-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(2): 93-98

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130302.05

Evaluating Brand Equity in Public Health Campaigns

Nottakrit Vantamay

Department of Communication Arts and Information Science, Faculty of Humanities, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, 10900, Thailand

Correspondence to: Nottakrit Vantamay , Department of Communication Arts and Information Science, Faculty of Humanities, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, 10900, Thailand.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Brand equity has become one of the key concepts used for evaluating commercial brands widely by marketing communications practitioners. However, its role for evaluating public health campaigns has rarely been established. Therefore, this study is aimed to use brand equity as a framework for evaluating public health campaigns. The three national public health campaigns in Thailand for reducing alcohol consumption among Thai youth were purposively selected in this study. They included “MAO MAI KUB” (Don’t Drive Drunk), “NGOD LAO KAO PUNSA” (No Drink in the period of Buddhist Lent Festival), and “RUBNONG PLAUD LAO” (No Drink in freshman initiation activities). The empirical results after simple regression analysis in all three campaigns showed that campaign message exposures from marketing communications tools had a significantly positive relationship with brand equity. Besides, the findings from binary logistic regression analysis in all three campaigns also indicated that brand equity affected alcohol consumption among Thai youth significantly. This study suggests that brand equity can be used as a valuable framework for evaluating the outcome of public health campaigns effectively.

Keywords: Brand Equity, Public Health Campaigns

Cite this paper: Nottakrit Vantamay , Evaluating Brand Equity in Public Health Campaigns, Management, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 93-98. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130302.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Brand equity has become an important issue for evaluating commercial brands widely among marketing communications practitioners. Brands that have high brand equity provide many benefits including positive consumer attitudes, willingness to pay premium prices, higher margins, brand extension opportunities, more powerful communication effectiveness, higher brand preferences, repeat purchases, and future profits[1-4]. However, its role for evaluating public health campaigns has rarely been established. Besides, branding in public health campaigns is a previously underutilized strategy but it is currently growing, especially in social marketing communications[5]. Therefore, evaluating brand equity in public health campaigns is very beneficial because it will help practitioners in public health and social marketers understand how campaigns are working among target audiences. The three national public health campaigns in Thailand for reducing alcohol consumption among Thai youth were purposively selected in this study because alcohol consumption among Thai youth has become a major public health concern in Thailand over the past few decades[6]. The campaigns in this study included “MAO MAI KUB” (Don’t Drive Drunk), “NGOD LAO KAO PUNSA” (No Drink in the period of Buddhist Lent Festival), and “RUBNONG PLAUD LAO” (No Drink in freshman initiation activities). Therefore, the main objectives of the current study were two fold: to investigate the causal relationships between campaign message exposures from marketing communications tools and brand equity, and to seek the causal relationships between brand equity and alcohol use behavior among Thai youth.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brand Equity Framework

- Brand equity can be defined as the value that consumers associate with a brand, as reflected in the dimensions of brand loyalty, perceived quality, brand associations, brand awareness, and other proprietary brand assets[7]. Products with high brand equity can confer positive consumer attitudes, willingness to pay premium prices, higher margins, brand extension opportunities, more powerful communication effectiveness, higher brand preferences, repeat purchases, and future profits. Consequently, brand equity has become a common way to evaluate the value of commercial brands. David A. Aaker developed a brand equity model with ten dimensions, The Brand Equity Ten[7]. The Brand Equity Ten is the ten sets of measures grouped into five dimensions. The first four dimensions represent customer perceptions of the brand – loyalty, perceived quality, associations, and awareness. The fifth is market behaviour measures that represent information obtained from market based information rather than directly from customers. His model was originally designed with traditional consumer products (e.g. cars and toothpaste) in mind. However, brand equity’s role for evaluating public health brands has rarely been established. Public health brands can be differentiated from commercial brands by only their purposes. Commercial branding is aimed to change buying behaviors but public health branding is intended to change health behaviors[8]. However, branding can also apply to both business sectors and public health sectors. In public health sectors, branding can be used in communication campaign planning to reduce health-risk behaviors among populations such as tobacco use, physical inactivity, alcohol use, and sexual-risk behaviors. After reviewing comprehensive literatures, the researcher found that, in recent years, Evans and his colleagues have adapted the Aaker’s brand equity model and used four dimensions or constructs from The Brand Equity Ten–loyalty, perceived quality, associations and awareness – to evaluate a public health brand aimed at smoking prevention in USA, The Truth campaign[8]. The fifth dimension was not used because it was not applicable for public health campaigns. Later, Price and his colleagues have also adapted the Aaker’s brand equity model by using these four dimensions to evaluate a public health brand aimed at promote physical activity among children aged 9-13 years (tweens) in USA, The VERB campaign[9]. These previous studies with both campaigns supported that campaign message exposures affected brand equity and brand equity also affected health behaviors significantly. In other words, the construct of brand equity mediate the relationship between branded health message exposures and intended behavioral outcomes. Besides, they found that each brand equity subscale – loyalty, perceived quality, associations and awareness – affected health behaviors. That is, respondents with higher brand loyalty, perceived quality, etc. were less likely to perform health-risk behaviors[8-9]. These studies suggest the potential value of using a brand equity framework to evaluate public health campaigns. However, no studies to adapt the Aaker’s brand equity framework for evaluating a public health brand aimed at alcohol use prevention among youth (15-24 years old). Consequently, Study on this topic is very beneficial because alcohol use among youth has become a major public health concern in many countries around the world. Besides, it will also help practitioners in public health and social marketers understand how alcohol prevention campaigns are working among youth. Importantly, studies about using a brand equity framework for evaluating a public health brand aimed at other health-risk behaviors are still more needed because they will help increase an understanding and extend the knowledge basis of brand management in public health more growing.

2.2. Alcohol Consumption Situations among Thai Youth and Alcohol Prevention Campaigns in Thailand

- Alcohol consumption among Thai youth has become a major public health concern in Thailand over the past few decades. National studies in Thailand have indicated a significant increase in the use of alcohol among the 15-24-year-old age group; national surveys have found that the proportion of Thai youth using alcohol increased from 21.6 % in 2001, to 23.5 % in 2004, and to 23.7 % in 2006. In addition, the latest national surveys of Thailand in 2011 reported that the proportion of Thai youth using alcohol is still at 23.7 % and beer is the most consumed alcoholic beverage among this age group. Moreover, 79.7 % of current Thai drinkers over 15 years old reported that they first tried alcohol at the age of 15-24 years old. One study indicated that 37.3 % of Thai adolescents in Bangkok were alcohol users. Among them, 42.1% were lifetime alcohol users, 56.1% were frequent drinkers (1-20 days in the preceding 30 days of the survey), and 1.7% were heavy drinkers (more than 20 days in the preceding 30 days of the survey). Beside, the percentage of drinkers among young Thai females tend to increase both in the 15-19-year-old and 20-24-year-old age groups, respectively[10]. Consequently, Thai youth should be recognized as a major risk group involved in alcohol use, particularly university students. Several studies in Thailand reported the widespread use of alcohol among Thai university students (18-24 years old). A majority (83.5 %) of public university students in Bangkok reported using alcohol, and 97.2 % of private university students in Bangkok reported trying alcohol. A recent study indicated that 53 % of university students in the west of Bangkok and Metropolitan areas were lifetime alcohol users. Furthermore, alcohol use among Thai university students was related to a wide variety of problems including drunk driving, fighting, social relationship, academic problems, health problems, and financial problems[10]. To deal with this problem, Thailand has used social marketing communication campaigns to prevent alcohol use among youth as an important intervention along with other interventions including laws, tax, and education policies. The well recognized and national alcohol prevention campaigns among youth in Thailand included three projects: “MAO MAI KUB” (Don’t Drive Drunk), “NGOD LAO KAO PUNSA” (No Drink in the period of Buddhist Lent Festival), and “RUBNONG PLAUD LAO” (No Drink in freshman initiation activities). These public health brands have been launched for almost ten years and collaboratively sponsored by health organizations in Thailand including Ministry of Public Health, Thai Health Promotion Foundation (Sor Sor Sor), Don’t Drive Drunk Foundation, The Office of the Network to Stop Alcohol Consumption (Sor Khor Lor), and other relevant groups. “MAO MAI KUB” has formally been started in 2002 and followed by “NGOD LAO KAO PUNSA” in 2003 and “RUBNONG PLAUD LAO” in 2005, respectively. These campaigns used integrated marketing communication tools such as advertising, public relations, event marketing, direct marketing, personal media, sponsorship, and even media advocacy. The results of the campaigns were evaluated continuously and it was found that they were successful in building awareness, knowledge and public recall. The number of alcohol users over the country remains steady. The publics do not drink more than they normally drink. Figures remained constant for over the past five years with about 60% of alcohol users and about 40% of alcohol non-users[11]. However, evaluating these campaigns with a brand equity framework has previously not been conducted yet. Therefore, this study will give much valuable information for both academicians and practitioners in public health and social marketers to explore the knowledge of applying brand equity in business sectors for public health sectors. Besides, it can be said that this study is now being in a pioneering stage to apply a brand equity framework for evaluating public health campaigns in Thailand.

3. Research Method

3.1. Survey Methodology

- A cross-sectional survey was undertaken from August to September 2012 in Bangkok, Thailand. The self-reporting questionnaires were collected from 400 undergraduate students in eight universities located in Bangkok Metropolitan area by multistage sampling technique (King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, Chulalongkorn University, Kasetsart University, Kasem Bundit University, Siam University, Krirk University, and Dhurakij Pundit University). The students were asked to complete the questionnaire after they were informed that their participation was voluntary, that their responses were anonymous and confidential, and that results would be reported only in a group format. All signed informed consent forms were separated from their questionnaires.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Campaign Message Exposures

- Message exposures to anti-alcohol campaign from marketing communications tools in the last 3 months were measured using a 5-point rating scale, where 1 = never, 2 = seldom (1-2 times/ month), 3 = sometimes (3-4 times/month), 4 = often (5-6 times/month), and 5 = always (7 times or more/month). The exposures scale included 15 items. The reliability analysis by Cronbach’s alpha was done in a pretest to evaluate the internal consistency of this summed scale. The results in three campaigns showed that alpha levels ranged from 0.86 to 0.93. Scores within this range are considered as an adequate indication of internal consistency of the data.

3.2.2. Brand Equity Scale

- The development of the brand equity scale and subscale was theoretically guided by the Aaker’s brand equity model with adaptations suitable for public health brands as recommended by Evans and Hastings[12]. The brand equity scale consisting of four underlying brand equity subscales – brand loyalty, perceived quality, brand associations and brand awareness – was used to assess three alcohol prevention campaigns among youth. It was measured using a 5-point Likert-type agreement scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Higher scores indicated higher brand equity. The brand equity scale included 37 totaled items. The reliability analysis by Cronbach’s alpha was also done in a pretest to evaluate the internal consistency of this summed scale. The results in three campaigns showed that alpha levels ranged from 0.82 to 0.91. Scores within this range are considered as an adequate indication of internal consistency of the data.

3.2.3. Alcohol Consumption Behavior

- To assess this variable, the dichotomous question (yes or no) was used in this part. Respondents were asked to answer the dichotomous question: In the last 3 months, did you drink alcohol? Response categories were “yes” (1) or “no” (0). This method is considered as measuring the actual behaviors recommended by past studies.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

- For statistical analyses, means, standard deviation, and percentage were used in describing characteristics of the study sample. Additionally, simple regression analysis was used in examining the causal relationship between message exposures and brand equity. While binary logistics regression analysis was used in examining the causal relationship between brand equity and alcohol consumption behavior at the 0.05 level of statistical significance.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

- The sample included 400 undergraduate students, aged 18-24-years-old in eight universities in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area. Most of them were female (52.5%). The average age was 19.97 years (S.D. = 1.49, Max. = 24, Min. = 18). The average income per month was THB 6,629.00 (S.D. = 2,949.82, Max. = 15,000, Min. = 2,000). The sample studied in the third year in the highest proportion (34.5%).

4.2. Brand Equity in Three Studied Campaigns

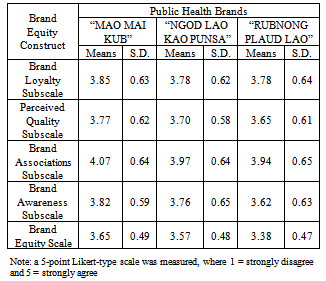

- The results found that “MAO MAI KUB” has the highest overall brand equity scores (Mean = 3.65, S.D. = 0.49) and is followed by “NGOD LAO KAO PUNSA” (Mean = 3.57, S.D. = 0.48) and “RUBNONG PLAUD LAO” (Mean = 3.38, S.D. = 0.47), respectively as shown in Table 1.

|

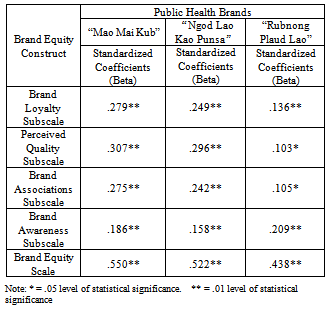

4.3. Effects of Message Exposures on Brand Equity

- After simple regression analysis had been performed, the results found that campaign message exposures from marketing communications tools positively affected brand equity scale and its four subscales in all studied campaigns. In other words, the Thai youths with higher message exposures will have higher brand equity scores. “MAO MAI KUB” showed the highest effect of message exposures on brand equity among studied campaigns (Beta = .550) and was followed by “NGOD LAO KAO PUNSA” (Beta = .522) and “RUBNONG PLAUD LAO” (Beta = .438), respectively as shown in Table 2. The results in this part support that using marketing communications tools can be used to boost overall brand equity scale and its four subscales in public health campaigns effectively.

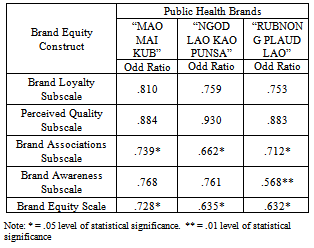

4.4. Effects of Brand Equity on Alcohol Consumption

|

|

5. Conclusions

- Brand equity performs as a mediating construct between branded campaign message exposures and alcohol consumption behavior. Higher branded campaign message exposures indicated higher brand equity. Besides, youths with higher brand equity were less likely to be alcohol users. This study showed that the brand equity construct can be used for evaluating public health brands effectively, like commercial brands. Future studies should utilize brand equity as a social marketing campaign planning, developing, managing, and evaluating tool for a sustained change in health behaviors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author wishes to thank the Department of Communication Arts and Information Science, Faculty of Humanities, and Graduate School of Kasetsart University, Thailand for financial support on presenting this research paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML