-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Microbiology Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5885 e-ISSN: 2166-5931

2015; 5(5): 149-156

doi:10.5923/j.microbiology.20150505.02

Camel Brucellosis: Its Public Health and Economic Impact in Pastoralists, Mehoni District, Southeastern Tigray, Ethiopia

Habtamu T. T.1, Richard B.2, Dana H.3, Kassaw A. T.1

1Mekelle University, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mekelle, Ethiopia

2Colorado State University, Department of Biomedical Science, Fort Collins, USA

3Colorado State University, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Fort Collins, USA

Correspondence to: Habtamu T. T., Mekelle University, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mekelle, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Camel brucellosis is a disease caused by Brucella mellitensis and B. abortus with considerable public health and economic importance to as owners consume raw milk. A cross-sectional study was conducted from May 2014 to April 2015 with the objective of identifying risk factors associated with infection of pastoralists and estimating their economic losses due to camel brucellosis in Mehoni District, Northeastern Ethiopia. From a total of 415 camel sera collected from three peasant associations, 24 camels were found positive by Rose Bengal plate test (RBPT), and 14 of them were confirmed by complement fixation test (CFT). The overall sero-prevalence of Brucella antibodies in camels was 5.80% (24) and 3.37% (14) by RBPT and CFT, respectively. From a total of 120 camel owners participated in the interview, about 91% (109) drank fresh raw milk regularly, and 11.01% (12) of them owned the sero-positive camels. The risk of Brucella infection was found to be high (88.33%, 106) in owners with close contact to their animals (OR = 8.07, CI 95%; 0.476, 137.014). The logistic regression analysis showed that 85.71% (6/7) of the respondents previously having malaria-like symptoms were found to be significantly associated with owning seropositive animals (OR = 78.74, CI 95%; 8.419, 736.569). Based on the present findings, an estimated economic loss due to camel brucellosis was found to be 429,351.48 ETB (21,467.56 US $) for each individual infected camel with age above 4 years. This pilot assessment indicated high economic burden to the pastoral community and on national livestock industry at large. Lack of awareness about zoonotic diseases together with existing habit of raw milk consumption and close contact with animals can serve as means of Brucella infection to human beings. Thus, there is a need to design and implement control measures aiming at preventing further spread of the disease both in animal and nomadic pastoralists, and minimize economic loss due to camel brucellosis in this agro-pastoral region.

Keywords: Brucellosis, Camel, Economic loss, Public health

Cite this paper: Habtamu T. T., Richard B., Dana H., Kassaw A. T., Camel Brucellosis: Its Public Health and Economic Impact in Pastoralists, Mehoni District, Southeastern Tigray, Ethiopia, Journal of Microbiology Research, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2015, pp. 149-156. doi: 10.5923/j.microbiology.20150505.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Brucellosis is one of the most widespread diseases in the world with serious zoonotic and economic implication. According to the Office International des Épizooties (OIE), it is the second most important zoonotic disease in the world, accounting for the annual occurrence of more than 500,000 human cases [1]. Brucellosis can affect almost all domestic species, and cross transmission can occur between cattle, sheep, goats, camels and other species [2], causing significant reproductive losses in sexually mature animals [3]. The disease is manifested by late term abortions, weak calves, stillbirths, infertility and characterized mainly by placentitis, epididymitis and orchitis. Brucella melitensis, B. abortus and B. suis are zoonotic pathogenic species which can also infect humans. B. canis may cause infections in immuno-suppressed individuals [4, 5].The disease in camels can be caused by B. abortus, B. melitensis and B. ovis [6]. Different studies showed that B. abortus and B. melitensis are the most frequently isolated from milk, aborted fetus and vaginal swabs of diseased camels [7, 8] and the transmission of brucellosis depends on the Brucella species being prevalent in other animals sharing their habitat and on husbandry [9]. Camels are not known to be primary hosts of Brucella, but they are susceptible to both B. abortus and B. melitensis. Consequently, the prevalence depends upon the infection rate in primary hosts being in contact with them. Brucellosis may spread from camels to humans, especially via milk.Brucellosis in human is common in rural areas because farmers live in close contact with their animals and often consume fresh unpasteurized dairy products. However, the vending of dairy products may also bring the disease to urban areas [5, 10]. Brucellosis is widely distributed in Afar region, with small ruminants remaining the most prevalent hosts. Previous work in different districts of the region has revealed a prevalence in human ranging from 0 -11.7% [11] and in camels, overall prevalence rates of 4.4% [12] and 4.2% [13] in different camel rearing areas of Ethiopia.The economic and public health impact of brucellosis remains of concern in developing countries [14]. In Ethiopia, annual losses from brucellosis among cattle have been estimated to be 88,941.96 ETB at Chaffa State Farm Wollo [15]. However no information is available regarding economic losses due to camel brucellosis. The disease can generally cause significant loss of productivity through late first calving age, long calving interval time, low herd fertility and comparatively low milk production in camels. The disease poses a barrier to export and import of animals constraining livestock trade and is an impediment to free animal movement [16].B. melitensis is considered to have the highest zoonotic potential, followed by B. abortus, and B. suis. The disease presents as an acute or persistent febrile illness with a diversity of clinical manifestations in humans [17]. Brucellosis is transmitted to humans mainly by direct contact with infected livestock and the consumption of unpasteurized contaminated milk and dairy products [9].In pastoral communities, the traditional habits of raw milk consumption, handling of aborted materials, manipulation of reproductive excretions with bare hands, and herding of a large number of animals mixed with other animals, are widely practiced. As the disease has veterinary, public health and economic importance, it is necessary to assess the current status among camels in selected districts of the Afar region. Considering the scarcity of information regarding epidemiological information of the disease, the economic and public health impact of camel brucellosis in Mehoni, the present study was undertaken with the following objectives: √ To determine the sero-prevalence of camel brucellosis in Mehoni district,√ To identify potential risk factors associated with animal and human infection,√ To estimate economic losses due to camel brucellosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

- A cross-sectional study was carried out from May 2014 to April 2015 in Mehoni district, north eastern part of Ethiopia which is located in south eastern Tigray. Mehoni is situated approximately between 130151 and 130301N and 390301 and 390551E longitude, 200 km to south east of Mekelle, the capital of Tigray [18].

2.2. Study Animals and Sample Size

- Camel population found in three peasant associations of Mehoni district (Mechare, Hawelti and Hade’alga) was represented the study population. They were not vaccinated against brucellosis. Camels were allotted to two groups according to their ages based on Abebe et al. [19] and Wesinew et al. [20] with a slight modification. The sample size required to determine the prevalence of camel brucellosis was determined by following standard formula recommended by Thrustfield [21]. N=1.962 Pexp (1-Pexp)/D2With 5% desired precision, at 95% confidence level and with expected prevalence of 50%, a total of 384 serum samples was supposed to be collected proportionally from three selected peasant associations of the study district, however to increase the precision, the sample size has been increased to be 415.

2.3. Blood Sample Collection

- Blood samples were collected aseptically from jugular vein using 10ml disposable needles and vacutainer tubes and then brought to laboratory in an icebox. At the laboratory, blood samples were kept overnight to clot in slant position at room temperature. Then the separated serum was carefully collected in cryovial without mixing with the clotted blood. The serum was stored at -20°C until further processing took place.

2.4. Serological Examination

- All the serum samples collected were initially screened by Rose Bengal plate test (RBPT)for the presence of Brucella antibodies using RBPT antigen (Institut Pourquier 325, rue de la galèra 34097 Montpellier cedex 5, France) according to standard procedures described by Nilson and Dukan [22]. All sera samples were further tested by complement fixation test (CFT) using Standard Brucella abortus antigen (CVL, New Haw, Weybridge, Surrey KT15 3NB, UK) as per the method described by Alton et al. [23] and by OIE [24]. The reading was as complete fixation (no hemolysis) with water clear supernatant was recorded as + + + +, nearly complete fixation (75% clearing) as ++ +, partial hemolysis (50%) + + and some fixation (25% clearing) as +. Complete lack of fixation (complete hemolysis) was recorded as 0. For positive reactions final titration was recorded. Brucella seropositive camels are those with both positive RBPT and CFT results. Both tests were performed at National Veterinary Institute, Debreziet, Ethiopia.

2.5. Questionnaire Survey

- A questionnaire survey was administered to one-hundred twenty willing respondents whose camels were included in the study with the help of local language translator. The information gathered relates to animal risk factors like history of abortion, contact with other ruminants, camel rearing experience, and public risk factors like consumption of raw milk, handling of aborted foetuses, contact to vaginal discharges of infected camels and knowledge about brucellosis and its zoonotic importance. In addition, they were interviewed for economic related factors such as abortion, cost of replacement, decreased milk production and reduced fertility.

2.6. Data Management and Analysis

- Both serological test result and questionnaire data were entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and descriptive statistics were employed using STATA software version 16 to analyze majority of the data collected by questionnaire. Odds ratio and univariate logistic regression were used to rule out whether there is significant association between prevalence of camel brucellosis and different groups of animal and human risk factors.

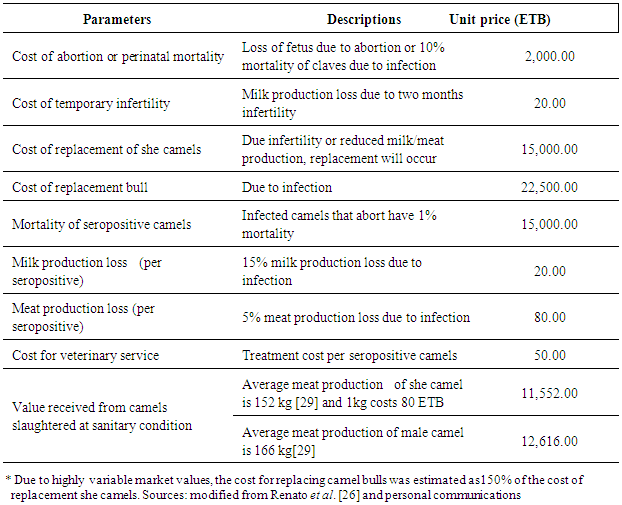

2.7. Parameters to Calculate Economic Losses

|

3. Results

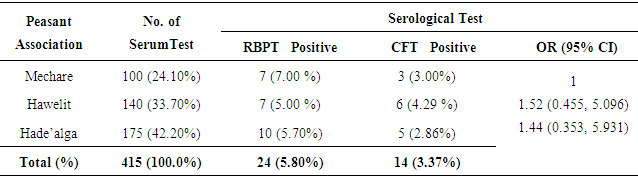

3.1. Brucella Seroprevalence

- In this study, 415 sera were collected from three peasant associations (Mechare, Hawelity and Hade’alga) (Table 2). From the total serum sample collected, 24 animals (5.80%) were screened as seropositive reactors using RBPT. These seropositive reactors were subjected for further CFT confirmation and accordingly, 14 (3.37%) overall seropositive reactors were detected (Table 2).

|

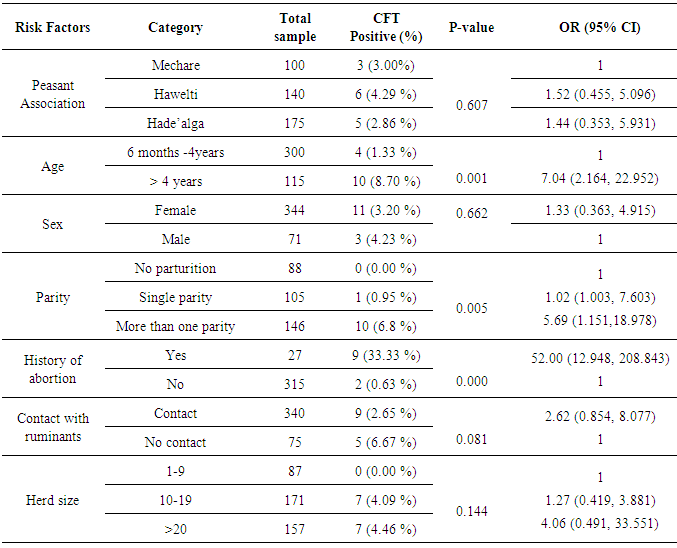

3.2. Potential Risk Factors of Camel Seropositivity

- The univariate logistic analysis of the potential risk factors indicated high significant association of brucellosis with different age groups (OR = 7.04, CI 95%; 2.164, 22.952), parity (OR =5.69, CI 95%; 1.151, 18.978) and history of abortion (OR = 52.00, CI 95%; 12.948, 208.843). Camels with greater than 4 years old are more susceptible than young camels between 6 month and 4 years, and similarly camels with high parity number and history abortion showed significant risk of Brucella infection (Table 3). Camels found in the peasant association ‘Hawelti’ and Hade’alga were 1.5 and 1.4 times more likely to be affected by Brucella infection as compared to Mechare (OR =1.52, CI 95%; 0.455, 5.096 and OR= 1.44, CI 95%; 0.353, 5.931), respectively. However, the seroprevalence of brucellosis with regard to peasant associations was not statistically significant (Table 3).

|

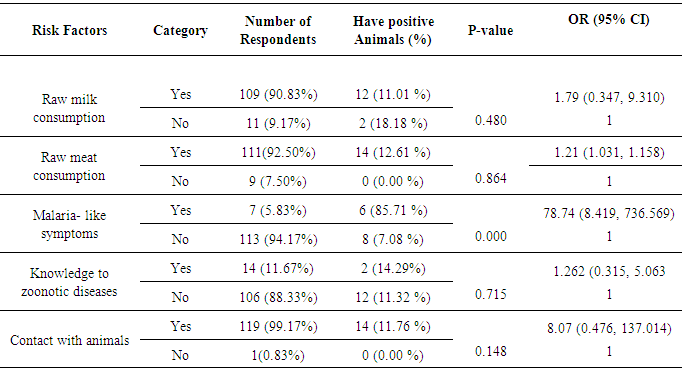

3.3. Questionnaire Survey for Public Health Risk Factors

- A total of 120 camel owners, whose animals included in this study, were interviewed based on their willingness to participate in the survey. Based on the interview, 90.83% (109) of the respondents stated that they drank fresh raw milk regularly and owned 11.01 % (12) of seropositive camels. The logistic regression analysis of respondents who stated having malaria-like symptoms (6, 85.71%) found to be significantly associated with owning seropositive animals (OR = 78.74, CI 95%; 8.419, 736.569) (Table 4).

|

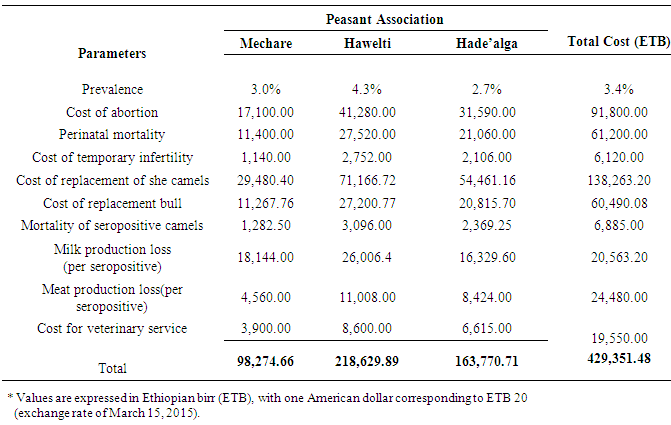

3.4. Economic Loss Due to Camel Brucellosis

- Based on the current sero-epidemiological data, an estimated economic loss due to camel brucellosis in the three peasant associations of Mehoni district has been calculated and several parameters including abortion and perinatal mortality rates, temporary infertility, replacement costs, mortality, veterinary costs, milk and meat losses were considered in the model. Camel brucellosis in the three peasant associations results in an estimated loss of 429,351.48 ETB (21,467.56 US $) for each individual infected camel above 4 years of age, respectively. The highest estimated economic loss due to camel brucellosis was seen in Hawelti (218,629.89 ETB) with a sero-prevalence of 4.3% followed by Hade’alga (163,770.71 ETB) with 3.0% prevalence, and economic loss due to cost of replacement of she camels (138,263.20 ETB) and cost of abortion (91,800.00 ETB) were represented top among the parameters taken (Table 5).

|

4. Discussion

- Brucellosis is a serious zoonotic disease affecting man and all domestic animals including camels. It is considered as one of a widespread zoonotic disease that still of veterinarian, public health and economic concern in many developing countries including Ethiopia [30-32]. The sero-prevalence of camel brucellosis in this study was 3.37% which is in close agreement with Bekele [33] and Teshome et al. [13] who reported prevalence rates of 0.4-2.5%, and 4.2%, respectively in Borena and Oromia region, and with Ghanem et al. [2] who reported a prevalence of 3.1% in Somalia. As most of camels are kept by nomadic people despite the variation in region or locality where all areas practice extensive farming system which agrees with the report of Abbas and Agab [34] that seroprevalence was low in this study. In contrast to the present study, a lower sero-prevalence (0.53%) has been reported by Gessesse et al. [35], in South East Ethiopia and relatively higher sero-prevalence of 5.4% by Wesinew et al. [20] in the Afar National Regional State in northeastern Ethiopia and (7.6%) by Sisay et al. [36] in different districts of Afar region. These varying reactor rates for camel brucellosis in different regions might be due to varying in husbandry and management practices, susceptibility of the animal, presence of the reactor animals in the region, absence of veterinary service, lack of awareness by the nomads about the disease and the pastoralists’ movement from place to place. Brucellosis infection may occur in animals of all age groups, but persists commonly in sexually mature animals. Younger animals tend to be more resistant to infection and frequently clear infections, although a few latent infections may occur [37]. The present study showed that there was highly significant association in different age groups in that adult camels greater than 4 years were about seven times more at risk in acquiring infection than young camels (between 6 months to 4 years)(OR = 7.04, 95% CI; 2.164, 22.952). The low sero-prevalence in young camels might be because of maternal immunity. Susceptibility appears to be more commonly associated with sexual maturity and risk of infection increases with pregnancy as the stage of pregnancy increases [38]. There was no statistically significant difference between the sex groups in the current study and this finding was in line with the report by Wesinew et al. [20], however it disagrees with the findings of Adamu and Ajogi [39] and Junaidu et al. [40], both of whom reported a significantly higher seroprevalence of brucellosis among female camels.In the present study, significantly higher seroprevalence of 33.33% (9) was observed in aborted camels (OR = 52.00, 95% CI; 12.948, 208.843) which are in close agreement with the findings of Mohammed [30] where he reported sero-prevalence of 40% in camels with abortion in and around Dire Dawa city, Eastern Ethiopia. There was also statistically significant association between parity and the sero-prevalence of the disease. Those she-camels with more than one parity were about 6 times more at risk of being seropositive to Brucella infection than with no parturition (OR = 5.69,95% CI; 1.151, 18.978), where as having single parity was 1.02 times more at risk of being seropositive than with no history of parturition. The present study is therefore, in consistent with the previous study by Bekele [33] where higher reactor rate was recorded in camels with more than one parity number as compared to other camel groups. The questionnaire survey has provided information regarding the knowledge and practices of camel keepers about brucellosis in the study area. From a total of 120 camel owners, whose animals included in this study, about 91% (109) stated that they drank fresh raw milk regularly, and 11.01% (12/109) of them owned seropositive camels. Most of them believed that camel milk to possess superior storage life and medicinal properties and they didn’t have any knowledge about the transmission of brucellosis from consumption of raw milk, delivery assistance, cleaning newborns, assisting suckling and carrying the newborn from field to home without any protection. From those owners in close contact with their animals (119), about 11.76% (14) were found to be eight times more likely at risk to be infected by Brucella as compared to those do not have (OR = 8.07, CI 95%; 0.476, 137.014). This low awareness is a limiting factor if control strategies are to be implemented, and this may also predispose the community for infection.Unfortunately, infected farmers with symptoms of undulating fever and joint pain very rarely seek medical help, and if they do, the fever is usually ascribed to malaria or typhoid, therefore human brucellosis is likely to be greatly under-diagnosed [35]. In this study, the logistic regression analysis showed that respondents having malaria-like symptoms so far (85.71%, 6/7) were found to be significantly associated with owning seropositive animals, and they were about 79 times more likely been infected by Brucella organism than those did not have (OR = 78.74, CI 95%; 8.419, 736.569). Based on the present sero-epidemiological finding, an estimated economic loss due to camel brucellosis in the three peasant associations of Mehoni district has been calculated and was found to be 429,351.48 ETB (21,467.56 US $) for each individual infected camel above 4 years of age. Among peasant associations, the highest estimated economic loss due to camel brucellosis was seen in Hawelti (218,629.89 ETB) with a sero-prevalence of 4.3% followed by Hade’alga (163,770.71 ETB) with 3.0% prevalence, and economic loss due to cost of replacement of she camels (138,263.20 ETB) and cost of abortion (91,800.00 ETB) were represented top among the parameters taken. This study provided a pilot assessment of economic losses associated with camel brucellosis in Mehoni, indicating high economic burden to the pastoral community and on national livestock industry at large, which is a major component of the national GDP.In conclusion, brucellosis is an important zoonosis of worldwide distribution and a considerable cause of reproductive losses in animals including camels. The overall seroprevalence of camel brucellosis observed in this study was not high. Since this low prevalence is not as a result of informed policy, it needs due attention because of the public health significance of the disease and there is no guarantee that it will continue unchanged. It is therefore an important period of consolidation for these camel owners and local authorities to keep the disease burden low. In this study, different age groups, parity number and history of abortion showed statistically high significant association with the prevalence of the disease; however, the association with different peasant associations, sex, herd size and species of the animal was not statistically significant except a slight significant difference in camels co-exist with small ruminants. Lack of awareness about zoonotic nature of brucellosis together with existing habit of raw milk consumption and close contact with animals can serve as means of infection to human beings. This study also provided a pilot assessment of estimated economic losses associated with camel brucellosis, indicating high economic burden to the pastoral community and on national livestock industry at large, which is a major component of the national GDP.Based on the above facts, the following points should be considered in controlling of the disease:• Further epidemiological studies like isolation and identification of the species and biotypes of Brucella responsible for camel and human infection in the region should be conducted.• Adequate brucellosis control programs in small ruminants would contribute to the reduction of the disease prevalence in camels.• Thus, there is a need to design and implement control measures aiming at preventing further spread of the disease in this region.• There is also a need for further study to critically assess the economic impact of this disease in other parts of the country to estimate national economic losses.• Additionally, awareness about modern animal husbandry, disease prevention and risk of zoonotic diseases is quite necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author is grateful to acknowledge the USAID in collaboration with Colorado State University and Mekelle University for financial support and providing facility to conduct this project, respectively. It would be pleased to thank National Veterinary Institute (Ethiopia) for sample processing and Mehoni District for all their contribution during the study period.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML