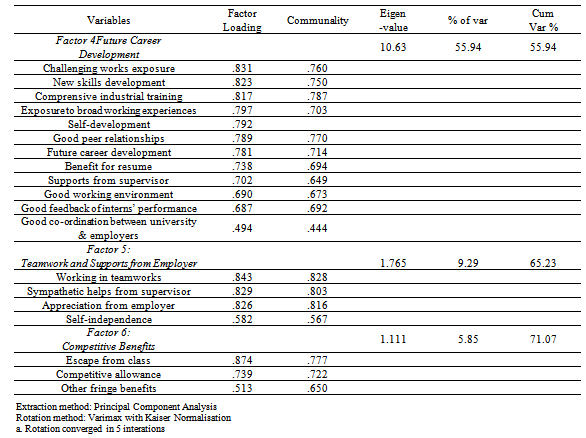

- Two principal component analysis followed by VARIMAX rotation were employed separately to analyze the 15 variables of employers’ expectations before internship began, on the students’ characteristics to be capable in handling works during internship period and 19 variables on their expectations on the usefulness of an internship program for the students, based on the Eigenvalues of 1 and above, and factor loadings of 0.3 and greater. Results as shown in Table 2 and 3, each suggests that 3 factors (or dimensions) have been generated and developed from its 15 variables (students’ characteristics) and 19 variables (internship) for interpretation of the scales. In Table 2, they explained 74 percent percent of the expectation’ variance with a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of the sampling adequacy of 0.907, and the Barlett Test of Sphericity of 4695.88 (p = 0.00) for respondents’ expectations on the students’ characteristics of the GLC’s university before undergoing for an internship.

|

|

|

4.2.2. Multivariate (MANOVA) Analysis

- Table 5 and 6 summarise the significant differences exist between the demographic factors and certain dimensions of the employers’ expectation of the GLC’s university’s students, before internship. Among 6 dimensions, only Factor 5 (Teamworks and support from employers) has significantly different from gender expectation, in which female employers expected more on the students’ capabilities to work in groups. In addition, female employers mostly found affectionate in nature than its counterpart as they are willing to help the future interns if they asked for guidance from their employer/supervisor. This finding can be advocated by Kavanagh and Drennan (2008) that employers ought to be rationale in expecting higher order skills from the students since the students are still in the learning and development process and all the work-related skills required only can be acquired if they are well-guided during the internship process. Furthermore, there are significant differences exist among races in terms of pre-internship employers’ expectation, that Malay employers expected that internship program would be beneficial for the students as a future career development (Factor 4, m = 46.492). Meanwhile, Indian employers had the highest expectations on Factor 5 (Teamworks and support from employers) and Factor 6 (Competitive benefits) toward students of the GLC’s university, than other races of the employer. This could be probably that besides learning process, students also are expected to earn money from hiring organisation that they indirectly assist the organisation to ensure the job assigned is getting done within the stipulated time.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

5. Conclusions and Future Researches

- This empirical investigation focuses on analysing the dimensions or factors underpinning the scales of students’ characteristics and the usefulness of internship for the students, from the employers’ expectation before commencing the internship. Furthermore, this study also would like to examine whether the significant differences among demographic factors on the respective dimensions do exist. The findings of this research regarding the employers’ expectation towards the future interns of the Malaysian GLC’s university are consistent with the internship-based research suggesting that internship play a vital role in escalating the prospects of interns future employment Besides, students are expected to embed themselves with the valuable soft skills such as leadership and interpersonal skills before commencing the internship in the company placement in order to be adequately prepared to face the challenges in the pre-world of working environment. In a nutshell, academic achievement solely does not guarantee to fulfil the employers’ expectation on measuring the intern’s competencies while being in this experiential education period. It is interesting to know that demographic factors of the employers have also contributed to the significantly different to their expectations. Female employers are predominantly and affectionately in nature expected from their future interns to work together with other staff dealing with the job matters and seek for the helps and guidance from the senior staff. Meanwhile, the finding suggests that Malay employers have put much their expectation on the internship program in the notion that this experiential education is beneficial to the future interns from the aspect of elevating their chances in getting the future prospect jobs and improving self-development. On the other hand, the significant differences between the employer’ races still exist in terms of their expectation in which Indian employers were empirically found that they were far more emphasised on their expectations in the notion that the internship significantly impact on integrating the ideas and skills through teamworks among the employees and the future interns for maintaining the firm’s reputation. Through the interns’ contribution in completing the daily task given and simultaneously facilitating the firm in the work process, the Indian employers also expected that the future interns can earn ‘pocket money’ in return for their valuable contribution to the company. However, this study fails to find the evidence in assessing the significant gap exists in other dimensions. Surprisingly, those employers or supervisors who had less than three years experience both in supervising and hiring student interns were more expecting on the dimension of leadership skills to be equipped before entering the internship period from their respective internees. This, may perhaps indicate that this group of employers / supervisors was likely to expect and preferred the potential student interns who embedded themselves with strong characteristics and being capable to solve any problem/issue independently. However, there is no empirically found the significant differences between the demographic factors and the employers’ expectations in other dimensions. From the practical implication, perhaps with these expectations from the employers, it can send a strong and significant message to the educators in the need to incorporate accounting curriculum with work-related learning into programs so that those skills required can be developed and inculcated among the students since the tertiary level of education. It is important to note that the university/college is vital to collaborate with professional accounting bodies to organise such significant activities i.e. events or training for the students as life-long learners in relation with the preparation for the predicted future internship and even the complexity of the work world. Perhaps, revision of the syllabus of accounting subjects among the educators to meet the changes and current demand of the accounting environment plays critical role in order to create the awareness among the educators to provide the relevant and sufficient coverage of the syllabus so that a strong foundation can be developed for the education system in producing the graduates with required qualities. Finally, it is also hoped that the research can be extended to a wider scope of sample such as involving employers of accounting students from other Malaysian universities (including private and public), investigating employers’ perceptions whether the performance and characteristics of the students would lead to better chances of getting secured employment Besides, a study whether the students meet the expectation of employers, before and after the internship also can be examined and perhaps other factors/dimensions can be identified through other qualitative method of research such as interview to provide an insightful and fruitful future contribution to the existing literature in this area of accounting education.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to acknowledge and to express our deep and heartfelt gratitudes to our family, participating employers and students, encouraging friends who willing to provide us with the fruitful ideas and their kind cooperation in making this research to be successful.

References

| [1] | Adlin, “Education System Not Producing Thinking Graduates”, Retrieved from on 20 October 2012, 2012. |

| [2] | Ahmad, M.N., giving his speech in National Accounting Educators Symposium, published in Accountants Today, MIA, September/October 2012, vol.25, no. 5, pp. 10-11, 2012 |

| [3] | Aiken, M.W., Martin, J.S., Paolillo, “Requisite Skills of Business School Graduates:Perception of Senior Corporate Executives”, Journal of Education for Business, vol.69,no.3, pp.159-162, 1994. |

| [4] | Beard, D.F., “The Status Of Internships/Cooperative Education Experiences In Accounting Education”, Journal of Accounting Education, vol. 16, no. 3/4, pp. 507-516, 1998. |

| [5] | Beck, J.E., Halim, H., “Undergraduate Internships in Accounting : What and How do Singapore Interns Learn from Experience?”, Accounting Education: An International Journal, vol.17, no.2, pp.151-172, 2008. |

| [6] | Callanan, G. and Benzing, C., “Assessing the Role of Internship in the Career-Oriented Employment of Graduating College Students”, Journal of Education and Training, vol.46, no.2, pp.82-89, 2004. |

| [7] | Cannon, J.A., Arnold, M.J., “Student expectations of collegiate internship programs in business: A 10-year update”, Journal of Education for Business, vol.73, no.4, ABI/INFORM Global, pp. 202-205, 1998. |

| [8] | Chau Mai, R.,”Developing Soft Skills in Malaysian Polytechnic Students: Perspectives of Employers and Students”, Asian Journal of Management Sciences and Education, vol.1 , no.2, pp.44-51, 2012. |

| [9] | Cook, S.J., Parker, R.S., Pettijohn, C.E., “The perceptions of interns: A longitudinal case study”, Journal of Education for Business, vol.79, no.3, ABI/INFORM Global, pp. 179-185, 2004. |

| [10] | Chelvarasingam,R., “Education System Not Producing Thinking Graduates”, Retrieved from on 20 October 2012, 2012. |

| [11] | Department of Statistics. Retrieved from on 25 October 2012. |

| [12] | Eberhardt, B.J., Moser, S., McGee, P., “ Business Concerns regarding MBA education: Effect on Recruiting”, Journal of Education for Business, vol.72, issue 5, 1997. |

| [13] | Gault, J., Leach, E., Duey, M., “Effects of Business Internships on Job Marketability: The Employers’ Perspective”, Education + Training, Vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 76-88, 2010. |

| [14] | Garavan, T.N., Murphy, C.., “The Co-Operative Process Education Process and Organisational Socialization: A Qualititative Study on Students Perception of Its Effectiveness”, Education + Training, Vol. 43, issue 6, pp. 281-302, 2001. |

| [15] | Hairi, A.F., Ahmad Toee, M.N., Razzaly, C.W., “Employers’ Perception on Soft Skills of Graduates: A Study of Intel Elite Soft Skill Training”, International Conference on Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (ICTLHE 2011), pp.1-8, 2011. |

| [16] | Howieson, B., “Accounting Practice in the Millenium: Is Accounting Education Ready to Meet the Challenge?”, The British Accounting Review 35, pp. 69-103, 2003. |

| [17] | Henry, N. “Are Internship Worthwhile?” Public Administration Review, pp. 245-247, 1979. |

| [18] | International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), “Prequalification Education, Assessment of Professional Competence & Experience Requirements of Professional Accountants”, New York: Education Committee, 1996. |

| [19] | Ingrebetsen, R.M., “What Employers Really Look For When Hiring a College Graduate in 2009?”, Retrieved from: on 29 October 2012. |

| [20] | Ismail, N.A., “Graduates’ Characteristics and Unemployment: A Study Among Malaysian Graduates”, International Journal of Business and Social Science, vol. 2, no. 16, 2011. |

| [21] | Jackling, B., De Lange, P., “Do Accounting Graduates’ Skills Meet the Expectations of Employers? A Matter of Convergence or Divergence”, An International Journal of Accounting Education, vol. 18, issue 4-5, pp. 369-385, 2009. |

| [22] | Hong, T. J. (2007). Statistical Techniques and Business Research: A Practical Approach, 2nd edition, Prentice Hall, Malaysia. |

| [23] | Kavanagh, M.H., Drennan, L., “What Skills and Attributes Does An Accounting Graduate Ned? Evidence from Student Perceptions and Employer Expectations”, Journal of Accounting and Finance, vol. 48, issue 2, pp.279-300, 2008. |

| [24] | Knouse,S.B., Tanner, J.R., Harris, E.W., “The Relation of College Internships, College Performance, and Subsequent Job Opportunity”, Journal of Employment Counselling, vol. 36, issue.1, AB/INFORM Global, pp.35-43, 1999. |

| [25] | Knight, P.T., Yorke, M., “Employability and Good Learning in Higher Education”, Teaching in Higher Education, vol.8, no. 1, pp. 3-16, 2003. |

| [26] | Lam, T., Ching, L., “An Exploratory Study of an Internship Program: The Case of Hong Kong Students”, Hospitality Management, vol. 26, pp.336-351, 2007. |

| [27] | Mohd Zabid, A.R., Ling, C.N., “Malaysian Employer perceptions About Local and Foreign MBA Graduates”, Journal of Education for Business, pp.111-117, 2003. |

| [28] | Muda, S., Che Hassan, A., Abd Samad, R.N., “Requirements of Soft Skills Among Graduating Accouting Students: Employers and UiTM Students’ View”, Technical Report, Institute of Research, Development and Commercialization , Universiti Teknologi MARA, pp.1-24, 2009. |

| [29] | Muhammad,R., Yahya, Y., Shahimi, S., Mahzan, N., “Undergraduates Internship Attachment in Accounting : The Interns Perspective,” International Education Studies, vol. 2, no.4, pp. 49-55, 2009. |

| [30] | Nonoka, I., Takeuchi, H., “The Knowledge Creating Company : How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation” , New York, Oxford University Press, 1995. |

| [31] | Paisey, C., Paisey, N.J., “Developing Skills via work Placements in Accounting: Student and Employer Views”, Accounting Forum, vol. 34, pp. 89-108, 2010. |

| [32] | Palaniappan, A.K., “Penyelidikan dan SPSS (PASW)”, Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2009. |

| [33] | Sigel, G., Sorenson, J.E., “ Counting More, Counting Less” Transformations in the Management Accounting Profession – The 1999 Practice Analysis of Management Accounting”, The Institute of Management Accountants. |

| [34] | Wye, C.K., Lim, Y.M., “Perception Differential between Employers and Undergraduates on the Importance of Employability Skills”, International Education Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, pp.95-105, 2009.[online available:] |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML