-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Microbiology Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5885 e-ISSN: 2166-5931

2014; 4(4): 170-173

doi:10.5923/j.microbiology.20140404.03

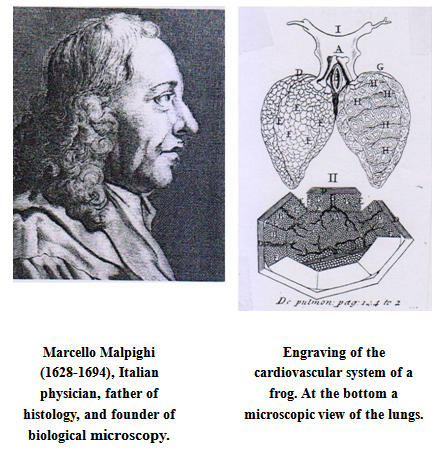

Marcello Malpighi, the Founder of Biological Microscopy

Nāsir pūyān (Nasser Pouyan)

Tehran, 16616-18893, Iran

Correspondence to: Nāsir pūyān (Nasser Pouyan), Tehran, 16616-18893, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Marcello Malpighi Italian physician, founded the science of microanatomy and histology, working with both plants and animals. He conducted microscopic studies of the structure of the liver, skin, lungs, spleen, glands, brain, and discovered capillaries that join arteries and veins postulated by William Harvey. He described the finer structures of many tissues and organs, and was the first to describe the lymph nodes of the spleen (Malpighi an bodies), the embryology of a chick, and graafian follicles. Malpighi and other exponents of the new sciences in bellows, syringes, pipes, valves, and the similar contrivances continued, and spurred careful investigation into individual organs. As an independent thinker, he defied Galen. In his later years he came under the patronage of Pope InnocentXll.

Keywords: Microanatomy, Histology, Animals, Plants

Cite this paper: Nāsir pūyān (Nasser Pouyan), Marcello Malpighi, the Founder of Biological Microscopy, Journal of Microbiology Research, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 170-173. doi: 10.5923/j.microbiology.20140404.03.

- Marcello Malpighi, Italian anatomist was one of the two giants of seventeen-century microscopic study1. His greatest contribution was the discovery of the capillaries2, the minute vessels which carry blood from the arteries to the veins, in 1666. Malpighi's important achievement, accomplished independently by Dutch microscopist and father of microbiology Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), completed the missing link in the circulation of the blood as described earlier by the brilliant British physician and anatomist William Harvey (1578-1657) [1]. Indeed, Harvey demonstrated that blood circulated through the body and was pumped by the heart, and discussed his findings in his lectures in 1616 and published them in “Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus” (1628) [2].Malpighi's other work included studies of the blood, lymph nodes, and spleen, and of the tissues of numerous plants and animals [3]. He also described the embryology of a chick, graafian follicles, vesicular structure of the lungs, the glomerular tufts of the kidneys, and the Malpigian bodies of the spleen.In Europe, from about the 14th century, a renaissance (or “re-birth”) of interest in the arts and sciences spread from Italy across Europe. This envolved a rediscovery and also some criticism of classical learning. Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), “Italian scientist, founder of modern physics and of telescopic astronomy, and champion of freedom in scientific research”, for example through using a telescope, pressed the universe. In this new spirit of inquiry, people such as Leonardo da Vinchi (1452-1519), Italian artist, engineer, and scientist, and Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) outstanding Belgian anatomist and surgeon who wrote “De humani corporis fabrica” began to dissect human corpses, a practice that had not previously been very common, and to discover the structures and working of the human body. Following pioneering work by Matteo Realdo Colombo (1516-1559), Italian anatomist who gave the earliest description of pulmonary circulation, and Andrea Cesalpino (1519-1603), Italian botanist and physician who described the circulation, and Harvey's simple but great discovery contradicted the Galenic tradition of blood being produced from food and drink and consumed in the tissues3. In the mean time, Harvey's simple experiments met much criticism [4]. Malpighi as an independent thinker defied the authority of Galen, but his views excited such passion that he was physically assaulted by two masked colleagues at the University of Pisa.Malpighi, regarded the founder of biological microscopy, also reported his findings to the “Philosophical Transactions”, Journal of the “Royal Society” in London. His contributions in both botany and biology (the science of life) affected the entire science of microscopy [5].He was the first to confirm by microscopic examination of the lungs and the capillaries which Harvey postulated. Malpighi also corrected the previous view the lungs were of muscular consistency by showing that they consisted of many extremely thin-walled compartments connected to the smallest branching of the windpipe [6].

1. The highlights

When he was around 38 years old, decided to dedicate his free time to anatomical studies.

When he was around 38 years old, decided to dedicate his free time to anatomical studies.  Cell, a term used by Robert Hooke, in his Micrographia (1665) to refer to the compartments that he noted in a cork under the microscope. Two decades later the cell structure of plants was observed by Malpighi.

Cell, a term used by Robert Hooke, in his Micrographia (1665) to refer to the compartments that he noted in a cork under the microscope. Two decades later the cell structure of plants was observed by Malpighi.  He wrote on the lungs in 1663.

He wrote on the lungs in 1663.  In 1669, the first microscopic dissection of an invertebrate, a silkworm, was performed by him.

In 1669, the first microscopic dissection of an invertebrate, a silkworm, was performed by him.  The movement of sap in plants (plant physiology) was first proposed by Malpighi in 1670.

The movement of sap in plants (plant physiology) was first proposed by Malpighi in 1670.  He studied the molds on fruits, cheese and wood in 1679.

He studied the molds on fruits, cheese and wood in 1679.  The nodules found to contain “Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria” were first observed by Malpighi in 1686 [7].

The nodules found to contain “Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria” were first observed by Malpighi in 1686 [7].  Malpighi showed microscopic views of the lung and its network of capillaries (1686).

Malpighi showed microscopic views of the lung and its network of capillaries (1686).

He described the finer structures of many tissues and organs.

He described the finer structures of many tissues and organs. William Harvey discovered the circulation of the blood assumed that there were capillaries even though he could not see them. Malpighi accomplished the microscopic structures after Harvey's death [8].

William Harvey discovered the circulation of the blood assumed that there were capillaries even though he could not see them. Malpighi accomplished the microscopic structures after Harvey's death [8].  He identified blood corpuscles as “fat globules”. (Anton van Leeuwenhoek was the first to recognize blood corpuscles.)

He identified blood corpuscles as “fat globules”. (Anton van Leeuwenhoek was the first to recognize blood corpuscles.)  Carl Linaeus (1707-1778), Swedish naturalist and physician and father of systematic binomial taxonomy, named the genus Malpighi in honor Malpighi's work with plants.

Carl Linaeus (1707-1778), Swedish naturalist and physician and father of systematic binomial taxonomy, named the genus Malpighi in honor Malpighi's work with plants.  He looked through the microscope at everything imaginable, indeed hardly an organ escaped from his discerning eye [9].

He looked through the microscope at everything imaginable, indeed hardly an organ escaped from his discerning eye [9].  Around the turn of seventeenth century, although a Dutch spectacle maker made the compound lens and inserted it in a microscope, and Galileo had applied the principle of the compound lens to the making of his microscope patented in 1609, its possibilities as a microscope had remained unexploited for around 50 years, until Robert Hooke (1635-1703), brilliant British experimental philosopher developed the early compound microscope. Following this, Malpighi, Hooke and two other early investigators associated with the “Royal Society, in London, Nehemiah Grew, and Anton van Leeuwenhook were fortunate to have virtually untried tools in their hands as they began their investigations.

Around the turn of seventeenth century, although a Dutch spectacle maker made the compound lens and inserted it in a microscope, and Galileo had applied the principle of the compound lens to the making of his microscope patented in 1609, its possibilities as a microscope had remained unexploited for around 50 years, until Robert Hooke (1635-1703), brilliant British experimental philosopher developed the early compound microscope. Following this, Malpighi, Hooke and two other early investigators associated with the “Royal Society, in London, Nehemiah Grew, and Anton van Leeuwenhook were fortunate to have virtually untried tools in their hands as they began their investigations.  Robert Hooke was the first to observe and describe the basic units of plant structure, which he called “cell”. Stimulated by Hooke's researches, Marcello Malpighi, and Nehemiah Grew laid a substantial foundation for the plant anatomy.

Robert Hooke was the first to observe and describe the basic units of plant structure, which he called “cell”. Stimulated by Hooke's researches, Marcello Malpighi, and Nehemiah Grew laid a substantial foundation for the plant anatomy.  Malpighi after dissected a black male, he made some groundbreaking headway into the discovery of the origin of black skin. He found that the black pigment was associated with a layer of mucus just beneath the skin.

Malpighi after dissected a black male, he made some groundbreaking headway into the discovery of the origin of black skin. He found that the black pigment was associated with a layer of mucus just beneath the skin.  He may have been the first person to see red blood cells under the microscope.

He may have been the first person to see red blood cells under the microscope.  Malpighi discovered that insects, particularly, the silk worm do not use lung to breathe, but small holes in their skin called tracheae.

Malpighi discovered that insects, particularly, the silk worm do not use lung to breathe, but small holes in their skin called tracheae.  Under the microscope, he demonstrated the minute vascular structures postulated by William Harvey to connect the smallest arteries to the smallest veins [10].

Under the microscope, he demonstrated the minute vascular structures postulated by William Harvey to connect the smallest arteries to the smallest veins [10].  It was William Harvey's demonstration of the circular of blood flow that led Malpighi to investigate the link between arteries and veins, culminating in his discovery of the capillaries in 1666 [11].

It was William Harvey's demonstration of the circular of blood flow that led Malpighi to investigate the link between arteries and veins, culminating in his discovery of the capillaries in 1666 [11].  Malpighi's discovery of capillaries and other minute structures also justify his being the founder of histology.

Malpighi's discovery of capillaries and other minute structures also justify his being the founder of histology.2. Life

- Marcello Malpighi was born on March 10, 1628 at Crevalcore near Bologna, Italy. The son of a well-to-do parents was educated in Bologna, entered the University of Bologna in 1646 at the age of 17. In a posthumous work delivered and dedicated to the Royal Society in London in 1697, Malpighi says he completed his grammatical studies in 1645, at which point he began to apply himself to the study of peripatetic philosophy. He completed these studies about 1649, where at the persuasion of his mother Frances Natalis he began to study physics. When his parents and grandmother became ill, he returned to his family home near Bologna to care for them [12].Both his parents died when he was 21, but nevertheless, to continue his studies in 1653 was granted a doctorate in both medicine and physiology and appointed as a teacher, whereupon he immediately dedicated himself to further study in anatomy and medicine.Ferdinand Il of Tuscany invited him to the professorship of theoretical medicine at the University of Pisa (1656). It was there that he began his lifelong friendship with Giovanni Alphonso Borelli (1608-1679), Italian physician, mathematician and naturalist who wrote “De motu animalium”, applied mechanics and physical principles to the body, and was a prominent supporter of the “Academia del Cimento,” one of the first scientific societies. Family responsibilities and his poor health, in 1659, promoted him to return to the University of Bologna, where he continued to teach and to research with his microscope. His views evoked increasing controversy and dissent. Hindered by the hostile environment of Bologna accepted a professorship in medicine at the University of Messina in Sicily, on the recommendation there of Borelli, who was investigating the effects of physical forces on functions. He was also welcomed by Viscount Giacomo Ruffo Francavilla, a patron of science and a former student, whose hospitality encouraged Malpighi in furthering his career. After four years at Messina, he returned to Bologna (January 1667).Malpighi's work at Missina, attracted the attention of the Royal Society in London, whose secretary Henry Oldenberg extended him an invitation to correspond with him (1668). Malpighi's work was there after published periodically in the form of letter in the Journal Philosophical Transactions of the “Royal Society” in London. In 1669, Malpighi was named an honorary member, the first such recognition given to an Italian. From then on, all his works were published in London. In Bologna, Malpighi conducted many studies and continued his general practice and professorship. During the last decade of his life, Malpighi was beset by personal tragedy, declining health and the climax opposition to him. His villa was burned, his apparatus and microscope shattered, and his papers, books, and manuscripts destroyed [13].Pope Innocent Xll invited him to Rome in 1691 as papal physician (papal archiater), and he was further honoured by being named a count. He taught medicine and wrote a long treatise regarding his studies which he donated to the “Royal Society” in London. He died of stroke in Rome on September 29, 1694 at the age of 66. According to his wishes, an autopsy was performed, and the Royal Society published his studies in 1696.Malpighi is buried in the church of the Santi Gregorio e Siro, in Bologna, where nowadays can be seen a marble monument to the scientist with an inscription in Latin remembering-among other things-his “SUMMUM INGENIUM / INTEGERRIMAN VITAM / FORTEM STRENUAMQUE MENTEM/AUDACEM SALUTARIS ARTIS AMOREM” (great genius honest life, strong and tough mind, daring love for the medical art) [14].

3. Works

- Some of Malpighi's outstanding works are:1. “Anatomia Plantarum”, two volume published in 1675 and 1679, an exclusive study of botany published by the Journal “Philosophical Transactions” of the “Royal Society” in London. In his autobiography, Malpighi speaks of this work, decorated with the engravings of Robert White as the most elegant format in the whole literate world.2. “De visceru structura exercitati”.3. “De pulmonis epistolee”.4. “De polypo cordis” (1666), a tritease that is important for understanding blood composition and how blood clots. In this work, he described how the form of a blood clot differed in the right vs. the left side of the heart.5. Dissertatio epistolica de formatione pulli in ovo (1673). In this work Malpighi followed the theory of epigenesis, which held that organisms begin as primitive substance and develop into mature embryos through a series of stages [15].

4. Conclusions and Impact

- Marcello Malpighi, the first great medical microscopist, was contemporary of Anton van Leeuwenhoek. He described the very tiny blood vessels called capillaries which linked arteries to the veins, thereby completing the route for the circulation of blood that had been suggested by William Harvey. Although his contributions had enormous importance to anatomy and pathology, their impact on the practice of medicine was limited, since the concepts and understandings of disease were little advanced by his demonstrations [16]. About two centuries later, Johaness Petter Muller (1801-1858), German scientist-philosopher and pioneering physiologist who proposed the law of specific nerve energies, pioneered the microscopic diseased tissues and cells which is called cellular pathology [17].Malpighi's observations that cork was composed of compartments which he called “cells,” was to be used for the 19th century theory that a cell4 was the basic unit of all living organisms. Later in 1839 (after 145 years), the structure of specialized cell, such as nerve cells and smooth muscle cells was studied by Theodor Schwann (1810-1882), German physiologist who formulated the cell theory, coined the famous phrase “Omnis cellula e cellula” (every cell from a cell). Indeed Malpighi founded the now-familiar idea of the cell as the basic “unit” of life, with all living things made from cells. Schwann's contemporary Rodolf Virchow (1821-1902), German founder of cellular pathology who regarded disease as a cellular response to change, adapted his cell theory to include the newly observed process of cell division, and stated that “All cells come from cells [18],” and completed Malpighi's observations.After Malpighi's researches, microscopic anatomy became a prerequisite for advances in the fields of physiology, embryology and practical medicine. His contributions in scientific studies of life and structure of plants and animals, affected the entire science of microscopy. On the whole, Malpighi could not say what new remedies might come from his discoveries, but he was convinced that microscopic anatomy by showing the minute construction of living things, called into question the value of old medicine. He provided the anatomic basis for the eventual understanding of human physiological changes. His discoveries also helped to illuminate philosophical arguments surrounding the topics of emboitment, pre-existance, epigenesis, and metamorphosis [19].

Notes

- 1. The other giant of microscopic study was Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), Dutch pioneer microscopist, protozoologist and bacteriologist from Delft, Holland, who was the first to observe bacteria and protozoa and whose observations led to the discovery of spermatozoa. (Sebastian, Anton.Dates in Medicine. The Parthenon publishing Group, New York-London, 2000, p.27.)2. Capillary electrometer, an instrument for magnifying minute fluctuations of electrical potential invented by French physicist, Gabriel Jonas Lippman (1845-1921) in 1875. 3. Claudius Galen (129-200), famous Greek physician and prolific writer and the most famous of the Roman doctors who founded the Galenic system of medicine, which was followed for about 15 centuries until the Renaissance when it was questioned by Andreas Vesalius, and Paracelsus (1493-1541), Swiss physician and alchemist who wrote on the nature and causes of diseases. At Galen's time, dissection of human body was illegal, so he dissected animals and transferred the information on the anatomy of, for example, pigs to humans. As each species of animal has its own specific structure, he made some mistakes, but he learned a substantial amount regarding dissection. Galen discovered that blood moved in the body, but not it circulated round the body. (Cochrane, Jennifer. An Illustrated History of Medicine. p.18 and 19.) 4. Cell, is microscopic unit of living matter, containing a nucleus: human tissue is made up of cells.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML