-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Microbiology Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5885 e-ISSN: 2166-5931

2014; 4(5): 175-179

doi:10.5923/j.microbiology.20140405.01

Microbiological Quality of Smoked Mackerel (Trachurus trachurus), Sold in Abomey-Calavi Township Markets, Benin

Kpodekon Marc1, Sessou Philippe1, Hounkpe Eustache1, Yehouenou Boniface2, Sohounhloue Dominique2, Farougou Souaïbou1

1Research Unit on the Biotechnology of Animal Production and Health, Laboratory for Research in Applied Biology, Polytechnic of Abomey-Calavi, University of Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Benin

2Laboratory for Study and Research in Applied Chemistry, Polytechnic of Abomey-Calavi, University of Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Benin

Correspondence to: Farougou Souaïbou, Research Unit on the Biotechnology of Animal Production and Health, Laboratory for Research in Applied Biology, Polytechnic of Abomey-Calavi, University of Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Benin.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) is a highly perishable but important source of animal protein in west African countries in general and particularly in Benin. To avoid its deterioration after capture, women use various processes to preserve this fish before selling it in local markets. Smoking is one of the most widely used preservation processes used in Benin. To assess the microbiological quality of smoked T. trachurus sold to consumers, sampling was done in the southern part of Benin. The samples were collected aseptically at the point of sale and transported to the laboratory for analysis. A total of 30 smoked T. trachurus samples were collected from 6 randomly selected vendors in three major markets in Abomey-Calavi township where most of the students of the University of Abomey-Calavi go to buy fish. The ISO and International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods standard methods were used for laboratory analysis and interpretation of results. A survey was also undertaken in 4 major Abomey-Calavi township markets to assess the processing and selling conditions for T. trachurus. The results of the survey showed a total lack of hygienic practices for the smoking, storage and sale of T. trachurus. The total viable counts of the majority (60 to 83.5%) of the samples were high: 5.9 x 106 ± 9.5 x 106 cfu/g for total mesophilic aerobic flora, 8.0 x 104 ± 1.8 x 105 cfu/g for thermotolerant coliforms, 3.7 x 102 ± 6.5 x 102 cfu/g for yeasts, 4.0 x 103 ± 1.4 x 104 cfu/g for moulds. In addition, 6.7% of the T. trachurus samples were contaminated with sulphite reducing anaerobes (0.1 ± 0.5 cfu/g). Salmonella spp and Staphylococcus aureus were not detected. These results suggest that efforts are needed to improve the microbiological quality of smoked mackerel fish sold in Abomey-Calavi and similar studies should be done elsewhere in Benin.

Keywords: Trachurus trachurus, Mackerel, Smoking, Abomey-Calavi, Benin

Cite this paper: Kpodekon Marc, Sessou Philippe, Hounkpe Eustache, Yehouenou Boniface, Sohounhloue Dominique, Farougou Souaïbou, Microbiological Quality of Smoked Mackerel (Trachurus trachurus), Sold in Abomey-Calavi Township Markets, Benin, Journal of Microbiology Research, Vol. 4 No. 5, 2014, pp. 175-179. doi: 10.5923/j.microbiology.20140405.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Although Benin has the potential to produce more fish and fish products, this has not occurred. This gap is filled by imports which are becoming more important [1, 2]. Fish is indeed the most important source of animal protein in the diet of the people of Benin. In tropical regions, particularly in West Africa, traditional processes such as drying, salting, smoking, fermentation and combinations of these treatments are used for fresh fish preservation while in developed countries the practice of cold storage limits the problem posed by the extreme perishability of fish [3]. Today, smoking is the traditional and still primary method of preserving fish in Benin [4]. This process requires a great deal of human handling, which can be a frequent source of contamination by ubiquitous pathogens [5]. Also the traditional methods for preservation of the fish after smoking promote the growth of other pathogens [6]. Indeed, pathogens and chemical contaminants in smoked fish pose potentially serious threats to the health of consumers [7]. Other concerns include contamination by fungi, particularly Aspergillus flavus, which, under certain conditions, secretes aflatoxins that have a hepatotoxin that may lead to liver cancer [8, 9]. Mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) is an important source of animal protein in Benin. To preserve it, women traditionally use various techniques to prepare this fish for sale to consumers with smoking being the most common method. The published research from Benin, to our knowledge, has focused only on fermented fish [10]. Also, no study was conducted on smoked fish produced in Benin and their potential risks on consumer’s health.The objective of this study was to evaluate the microbiological quality of mackerel smoked and sold in markets in Abomey-Calavi township, which are mostly commonly frequented by students who, in particular, consider this product as a ready-to-eat food.

2. Material and Methods

- The study was carried out in two steps. The first step was a survey to assess production processes for mackerel and the conditions under which the fish was sold in 4 markets in the township of Abomey-Calavi: Akassato, Calavi Tokpa, Cocotomey and Godomey. The second step was to evaluate microbiological quality of smoked mackerel samples from three of the surveyed markets.

2.1. The Survey

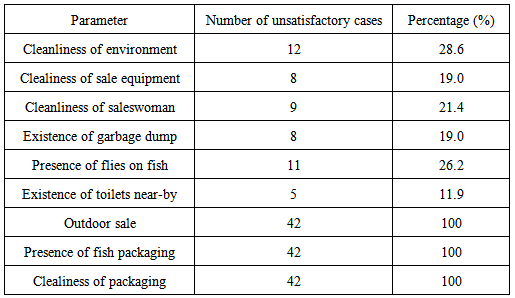

- The production and conditions of sale of smoked mackerel was assessed through a structured survey conducted and supported by a written questionnaire which was administered to all of the mackerel sellers found in the daily markets. In total, 42 sellers of smoked mackerel were surveyed. The written questionnaire was related to the age, sex and level of education of the seller, the mackerel production process, the type of water used to wash the mackerel, the compliance with good hygiene practices, the nature of the vendor’s set-up (outdoors or in a shelter), supply sources of fish, preserving method of the fresh fish and unsold smoked fish, production capacity and volume of sales. The degree of fish sanitation was evaluated through visual observation of the cleanliness of the sale’s environment, the vendor, the product, the presence of flies on fish or around the sale’s point, the existence of a storage place for garbage and the existence of toilets near the sale’s point.

2.2. Sampling of Fish

- Sampling of fish for microbiological assessment was done in accordance with the procedures of the ICMSF [11] in three markets (Calavi Tokpa, Cocotomey and Godomey). Smoked fish samples were collected from two vendors targeted randomly per market. The sampling plan was as follows: 5 samples of smoked fish from each seller were put into individual Stomacher bags (BA604l cpg Standard bag, Seward Limited, West Sussex, United Kingdom). Bags containing the samples were carefully labeled (market, identification number of fish sample, date of sampling, seller, time of sampling) and then transported in a cooler containing dry ice to the laboratory no later than 4 hr of sampling time and fish samples were immediately analyzed.

2.3. Microbiological Analysis

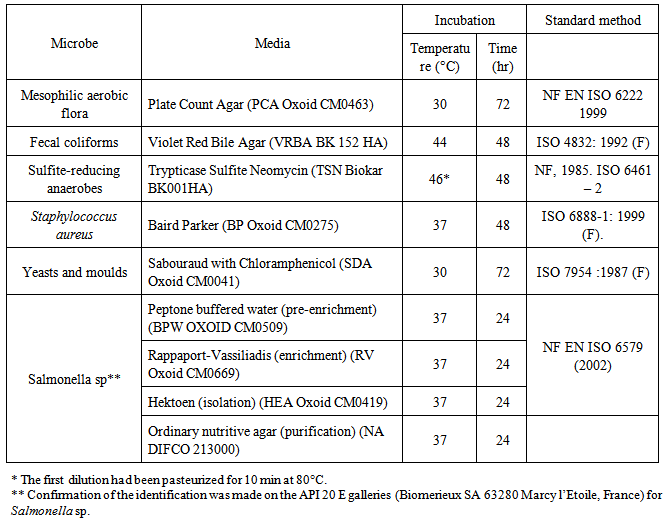

- Superficial and deep parts (skin and or flesh from head, tail and middle regions) of the smoked fish were collected using sterile forceps and knives...Twenty five (25) g of each sample (steaks cut from the head, middle and tail region of the fish) were weighed into a sterile Stomacher bag. The mixture constituted of 25 g of fish and 225 mL of buffered peptone water (BPW OXOID CM0509, Typical formula: peptone 10g/L, sodium chloride 5g/L, disodium phosphate 3.5g/L, potassium dihydrogen phosphate 1,5g/L, pH=7.2 ± 0.2 at 25°C, LTD, Bashingstoke, Hampshire, England) represented the stock solution which was used to prepare the decimal dilutions [10, 12, 13].Serial dilutions of the fish samples varied between 10-1 and 10-7. The diluent used was buffered peptone water (BPW OXOID CM0509, Typical formula: peptone 10g/L, sodium chloride 5g/L, disodium phosphate 3.5g/L, potassium dihydrogen phosphate 1,5g/L, pH=7.2 ± 0.2 at 25°C, LTD, Bashingstoke, Hampshire, England). The main selective media used for isolation and enumeration of colonies are described in Table 1. The isolation and enumeration of mesophilic aerobes, total coliforms, fecal coliforms, sulphite-reducing anaerobes, Staphylococcus aureus, yeasts and moulds were carried out according to standard techniques [11-13].

|

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- Statistical analysis was carried out with SAS Software (SAS Institute Inc., Version 6, 4th ed, Cary, NC, USA, 1989) and several procedures were used. The procedure for the generalized linear model (Proc-GLM) was used for the analysis of the variance and the means of loads of three independent replicate trials were then calculated and compared using a Z-test with Statistica version 6 software (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Conditions for Production and Sale of Fish

- Fish were smoked and sold the same day by 100% of the producers or sellers. All vendors reported smoking fish themselves at home without probably any understanding of good practices of hygiene. All fish were hot smoked without gutting, drying or salting of the fish. About 95% of the producers reported using well water that had not been tested for microbiological quality. In general, the production and sale of fish were done in environments that were not sanitary. In fact, fish were most likely washed with compromised quality water, sold in the open air without packaging, sometimes near piles of garbage and toilets with a large presence of flies around the fish. Thus, 28% of vendors were in an unhealthy environment, 19% used uncleaned equipment, 21% of the vendors were not themselves clean, garbage was present close to 19% of the fish stalls, flies were present at 26% of the fish for sale, and toilets were only available to about 12% of vendors. All vendors were outside with fish left open with no packaging (Table 2).

|

3.2. Microbiological Quality of Smoked Fish

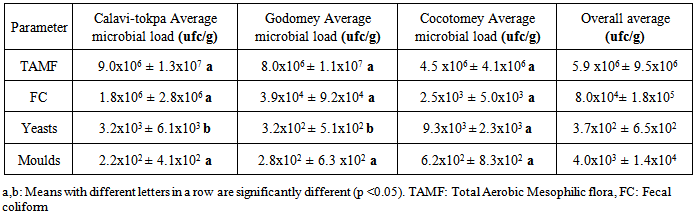

- The fish samples collected from the three markets were highly contaminated with microbe with mean cell counts of 5.9 x 106 ± 9.5 x 106 cfu/g for total mesophilic aerobic flora; 0.8 x 105 ± 1.8 x 105 cfu/g for thermotolerant coliforms, 3.7 x 102 ± 6.5 x 102 cfu/g for yeasts; 0.4 x 104 ± 1.4 x 104 cfu/g for moulds and 0.1± 0.5 cfu/g for sulphite-reducing anaerobes, respectively (Table 3). The microbial loads of fish from these markets generally exceed the limit (106 cfu/g) for total microbial load as required by many Western regulatory systems [8].

|

4. Conclusions

- Assessment of the microbiological quality of smoked mackerel sold in the markets of the Township of Abomey-Calavi in Benin showed that the conditions for their production and sale suggested that producers and vendors were not following good hygiene practices. However, pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella sp, were not identified in the samples analyzed. However, two samples of fish samples were contaminated with Clostridium spores that could be spores of pathogenic Clostridium botulinum type E or Clostridium perfringens. It is therefore important that actions be taken to improve the situation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are grateful to CUD (Belgium) for financial support. They are also thankful to Doctor Boko Cyrille and Mr Dossa François for technical help.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML