-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Basic Sciences of Medicine

p-ISSN: 2167-7344 e-ISSN: 2167-7352

2025; 13(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.medicine.20251301.01

Received: Oct. 9, 2025; Accepted: Nov. 3, 2025; Published: Nov. 7, 2025

Effect of the Combination of Ethanol Extract of Gumitir (Tagetes erecta) and Jepun (Plumeria Alba) Flowers on Testosterone Levels of Male Wistar Rats Exposed to Cigarette Smoke

Ni Wayan Sri Ekayanti1, Putu Austin Widyasari Wijaya1, Luh Gde Evayanti2

1Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Warmadewa University, Indonesia

2Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Warmadewa University, Indonesia

Correspondence to: Ni Wayan Sri Ekayanti, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Warmadewa University, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

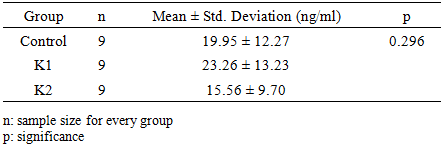

Exposure to cigarette smoke is a significant contributor to male reproductive dysfunction through a key mechanism of oxidative stress induction that leads to Leydig cell damage and decreased testosterone levels. This study aimed to test the protective potential of a combination of ethanol extracts of Gumitir flower (Tagetes erecta), which is rich in carotenoid antioxidants (Lutein), and Jepun flower (Plumeria alba) containing terpenoids and steroids, against cigarette smoke-induced hypogonadism. This study used an experimental method with a posttest control group design approach with a sample of 27 male Wistar rats divided into three treatment groups; Control Group (K1); Toxicity Group (K2), who are only exposed to cigarette smoke for 1 hour every day; and the Intervention Group (K3), which was given a combination of extracts before exposure to cigarette smoke for 1 hour per day. The treatment is administered over a period of 3 weeks. The results showed that exposure to cigarette smoke (K2) in the acute phase can increase plasma testosterone compared to K1. Administration of a combination extract (K3) resulted in lower testosterone levels (15.56 ng/ml) than in the control group (19.95 ng/ml), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.296). Conclusion: The combination of ethanol extracts of Tagetes erecta and Plumeria alba may have androprotective potential against hormonal dysfunction caused by cigarette smoke, but does not provide a significant preventive effect on decreased testosterone levels in the subacute phase, but further research is needed to fully understand its effect.

Keywords: Testosterone, Cigarette smoke, Tagetes erecta, Plumeria alba., Oxidative stress, Wistar Rats

Cite this paper: Ni Wayan Sri Ekayanti, Putu Austin Widyasari Wijaya, Luh Gde Evayanti, Effect of the Combination of Ethanol Extract of Gumitir (Tagetes erecta) and Jepun (Plumeria Alba) Flowers on Testosterone Levels of Male Wistar Rats Exposed to Cigarette Smoke, Basic Sciences of Medicine , Vol. 13 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.medicine.20251301.01.

1. Introduction

- Tobacco use is an essential public health challenge responsible for significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. The composition of cigarette smoke is polypharmacological, containing more than 4,000 types of constituents, including Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH), nicotine, tar, and various heavy metals [1]. This toxic complexity causes biological damage that is multifactorial, affecting almost every organ system, including the endocrine system of male reproduction. The impact of smoking on male fertility has been extensively documented, including decreased semen quality, impaired spermatogenesis, dysfunction of the hormonal system, and reduced testosterone concentration. Testosterone, the primary androgen, is synthesized by Leydig cells in the testes, and its regulation is under the control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis complex.In vivo studies on a model of Wistar rats exposed to nicotine have confirmed that this toxicity significantly lowers testosterone levels and testicular weight, as well as induces genital epithelial cell atrophy and histological distortion in the testes [2]. A decrease in these androgen levels clinically indicates hypogonadism or Leydig cell dysfunction, which underlies the need for therapeutic intervention. Cigarette smoke produces excessive Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) that exceed the neutralising capacity of the endogenous antioxidant system. Uncontrolled ROS causes lipid peroxidation, DNA fragmentation, and triggers cellular apoptosis pathways. This decrease in testosterone levels is directly correlated with an increase in the Oxidative Stress index, which is reflected by a decrease in the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) and Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) in cavernosal tissue [3]. These findings confirm that therapeutic interventions should specifically target oxidative stress mitigation and restoration of endocrine function. Given the dual etiology of testosterone decline (oxidative damage and HPG regulatory dysfunction), phytopharmaceutical approaches that offer multitarget action are promising. Existing studies support the use of antioxidant agents to protect Leydig cells from damage induced by cigarette smoke [3]. Gumitir flower (Tagetes erecta, Marigold) is known to be rich in bioactive compounds, especially flavonoids, polyphenols, carotenoids, and xanthophylls [4]. These flowers are a major source of phytochemicals, particularly Lutein and Zeaxanthin, where Lutein can account for up to 70% of the total carotenoid content [5]. Lutein has been recognized as an effective antioxidant. Other studies have also shown the highest total phenolic and flavonoid content, which correlates with optimal antioxidant activity (e.g., as measured by DPPH and ABTS assays). The flavonoid compounds in Tagetes erecta have been shown to act as free radical antibodies produced explicitly by exposure to cigarette smoke. Therefore, Tagetes erecta serves as a potent cellular protective component in this combination, targeting primary oxidative damage.Jepun flowers (Plumeria alba) also contain antioxidants, especially flavonoids and phenolic compounds [5]. However, the rationale for its incorporation is based on a broader secondary content. Plumeria alba extract has been reported to contain alkaloids, glycosides, tannins, and, crucially, terpenoid compounds and steroids [5]. The presence of terpenoids and plant-based steroids provides a mechanistic basis for potential andromodulatory activity. Plant-based steroid compounds can interact with hormonal signalling pathways in the HPG axis, which regulate the secretion of GnRH, LH, and FSH, and ultimately the synthesis of Testosterone by Leydig cells. Thus, Plumeria alba. It is expected to provide regulatory support and hormonal stabilization. In addition, terpenoids are also often associated with anti-inflammatory effects [6], which are important for counteracting chronic inflammation triggered by the toxicity of cigarette smoke in testicular tissue.This study tested a unique therapeutic synergism hypothesis, in which Tagetes erecta (rich Lutein) is focused on mitigating direct oxidative damage, and Plumeria alba. (containing terpenoids/steroids) is focused on stabilizing and modulating the HPG axis. Although there are data on the antioxidant potential of Tagetes erecta and the phytochemical profile of Plumeria alba, there has been no in vivo investigation that explicitly tested the combined effects of ethanol extracts of Tagetes erecta and Plumeria alba in the context of restoration of testosterone levels in a model of male Wistar rats exposed to cigarette smoke. Based on the phytochemical and pathophysiological rationale described, the main objective of this study is to quantitatively evaluate the effect of administering a combination of ethanol extracts of Tagetes erecta and Plumeria alba flowers on plasma testosterone levels in male Wistar rats exposed to cigarette smoke. The results of this study are expected to provide a scientific basis for the development of multitarget phytopharmaceutical agents for the therapy of male reproductive dysfunction caused by environmental toxicity.

2. Method

- Research DesignThe research used an experimental method with a posttest-only control group design.Research SubjectThis study used 27 male Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus) aged 3-4 months and weighing 300-400 grams. The rats were acclimatised for 7 days before being given treatment. Simplicia ExtractionThe raw materials used are gumitir flower (Tagetes erecta) and Jepun flower (Plumeria alba). The flowers are washed with clean water and then dried in the oven. The simplicia is then mashed and made into a thick extract. Research ProcedureSamples were randomly divided into three treatment groups. Group 1 (K1) served as a control; group 2 (K2) was exposed to cigarette smoke for 1 hour; group 3 (K3) was given gumitir and Jepun flower extract at 200 mg/kg-BW 1 hour before exposure to cigarette smoke. Exposure to cigarette smoke is given for one hour once a day. Treatment was given for three weeks. After three weeks, a 1 mL blood sample from the rats was collected. Testosterone levels are tampered with using the ELISA method. The data is then processed using SPSS version 25.0.

3. Result

- In this study, the results showed that rat testosterone levels in the group exposed to cigarette smoke (23.26 ng/ml) were higher than those in the group that received a combination of ethanol extracts of gumitir and Jepun flower (15.56 ng/ml). The treatment groups that received the ethanol extract of gumitir (Tagetes erecta) and Jepun (Plumeria alba) flowers had lower testosterone levels (15.56 ng/ml) than the control group (19.95 ng/ml), but there were no statistically significant differences.

|

4. Discussion

- Chronic exposure to cigarette smoke has been shown to significantly reduce testosterone levels in rats. Cigarette smoke induces oxidative stress and inflammation in the testicles, which leads to decreased sperm count, increased sperm deformity, and histopathological damage [7]. Testosterone reduction is associated with increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which damage testicular tissue [7].Nicotine is a major psychoactive component in tobacco that can trigger oxidative stress and is a specific molecular inhibitor of the testosterone synthesis process. Empirical data suggest that nicotine and its primary metabolite, cotinine, directly inhibit the production of luteinizing hormone (LH) induced testosterone and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in primary Leydig cell cultures. This inhibition process occurs after stimulation by cAMP, which implies that nicotine targets are downstream of adenylate cyclase activation, indicating a disturbance in intracellular signal transduction [8].In contrast to nicotine's mechanism, which focuses on functional inhibition, other components of cigarette smoke, such as Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and heavy metals, damage Leydig cells through transcriptional repression and direct cytotoxicity. PAHs, such as benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), are potent endocrine disruptors contained in cigarette tar.9 Long-term exposure to B[a]P significantly lowers serum and intratesticular testosterone levels by suppressing the expression of key steroidogenic genes, especially StAR and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) [9]. Although the initial triggers of nicotine, PAHs, and heavy metals are different, their toxic effects ultimately converge on two major cellular damage pathways: chronic inflammation and apoptosis. Cigarette smoke is a potent pro-inflammatory stimulus [10]. Its various components, both directly and indirectly, activate the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway [11]. Under the basal State, NF-κB is in an inactive State in the cytoplasm, bound to its inhibitor protein, IκB-α. Pro-inflammatory stimuli trigger phosphorylation and degradation of IκB-α, allowing NF-κB (commonly p65/p50 dimers) to translocate to the nucleus [11]. Inside the nucleus, NF-κB functions as a transcription factor that induces the expression of various pro-inflammatory genes, especially the cytokine Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) [10].The role of TNF-α in this context is crucial, as it serves as a central mediator that translates various toxic signals into integrated suppression of steroidogenesis. TNF-α is not just an inflammatory marker; It is a direct and potent inhibitor of testosterone synthesis. TNF-α has been shown to suppress transcription of key genes, including StAR, P450scc, and P450c17, in Leydig cells [10].Chronic exposure to secondhand smoke has been extensively documented as a trigger for endocrine dysfunction and decreased levels of reproductive hormones, including testosterone [1]. The main pathophysiological mechanism underlying this phenomenon is the induction of oxidative stress, a condition in which there is an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the ability of the body's antioxidant system to neutralize it [1]. Toxic substances contained in cigarette smoke, such as nicotine, cotinin, and benzo(a)pyrene, have mutagenic properties and can directly damage testicular tissue. This exposure targets Leydig cells, which are responsible for testosterone synthesis. These toxic compounds can also interfere with the work of the enzyme adenylyl cyclase which plays an important role in the process of steroidogenesis (steroid synthesis) in Leydig cells. This damage triggers apoptosis (programmed cell death) in Leydig cells and directly interferes with testosterone production [21].Various studies have shown significant decreases in testosterone levels and histological damage to the testicles due to exposure to cigarette smoke [1,21]. One study reported that exposure to cigarette smoke for 30 days significantly reduced the number of Leydig cells and serum testosterone levels in male Wistar rats [22]. Another study noted a significant decrease in testosterone levels (p<0.05) in rats given nicotine over four weeks [21]. The contradiction between these well-documented findings and the results of current research indicates that one of the links in the mechanism of damage from exposure to secondhand smoke may not occur with sufficient intensity. Other sources also note that the severity of cigarette smoke exposure effects is highly dependent on "the patterns of use, type, and number of cigarettes studied", suggesting that the exposure methods in this study may not be adequate.The observed increase in testosterone levels in the cigarette smoke group may be interpreted as an acute compensatory response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Initial exposure to toxins such as nicotine and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) can cause cellular stress in the testicles, triggering negative feedback signals to the hypothalamus and pituitary. This has the potential to induce increased secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) to maintain steroidogenesis homeostasis. This increased LH stimulation, in turn, can spur the still-functional Leydig cells to increase testosterone production temporarily. However, this response is not expected to be sustainable; Further chronic exposure is likely to lead to decompensation, Leydig cell fatigue, and a significant decrease in testosterone levels over time, according to findings in longer-duration studies.Antioxidants have been shown to reduce oxidative stress and protect against testicular damage caused by cigarette smoke. For example, resveratrol and ellagic acid have shown protective effects on testicular tissue and hormone levels in rats exposed to nicotine [12] [13]. Purple sweet potato extract, which contains anthocyanins, has been shown to increase androgen receptor expression in rats exposed to cigarette smoke, suggesting a possible mechanism for maintaining testosterone levels [14] [15].Flavonoids, a major group of polyphenols, have shown potential to regulate androgen levels and improve androgen-related disorders. They interfere with the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, the synthesis and metabolism of androgens, and the binding of androgens to their receptors [16]. Flavonoids such as quercetin are well known for their antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties, which can affect testosterone levels [17].Methanol extract of Vincetoxicum arnottianum, rich in polyphenols, restored altered testosterone levels in BPA-induced testicular toxicity in rats [18]. Similarly, a polyphenol-rich diet containing phloridzin prevents ovarian-induced bone loss and maintains testosterone levels in inflammatory conditions. The presence of tannins in Massularia acuminata root extract increases serum testosterone levels and enhances sexual behavior in male rats, demonstrating their role in maintaining hormonal balance [19].Flavonoids such as luteolin, quercetin, and resveratrol have been reported to increase testosterone production by increasing the expression of the StAR gene in Leydig cells, which facilitates the entry of cholesterol, a precursor to androgen biosynthesis, into the mitochondria [20].Gumitir (Tagetes erecta) and Jepun (Plumeria alba) flower extracts have traditionally been used because they are rich in bioactive compounds. Gumitir flower extract has been reported to contain secondary metabolites, including flavonoids, polyphenols, alkaloids, saponins, tannins, and steroids.6 These compounds are known to have very strong antioxidant activity, as demonstrated by the IC50 value of 17.08 ppm in Tagetes erecta leaf extract, indicating a strong ability to neutralize free radicals. Similarly, Jepun flowers (Plumeria alba) also contain flavonoids, polyphenols, alkaloids, and terpenoids that have antioxidant activity. Theoretically, these antioxidant compounds should be able to counteract the oxidative stress effects caused by cigarette smoke and protect Leydig cells from damage. However, although this extract exhibits strong antioxidant activity in vitro, this activity does not automatically guarantee therapeutic effects in vivo. Factors such as bioavailability (how much of the compound is absorbed by the body), liver metabolism, and the compound's ability to reach and accumulate in target tissues, such as the testicles are decisive. These non-significant results may indicate that, although the extract has potential, its active compounds may not reach Leydig cells in sufficient concentrations to provide a measurable protective effect.This study used a combination of extracts from two plants: gumitir flowers and Jepun flowers. Although the initial hypothesis is that there are synergistic or additive effects, the world of phytopharmacology is complex, with interactions between compounds that can be synergistic (mutually reinforcing), additive (the total effect equals the sum of the individual effects), or even antagonistic (mutually inhibiting). A study examining a combination of extracts from Basella alba and Hibiscus macranthus provides a perfect example of this complexity [23]. The study found that Basella alba extract significantly increased testosterone production, while Hibiscus macranthus extract showed an inhibitory effect at higher concentrations [23]. Although the combination of the two is traditionally used and shows positive effects, this highlights the risk of antagonistic effects if dosages or comparisons between extracts are not balanced. It is quite possible that certain compounds of the Jepun flower (Plumeria alba) interact negatively or inhibit the antioxidant compounds of the gumitir flower (Tagetes erecta), resulting in an insignificant overall effect. These results suggest that the effectiveness of the combination extract cannot be assumed, and that unexpected interactions may have negated the expected protective effects.Quercetin, the main flavonoid in the extract, has been shown in several studies to increase the expression and activity of promoters of the same genes, namely StAR, Cyp11a1 (P450scc), and 3β-HSD, in Leydig cells [24]. This indicates the existence of a direct restorative mechanism. While PAHs function as transcriptional repressors, quercetin acts as a transcriptional activator for these steroidogenic genes. This provides direct pharmacological antagonism of the endocrine-disrupting effects of PAHs.This leads to a "protect and rebuild" model. Lutein and iridoids protect cells (by suppressing apoptosis and inflammation), while quercetin actively restores their functional capacity (by stimulating the expression of steroidogenic genes). This paradigm shifted from a purely defensive mechanism to a restorative strategy. This model comprehensively describes the efficacy of extracts in counteracting the two main mechanisms of cigarette smoke toxicity: functional blockade by nicotine (by providing more StAR proteins to overcome inhibition) and transcriptional repression by PAHs (by directly restimulating target genes).This non-significant finding, while surprising, is not a single anomaly in the scientific literature. Several other studies have also found no significant effect on hormonal parameters after administration of certain herbal extracts [25]. For example, one study reported that methanol extract showed no significant change in testosterone levels during 60 days of treatment [26]. This confirms that not all natural ingredients rich in antioxidants will automatically affect testosterone levels in vivo under all experimental conditions. The results of this study have important scientific implications. First, it prevents unsubstantiated claims about the effectiveness of this combination extract at the dosage and duration used. Second, it serves as a starting point for more rigorous research in the future. Although the current results are insignificant, this study provides an essential foundation, identifies methodological limitations to be avoided, and encourages more focused exploration to confirm the mechanisms and effectiveness of these phytochemical compounds.

5. Conclusions

- The results showed that in the acute phase, exposure to cigarette smoke caused an increase in the hormone testosterone in rats. The combination of ethanol extracts of Tagetes erecta and Plumeria alba may have androprotective potential against hormonal dysfunction caused by cigarette smoke, but does not provide a significant preventive effect on decreased testosterone levels in the subacute phase. Further research of longer duration is needed to assess the preventive effects of extracts on testosterone levels.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author would like to thank the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at Warmadewa University and all parties who have provided support for this research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML