-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Management

p-ISSN: 2162-9374 e-ISSN: 2162-8416

2012; 2(4): 106-112

doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20120204.04

Perceptions of Organizational Downsizing and Job Satisfaction Among Survivors in Nigerian Banks

Darius Ngutor Ikyanyon

Department of Business Management, Benue State University, Makurdi, 970001, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Darius Ngutor Ikyanyon , Department of Business Management, Benue State University, Makurdi, 970001, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of the study was to determine how survivors’ perception of downsizing as financially effective, inevitable, and liberating for victims affect their job satisfaction. Data was collected from 150 survivors in 8 banks operating in Makurdi metropolis. Pearson product moment correlation coefficient and regression were tools of data analysis. The study revealed that survivors’ perception of downsizing as financially effective and inevitable negatively affect their job satisfaction. Though the relationship between survivors’ perception of downsizing as liberating for victims and job satisfaction was positive, it was not statistically significant. The analysis of variance showed that there was no difference in survivors’ perception of downsizing among the banks studied, while their level of job satisfaction varied. On the whole, we conclude that downsizing negatively affects the job satisfaction of survivors.

Keywords: Downsizing, Job Satisfaction, Survivors, Banks, Nigeria

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Maintaining the right size of workforce is central to the survival of every organization. Employees remain the most important resources of an organization and are key to gaining competitive advantage. There is therefore the need for employees to be managed effectively if an organization is to survive[1]. As a result of changes taking place within the business environment, occasioned by globalization,competition is not only tough but fierce[2]. To compete effectively, organizations need to maximize productivity, increase effectiveness and improve efficiency, which entails cost reduction as well[3]. Since organizations find themselves operating in more complex, unpredictable, and dynamic environments, they employ different strategies to achieve their goals, with downsizing one of the favoured strategies [4].“Organizational downsizing is an organization’s conscious use of permanent personnel reductions in an attempt to improve its efficiency and/or effectiveness”[5, p. 70]. This implies that downsizing is deliberate and undertaken by organizations to reduce its workforce[5-8]. Secondly, organizations that downsize are concerned with improving organizational efficiency and/or effectiveness [9-11]. However, some research evidence[12-17] suggests that most downsizing initiatives have not been as effective in achieving organizational effectiveness and/or efficiency as originally expected.Employees who are unaffected by downsizing and remain with the organization subsequent to downsizing are knownas survivors[18-19]. Since downsizing affects work processes wittingly or unwittingly[20], survivors have to adjust to the new forms of organization. Their ability to cope with the changes in the organization and perform effectively determines the success of downsizing[21-22]. It has been observed that survivors confront difficult situations like work overload, which causes fatigue and ultimately leads to dissatisfaction[3].Job satisfaction has received serious attention in organizational behaviour research due to its potential benefits to individuals and organizations. For instance, it has been reported that employees who are satisfied are productive[23-24], committed to the cause of the organization[25-30] and less likely to exhibit negative work-related attitudes which are costly to the organization such as intention to quit, turnover and absenteeism[31-32]. Research on survivors’ work-related attitudes however show that survivors exhibit a plethora of negative attitudes and behaviours such as intent to quit, decline in organizational commitment, loyalty and trust, feelings of job insecurity, and job dissatisfaction[33-34],[12],[35-36].Banks in Nigeria have embarked on massive downsizing in recent times, with a view to ensuring more efficient management to enable them deliver better returns to stakeholders[37]. There is therefore the need to examine the effect of downsizing on job satisfaction of survivors in Nigerian banks. However, most of the previous studies on survivors’ work- related attitudes, forexample[38],[34],[39-45] were carried out in Western societies. It is therefore important to enhance our understanding of organizational downsizing and job satisfaction of survivors in a non-western country. The objective of this study therefore, was to examine how survivors’ perception of downsizing affects their job satisfaction in Nigerian banks.

2. Literature Review

- Downsizing constitutes a particular form of organizational restructuring[46]; it involves the reduction in personnel[6] and frequently results in work redesign[20] in order to improve organizational productivity[47], efficiency, and effectiveness[11]. Downsizing has been used to avoid bankruptcy and secure survival[48] and is commonly adopted by firms after making large investments in labour saving technologies. Banks in Nigeria have invested in technologies as could be seen in the proliferation of ATMs and internet banking. This is perhaps one of the reasons for massive downsizing in the sector since technology has replaced most human jobs. Reference[37] found that downsizing has improved the efficiency and profitability of banks in Nigeria.Previous studies[49],[4],[14-15],[50] have shown that downsizing is not a guarantee of organizational success. Organizations that downsize still perform poorly. One of the reasons for the poor performance of organizations that downsize is that too often, the focus is on employees who are released while those that remain are neglected. The thinking is that employees who remain with the organization are relieved for not loosing their jobs. These survivors exhibit symptoms such as low morale, low productivity, increased levels of absenteeism, tardiness, cynicism, turnover, dissatisfaction, among other negative attitudes[41].The negative attitudes employees exhibit subsequent to downsizing is described as survival syndrome or sickness[38],[51]. This survival syndrome is defined as the mixed bag of behaviours and emotions often exhibited by employees following organizational downsizing[52]. Organizations have often under-estimated the negative effects of downsizing and do not consider the difficulties in motivating survivors to achieve greater productivity which is paramount to organizational success and employee job satisfaction[53].Survival syndrome is expressed in increasing anxiety and risk aversion[54-55]. Issues relating to survival syndrome can be painful and far reaching at both the individual and organizational levels. Employees often rationally understand and defend the need for downsizing but find it difficult to accept it emotionally. It is therefore important to recognize employees’ career needs and educate them on the new organizational vision and structure, while helping them process their feelings[56]. The feelings and concerns experienced by survivors are; lower morale; guilt and fear[57-58], lack of trust[40], job insecurity; unfairness; depression, anxiety, fatigue; reduced risk taking and motivation; distrust and betrayal; lack of reciprocalcommitment; dissatisfaction with planning and communication; dissatisfaction with the layoff process; lack of strategic direction; lack of management credibility; short-term profit orientation; and a sense of permanent change[43]. As a result of changes in work processes, survivors experience some pressure from work and as a result are dissatisfied following organizational downsizing[3]. This suggests that downsizing causes dissatisfaction rather than job satisfaction since survival syndrome constitutes a mixed bag of antecedents of job dissatisfaction.

3. Framework for the Study

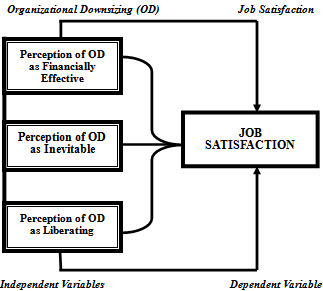

- The manner in which downsizing is implemented determines the success of the strategy in achieving organizational effectiveness. This is because employees’ perception of downsizing influences their work-related attitudes following organizational downsizing[59]. The authors suggest that the criteria used in selecting employees for downsizing must not only be clear and appropriate, but must also be perceived by all employees to be clear, appropriate, and fair. This is especially true of surviving employees as, according to[60], survivors are in a unique position to judge the fairness of downsizing and that they respond positively to this perception by becoming more committed to the organization. Survivors are not only concerned about the outcome of downsizing but the rationale for downsizing and how it was done. In this study, we consider three ways employees perceive downsizing since perception affects their attitudes after downsizing[45]. Employees may perceive organizational downsizing as being financially effective, inevitable, and liberating for victims[45]. These affect their work-related attitudes such as job satisfaction.

| Figure 1. Framework for the Study |

4. Methodology

- This study adopted the survey research design since data was collected from the participants without imposing any condition or treatment on them. A structured questionnaire was distributed to 180 layoff survivors in 8 banks operating in Makurdi metropolis namely, Union Bank, United Bank for Africa (UBA); First City Monument Bank (FCMB); Eco Bank; Access Bank; Fidelity Bank; First Bank; and Mainstreet Bank. A total of 150 questionnaires (83.33%) were duly completed and returned. The study sought to determine how survivors perceptions of organizational downsizing affects their job satisfaction. Downsizing was measured using a scale adapted from[45]. The scale has sub-scales measuring survivors’ perceptions of downsizing as financially effective; inevitable; and liberating for victims. This was measured on a 5 point Likert Scale anchored from 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”. The reliability of the scale was 0.680. Job satisfaction was measured using the job satisfaction index (JSI). This scale has been used with success among Nigerian samples. The scale measured job satisfaction on a 5 point Likert scale anchored from 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “ Strongly Agree”. The reliability of the scales was 0.579.Downsizing was considered the independent variable while job satisfaction was considered the dependent variable. Pearson’s correlation and Regression analysis were the statistical tools used to determine the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

5. Results and Discussion

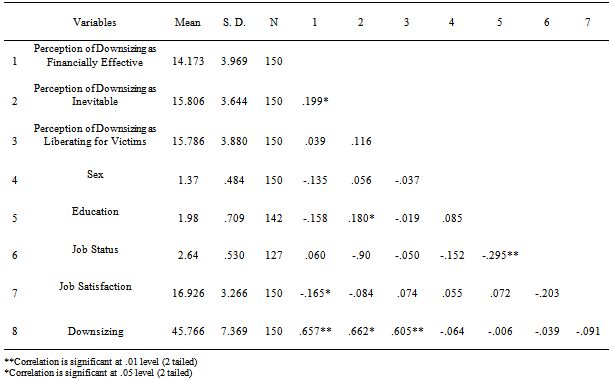

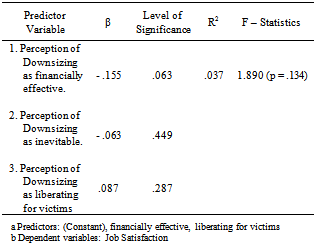

- Data analysis was based on 150 questionnaires that were duly completed and returned. The demographiccharacteristics of the respondents shows that 95 (63.3%) were male while 55 (36.7%) were female. Majority of the respondents (47.3%) were Degree holders, working at low level management (56%). The means, standard deviations and correlations between the variables of the study is presented in table 1. The correlations in table 1 indicate that survivors’ perception of downsizing as financially effective negatively correlates with job satisfaction (r = - .165, p < .05). There was also a negative correlation ( r = - .84) between survivors’ perception of downsizing as inevitable and job satisfaction. Furthermore, the table shows that though the relationship between survivors’ perception of downsizing as liberating for victims and job satisfaction was positive ( r = .074), the relationship was not significant (p > .05).

|

|

6. Conclusions

- We conclude that survivors’ perception of downsizing as financially effective and inevitable negatively affect their job satisfaction. Although the relationship between survivors’ perception of downsizing as liberating for victims and job satisfaction was positive, it was not statistically significant. This means though that survivors are concerned about those who leave the organization as a result of downsizing, this is not enough to improve their job satisfaction. On the whole, downsizing negatively affects the job satisfaction of survivors. Organizations need to adopt strategies to improve the job satisfaction of survivors since the success of downsizing rests on the shoulders of survivors who must provide both the core competencies and corporate memory necessary for moving forward into a new era of business prosperity. For suggestions on how organizations can cushion the negative effects of downsizing on survivors, see references [61], [6], [38] and[37].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I appreciate the efforts of Terna Uza, Sena Ingbian, Sandra Aondowase, Patrick Apaa and Kizito Ikyanyon in facilitating data collection. Special thanks to Tersoo Apaa for his assistance in data analysis as well as Ephraim Agber for formatting this work.

References

| [1] | Mullins, L. J. (2002). Management and Organizational Behaviour. (6th Ed.) New York: Prentice Hall. |

| [2] | George, M. J. & Jones, G. R. (2002). Organizational behaviour, 3rd Edition, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. |

| [3] | Malik, M. I., Ahmad, A. & Hussain, S. (2010). How Downsizing affects the Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction of Layoff Survivors. African Journal of Business Management, 4(16), 3564-3570. |

| [4] | Luthans, B. C. & Sommer, S. M. (1999). The impact of downsizing on workplace attitudes. Group & Organizational Management, 24(1), 46 – 70. |

| [5] | Budros, A. (1999). A Conceptual framework for analyzing why organizations downsize. Organization Science, 10, 69 – 82. |

| [6] | Cameron, K. S. (1994). Strategies for Successful Organizational Downsizing. Human Resource Management, 33(2) 189 – 211. |

| [7] | Freeman, S. J. & Cameron, K. S. (1994). Organizational Downsizing as Convergence or Reorientation: Implication for Human Resource Management. Human Resource Management, 33(2), 213 – 238. |

| [8] | Mishra, A. K. & Mishra, K. E. (1994). The Role of Mutual Trust in Effective Downsizing Strategies. Human Resource Management, 33(2), 261 – 279. |

| [9] | Bahrami, H. (1992). The Emerging Flexible Organization: Perspective from Silicon Valley. California Management Review, 34 (Summer), 33-52. |

| [10] | De Meuse, K. P, Vanderheiden P. A. & Bergman, T. J. (1994). Announced Layoffs: Their Effects on Corporate Financial Performance. Human Resource Management, 33(4) 509 – 530. |

| [11] | Kozlowski, S. J., Chao, G. T. Smith, F. M. & Hedlung, J. (1993). Organizational Downsizing: Strategies, Interventions and Research Implications. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson, (Eds.) International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. New York : Wiley. |

| [12] | Cascio, W. F. (1993). Downsizing: what do we know? What have we learned. Academy of Management Executive, 7(1), 95 – 104. |

| [13] | Lewin, J. E. & Johnston, W. J. (2000). The Impact of Downsizing and Restructuring on Organisational Competitiveness. Competitiveness Review, January. |

| [14] | Macky, K. (2004). Organizational Downsizing and Redundancies: The New Zealand Workers Experience. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 29 (2) 63 – 87. |

| [15] | Madrick, J. (1995). Corporate Surveys, Can’t Find a Productivity Revolution, Either. Challenge, 38 (Nov/Dec) 31 – 44. |

| [16] | McLellan, K. & Marcolin, B. (1994) Information Technology Outsourcing. Business Quarterly, 59 (Autumn) 95 – 104. |

| [17] | Sutton, R. & D’Aunno, T. (1989). Decreasing Organizational Size: Untangling the Effects of People and Money. Academy of Management Review, 14 (2) 194 -212. |

| [18] | Guiniven, J. E. (2001). The Lessons of Survivor Literature in Communicating Decisions to Downsize. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 15 (1), 53 – 71. |

| [19] | Virick M, Lilly, J. D. and Casper, W. J. (2007). Doing More with Less: An Analysis of Work Life Balance among Layoff Survivors. Career Development International, 12 (5), 463 – 480. |

| [20] | Richtner, A. & Ahlstrom, P. (2006). Organizational Downsizing and Innovation. SSE/EFI Working Paper Series in Business Administration, 1, 1-22. |

| [21] | Mishra, A. K. & Spreitzer, G. M. (1998). Explaining how survivors respond to downsizing: the roles of trust, empowerment, justice work redesign. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 567 – 88. |

| [22] | Mone, M. A. (1997). How we got along after the Downsizing: Post – downsizing Trust as a Double-edged Sword. Public Administration Quarterly, 21, 309 – 339. |

| [23] | Judge, T. A., Thoresen C. J., Bono, J .E. & Patton, G. K. (2001). The Job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative an quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 376-407. |

| [24] | Steinhaus, C. S. & Perry, J. L. (1996). Organizational commitment: Does sector matter? Public Productivity and Management Review 19, 278-288. |

| [25] | Al-Hussami, M. (2008). A study of nurses’ job satisfaction: The relationship to organizational commitment, perceived organizational support, transactional leadership, and level of education. European Journal of Scientific Research, 22(2), 286-295. |

| [26] | Mannheim, B. Baruch, Y. and Tal, J. (1997). Alternative models for antecedents and outcomes of work centrally and job satisfaction of high-tech personnel. Human Relations, 50(2), 1537-1562. |

| [27] | Brown, S. P. and Peterson, R. A. (1993). Antecedents and consequences of salesperson job satisfaction: Meta-analysis and assessment of causal effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 30 (1), 63-77. |

| [28] | Samad, S. (2011). The effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment and job performance relationship: A case study of managers in manufacturing companies. European Journal of Social Sciences, 18 (4), 602-611. |

| [29] | Tella, A., Ayeni, C. O., & Popoola, S. O. (2007). Work motivation, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment of library personnel in academic and research libraries in Oyo state, Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice, April, 1-16. |

| [30] | Warsi, S., Fatima, N. and Sahibzada, S. A. (2009). Study on relationship between organizational commitment and its determinants among private sector employees of Pakistan. International Review of Business Research Papers, 5(3), 399-410. |

| [31] | Jamal, M. (1997). Job Stress, Satisfaction and Mental Health: An Empirical Examination of Self Employed and Non-self Employed Canadians. Journal of Small Business Management, 35(4), 48-57. |

| [32] | Tett, R. P. & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, Turnover Intention, and Turnover: Path Analyses based on Meta-Analytic Findings. Personnel Psychology, 46(2), 259-293. |

| [33] | Armstrong-Stassen, M. (1998). Downsizing the Federal Government: A Longitudinal Study of Managers’ Reactions. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 15(4), 310-321. |

| [34] | Brockner, J. (1998). The effects of work layoffs on survivors: Research, Theory and Practice. In Staw, B. M. and Cummings, L. L. (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behaviour. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. |

| [35] | Lee, J. & Corbett, J. M. (2006). The Impact of Downsizing on Employees’ Affective Commitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(3), 176-199. |

| [36] | Ryan, L. & Macky, K. (1988). Downsizing Organizations: Uses, Outcomes and Strategies. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 36, 29-45. |

| [37] | Ikyanyon, D. N. (2011). The Impact of Downsizing on Competitiveness of Banks in Nigeria: A Study of Selected Banks in Makurdi Metropolis. International Journal of Business and Management Tomorrow, 1(3), 6-11. |

| [38] | Appelbaum, S. H., Delage, C., Labib, N. & Gault, G. (1997). The Survivor Syndrome: Aftermath of Downsizing. Career Development International, 2(6), 278-286. |

| [39] | Brockner, J. Spretizer, G. Mishra, A., Hochwarter, W., Pepper, L., & Weinberg, J. (2004) . Perceived Control as an Antidote to the Negative Effects of Layoffs on Survivors, Organizational Commitment and Job Performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 76 – 100. |

| [40] | Devine, K., Reay, T., Stainton, L. & Collins-Nakai, R. (2003). Downsizing Outcomes: Better a Victim than a Survivor. Human Resource Management, 42(2), 109 – 124. |

| [41] | Isabella, L. A. (1989). Downsizing: Survivors’ assessments. Business Horizons, 35 – 41. |

| [42] | Leana, C. R. & Feldman, D. C. (1988). Individual Responses to Job Loss: Perceptions, Reactions and Coping Behaviours. Journal of Management, 14 (3) 375 – 389. |

| [43] | Noer, D. (1993). Healing the Wounds: Overcoming the Trauma of Layoffs and Revitalizing Downsized Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. |

| [44] | Rust, K. G., McKinley, W.,& Edwards, J. C. (2005). Perceived Breach of Contract for one’s own Layoff vs. Someone else’s Layoff: Personal pink slips hurt more. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 11 (3), 72 – 83. |

| [45] | Sronce, R. & McKinley, W. (2006). Perceptions of Organizational Downsizing. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 12(4), 89-108. |

| [46] | Carbery, R. & Garavan, T. N. (2005). Organizational Downsizing and Restructuring: Issues Relating to Learning, Training and Employability of Survivors. Journal of European Industrial Training, 29 (6), 488 – 522. |

| [47] | Gandolfi, F. (2006). Corporate Downsizing Demystified: a Scholarly Analysis of a Business Phenomena. Hyderabad: ICFAI University Press. |

| [48] | Fisher, S. R. & White, M. A. (2000). Downsizing in a Learning Organization: Are There Hidden Costs? Academy of Management Review, 25 (1) 244 – 251. |

| [49] | De Vries, M. F. & Balazs, K. (1997). The Downside of Downsizing. Human Relations, 50 (1), 11 – 40. |

| [50] | Mentzer, M. S. (1996). Corporate Downsizing and Profitability in Canada. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 13, 237 – 250. |

| [51] | Littler, C. R. (1998) Downsizing Organizations: the Dilemmas of Change. Human Resources Management Bulletin, CCH Australia Limited, Sydney. |

| [52] | Doherty, N. & Horsted, J. (1995). Helping survivors to stay on board. People Management, 1(1) 26 – 31. |

| [53] | Markowich, M. (1994) Lifeboat Strategies for Corporate Renewal. Management Review, 89(9), 59 – 61 . |

| [54] | Cameron, K. S. Freeman, S. J. and Mishra, A. K. (1991). Best practice in white – collar downsizing managing contradictions. Academy of Management Executive, 5(3) 57 – 73. |

| [55] | Hui, C. & Lee, C. (2000). Moderating effects of organization-based self-esteem on organizational uncertainty: employee response relationships, Journal of Management, 26(2), 215 – 32. |

| [56] | Ndlovu, N. & Parumasur, S. B. (2005). The Perceived Impact of Downsizing and Organizational Transformation on Survivors. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31(2), 14-21. |

| [57] | Thornhill, A., Saunders, N. K. and Stead, J. (1997). Downsizing, Delayering – But where’s the Commitment? Personnel Review, 26 (2), 81 – 98. |

| [58] | Tomasko, R. (1990). Downsizing: Reshaping the Corporation of the Future. New York: AMACOM. |

| [59] | Schweiger, D. M. Ivancevich, J. M. & Power, F. R. (1987). Executive Actions for Managing Human Resources before and after Acquisition. Academy of Management Executive, 1 (2) 127 – 138. |

| [60] | Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational Justice: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, Journal of Management, 16 (2) 399-432. |

| [61] | Samaha, H. E. (1993). Helping survivors stay on track. Human Resource Professional, 5(4), 12-14. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML