-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2013; 3(2): 89-92

doi:10.5923/j.mm.20130302.04

Local Brand Momentum through Hypermarket Channel

Hasliza Hassan 1, Muhammad Sabbir Rahman 2

1Faculty of Management, Multimedia University, Jalan Multimedia, 63100, Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia

2Graduate School of Management, Multimedia University, Jalan Multimedia, 63100, Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Hasliza Hassan , Faculty of Management, Multimedia University, Jalan Multimedia, 63100, Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

A major challenge for local entrepreneurs to compete and sustain in the market is the capability of creating brand awareness. This awareness could be boosted through brand momentum. The variety of product and service brands on the market have made the new local entrants step back while watching the main players continuously move forward. The aggressive efforts by international brands that have a huge marketing budget have managed to stifle the local competitors. In line with this, the Malaysian Government introduced the One District One Industry (Satu Daerah Satu Industri) programme to assist the local entrepreneurs by providing space in certain hypermarkets as a platform to grab the attention of new potential consumers. This research proposes a conceptual framework concerning the impact of local brand momentum through the hypermarket channel. Four main elements will be emphasized in this research: 1) local brand, 2) One District One Industry (SDSI) through hypermarkets, 3) consumer behaviour, and 4) brand momentum.

Keywords: Brand Momentum, Channel, Hypermarket

Cite this paper: Hasliza Hassan , Muhammad Sabbir Rahman , Local Brand Momentum through Hypermarket Channel, Management, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 89-92. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20130302.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In line with the effort to encourage local entrepreneurships, the Malaysian Government has launched tremendous development strategies. One of the strategies is the introduction of the One District One Industry (Satu Daerah Satu Industri) programme. Those local entrepreneurs who are participating in this programme will have the chance to market their newly established product and service brand through selected hypermarkets in Malaysia. Some of the entrepreneurs will also be qualified to market their product and service brand on the international markets through this programme if they manage to meet the basic requirements for the international market.

2. Local Brand

- Brand is something that is unique and is able to attract people towards a certain product or service. It is an intangible asset that is more powerful than the real product or service. Thus, it is much easier to sell the brand instead of selling the real product or service. Consumers might be influenced psychologically because of the brand instead of the product or service. This usually happens when the consumer is choosing between similar products from a known brand and an unknown brand. The true asset of business is based on the brand and consumer relationship. This is because two-thirds of consumer purchases are influence by brand[1]. Selling a brand resembles converting a story from information to imagination[2]. Brand provides rational needs and emotional needs through the simplification of choices[3]. Decision and purchase behaviour is dependent upon the favourability of a particular brand[4]. The main challenge in developing a brand is to make it well-known to the potential consumers. This research will look into potential ways to develop a newly established local brand momentum through the hypermarket retailing channel by participating in the One District One Industry (Satu Daerah Satu Industri) programme that was introduced by the Malaysian Government.

2.1. One District One Industry (SDSI)

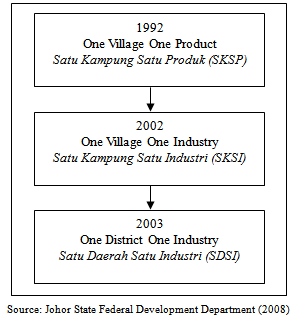

- Satu Daerah Satu Industri (SDSI), also known as One District One Industry programme, was introduced under the Sixth Malaysian Plan (RMK-6) in 1992. This programme was inspired by the One Village One Product (OVOP) programme in Japan and One Tambun One Product (OTOP) in Thailand. Initially, this programme was known as One Village One Product (Satu Kampung Satu Produk), followed by One Village One Industry (Satu Kampung Satu Industri), which was handled by the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro Based Industry, Ministry of Rural and Regional Development as well as the Malaysian Handicraft Development Corporation. Currently, this programme is assigned to the Ministry of Entrepreneur and Co-operative Development (MeCD) and is supported by various other ministries[5]. The milestones of the programme are shown in figure 1.Initially, the main focus of this programme was to produce food and agricultural based products. With the new upgraded SDSI programme, the focus has been widened to enhance overall manpower and resources. Local entrepreneurs are encouraged to participate in the programme to enhance their 1) income, 2) socio-economic stability, and 3) district capability to produce at least one or two products or services and to compete at the national and international level[5]. Through ongoing training, guidance and a maximum loan of RM50,000 with a four per cent interest rate, the programme will assist in improving the overall local entrepreneurship products and services on the market[6] in various areas such as homestay, rural industry, beauty, local craft, food and beverages[7].

| Figure 1. SDSI’s Milestone. |

2.2. Consumer Behaviour

- Although nobody totally understands consumers[9], it is important to operate a business according to consumer knowledge. However, this knowledge is concealed in the minds of the consumers[10]. Sales can be achieved through brand awareness[11]. Thus, brand awareness is important to less knowledgeable consumers[12]. In this research, an endorser is an external factor that will enhance new product awareness[13]. New local brand awareness is expected to be endorsed by hypermarkets since they are the places that many consumers go to purchase their basic household necessities.Most consumers believe that they are highly involved with grocery retailing[14]. Consumer behaviour is more unpredictable today than in previous decades since consumers tend to seek greater variety[15]. The change in consumer behaviour is due to an assortment of factors[16] and is influenced by ethics, value, economics and family structure[17]. It is impossible to treat all shoppers homogeneously, and, indeed, the same shopper might also change their behaviour depending on the situation[18]. Actual experience will provide product or service knowledge [19]. Consumers will generate basic knowledge and evaluation based on well-known brands and follow-up with less known brands[20]. The response towards new information of brands is dependent on the existing knowledge of the particular brands. The impression of a brand for those who already know it is more stable than those who are not familiar with the brand. Those who know a certain brand will only reduce their positive perception towards that particular brand if they are exposed to negative trait associations[21]. Consequently, consumers tend to purchase products and services from brands that they like and trust[22]. Consumers in developed countries are less concerned with food brands[23. 24]. On the other hand, consumers in Asia tend to go for well-known brands[25]. Parallel with this perception, it is also believed that there is high interdependence among those who are highly tolerant of incongruity and low involvement in product evaluation[26]. Eastern people are more interdependent and tolerate incongruity more than Westerners[27]. With this perception, it is expected that Eastern people, including Malaysians, accept more new product brands than Western people. Malaysians who are staying in urban areas tend to spend 1.5 times more money than those who are staying in rural areas and their expenditure is more on food, groceries and personal care items[28], which could be purchased from a hypermarket.Local consumers tend to perceive overseas brands with international or foreign spokespersons as better than local brands[4]. Further research has also proven that there is also a perception that most Malaysian consumers are highly price conscious and tend to be less choosy for fast moving consumer products[29]. Thus, it is expected that the proposed conceptual framework from this research will provide a clearer path to discover consumer behaviour towards new local brands on the Malaysian market.

2.3. Brand Momentum

- A newly established brand could be innovated to boost the brand momentum[30]. Brand momentum will enhance brand awareness to the customer through marketing. The momentum only exists in the minds of customers, and should be managed to build a competitive advantage and prevent brand dilution. The three curses of momentum are 1) increased expectation, 2) amplification and 3) over-extension. Brand momentum is not stable and can be easily influenced by many factors. However, it can be controlled 1) internally, which can be easily managed and 2) externally, which cannot be easily managed. The reaction of customers towards brand momentum is dependent on the culture of certain places[31]. In this research, the brand momentum is expected from consumer behaviour towards new local brands that are available in hypermarkets. The consumer acceptance towards the new brand could be enhanced if the brand matches the consumer’s personality[32].

3. Conceptual Framework

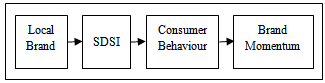

- Local brands that are introduced through the SDSI programme are expected to create consumer awareness and influence consumers to purchase the new product or service brands. If the quality of the new product and performance of the service is comparable to well-known brands, it will encourage those consumers who have tried the product to continue to purchase it. One of the ways to encourage the consumer to try the product is by giving free samples for testing in the hypermarket. A clear explanation will also motivate the consumer to purchase the product. Similarly, for service, consumers should always be encouraged to try new services while shopping at the hypermarket to enhance their experience. This will indirectly boost the local brand momentum. A conceptual framework for local brandmomentum through hypermarkets by the One District One Industry (SDSI) programme is proposed, as shown in figure 2.

| Figure 2. Local brand momentum through hypermarket channel |

4. Conclusions

- It is expected that local entrepreneurs could develop new product or service brands by participating in the SDSI programme. Awareness of this new brand could be developed through observation of consumers at hypermarket. It is expected that the consumer will accept the products and services by continuously supporting the local entrepreneurs’ brands instead of being biased towards international brands. The positive momentum can only be achieved if there is strong support from the local consumers towards the local entrepreneurs.

5. Recommendations

- Effort should always be made to identify consumers needs in shopping environments to enhance their satisfaction, repeat visits and positive word of mouth[33]. However, the shopping experience might not be the same for different shopping contexts, for example, shopping for groceries and shopping for clothing[34]. Thus, it would be more worthwhile to emphasize certain product and service categories to gain a more precise research outcome. For example, the product could be categorized under perishable and non-perishable items, with perishable products being further sub-categorized as vegetables and fruits or poultry, while non-perishable products could be sub-categorized as foods and beverages. Similarly, services could also be categorized as free services, such as parking lot, trolley and automatic price checker, as well as paid services, such as restaurant, bank and post office.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This research project has been supported by the Multimedia University, Malaysia, through an internal research grant. Special appreciation is given to the Research Management Centre of the university for approving this research project under the Mini Fund Research Cycle 1/2012 (Project ID: IP20120511014).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML