-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Modern International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics

2017; 1(1): 1-4

doi:10.5923/j.mijpam.20170101.01

The Monty Hall Show and Murphy’s Score

Marcia R. Pinheiro

IICSE University, USA

Correspondence to: Marcia R. Pinheiro, IICSE University, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In 2000, Doctor Priest gave a talk at the Newcastle University where he claimed that perhaps something was wrong with Combinatorics, since The Monty Hall Show proved to us that the mathematicians’ reasoning there failed. We watched his talk with our very eyes. The argument is that the statistics of the show would serve as evidence to the claim. Basically, the winning strategy seemed to be switching doors or changing the initial choice after one of the doors had been opened. As we know, mathematicians (what means us) would say that the chances of winning are the same regardless of the strategy adopted by the subject if the set of strategies resumes to switching or sticking. In 2008, Doctor Baumann published a paper in Synthese where he supported Priest’s 2000 claims regarding this problem. We here intend to prove ALSO to the philosophers, group where we should ALSO be included, that our mathematical principles in terms of Combinatorics and this problem could not be any sounder than they are. We will do this by means of exposing the fallacies in their reasoning. In this paper, we make use of analytical tools. Through delicate analysis of the arguments against our thesis, we are able to isolate problematic points. We then allow the reader to compare their proposal, after due fixing, with their original proposal in order to have them agreeing with our points.

Keywords: Monty Hall, Paradox, Logic, TV, Combinatorics

Cite this paper: Marcia R. Pinheiro, The Monty Hall Show and Murphy’s Score, Modern International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, Vol. 1 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-4. doi: 10.5923/j.mijpam.20170101.01.

1. Introduction

- Doctor Graham Priest (St. Andrews, 2002) gave a talk at the Newcastle University (Newcastle, 2016) in 2000 during which he stated that the Monty Hall Problem (The New York, 2008) was a problem worth studying because it defied the laws of Mathematics.Whoever was there heard: The words might not have been exactly these, but the intentions were.Well, all that we know about this problem is that it appears to be connected to a TV show where a car would be hidden behind a door. The other doors would have something else behind them. The person participating in the game would choose one of the three doors and if they guessed right, like if they chose the door that had the car behind it, they would get the car. The presenter would open one of the two doors that remained (not chosen) after the person made the first choice. That door would never have the car.It is then said that they have studied the problem from the TV show and if the person changed their choice at that stage, like after the revelation of the contents of one of the two remaining doors, then the person would have more chances of getting the car because it was by studying the history of the show that they reached that conclusion, like, statistically, that would be the case.More recently, Doctor Peter Baumann came up with (Baumann, 2008), his article appeared in Synthese, and some of the most relevant extracts are:

What is the Monty Hall Problem? It is based on a TV game show (Let´s Make a Deal!) which was popular in the US some decades ago. Here is the basic outline. The player is confronted with three closed doors. Behind one door is a prize he wants but there is nothing he would want behind the other two doors. The player can pick one door and keep what is behind it. Unfortunately, the player does not know which door is the winning door. After the player has picked one door, the host, Monty Hall (MH), opens another door with nothing of interest behind it. The player then has the choice between making his initial choice his final one and getting what is behind the chosen door plus $100 (sticking) or switching to the other, remaining door, getting what is behind it but no additional $100. All this is common knowledge between the player and the host. What would a rational player who is interested in the best possible outcome for himself do – stick or switch?

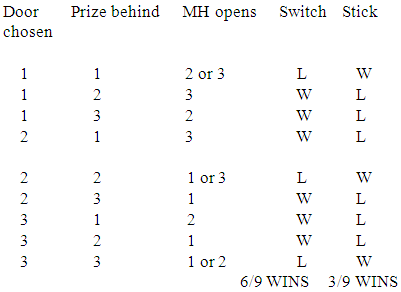

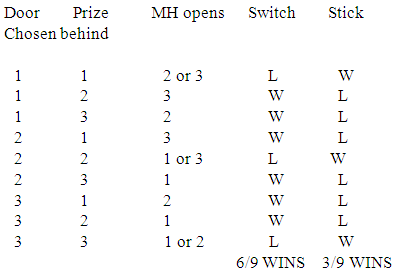

What is the Monty Hall Problem? It is based on a TV game show (Let´s Make a Deal!) which was popular in the US some decades ago. Here is the basic outline. The player is confronted with three closed doors. Behind one door is a prize he wants but there is nothing he would want behind the other two doors. The player can pick one door and keep what is behind it. Unfortunately, the player does not know which door is the winning door. After the player has picked one door, the host, Monty Hall (MH), opens another door with nothing of interest behind it. The player then has the choice between making his initial choice his final one and getting what is behind the chosen door plus $100 (sticking) or switching to the other, remaining door, getting what is behind it but no additional $100. All this is common knowledge between the player and the host. What would a rational player who is interested in the best possible outcome for himself do – stick or switch? The intuitive answer for most people is Stick. It is based on the idea that the probability that the prize is behind the originally chosen door equals the probability that it is behind the remaining door (1/2 in both cases). However, one can show relatively easily that this intuition is mistaken. The player can originally choose between three doors and the prize can be behind any of these three doors. This gives us nine equally probable scenarios which are both mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive. Let numbers stand for the different doors and W and L for winning and losing respectively:

The intuitive answer for most people is Stick. It is based on the idea that the probability that the prize is behind the originally chosen door equals the probability that it is behind the remaining door (1/2 in both cases). However, one can show relatively easily that this intuition is mistaken. The player can originally choose between three doors and the prize can be behind any of these three doors. This gives us nine equally probable scenarios which are both mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive. Let numbers stand for the different doors and W and L for winning and losing respectively: Sticking only gives one a 1/3 chance of winning whereas switching gives one a 2/3 chance of winning. Hence, the rational player will switch. Application of Bayes´ Principle leads to the same result but is less intuitive.In this paper, we will exhibit the fallacy contained in the extracts of Doctor Baumann’s article and the fallacy contained in Doctor Priest’s talk.

Sticking only gives one a 1/3 chance of winning whereas switching gives one a 2/3 chance of winning. Hence, the rational player will switch. Application of Bayes´ Principle leads to the same result but is less intuitive.In this paper, we will exhibit the fallacy contained in the extracts of Doctor Baumann’s article and the fallacy contained in Doctor Priest’s talk. 2. Development

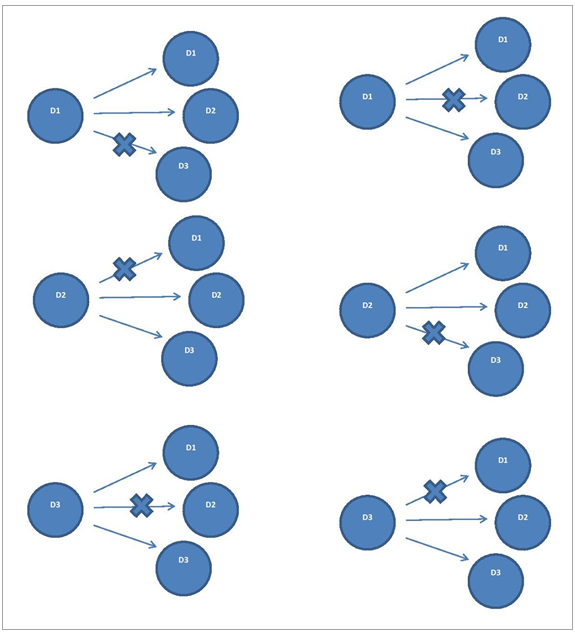

- First we address Doctor Priest’s talk (2000).Please notice that we have three choices available the first time the question is asked and therefore one chance in three of finding the car (about 33% or 1/3). One of the doors is open and no car appears. We are now left with two doors. One of them has the car. Has the probability changed? Yes, sure! Now we have 50% or 1/2 of chance of getting the car, like it is more likely that we get it, since one door has been eliminated from the game and did not contain it.What happens if we change our choice? We then have 50% of chance again, is it not?Notice that the first choice will never have any effect on the second because the presenter always opens a door without a car behind it, and he surely is not allowed to swap the car in-between the first and the second choice of the subject (even though we would like to claim that that is precisely what the staff does, and that is why we get those results). Notice that the door is not closed again and mixed, as we do with the cards game and we have not eliminated the possibility of getting a non-car by opening that door. If we considered those to be two sets of doors, and we had to get car in both to win, then we could think of conditional probability, right? If we chose the car on the first choice, 1/3, and the car on the second choice, 1/2, then we would have a probability of 1/3 x 1/2 of getting it, that is, of 1/6 or approximately 16.67%.The way the problem is, however, we have about 33% of chance with the first choice. If we change the choice after the door is open, then we have 50% of chance of getting it, and if we stick to the same door, we also have 50% of chance of getting it. Why is it that the history of choices of the show seems to conflict with this conclusion then? As in Brazil, with Silvio Santos, more than likely (same sort of game), we can only assume that people would change doors more rarely (as we see written on Extract 2), and it was then the choice of the production to swap the position of the car so that the person would lose, like that is just a TV show… . We are then given three doors, so let’s call those D1, D2, and D3. We have a first choice, before one of them is revealed, and that will always be a door that does not contain the car and is not our choice that far, and a second choice, which happens after the revelation, basically. If we were to draw a permutation tree for this problem, it would look like this:

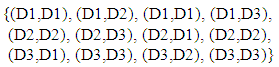

Basically, the first balls are the choice of the contestant on the first time and after that choice they will be presented with three doors again, but one will be eliminated, which is the one that appears with the cross.With that, we have the following couples of results as our possibilities set:

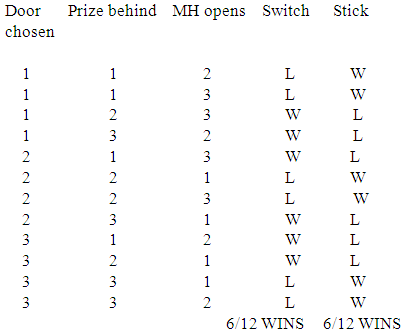

Basically, the first balls are the choice of the contestant on the first time and after that choice they will be presented with three doors again, but one will be eliminated, which is the one that appears with the cross.With that, we have the following couples of results as our possibilities set: The cardinality of this set is 12. Notice that in six of the possibilities there is equality between the first and the second choice, what then gives 50% of the results as possible. If we swap, that is, if the second choice or the second member of the couple changes, then we have the other 50%. We have then proven that the chances are 50% for those who stick to the same door and 50% for those who change on the second opportunity.We think that this settles the possible problem with the Mathematics involved.Were the game honest, we probably should notice some similarity of wins between the people who swap and those who stick. Notice however that luck is luck and some numbers get out of the globe/bag more times than others with draws controlled by auditors in the popular games we have, say the game Lotto in Brazil. If we could draw a rule that were deterministic, this would be purely mathematical, not also statistical (probability falls to the side of Statistics). Whatever is statistical is not supposed to be deterministic by nature, so that the results are not predictable in terms of real life. The best we get is a percentage in terms of chances of getting it right.Also, if we could predict results, then we would always win, what would obviously make profit impossible to the side of the organization running the game.We now address the issues with Doctor Baumann’s theories.For that, we go straight to the table he presented to us:

The cardinality of this set is 12. Notice that in six of the possibilities there is equality between the first and the second choice, what then gives 50% of the results as possible. If we swap, that is, if the second choice or the second member of the couple changes, then we have the other 50%. We have then proven that the chances are 50% for those who stick to the same door and 50% for those who change on the second opportunity.We think that this settles the possible problem with the Mathematics involved.Were the game honest, we probably should notice some similarity of wins between the people who swap and those who stick. Notice however that luck is luck and some numbers get out of the globe/bag more times than others with draws controlled by auditors in the popular games we have, say the game Lotto in Brazil. If we could draw a rule that were deterministic, this would be purely mathematical, not also statistical (probability falls to the side of Statistics). Whatever is statistical is not supposed to be deterministic by nature, so that the results are not predictable in terms of real life. The best we get is a percentage in terms of chances of getting it right.Also, if we could predict results, then we would always win, what would obviously make profit impossible to the side of the organization running the game.We now address the issues with Doctor Baumann’s theories.For that, we go straight to the table he presented to us: The main issue is that every unit counts in probability, and we are not counting a few with this reasoning. Look at the fixed table:

The main issue is that every unit counts in probability, and we are not counting a few with this reasoning. Look at the fixed table: Doctor Baumann is apparently a computer scientist (Jacobs, 2009). It does not really matter what his exact background is, since we usually reason in the way what we lecture leads us to. That means that he wants to optimize the presentation of things, but he may forget to look at the details, and those are all that matters for mathematicians: Things like counting two different factors as two instead of one.The interesting thing is that Doctor Baumann answers his own question in quite an obvious way when he writes the following paragraph:There is no doubt that with respect to a large enough sample of Monty Hall games the player should switch. But what if we look at a single game (cf. Moser and Mulder 1994 and Horgan 1995)? I want to argue that we run into serious problems if we apply probabilistic notions and arguments like the one above to a single Monty Hall game. The application of such notions and arguments to a single case (a single game) does not make sense; hence, there is no answer to the question what the rational player should do in an isolated case, at least no probabilistic answer. My argument involves a variation of the original scenario for two players.Oh, so if we had only one round, Mathematics would be correct. Is that right?Guess what happens between one round and another: Dishonest Mathematics or dishonest show?Oh, oh, if you give the wrong answer now we have the rights to play the horn on your ear!Notwithstanding, Doctor Baumann had not yet seen our paper, so that he chose the first option: Dishonest mathematicians (oh, oh, oh: That is our class!). He then managed to find a way to change a single round into a dishonest thing too, that is, into something that looks as if the mathematicians keep on telling lies to everyone else for ages. See:

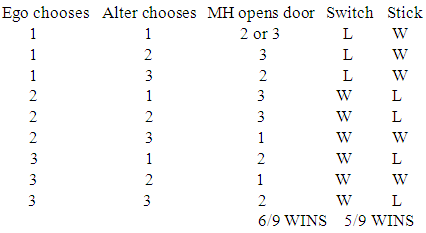

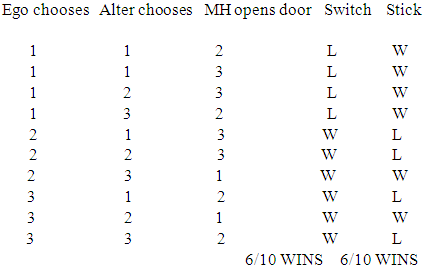

Doctor Baumann is apparently a computer scientist (Jacobs, 2009). It does not really matter what his exact background is, since we usually reason in the way what we lecture leads us to. That means that he wants to optimize the presentation of things, but he may forget to look at the details, and those are all that matters for mathematicians: Things like counting two different factors as two instead of one.The interesting thing is that Doctor Baumann answers his own question in quite an obvious way when he writes the following paragraph:There is no doubt that with respect to a large enough sample of Monty Hall games the player should switch. But what if we look at a single game (cf. Moser and Mulder 1994 and Horgan 1995)? I want to argue that we run into serious problems if we apply probabilistic notions and arguments like the one above to a single Monty Hall game. The application of such notions and arguments to a single case (a single game) does not make sense; hence, there is no answer to the question what the rational player should do in an isolated case, at least no probabilistic answer. My argument involves a variation of the original scenario for two players.Oh, so if we had only one round, Mathematics would be correct. Is that right?Guess what happens between one round and another: Dishonest Mathematics or dishonest show?Oh, oh, if you give the wrong answer now we have the rights to play the horn on your ear!Notwithstanding, Doctor Baumann had not yet seen our paper, so that he chose the first option: Dishonest mathematicians (oh, oh, oh: That is our class!). He then managed to find a way to change a single round into a dishonest thing too, that is, into something that looks as if the mathematicians keep on telling lies to everyone else for ages. See: Once more, and now we all know, we just have to count two as two and it is all what it should be. See:

Once more, and now we all know, we just have to count two as two and it is all what it should be. See:

3. Conclusions

- Thanks to Doctor Baumann, we finally know where people got their questioning from, like what sort of reasoning has made them question the mathematical foundations. This part of Combinatorics has been around for ages, and it has been extensively tested in practice. It would be very unlikely that they had found a genuine fault with this part of the discipline. Notwithstanding, we did find Doctor Priest’s talk amusing in that 2000, so that we felt like saying a word here.We conclude the expected: Those who stated that there should be some problem with this piece of Combinatorics were the ones who had clear fallacies in their arguments. Doctor Baumann forgets the importance of a unit in Mathematics. Maybe, for the sake of presenting things to others, the Computer Scientist can appeal to a less detailed table, but a mathematician, if attempting to prove a result in Combinatorics using what we call Permutation Tree, would not be allowed to skip the details involved, not even one line. What Doctor Baumann did was presenting two units as if they were one. That is cheating in the World of Mathematics, and it looks pretty bad. We must go through each result individually when we build a tree, precisely because it is easy to commit a mistake. Since his results in the paper we here criticize are all based on the tables we here present, we decided not to talk about anything else apart from those. In proving those are equivocated, all that follows in his paper would contain fallacies. The Monty Hall Problem is an allurement to show us how cynical human kind can be: It is obviously the case that economical interest, and not fairness, moves the show organizers to put the car in another door in the middle of the game. The same thing must have happened in Brazil, in a show ran by Silvio Santos, the owner of SBT. The show was almost exactly the same thing. Notwithstanding, we don’t recall having seen scientific studies about that show. The reason must be that Brazilians are used to be lied to, especially by those from the top, and they then are always with what is there called a foot behind. The entire Country would think that it is probably the case that they did something dodge, not that the mathematical foundations should be put into questioning.On the other hand, the English people, for example, seem to use sarcasm to refer to obvious crime, so that it is possible that all that was meant by all the people who studied this problem was that either the so solid foundations of Mathematics are equivocated or there is realistically something really weird going on there.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML