-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Basic Sciences of Medicine

p-ISSN: 2167-7344 e-ISSN: 2167-7352

2021; 10(1): 10-18

doi:10.5923/j.medicine.20211001.03

Received: Jun. 21, 2021; Accepted: Jul. 3, 2021; Published: Jul. 15, 2021

Will Development of Human Anatomy Revolutionize Medical Education?

Rajani Singh1, DG Jones2, Raj Kumar3, Naresh Chandra4

1Department of Anatomy Uttar Pradesh University of Medical Science Saifai Etawah, UP, India

2Department of Anatomy Otago University, Otago, New Zealand

3Department of Neurosurgery, Uttar Pradesh University of Medical Science Saifai, Etawah, UP, India

4Department of Anatomy Hind Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, India

Correspondence to: Rajani Singh, Department of Anatomy Uttar Pradesh University of Medical Science Saifai Etawah, UP, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Vanishing of cadaveric dissection, pruning of the curriculum and teaching schedule, the deployment of unqualified tutors/demonstrators and removal of experienced faculties with closing of Anatomy departments has eroded medical education. So tomorrows’ doctors accumulate deficient Anatomical knowledge impeding successful clinical practice. The objective of this study is to evolve a new model of Anatomy as a subject to deliver adequate Anatomy to improve clinical practice. The literature was reviewed regarding falling standards of the knowledge of Anatomy and growing failure cases. This resulted in a model for the development of Anatomy as a subject by standardizing the curriculum to be taught by medically qualified and experienced staff with the ability for standalone and collaborative research. The model will allow interaction of anatomists with clinicians/trainees by providing instant anatomical solutions during medical education. The well guided cadaveric dissection by experienced faculty will also improve the clinical practice. The model will also generate ready-made records containing variations corresponding to relevant clinical complications helping clinical trainees during clinical practice. This model will provide sufficient knowledge of Anatomy, reservoir of competent anatomical faculty and also revolutionize clinical skills among medical trainees. The aim is to ensure that the quality of medical education is enhanced.

Keywords: Inadequate anatomical knowledge, Medical education, Development of anatomy, Failure cases, Collaborative research

Cite this paper: Rajani Singh, DG Jones, Raj Kumar, Naresh Chandra, Will Development of Human Anatomy Revolutionize Medical Education?, Basic Sciences of Medicine , Vol. 10 No. 1, 2021, pp. 10-18. doi: 10.5923/j.medicine.20211001.03.

1. Introduction

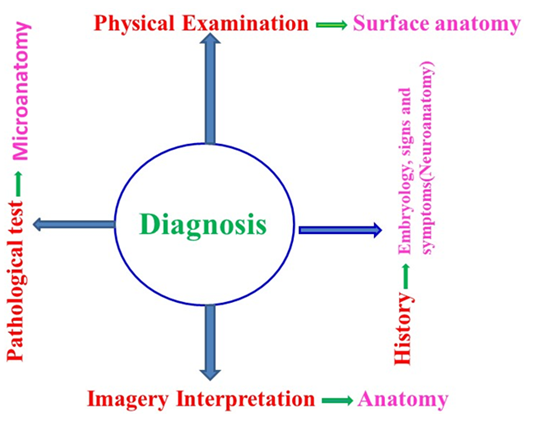

- The diseases are caused by changes in environmental conditions, pathogens, toxins, trauma and misuse of limbs. The results include anatomical distortions in shape, size, location and orientation of structures as well as developmental deficits that impair activities and/or the functioning of macro/microstructures, organs, limbs and bodily systems. The generation of signs and symptoms of discomforts are governed by the brain. The preliminary diagnosis starts from physical examination through observation, palpation, percussion and auscultation involving surface Anatomy (Figure-1) [1] to assess preliminary signs and symptoms of disease.

| Figure 1. Showing importance of anatomy in diagnosis of diseases |

2. Material and Methods

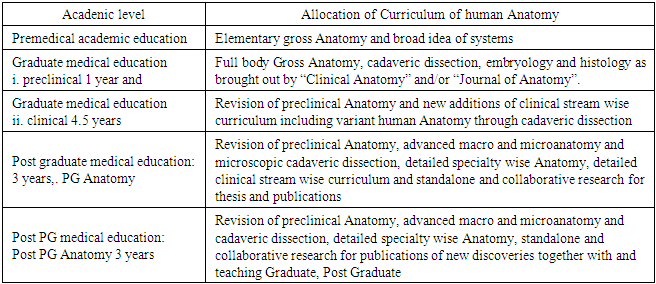

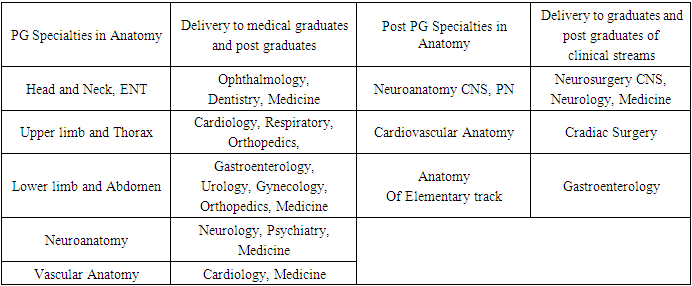

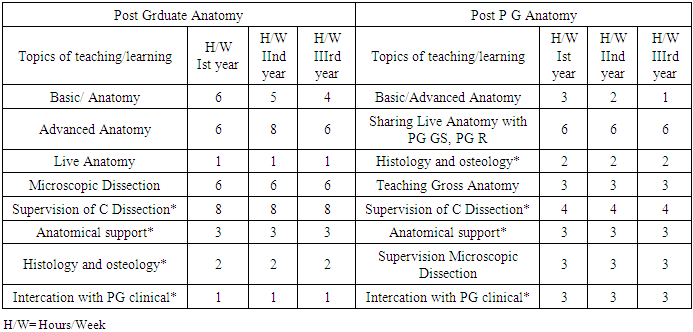

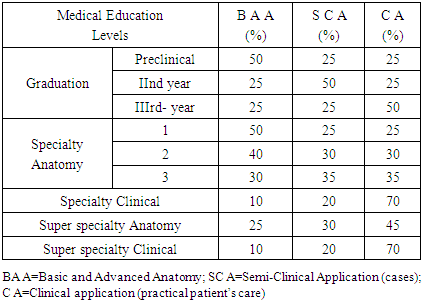

- The review of literature concentrated on what the authors perceive is the inadequate knowledge of anatomy among medical graduates. Questions posed were: ‘why do trainees know too little Anatomy?’, what is the effect of the closure of anatomy departments in some countries? How does dependence upon prosections, models and charts compare with cadaveric dissection’, what parts of anatomy appear to be is irrelevant and redundant? What have been the effect of pruning syllabus of Anatomy?, ‘can clinical diagnosis and treatment be planned with inadequate anatomical knowledge?’ The search for clinical handicaps due to ignoring and neglecting the Anatomy was also done. The databases used were Researchgate, Wiley’s on line library, Google scholar, Medline, Scielo and Pubmed. Only English language articles were selected.Scheme of Development of Human AnatomyThe development model of Anatomy will be formulated as under at Graduation, Post Graduation (PG/specialty) and Post PG (Super specialty) academic levels. The systematic development of human Anatomy will start from delivery / acquisition of balanced blend of basic and applied Anatomy sufficient to comprehend the skill and knowledge of therapeutic modalities in clinical practice. Development of Human Anatomy during graduation will be done at preclinical and at clinical training.Preclinical AnatomyThe minimum necessary workable clinically oriented syllabus should be allocated in preclinical medical graduation brought out by the journals, Clinical Anatomy and Journal of Anatomy as detailed by Kumar and Singh, 2020 in their Model of Pedagogy with minor reorganization. Later on, the syllabus may be standardized to consist of surface Anatomy, the systems and basic concepts of structures and organs (shape size, location, configuration and landmarks). Developmental and embryological principles are to be outlined with reference to congenital defects plus organization of micro-elements in these structures. The curriculum should consist of analysis of normal histological slides/radiological images of various macro/microstructures [16] and their verification through cadaveric dissection to be applied in clinical complexities encountered during undergraduate clinical training (Table 1).

|

|

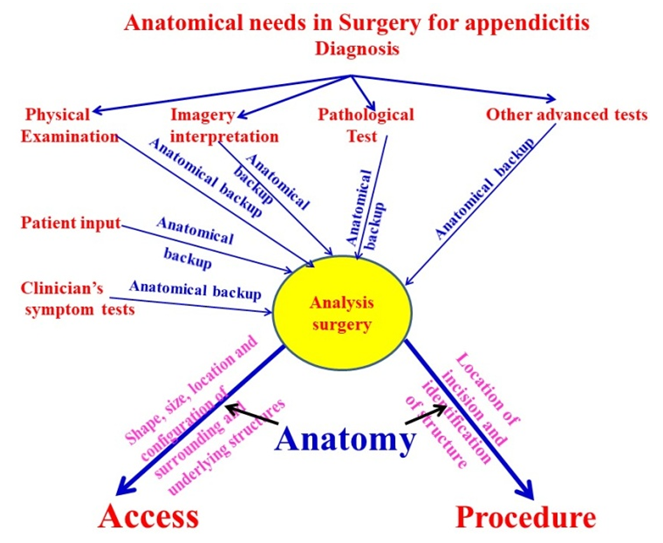

| Figure 2. Showing how anatomy is indispensable for surgery e.g. in appendicitis |

|

|

3. Results and Discussion

- Our analysis of this model and the available literature found that the deficiencies producing inadequate knowledge of Anatomy can be eliminated and the quality of clinical practice refined. “There is a general feeling among junior students that Anatomy is boring associated with memorizing vast amounts of factual knowledge (Vast and rote)” “Anatomy is perceived as learning the names of structures” “Well, Anatomy is just to crame. There is nothing to understand about anatomy (student 3b, year 3)” [3]. These factors creating disinterest in Anatomy among students can be eliminated by reorganizing, redistributing and standardizing the curriculum. This has been done by teaching Anatomy through repeating topics by lectures, demonstration classes, dissection and interaction and exposure to clinical cases together with providing continuous and consistent anatomical solutions to problem based learning. In this way, the material is retained, and fresh motivation can be kindled among students as long as the classes are taught in a coherent manner by medically qualified and well experienced faculty.A standardized/reorganized curriculum at various stages of medical education will eliminate widely variable curriculum of Anatomy and this will facilitate migration of students across various countries, American and British medical schools in particular [18,35]. The variations in curricula are currently so great that the anatomical knowledge acquired by medical students, even within the same country incompatible. The variability across countries is far greater, so that the acquired knowledge and expertise in clinical practice leads to the difficulties experienced by migrating students.The provision of competent faculty in this model will not only provide easily comprehensible anatomical knowledge through amalgamation of best and thoughtful teaching methodology but also facilitate the advancing knowledge of anatomy needed to combat any future threats of grey areas in diagnosis and treatment. Interdisciplinary collaborative research by medically qualified, expert and experienced anatomical faculties will enhance the quality of medical education by explaining difficult to comprehend clinical grey areas. These include variations in macro/microstructures for safe clinical practice supported by anatomical analysis and solutions to the diagnosis of disease and treatment at all levels of medical education. This morphological research will be used to help formulate drugs to efficiently control the antigens and protect against from complications due to drug reactions. The amalgamation of research on variant structures, their fascicular constituents, pathways, distribution of nerve fibers and their configuration and identification for neuro-microsurgery at fascicular level will add another dimension to medical practice [2,33]. Knowledge like this may prove useful when confronted by epidemics due to new pathogens or antigens like Corona/Ebola viruses. While advances in all cognate fields are required when confronted by situations such as these, anatomically-based clinical advances may contribute substantially to the clinicians’ armamentarium, and thus decrease mortality and morbidity. For surgeons the availability of precise and well informed anatomical background, and the ability to practice extensively on cadavers will tremendously enhance the confidence of the novice surgeon and enhance the precision of surgery with minimal damage to surrounding structures.This will not only improve clinical practice but also produce semi-clinical anatomists to teach Anatomy teaching more in context with clinical problems. The model will facilitate meeting the future challenges of medical education and synergize the practical and theoretical interaction between clinical and non-clinical faculty and students. Thus the scheme will develop not merely anatomy academics to produce future competent faculties for Anatomy but also enhance clinical skills by supplementing anatomical solution by exploring anatomical variations and expanding morbid anatomy to overcome complications of diagnosis and treatment.

4. Conclusions

- This aim of this model of development of Anatomy is to reorganize and standardize the Anatomy curriculum to be taught by qualified and experienced faculties of Anatomy with a strong background in standalone and collaborative research. Its goal is to decrease the rate of failure due to inadequate anatomical knowledge at all levels of medical education and to restore the falling credibility of the medical profession. The graduate, PG and post PG trainees will be exposed to one to one synergistic interaction and cadaveric dissection to help them understand imagery interpretation, disease and surgical access and procedure. In addition, it is intended to assist in helping understand malfunctioning of structures and systems and hence to comprehend molecular interactions of pathogens and antibodies for formulating and administering the drugs. In this way the development of Anatomy will contribute to improve clinical health care of human beings.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML