-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(2): 105-111

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130302.07

Multiple Directorships, Board Characteristics and Firm Performance in Malaysia

Rohaida Abdul Latif 1, Hasnah Kamardin 1, Kamarun Nisham Taufil Mohd 2, Noriah Che Adam 1

1School of Accountancy, College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, 06010, Kedah, Malaysia

2School of Economics, Finance and Banking, College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, 06010, Kedah, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Rohaida Abdul Latif , School of Accountancy, College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, 06010, Kedah, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of the study is two-fold. First, the study examines the extent of multiple directorship practices of Malaysian public listed companies. Secondly, the study assesses the relationship of several board characteristics with firm performance. Using a sample of 132 companies in 2008, the result shows that almost 90% of directors of Malaysian public listed firms have between 1 to 3 directorships. The multiple directorships affect firms’ market performance positively but not significantly. Ex-government officials and founders have positive and significant influence on performance. Family ownership is significant and has U-shaped relationship with performance. The findings to some extent have policy implication to corporate governance practices.

Keywords: Multiple Directorship, Corporate Governance, Ex-Government Officials, Firm Performance

Cite this paper: Rohaida Abdul Latif , Hasnah Kamardin , Kamarun Nisham Taufil Mohd , Noriah Che Adam , Multiple Directorships, Board Characteristics and Firm Performance in Malaysia, Management, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 105-111. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130302.07.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Recent development in the corporate governance literature expresses concerns on the effectiveness of the roles played by the board of directors[1]. Principle 4 of the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance 2012 expresses that the board of directors should devote sufficient time to carry out their duties effectively and be careful before accepting new directorship as more directorships might impinge effective discharge of their responsibilities. In Malaysia, multiple directorships of independent directors are found to be common among listed firms as in[2].This practice is not surprising because of the high limit of directorships allowable to directors. Section III of the Bursa Malaysia Practice Note no. 13 and Bursa Listings Requirements allow directors to have up to 25 directorships. The number is higher in Malaysia as compared to the U.S., where a director holding less than three directorships is often considered as the best practice. “Busy directors” in the U.S. are defined as directors holding three or more directorships (see for example[3] &[4]).In a concentrated ownership environment where substantial shareholders serve as managers, the directors have to protect the interest of minority shareholders. Outside directors have an important position to monitor the management and executive directors’ actions[5]. They are expected to bring independent views into the board and add to the diversity of skills and expertise of the directors. However, findings on the effectiveness of independent directors are mostly insignificant which are not consistent with the argument of agency theory. In fact, the roles played by the executive directors and non-independent non-executive directors (gray directors) are found to be very critical in strategic activities, as in[6].It is a common feature in Malaysia that ex-government officials serve on the board of directors. From the resource dependency theory, ex-government officials may provide resources to complement the board’s expertise in terms of having specific experience and networking with government agencies. In addition, shareholdings by managers and families would be expected to act as incentives for them to maximize firm performance as their wealth is tied up to performance. Non-linear relationship is expected between executive directors’ or family directors’ ownership and firm performance as the entrenchment effect would be expected at the medium level of shareholdings and the convergence-of-interest with the outside shareholders would be expected at the lower and higher level of shareholdings.Founder is commonly associated with family controlled firm. From the agency theory perspective, having founder as the CEO (owner-manager) may reduce the agency costs[5]. As founder is responsible in initiating the business and overseeing its early growth, the way the firm is governed might be different from other managers as sustaining the firm’s growth is crucial to their descendants’ future. It is expected that CEO cum founder would enhance the firm performance. The knowledge acquired by BOD is assumed to improve the quality of actions taken. There are several reasons to expect older directors to bring better cognitive resources to decision-making tasks. Previous empirical studies have found age is associated with CEO experience, as in[7]. Reference[8] provides evidence that BOD, having experience in a particular situation or having specific expertise, would be more likely to carry out their roles in monitoring managers and to provide services and strategy. However, older directors are likely to be associated with higher commitment to status quo. The high social cohesion is expected to lead to a reluctant to challenge the status quo[9].This study attempts to examine the effects of board characteristics on firm performance. Findings of the study related to multiple directorships are expected to explain the extent of such practices by directors in Malaysia. One unique characteristic of directorship in Malaysia is the prevalence of ex-government officials serving as directors. By examining the composition of boards, further evidence on board effectiveness could be learned from an emerging market, including the effects of ex-government officials.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Multiple Directorships

- The effect of multiple directorships can be viewed from two perspectives. The first perspective, Quality Hypothesis, views multiple directorships as a proxy for high director quality[5]. Directors with multiple directorships by virtue of more networks are expected to generate benefits by helping to bring in needed resources, suppliers and customers to the company. These directors would have more experience and knowledge about industry; thus they are capable of making better strategic decisions, as in[10] and[11]. Reference[12] shows that directors with multiple directorships are effective in detecting earnings management. Another perspective, Busyness Hypothesis, assumes that directors who serve on multiple boards become so busy that they cannot monitor management adequately, which then leads to high agency costs. Accordingly, directors who serve on multiple boards would be overcommitted and as a consequence they tend to shirk their responsibilities. Several studies have suggested that having excessive multiple directorships would have negative implication on firm performance (see for example[13] and[14]). Reference[13] found multiple directorships negatively related to Tobin’s Q and positively related to ROA. The negative relationships applied to all types of directors. Likewise[4] found a negative relationship between “busy” executive directors and Tobin’s Q. A negative relationship is also found with management oversight roles and strategic roles performed by the directors as in[6]. Based on previous discussions, the following hypothesis is developed.H1: There is no relationship between multiple directorship and firm performance.

2.2. Board Size

- According to resource dependency theory, larger board size can enhance firm performance through sharing of expertise, knowledge and experience in decision making process[15]. Reference[16] and[17] propose companies should have larger board size to help improve performance. However, Reference[18] argues that agency problems exist when board size increases because of difficulties faced by the board to communicate, coordinate and make decisions. Reference[16] found a positive relationship between board size and performance as measured by return on equity (ROE) and return on capital employed (ROCE). In Malaysia, the findings are mixed. Reference[19] found a positive relationship, however[20] did not find any significant relationship with Tobin’s Q. Thus, the hypothesis tested is as follows:H2: There is no relationship between board size and firm performance.

2.3. Directors’ Age

- Age of manager can also have an effect on the selection and perspective on a strategic decision making. Further,[21] found that managerial age has a relationship with the performance of decision making and in turn will effect a company’s growth. Reference[22] concluded that older decision makers take longer time to make a decision as they need to search for more information and thus can analyze the information more precisely as compared to younger decision makers. However, older decision makers have a lack of confident in making certain decision and tend to revise their decisions if they found that those decisions will provide a negative effect to the companies.On the other hand,[23] argue that the higher age of top management that has more experienced cannot provide a guarantee that they can contribute to increase the performance of a company. They suggest that the low mental and physical energy of older managers will lead to reduced abilities in analyzing strategies thus may impinge company’s performance. Furthermore normally, younger directors are more risk taker[24]. The following hypothesis is developed to reflect the effect of director’s age on performance.H3: There is no relationship between age and firm performance.

2.4. Ex-government Officials’ Directorships

- One unique feature of the corporate scenario in Malaysia is the common practice of ex-government officials serving as directors. Ex-government officials might be appointed as directors because of their experiences and contacts in working with government agencies. By employing them, a company might find that it is going to be easier in speeding up the company’s tasks whenever the company has to deal with government agencies. Furthermore, the officials have a lot of working experience in public sector as senior officials. This experience could complement the experience of directors from private sectors. Thus, the following hypothesis is developed:H4: There is positive relationship between ex-government officials’ directorships and firm’s performance.

2.5. Founder-directors

- Founder refers to individual responsible for the firm’s early growth and development of the business[25]. Studies on the role of founder are usually related to the family controlled firms. Reference[26] developed that family values (e.g. trust and altruism) can create “an atmosphere of love for the business and a sense of commitment”. Nepotism and favoritism are held in check by the need for the family business to compete and succeed in the product and capital market. Family controlled firms are argued to pursue maximization of sales and shareholder’s value[27]. Reference[28] found a positive association between founding family controlled and firm value. Likewise,[29] found controlling shareholder and family controlled firms are associated with higher performance in Thailand. On the other hand,[30] found a negative relationship between the presence of a founding family CEO and firm value (Tobin’s Q). Based on the conflicting evidence between founders and performance, the following hypothesis is developed:H5: There is no relationship between founder and firm performance.

2.6. Executive Directors

- Executive directors play a vital role in ensuring business performance. The inclusion of executive (inside) directors on the BOD poses contradictory issues. On one hand, their inclusion is important and may lead to more effective decision-making process[5]. Executive directors can effectively assist the CEO to maximise the company’s value by providing advice and knowledge about the day-to-day operations. On the other hand, their inclusion invites scepticism as to whether they can be independent enough to judge managerial performance. Reference[31] found that the market perception on inclusion of inside directors on BOD is dependent on the level of ownership of each director. The average stock price reaction is significantly negative at low level of directors’ ownership which is less than 5%. The market infers that an inclusion of an insider as a director as an attempt to entrench existing administration. The market inferred that director ownership of between 5 to 25% would closely aligned managerial interest to that of the shareholders’ and therefore their inclusion on the board would be beneficial. Above 25% inside ownership, the announcement effect is insignificant and is not significantly different from zero. Based on the above argument it is hypothesized that:H6: There is no relationship between the proportion of executive directors on the board and firm performance.

2.7. Independent Directors

- Independent directors play an important role in monitoring management and enhancing board’s effectiveness. They are expected to bring independent views to the board and add to the diversity of skills and expertise of the directors, beside being business advisers and ‘watchdogs’, as to ensure alignment of managerial interest and firm’s value. Independent directors are important that Securities Commission makes it mandatory that at least 33 percent of the directors must be independent[32]. Empirical evidence on the relationship between independent directors and firm performance are inconclusive. Reference[33-34] found that independent directors enhance corporate governance and therefore improve firm performance, as measured by accounting and market values. Furthermore,[19] argue that independent non-executive directors are important in ensuring greater monitoring functions which lead to positive effect on firm performance as measured by value added efficiency of the firm’s physical and intellectual resources. On the contrary, several studies found that independent directors do not affect firm value[35]. Reference[36] examines the relationship between independent directors and pay-performance relationship in government-linked companies (GLCs) in Malaysia. Based on 21 selected GLCs, the study failed to detect that the percentage of independent directors on a board positively affects firm performance. Given that there is no consensus on whether the presence of independent directors improves firm performance, therefore it is hypothesized that:H7: There is no relationship between the proportion of independent directors on the board and firm performance.

2.8. Family Ownership

- Family controlled firms are expected to perform better as the family member(s) could effectively monitor the firm performance and this reduces agency problems[5]. Furthermore, family owners are bound by values of trusts and have superior knowledge about the firm’s activities as they have been in contact with the firm since its inception. On the other hand, higher shareholdings could lead family member(s) to take actions that benefit their members at the expense of firm performance. By holding substantial control rights, they could extract private benefits from the firm though excessive compensation, related party transactions, special dividends, and nonpecuniary benefits[37]. The empirical evidence on the association between performance and family ownership is mixed. Several studies found a positive association between family ownership and firm value (see for example,[38] and[39]) while[40] and[41] do not find a positive association between performance and family ownership. This study expects that similar to managerial ownership, the relationship between performance and family ownership is non-linear as at the medium level of ownership, families could entrenched themselves. Thus the following hypothesis is proposed:H8: There is a non-linear relationship between family ownership and firm performance.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection

- Population of the study is companies existed in 2008. The year 2008 is chosen as it is the year immediately after the revision of MCCG in 2007. We then excluded finance companies, PN17 companies (distressed firms), REITS, closed-end funds, and exchange traded funds. Corporate governance data are gathered from the annual reports while data on company characteristics are from Datastream. Detailed data on the directorships are gathered from the directors’ profile in annual reports. Data are then classified into different type of directors including the ex-government officials. The final sample is selected based on stratified systematic sampling. About 20% of companies are selected from each industry, resulting in a sample of 135 companies. We then excluded three companies due to non-availability of data for market-to-book value, which left the final sample of 132 companies. The sample of companies based on industry is reported in Table 1.

3.2. Data Analysis

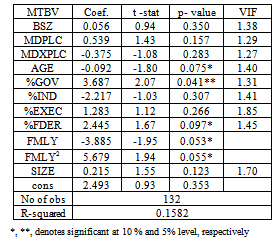

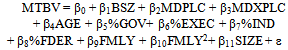

- Descriptive statistics for multiple directorships at individual level and for corporate governance at company level are analyzed. Then, regression analyses are conducted to examine the effect of corporate governance on firm performance. More specifically, the following model is estimated:

| (1) |

4. Findings and Analysis

- Table 2 summarises descriptive statistics for the sample. Based on the final sample of 132 companies, the average board size is 7.7 with a minimum of 4 members and a maximum of 15 members. Multiple directorships are determined by using three measures: MDPLC, MDXPLC and MD. The average directorship in public listed companies, MDPLC, is 1.88 with a median of 1.6. MDXPLC measures directorships in non-public listed companies. For 75 companies, the number of directorships in non-listed companies is not mentioned specifically; instead directorships are mentioned by stating that a director also serves on board of several non listed companies. Thus, this study assumes that whenever a director is mentioned to serve on several boards, it means that the director serves on five boards. Five boards are chosen since if a director is on three or less boards, then the number of non-listed companies are mentioned. The average number of MDXPLC according to this definition is 1.55 with minimum and maximum directorships are 0 and 7.11 respectively. MD measures total directorships in either public or non-public companies or it is the total of MDPLC and MDXPLC. On average, directors’ age for the sample is 56 while maximum serving age for the sample is 71. The average number of ex-government officers serving as director is 1.56 and they made up about 20% of total directors (%GOV). They are on boards of 90 companies or 68% of the sample size.

|

|

5. Conclusions

- The objective of this study is to assess the impact of board characteristics on firm performance in Malaysia. Board characteristics of interest include family ownership, fraction of government officials on the board, fraction of founder, fraction of executives, fraction of independent directors, directors’ age, board size, and multiple directorships (director’s busyness). It is found that family ownership, the presence of ex government officials, founders serving on boards and younger directors have significant influence on firm’s performance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We wish to acknowledge comments by reviewers at College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM) and we are grateful to UUM for funding this research. All remaining errors are the responsibility of the authors.

References

| [1] | Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance 2012, Securities Commision Malaysia, http://www.sc.com.my/eng/html, 2012. |

| [2] | R. M. Haniffa and Terry E. Cooke, (2002). Culture, corporate governance and disclosure in Malaysian corporations. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Abacus, 38, 3, pp. 317-349, 2002. |

| [3] | Stephen P. Ferris, Murali Jagannathan and A.C. Pritchard, Too busy to mind the business? Monitoring by directors with multiple appointments. The American Finance Association, The Journal of Finance, 53, 2, pp. 1087-1111, 2003. |

| [4] | Jayati Sarkar and Subrata Sarkar, Multiple board appointment and firm performance in emerging economies: Evidence from India, Elsevier, Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 17, pp. 271-293, 2009. |

| [5] | Eugene F. Fama, and Michael C. Jensen, Separation of ownership and control. University of Chicago Press, Journal of Law and Economics, 26, pp. 301–325, 1983. |

| [6] | Hasnah Kamardin and Hasnah Haron, Internal corporate governance and board performance in monitoring roles: evidence from Malaysia. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 9, 2, pp. 119-140, 2011. |

| [7] | Alvin Frederick Zander, Making group effective (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publisher, 1994. |

| [8] | Mason A. Carpenter and James D. Westphal, The strategic context of external network ties: examining the impact of director appointments on board involvement in strategic decision making, Academy of Management Journal, 4, No. 4, pp. 639-660, 2001. |

| [9] | Margarethe F. Wiersema and Karen A. Bantel, Top management team demography and corporate strategic change. Academy of Management Journal, 35, No.1, pp. 91-121, 1992. |

| [10] | James R. Booth and Daniel N. Deli., Factors affecting the number of outside directorships held by CEOs. Elsevier, Journal of Financial Economics, 40, 1, pp. 81-104, 1996. |

| [11] | Winfried Ruigrok, Simon I. Peck and Hansueli Keller, Board characteristics and involvement in strategic decision making: Evidence from Swiss companies. Blackwell Publishing Limited, Journal of Management Studies, 43, 3, pp. 1201-1226, 2006. |

| [12] | Norman Mohd Saleh, Takiah Mohd. Iskandar and Mohd. Mohid Rahmat, Earnings management and board characteristics: Evidence from Malaysia, National University of Malaysia, Jurnal Pengurusan, 24, pp. 77-103, 2005. |

| [13] | Roszaini Haniffa and Mohammad Hudaib, Corporate governance structure and performance of Malaysian listed companies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 33,7-8, pp. 1034-1062, 2006. |

| [14] | Beverley Jackling and Shireenjit Johl, Board structure and firm performance: Evidence from India’s top companies. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17, 4, pp. 492-509, 2009. |

| [15] | Jeffrey Pfeffer and Gerald R. Salancik, The external control of organizations: A resources dependence perspective, Stanford Business Books, Stanford, CA, 2003. |

| [16] | Olayinka Marte Uadiale, The impact of board structure on corporate financial performance in Nigeria, Canadian Centrer of Science and Education, International Journal of Business and Management, 5, 10, pp.155-166, 2010. |

| [17] | Dan R. Dalton, Catherine M. Daily, Jonathan L. Johnson, and Alan E. Ellstrand, Number of directors and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management, Academy of Management Journal, 42, 6, pp. 674-686, 1999. |

| [18] | Michael C. Jensen, The modern industrial revolution, exit and failure of internal control systems. The American Finance Association, Journal of Finance, 48, pp. 831-880, 1993. |

| [19] | Zubaidah Zainal Abidin, Nurmala Mustaffa Kamal, and Kamaruzaman Jusoff, Board Structure and Corporate Performance in Malaysia. Canadian Center of Science and Education, International Journal of Economics and Finance, 1, 1, pp. 150-164, 2009. |

| [20] | Nazli Anum Mohd. Ghazali, Ownership structure, corporate governance and corporate performance in Malaysia. Emerald Group Publishing limited, International Journal of Commerce and Management, 20, 2, pp. 109-119, 2010. |

| [21] | Michael L. McIntyre, Steven A. Murphy, Paul Mitchell, The top team: Examining board composition and firm performance, Emerald Group Publishing limited, Corporate Governance, 7, 5, pp. 547-561, 2007. |

| [22] | Ronald N. Taylor, Age and experience as determinants of managerial information processing and decision making performance. Academy of Management, Academy of Management Journal, 18, 1, pp. 74-81, 1975. |

| [23] | Koufopoulos, D., Zoumbos, V. and Argyropoulou, M. Top management team and corporate performance: a study of Greek firms. Emerald Group Publishing limited, Team Performance Management. 14, (7/8), pp. 340-363, 2008. |

| [24] | John Child, Managerial and organizational factors associated with company performance. John Wiley and Sons Inc., Journal of Management Studies, 11, pp. 13-27, 1974. |

| [25] | Belen Villalongaa and Raphael Amit, How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value, Elsevier, Journal of Financial Economics, 80, pp. 385–417, 2006. |

| [26] | Chami, R. What’s different about family business? Working Paper, University of Notre Dame, 1999. |

| [27] | Chandra S. Mishra ,Trond Randøy and Jan Inge Jenssen, The effect of Founding Family Influence on Firm Value and Corporate Governance, John Wiley and Sons Inc., Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting, 12, 3, pp. 235-259, 2001. |

| [28] | Ruth Seow Kuan Tan, Pheng Lui Chng, and Tee Ween Tan, CEO share ownership and firm value. Springer, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 18, pp. 355–371, 2001. |

| [29] | Yupana Wiwattanakantang, Controlling shareholders and corporate value: Evidence from Thailand, Elsevier, Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 9, pp. 323–362, 2001. |

| [30] | David Yermack, Higher market valuation of companies with small board of directors, Elsevier, Journal of Financial Economics, 40, pp. 185-211, 1996. |

| [31] | Shamsul-Nahar Abdullah, Board composition, CEO duality and performance among Malaysian listed companies, Emerald Group Publishing limited, Corporate Governance, 4, 4, pp. 47-61, 2004. |

| [32] | Securities Commission, Malaysian code of corporate governance. Available at http://www .sc.com.my, retrieved on November 3, 2011. |

| [33] | Gosh C. and Sirman C.F. , Board Independence, ownership structure and performance: evidence from real estate investment trust, Springer, Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 26 , 2-3, pp. 287-318, 2003. |

| [34] | Eric Lehmann and Jurgen Weigand, Does the governed corporation perform better? Governance and corporate performance in Germany, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Europe Finance Review, 4, pp. 157-195, 2000. |

| [35] | Jira Yammeesri and Siriyama Kanthi Herath. Board characteristics and corporate value: evidence from Thailand, Emerald Group Publishing limited, Corporate Governance, 10, 3, pp. 279-292, 2009. |

| [36] | Chee-Wooi, Hooi and Tee Chwee-Ming, The monitoring role of independent directors in pay-performance relationship: the case of Malaysian government link companies. ResearchGate, Macroeconomics and Finance in Emerging Market Economies, 3, 2, pp. 245-259, 2010. |

| [37] | Harry DeAngelo and Linda DeAngelo, Controlling stockholders and the disciplinary role of corporate payout policy: a study of the Times Mirror Company, Elsevier, Journal of Financial Economics, 56, 2, pp. 153–207, 2000. |

| [38] | Noor Afza Amran and Ayoib Che Ahmad, Corporate governance mechanisms and performance: Analysis of Malaysian family and non-family controlled companies, David Publishing Company, Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 6, 2, pp. 1-15, 2010. |

| [39] | Wengyi Chu, The influence of family ownership on SME performance: Evidence from public firms in Taiwan. Springer Science Business Media, LLC. Small Business Economic, 33, pp. 353–373, 2009. |

| [40] | Haslindar Ibrahim and Fazilah Abdul Samad, Agency costs, corporate governance mechanisms and performance of public listed family firms in Malaysia. Association of Professional Managers in South Africa, South Africa Journal of Business Management, 42, 3, pp. 17-25, 2011. |

| [41] | Trond Randøy, Clay Dibrell and Justin B. Craig., Founding family leadership and industry profitability. Springer Science and Business Media, LLC. , Small Business and Economics, 32, pp. 397–407, 2009. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML