-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2012; 2(5): 251-265

doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20120205.13

Case Studies with Treatment Interventions among Ten Family Businesses in Istanbul

Ethem Tarhan

Industrial Engineering Department, Istanbul Kultur University, Istanbul, 34156, Turkey

Correspondence to: Ethem Tarhan , Industrial Engineering Department, Istanbul Kultur University, Istanbul, 34156, Turkey.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The primary purpose of this study was to present family businesses in Turkey as case studies as a way to describe the extent to which family members were aware of their family business dynamics and of any issues that interfered with their business processes. Also, the secondary purpose was to investigate the impact of two levels of a consultative relationship on awareness of family business problems in ten family businesses in Istanbul, Turkey. Moreover, the combined mixed-method research findings indicated that there were similarities between Turkish family businesses and Western family businesses as far as business family dynamics were concerned.

Keywords: Family Business, Conflict Resolution, Intensive Consultation, Brief Consultation, Communication

Cite this paper: Ethem Tarhan , "Case Studies with Treatment Interventions among Ten Family Businesses in Istanbul", Management, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 251-265. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20120205.13.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Two thirds of all enterprises worldwide are family-owned businesses (Gersick, Davis, Hampton &Landsberg, 1997),[21]. The life span of family businesses is short because only a limited number survive into the second generation. Of those that do survive into the second generation, almost one-third fail to survive into the third generation (Paisner, 1999). Those that do survive, do so because they are able to maintain effective management through effective communication between the family and the business[20].This study investigatedthe characteristics that might lead to the failure of family businesses in Istanbul, Turkey, and was based on a semi-structured interview for ten family businesses in Istanbul; developed specifically for the purposes of the study. The study investigated whether consulting could help family business members improve their communication and management skills and reduce conflicts of interest within family-owned businesses. The three main objectives were as follows. First, family businesses were investigated as case studies that described the extent to which family members were aware of their own family business dynamics and any problematic issues that were interfering with their business processes. Second, the study investigated the impact of two levels of a consultative relationship on the awareness of family business problems in ten of these businesses (volunteers) randomly assigned to the two levels of a consultative relationship. Third, the study investigated whether these ten family businesses needed to identify and address any simmering problems so that the businesses could survive their own family dynamics. To increase communication and reduce conflicts of interest within family-owned businesses, this study brought together the family business owners,other family members, and top non-family managers; gave them an opportunity to exchange their views; and let them know the vision of the company. This intervention consisted of consulting with, and educating members of the organization, both family members and top non-family managers, to establish and implement an effective training plan or road map. In all cases, the resolution of intra-business conflicts was viewed as crucial to survival.

2. Purpose

- The purpose of this mixed-method research study was to investigate if consulting will reduce conflict and improve communication with family business members. The study investigated the impact of the two levels of a consultative relationship on the awareness of family business problems in ten volunteer businesses randomly assigned to one of the two levels of a consultative relationship. These two levels of consultations were labeled as “intensive” and “brief.” The intensive consultation took approximately three hours, and the brief consultation took two hours; five companies received an intensive consultation, and the other five received a brief consultation. The study described the nature of intra-business conflicts and proposed ways to solve some of these conflicts within Turkish family businesses. The goals of this mixed-research study were as follows: (a) to help family members recall the family history of their business, (b) to help family members review their own contributions to the business, (c) to identify the most successful members in the history of the family business and the source of their success, (d) to make members aware of a common ground and their diverging perceptions in reviewing the business history and their own contribution, (e) to identify the sources of conflict in the family business, (f) to uncover “triangles” in communication, (g) to train family members to recognize triangles, and (h) to sensitize family members to the ways in which triangles reduce anxiety, but maintain conflict within the family and therefore threaten the business (Baker & Wiseman, 1998).

3. Literature Review

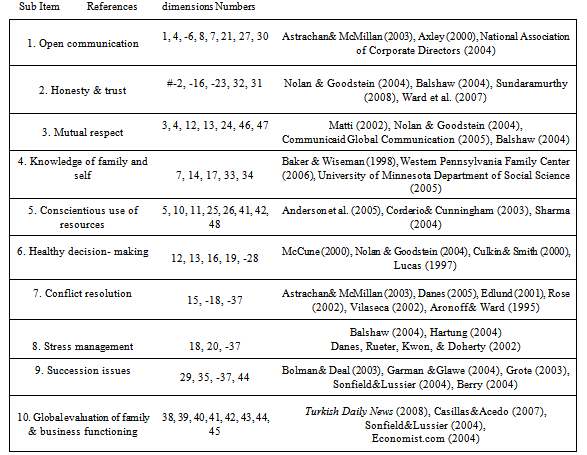

- According to Sharma (2004), who reviewed 217 refereed articles on family business, the majority of research in the past decade has been directed toward the individual or group levels, with only a minor interest in the organizational level[20]. The topics of human resource practices, cultural development, organizational vision, and inter-organizational relationships need further investigation. Moreover, the impact of family firms at the societal level has largely been ignored. Therefore, family-owned businesses should put more emphasis on these issues through the use of consulting and research in order to improve their organizational performance[20].According to Casillas and Acedo (2007), who reviewed all papers published in the Family Business Review from its foundation in 1988 through the December 2005 issue, research studies help in understanding family businesses despite the fragmentation and lack of consensus,[11]. Because family business is a relatively new field of study, the discipline is in the process of seeking its own identity. It is constantly in dialogue with other disciplines such as economics, psychology, family systems, and entrepreneurship, which makes the existing literature on the study of family-owned businesses more valuable,[11].The research and theoretical literature on family business failure identified key areas that resulted in untimely business termination. In this study, the Family Business Survey (FBS) was developed to reflect these sub-dimensions. Open communication, honesty and trust, mutual respect, knowledge of family and self, conscientious use of resources, healthy decision making, conflict resolution, stress management, global evaluation of family and business functioning, and succession issues are sub-dimensions of the FBS that were derived from the literature review of family-owned businesses in Western settings and in Turkey. Experts on family business problems argue that the greatest problem faced by family businesses is communication because very often a business owner has a vision for the future, but has not articulated it to anyone (Fleming, 1997),[22]. For communication to be effective, numerous significant phenomena play crucial roles and must be attended to on a regular basis (Bork, Jaffe, Lane, Dashew, &Heisier, 1996),[23]. Key examples include specifying and reconstructing roles as times change, restructuring the family business to accommodate role changes, being aware of the family business structure, improving the quality of the language used, and providing mutual support when facing problems. These factors not only affect communication, but can also affect and reduce conflicts of interest among family members when implemented. In family business literature, issues of trust, justice, fairness, and integrity are widely discussed as they relate to family members and non-family employees. However, psychological contracts such as individual beliefs, the acceptance of exchanges, valued payments, and perceived promises between non-family members and the family business require further research (Ward, Envick, & Langford, 2007),[24]. Socializing with family members to solve problems can be very beneficial since many issues can be handled and discussed openly among them. When family-run businesses encounter conflicts, family members can counteract this conflict by implementing several strategies (Aronoff& Ward, 1995),[2]. The strategies include the development of family policies that anticipate family business issues, initiating family conventions as a communication and conflict-resolution mechanism, putting outsiders on the board of directors, and agreeing on methods to reconcile family business conflicts. Consulting and training programs can help family members learn how to deal with conflicts of interest in family-owned businesses because conflict is normal and can be reduced if handled correctly,[3]. Personality differences, arbitrary decisions, poor perceptions, detachment among family members, and anxiety and fear are the main components of family problems that diminish success. Research has investigated the influence family members exert on the extent and frequency of substantive conflict within family firms across generations as a result of the familial relationship with the owner/manager of the firm. The positions the family members occupy in the family work group and social group are important (Davis &Harveston, 2001),[21],[17]. Conflict in a family business and the composition of the family’s work group, nonworking group, and the extensiveness of the family’s social interactions are interrelated. Differences among the generations in experience, expectations, and knowledge about the business can cause problems. Even when the next generation is responsible for the business, generational shadow variables (the degrees of influence the earlier generation still exerts) cause problems in the family business. A study of 1,000 family business owners revealed that family business problems are highly correlated with the degree of generational shadow and the dominance of the founder (Davis &Harveston, 1999),[21],[17]. One serious problem is that founding members do not have a schema for intergenerational conflict and past experiences often trigger conflict. In order to prepare for such conflicts, family business members must accept two assumptions: (1) People must admit that constructive conflict is normal and (2) there is no family relationship that does not experience some problems. Family business members must be able to respond to interfamilial conflicts guided by the influence of understanding (Gordon, 1998; Kottler, 1994),[25]. Conflict is a normal part of life, is complex, and is neither good nor bad. Individuals can learn new ways to address conflict. When people deal with conflict, the tendency is to either fight or flee (often through withdrawal from the conflict), which does not solve the conflict at all. Active listening and hearing are two effective ways of managing conflict (Danes, 2005),[16]. Perception, active listening, opencommunication commitment to growth and learning, and creative problem solving may be key factors required for family business conflict resolution. When others do recognize problems in a family business, they can adjust their view of the situation, adjust their involvement in the situation, and adjust their reaction to the situation. Danes (2005),[16] provides good recommendations for family members who try to manage conflict in family businesses and suggests that consultative relationships can be very helpful in focusing family business members on dealing with the conflict. Other research identifies that formal kin involvement in generational differences among family- owned businesses must be resolved for succession efforts to be successful. A main objective for most family businesses is to successfully run a business that outlives generations of individual family members. Consulting and training activities forintergenerational family members can be both beneficial to their business and help the global economy be more efficient and effective. However, despite the need, only limited prior research has investigated the nature of generational differences among family businesses and how consulting can help with these differences (Sonfield &Lussier, 2004),[26]. Studies have determined that first- generation family businesses do less succession planning than do second-and third-generation family firms. First- generation family-owned businesses have the highest use of equity versus debt financing (Sonfield&Lussier, 2004),[26]. Siblings who know the vision of their organization can work well together without bringing family issues to their business environment. In a recent study, Anderson, Jack, and Dodd (2005) investigated whether, to what extent, and how entrepreneurs capitalized on resources embedded in the family, especially going beyond the traditionally defined boundaries of the family firm,[1]. In a study relying on both quantitative and qualitative approaches, they reported that one quarter of the sample’s entrepreneurial network ties were kin, most of whom worked outside the family firm. However, the ties opened up a range of important resources, providing both professional and affective support. Such beneficial ties extend the family-owned business without the typical hazards of external linkages (Anderson et al., 2005),[1]. Culkin and Smith (2000) investigated how owners/managers of small firms actually think and behave. Their objective was to provide an understanding of the decision-making processes used by different types of owner/managers in the small firm sector. The authors contended that small firms should place more emphasis on what is achievable and on making sure the outcomes are entirely actionable. Similarly, Feltham, Feltham, and Barnett (2005) indicated that family businesses are often dependent on a single individual; however, little research has been conducted on this dependency,[19]. Studies have not provided an explanation for why some family businesses are highly dependent on the manager and others are not so dependent. Further research is needed to explore the power of single individuals in family-owned businesses. Consultants of family businesses are concerned with the well-being of the firm and how its members contribute to that well-being (Jaffe, 2006),[23]. The role of consultants in family businesses is not an easy task because consultants usually work in an environment where family and business relationships intersect. Moreover, bringing the whole family together in order to explore their past, present, and future as a family and in relation to their business can be difficult (Jaffe, 2006),[23]. Much research has investigated conflicts of interest and the importance of training, consulting, and communication in family-owned businesses. These studies provided some good insights regarding how to improve family businesses so that they can survive longer. The most successful family business members are the ones who can place equally powerful priorities on both their family lives and their business lives. This means that they can work with loved ones doing what they love to do (Koenig, 1999),[27]. When family matters influence the workplace, the family business can be negatively affected; for a business to be successful, everything that takes place at work needs to be professional (Koenig, 1999),[27]. Solving family business problems is crucial. Family business experts have suggested numerous ways to deal with family business problems, such as establishing a family charter and establishing two separate executive boards: one to run the affairs of the family and the other to manage the company. A recent research study of family businesses identified four fundamental governance choices that distinguish different kinds of family businesses: level and mode of family ownership, family leadership, the broader involvement of multiple family members, and the planned or actual participation of later generations (Miller & Breton, 2006),[28]. The quality of such choices seems to play an important role in why some family businesses do well over time and others do poorly. In addition, Yıldırım (2011) observed leadership styles on manufacturing family firms in Turkey. The objective of the study was to find out the relationship between owners’ transformational leadership level (TL) and entrepreneurial orientation (EO) of small and medium enterprises (SME) in Turkey using the data from the West Black Sea Region. The study concluded that there is a strong correlation between owners’ TL level and SMEs’ EO. This means that higher TL level could bring about higher EO. Since, this research study observes the concept of TL and EO SMEs in a particular region of Turkey , same study may come up with different results in different parts of the country. Consequently, future research , is needed bases on data from different parts of the country,[29]. Besides, financial data obtained from family business companiesregarding the fiscal years 2008-2010. Financial performance is one of themost important indicators for sustainability. In the literature, there are limited number of articles about family business in Turkey, especially focusing on relationshipbetween family control and financial performance. The Ozer’s article is filling this gap,[30].In summary, recent studies have indicated that misunderstandings and inadequate information exchange can increase communication problems among family members and top managers, resulting in a negative impact on the performance of family-owned businesses. The research described here focused on the critical factors influencing communication and conflicts of interest among family business members (employed and non-employed) and top managers and demonstrated how shareholder training and consulting helped to reduce differences in objectives and interests and improved communication skills among family business owners and top managers.Moreover, this study investigated communication and the use of terms during the implementation of consulting, management, leadership, and effective administration among family business members in order to look for ways to improve family businesses. The specific focus in the mixed-method research study was to explore how the shareholder training and education in the family systems approach could help to reduce conflicts and increase communication. References in the literature review supported the need for training and educational programs within family-owned businesses. As evidenced by previous studies in the literature review, many family business problems such as succession, unprofessional working habits, and lack of planning exist, but the most significant problem for family businesses is failed communication. Open communication, honesty and trust, mutual respect, knowledge of family and self, conscientious use of resources, healthy decision making, conflict resolution, stress management, global evaluation of family and business functioning, and succession issues are sub-dimensions of the FBS that were derived from the literature review of family-owned businesses in Western settings and in Turkey.

4. Method

- This study investigated whether or not consultation reduced conflict and improved communication and business functions within family businesses. The study combined mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) and experimental design with two treatment variations with an intensive case study analysis strategy to observe family business problems and address the research questions. Since this study was the first of its kind in Istanbul to describe family businesses that were open to consultation and intervention to improve family functioning, it had to focus on businesses that would volunteer. From a total of 72 candidate family-owned businesses in Istanbul, Turkey, 10 volunteered under the condition that they and their family members and non-family employees would not be identified by name. The businesses demonstrated similarcharacteristics, such as being in business for at least 25 years and employing a minimum of 30 workers. All participants and survey respondents provided informed consent before the data collection. The broad general problems for this study were conflicts of interest between family members and top managers of family-owned businesses as well as the identification of what can be done to help family businesses in Istanbul, Turkey, survive and be more successful. This study investigated characteristics that might lead to the premature failure of family businesses.The hypotheses and research questions were postulated to test relationships between variables in alignment with the requirements of quantitative and qualitative research approaches (Kumar, 2007). The study addressed the following research questions: 1. Research question 1 asked for a description of the domains in which this sample of volunteering businesses in Istanbul experienced weaknesses or strengths from a family dynamics perspective.2. Research question 2 asked what the impact was on volunteering family businesses in Istanbul, Turkey, of intensive consultation versus brief consultation.The study has the following directional hypotheses:1. If consultation is effective, the FBS scores for participants in the intensive consultation condition will be higher than those in the brief consultation when subsequent scores are controlled for their original scores.2. Participants in the intensive consultation condition will be more likely to want additional consultations, as measured by the Consultation Request Form (CRF).This study tests the following null hypotheses:1. The null hypothesis is that the consultation will have no effect. Identical FBS scores are received in the intensive consultation condition as in the brief consultation condition.2. The null hypothesis is that there will be no difference in the request for additional consultation between the intensive and brief consultation conditions. A primary purpose of this study was to describe the dynamics and problematic issues faced by ten family businesses in Istanbul, Turkey. Since this topic has not previously been investigated in Istanbul, which is a unique megacity (more than 15 million residents) in a trading region with business and family traditions going back for thousands of years, the first purpose was to collect descriptive data on the nature of the family business dynamics in these volunteer businesses. Four separate information collection strategies were used. First, the study relied on a newly drafted quantitative survey written in Turkish (the FBS) containing 48 Likert-type items to identify the key issues faced by family businesses. The items were written and selected based on the literature on family businesses in Western settings. The FBS investigated whether or not similar issues are present in these ten Istanbul businesses. As the second method for data collection, qualitative focus group interviews were used with five randomly selected family businesses to investigate whether different, previously unidentified issues could be uncovered, as well as whether the relative frequency and importance of different issues and problems were different from those in Western settings. The third source of information was the CRF used at the end of the study to gather information from family business members about the sub-dimensions of family business strengths and weaknesses for which they would see the benefit from a consultation. The fourth and final source of information was the notes that the consultant took during the observations and interactions with the businesses as a natural part of the consultation processes along with anydocumentation available to the consultant about the businesses.

4.1. Information Collection Methods: The Family Business Survey (FBS)

- The FBS consists of 48 Likert-type items on a 6-point, “strongly agree”–to–“strongly disagree” scale as described in Appendix A. The items were developed and written in Turkish specifically for this study to reflect the major sources of family business strengths and weaknesses. The FBS was based on ten factors (sub-dimensions) that were identified as leading to a family business collapse and termination or to business strength, as summarized in the Review of the Literature. The choice of the Likert-type, quantitative scales was based on their long tradition as a reliable and valid methodology to use when scholarship has identified internally valid constructs and sub-constructs that support specific uses (Braun, 2002; Fields, 2002). Since the research and theoretical literature on family business failure has identified key areas that can result in untimely business termination, the FBS was developed to reflect these sub-dimensions.

4.2. Rationale for the Proposed Design

- The combined mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) and experimental design with two treatment variations with an intensive case study analysis strategy (Yin, 2008) allowed the findings to address the research questions most effectively and efficiently. First of all, the large number of responses to the first and the final administrations of the survey to all members of the ten businesses allowed for two snapshots of the needs and issues in these volunteer family businesses in Istanbul, Turkey. While they were not representative of all family businesses in Istanbul as they were volunteers, they did provide some insight into the possible domain of family businesses in an important mega city that had not yet been investigated. Second, by comparing the first administration to the final administration of the FBS in the brief intervention and the intensive intervention, the effectiveness of the intensive intervention compared to the brief intervention in raising awareness and clarifying problems and solutions could be investigated. This comparison allowed for predictions to guide future research and practice with family businesses in Turkey. Third, comparing the responses to the “Consultation Request Form” in the brief versus the intensive consultation allowed for conclusions regarding the awareness of family business problems and effects of the differing levels of consultation on perceived needs, solutions, and efficacy of consultations. Some of the conclusions would most likely not be entirely certain based on this one instrument, but would most likely point in the direction of the need for additional study. Lastly, the focus group interviews when transcribed and analyzed provided additional in-depth information in participants’ own words about their perceptions of the needs, problems, and dynamics in their own businesses. Participating members’ spoken words and comments helped to elaborate on the FBS and provided an opportunity for Istanbul family business members to identify and elaborate on factors that may or may not have been mentioned in previous published research.In short, this mixed method design, with case study reporting strategies, was the optimum choice for this study because it was not only grounded in existing scholarship, but also allowed room for new factors and new emphases to emerge from participating Istanbul business people in the intensive consultation group. In addition, the combination of instruments allowed for comparisons of the impact of the brief versus intensive consultation. The integration of the focus group interviews allowed for additional data collection and at the same time facilitated and created a transition into the Intensive Consultation.

4.3. Appropriateness of the Research Design

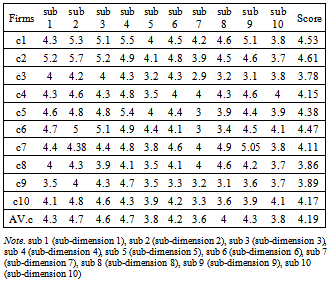

- The ten family businesses in the sample of volunteer businesses in Istanbul, Turkey, are described more fully in the following section on Sampling. The first step in the research design, once the family businesses had volunteered and expressed commitment, was to collect quantitative survey data using the FBS (see Appendix A) for as many members of the ten businesses as possible. A survey was distributed after a consent page was signed by the participant. The consent page contained the following information: “By signing this form I acknowledge that I understand the nature of the study. The potential risks to me as a participant, and the means by which my identity will be kept confidential. My signature on this form also indicates that I am 18 years old or older and that I give my permission to voluntarily serve as a participant in the study described.” All family members who are staff or stakeholders in the businesses were given a copy of the survey and a self-addressed envelope in which to return anonymously to the researcher. Family business members were asked to return the survey within two weeks of receiving it. As many as five follow-up phone calls, cards, personal visits, or emails prompted business members to complete this task. Businesses whose members completed a minimum of ten surveys by the deadline (one month following the distribution of the FBS) were allowed to stay in the study and receive the no-cost consultation. Some items were worded as strengths (“In our family business, we value each other’s opinions.”). Other items were worded as weaknesses that can cause a business to collapse (“In our family business, members do not trust each other.”). Table 1 listed the major sub-dimensions in the instrument and selected scholarly support from the literature review for each sub-dimension. Because of the complexity of business and family relationships, some items reflected more than one sub-dimension. All 48 items were connected to each related sub-dimension in Table 1. Prior to scoring the FBS, all items that reflected negative traits or weaknesses in family businesses were reverse-scored (subtracted from 7). Then all selected values for the items were summed, and the sum was then divided by 48 to yield an average scale score of 1 to 6. (Omitted items were not included in the average and the denominator was changed accordingly.) Businesses with scores near a value of “1” were considered to be lower functioning with a greater likelihood of failure, while businesses with average scores closer to “6” were considered high functioning and more likely to have immediate- and long-term success. Since individual business members fill out the survey, the score for each business was the arithmetic average of all individual surveys for the business. Once at least ten surveys had been collected from the businesses, they were scored as described previously to yield an average summed score from 1 to 6. Then the ten businesses were rank-ordered into matched pairs, and one member of the pair was assigned to the intensive (three-hour) consultation and another member was assigned to a brief (short 20-minute presentation with a pre-survey and an opportunity to ask questions) consultation. The assignment to the intensive consultation versus the brief consultation investigated the value of the consultation in helping the family businesses diagnose their problems, identify solutions, put in place action plans, and seek additional consultation. The assignment to the intensive versus the brief consultation took place as follows. After at least ten members of each business completed and returned the FBS, the average survey scores determined ranks from lowest to highest. The pretest ranking determined five pairs of businesses. For example, Rank 1 and Rank 2 formed one pair, Rank 3 and Rank 4 formed another pair, and so on. According to the randomization, the creation of “matched” intensive consultation and brief consultation groups were as follows: Ranks 1, 4, 5, 8, and 10 comprised of the Intensive Consultation Group and Ranks 2, 3, 6, 7, and 9 comprised of the Brief Consultation Group. The actual businesses falling into these two groups depended entirely on the scores on the FBS for the members returning their surveys.

|

|

4.4. Information Collection Methods: The Consultation Request Form (CRF)

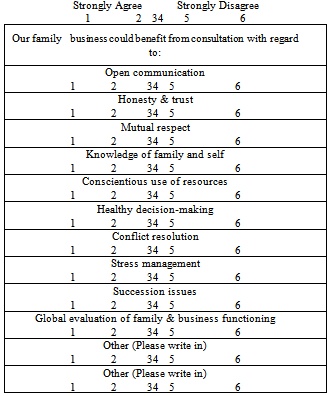

- The CRF (Table 4) asks family business members to rate which of the ten specific sub-dimensions (from the literature review) are areas in which they believe the family business could benefit from a consultation. Benefiting from a consultation required the belief that the need was there and that the conditions were such that the consultation would provide some benefits. . It was not an indicator of business strength or weakness, but rather reflected combinations of factors, including the awareness of business needs and problem areas, optimism about the impact of a consultation, and optimism regarding the ability of the company to grow and succeed. It was designed to be sensitive to the intensity of the consultation experience. The participants engaged in the intensive consultation experience were expected to request more future consultations than those not engaged in the intensive consultation.

|

5. Analysis and Results

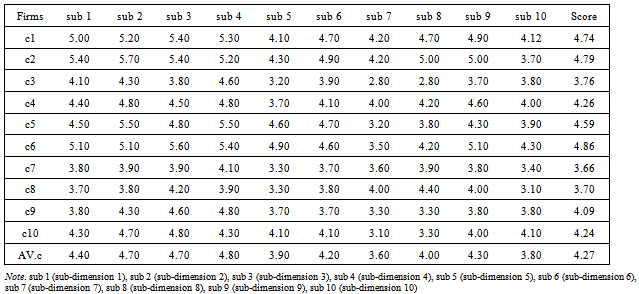

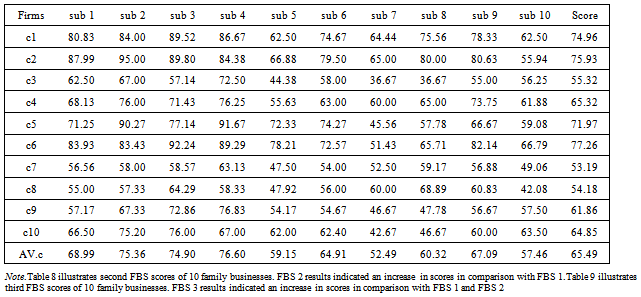

- The results of the intensive consultation group indicated that there was a 13% increase between the FBS 1 and FBS 3 scores. The average CFR score were 60.10, which meant that the family businesses in the intensive consultation group requested additional consultations in order to resolve their family business issues. Moreover, the weakest sub-dimension in the intensive consultation group was sub-7, “Conflict Resolution.” The scores of sub-7 in FBS 3 increased by 8% compared to the FBS 1. In conclusion, the intensive consultation was beneficial to family-owned businesses because the overall scores of the FBS 3 increased compared to the FBS 1 and FBS 2. The brief consultation group results are based on companies 1, 4, 6, 7, and 8. The results of the brief consultation indicated that there was a 14% increase between the FBS 1 and FBS 3 scores. The average score of the CRF was 70.02, which meant that family businesses in the brief consultation group requested additional consultations in order to resolve their family business issues. Moreover, the weakest sub-dimension in the brief consultation group was sub-5, “Conscientious Use of Resources.” The scores of sub-5 in the FBS 3 increased by 17.59% compared to the FBS 1. In conclusion, the brief consultation was beneficial to family-owned businesses because the overall scores of the FBS 3 increased compared to the FBS 1 and FBS 2. The scores of the FBS 2 and FBS 3 increased both in the intensive and brief consultation groups, which indicated the positive influence of such consultations. In addition, this study was exploratory and suggestive, and the qualitative data collections were consistent with each other.In this mixed-method research study, according to the research findings the null hypothesis was in effect because similar FBS scores were received in the intensive consultation condition as were in the brief consultation condition (see Figure 1). The directional hypotheses were tentative because it was not yet known whether the subjects would go through a stage of the problems in their family businesses more deeply as a result of the interventions before they experience positive change and improvement.

| Figure 1. Effects of brief and intensive consultations |

|

|

5.1. Methodological Analyses

- The rationale for this approach to internal validity is well grounded in instrument development literature (Linn, 2000). When a set of constructs are extracted and used to construct an assessment instrument (Braun et al., 2002; Kane, 2007)[10],[29], the next step is to investigate the diverging and converging item characteristics with regard to the identified constructs. Therefore, an exploratory factor analysis would be appropriate for this study. However, the number of total surveys was somewhat limited for a factor analysis of a 48 item survey. Because of the risk of unstable results, a factor analysis was postponed for future research.

6. Example for a Case Study with Treatment Interventions

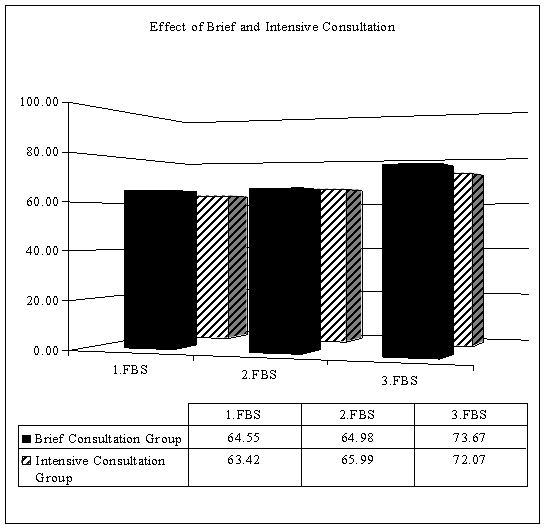

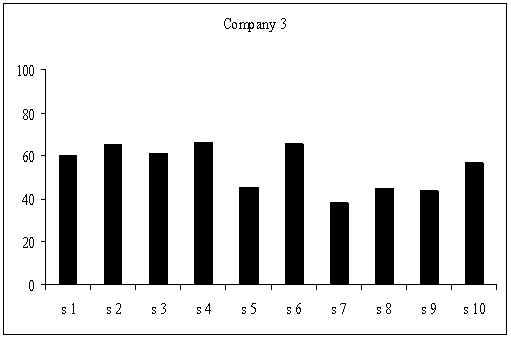

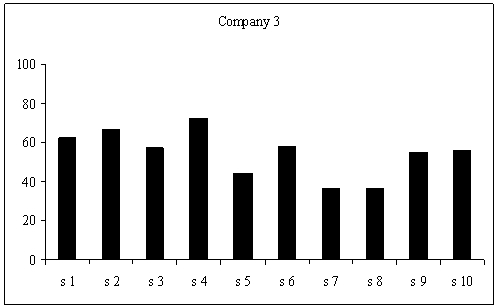

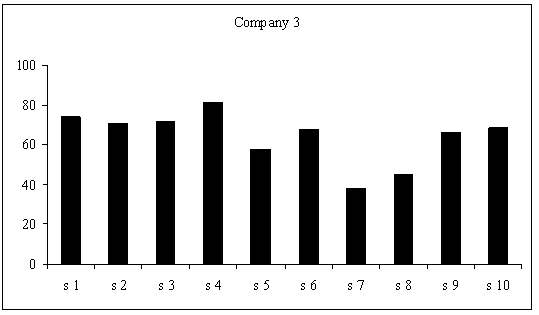

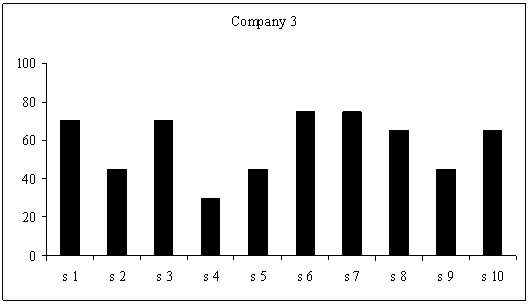

- 1) Company 3Company 3 is a typical family business with a combination of first- and second-generation family business members. This company has been in the tourism sector since 1963 as a small hotel on the Marmarian Sea coast of Turkey in a city called Erdek. Three sisters work during the summer season with their parents. There were four participants in the FBS 1, 2, 3, and in the intensive consultation. Moreover, four family business members filled in the CRF. Company 3 had the lowest FBS 1 scores, which put the company in the last rank among other family businesses. As stated in Table 7 for Company 3, the first weakest sub-dimension was sub-7 “Conflict Resolution” the second weakest sub-dimension was sub-9 “Succession Issues” and the third weakest sub-dimension was sub-8 “Stress Management.” The consultant did not give any information about the weakest sub-dimensions scores of the FBS 1 to family business members during the intensive consultation. However, these sub-dimension scores assisted the consultant during the family focus group interviews, especially in the brain storming session in the intensive consultation. The Intensive Consultation lasted approximately three hours. After participants completed the FBS a second time the consultant submitted the Family Business Focus Group Interview Guide to family business members. The purpose of the focus group interview was described by the consultant to the participants. Moreover, the consultant told the subjects to think about the past, present and future of their family business and lead into the discussion for the intensive consultation. The family business members decided to discuss effective communication, including succession issues. The participants brainstormed about issues and needs with regard to a selected theme. During the brainstorming session the consultant took notes about the events and discussions in order to help the family members to complete their action plan for the following four weeks. According to the observations of the consultant during the intensive consultation, the three sisters were willing to improve their communication skills and willing to solve their succession issues. However, during the brainstorming session it was noted that the father, who was the founder of the company, was experiencing some communication problems with his three daughters because he was talking most of the time and was not listening to the other family members. Therefore, the consultant decided to give equal time for all of the family business members in order to discuss the theme during the family focus group interviews. In this company there was a succession problem because nobody knew who would run the company in the second generation when the father retired. The consultant asked some questions about this succession issue to the family members such as who would like to volunteer to run the business and how? Figure 2, indicates Company 3, and the FBS 1 results for each sub-dimension.As illustrated in Table 6, the FBS 1 results, sub-dimension 7 “Conflict Resolution” had a score of 38.30, sub-dimension 9 “Succession Issues” had a score of 43.70 and sub-dimension 8 “Stress Management” had a score of 45.00. The FBS 2 results summarize the average scores of the ten sub-dimensions (see Figure 3).As illustrated in Table 8, the FBS 2 results, sub-dimension 7 “Conflict Resolution” had a score of 36.60 sub-dimension 9 “Succession Issues” had a score of 55.00 and sub-dimension 8 “Stress Management” had a score of 36.60. It is noted that the overall scores of the ten sub-dimensions in the FBS 2 had decreased compared to the FBS 1. After four weeks of the intensive consultation, the consultant went to Company 3 and submitted the FBS 3 for the last time. The FBS 3 results summarize the average scores of the ten sub-dimensions (see Figure 4).As illustrated in Table 9, the FBS 3 results, sub-dimension 7 “Conflict Resolution” had a score of 38.30, sub-dimension 9 “Succession Issues” had a score of 66.20 and sub-dimension 8 “Stress Management” had a score of 45.00. It is noted that the overall scores of the ten sub-dimensions in the FBS 3 had increased compared to the FBS 1 and FBS 2. In addition to the FBS 3, family business members were asked to fill in the Consultation Request Form (CRF) for the first time (see Figure 5).

| Figure 2. FBS 1 results of Company 3 |

| Figure 3. FBS 2 results of Company 3 |

| Figure 4. FBS 3 results of Company 3 |

| Figure 5. CRF score results of Company 3 |

|

|

|

7. Conclusions

- In conclusion, each of the family businesses that were surveyed has a unique culture and its own ambience and environment particular to that business. Their self-ratings on the FBS are based on their individual standards and perspectives. As a result, a business that rates itself low on using its resources might objectively be using resources in a more productive manner than a business that rates itself higher. This is not a weakness of the study, but rather a natural outcome of self-assessment and can lead to further discussion. Because two thirds of all enterprises worldwide are family businesses and the life span of family businesses is short, with a limited number surviving into the second generation and even fewer reaching the third generation, consulting with, and educating members of family businesses are of utmost importance to increase communication and reduce conflicts of interest, allowing family-owned businesses to survive longer and become more successful.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank to Istanbul Kultur University’s lecturers for their helpful suggestions, and critical and constructive comments on an earlier version of the paper.

Appendix A: Family Business Survey Example

- Family Business SurveyDirections: Please rate the extent to which the following statements are true for your family-owned business, using the scales below. Circle the number on the scale that best reflects your agreement or disagreement with the item as it pertains to your family business.Strongly StronglyDisagreeAgree1234561. Members in our family business are outspoken about issues and problems.Strongly StronglyDisagreeAgree123456Comments: 2. Shareholders in our family business don’tbring family issues to the business.Strongly StronglyDisagreeAgree123456Directions: For each of the following 10 topics, please indicate whether you agree or disagree that consultation on that topic is needed. Please respond by circling the number on the scale that best represents your level of agreement or disagreement with the statement that your family business could benefit. After you have finished selecting numbers for the scales, write comments about any of the specific items to clarify your ratings.

References

| [1] | Anderson, A. R., Jack, S. L., Dodd, S. D., “The role of family members in entrepreneurial networks: Beyond the boundaries of the family firm.”, Family Business Review, vol.18, pp.135-155, 2006. |

| [2] | Aronoff, C., & Ward, J., “Run the business like a business (conflict resolution: Family Business: Planning)”. Nation’s Business, vol.83, no.49, pp.51, 2006. |

| [3] | Astrachan, J. H., & McMillan, K. S., Conflict and communication in the family business. Marietta, GA: Family Enterprise, 2003. |

| [4] | Online Available:http://solutions.iienet.org/imissues/800axley.pdf |

| [5] | Online Available: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com |

| [6] | Online Available:http://www.mediationworks.com/mti/certconf/bib-fambiz.htm |

| [7] | Online Available:http://www.mediationworks.com/mti/certconf/bib-fambiz.htm |

| [8] | Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E., Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and Leadership, 3rd ed., San Francisco: Jossey-Bass., 2003. |

| [9] | Online Available:http://www.mediationworks.com/mti.index.html |

| [10] | Braun, H. I., The role of constructs in psychological and educational measurement, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2002. |

| [11] | Casillas, J., &Acedo, F., Evolution of the intellectual structure of family business literature: A bibliometric study of FBR. Family Business Review, vol.20,pp.141, 2008. |

| [12] | Online Available:www.communicaid.com/turkey-business-culture.aspCorderio, P. A., & Cunningham, W. G., Educational leadership: A problem-based approach, 2nd ed, New York: Allyn& Bacon, 2003. |

| [13] | Culkin, N., & Smith, D., “An emotional business: A guide to understanding the motivations of small business decision takers”, Qualitative Market Research, vol.3, no.3, pp.145, 2004. |

| [14] | Online Available:http://sdanes.cehd.umn.edu/managingconflict/ |

| [15] | Danes, S. M., Rueter, M. A., Kwon, H. K., Doherty, W., „Family FIRO model: An application to family business”, Family Business Review, vol.15, pp.31-43, 2002. |

| [16] | Davis, P. S., &Harveston, P. D., The phenomenon of substantive conflict in the family firm: A cross-generational study. Retrieved June 11, 2006. |

| [17] | Online Available:http://www.csupomona.edu/~uwc/non_protect/student/3ways.htm |

| [18] | Feltham, T, S., Feltham, G., Barnett, J. J., ”The dependence of family businesses on a single decision-maker”, Journal of Small Business Management, vol.43, pp.15, 2006. |

| [19] | Sharma, P.,“An overview of the field of family business studies: Current status and directions for the future”, Family Business Review, vol.17, no.1, 2004. |

| [20] | Gersick, K., Davis, J., Hampton, M., Lansberg, I.,„Generation to generation: Life cycles of the family business”, Boston: Harvard Business School Press,1997. |

| [21] | Fleming, P. D. ,“Helping business owners prepare for the future. Journal of Accountancy”, vol.46, no.5, pp.183, (2006). |

| [22] | Jaffe, D., “The world of family business consulting. Consulting to Management”, vol.17, no.21, 2008. |

| [23] | Ward, S. G., Erivick, B. R., Langford, M. , “On the theory of psychological contracts in family firms”, The Entrepreneurial Executive, vol.12, pp.14-37, 2008. |

| [24] | Gordon, B.,“Beyond blame: A new way of resolving conflicts in relationships”, Family Business Review: Journal of the Family Firm Institute, vol.11, no.1, pp.84-86, 2006. |

| [25] | Lussier, R. N., Sonfield, C. M., “Family business management activities, styles and characteristics: A correlation study”, Mid-American Study of Business, vol.19, no.47, 2004. |

| [26] | Koenig, N. N., “You can’t fire me I’m your father”, Franklin, TN: Hillsboro Press,1999. |

| [27] | Miller, D., Breton, I. L., “Family governance and firm performance: Agency, stewardship, and capabilities“, Family Business Review, vol.19, no.1, pp.73, 2008. |

| [28] | Kane, M. T., “Validation. In R. L. Brennan (Ed.), Educational measurement, 4th Ed, 17-64, Westport, CT: Praeger. |

| [29] | Yildirim, H., Saygin, S.,“Effects of Owners’ Leadership Style on Manufacturing Family Firms’ Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Emerging Economies: An Emprical Investigation in Turkey”, IFERA Lancaster 2010, 10th Annual World Family Business Research Conference,and European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, vol.32, pp.1450, 2011. |

| [30] | Ozer, S., H.,“The Role of Family Control on Financial Performance ofFamily Business in Gebze”,International Review of Management and Marketing,Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 75-82, 2012. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML