-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Basic Sciences of Medicine

p-ISSN: 2167-7344 e-ISSN: 2167-7352

2019; 8(1): 12-17

doi:10.5923/j.medicine.20190801.02

Cervical Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (CIN) among Young Women in Jos Metropolis, Nigeria

James Akpenpuun Ikyernum1, Ayu Agbecha2

1Department of Medical and Andrology Laboratory, First Fertility Hospital, Makurdi, Nigeria

2Department of Chemical Pathology, Federal Medical Centre, Makurdi, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ayu Agbecha, Department of Chemical Pathology, Federal Medical Centre, Makurdi, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is a premalignant lesion of the cervix that progresses into cervical cancer if untreated. An early diagnosis which determines the treatment of CIN is a preventive measure of cervical cancer. Diagnosis in a developing setting like Nigeria lacks screening programmes which may affect early detection of the disease. Aim: the study aimed at determining the prevalence of CIN and the pattern of cytological abnormality in young women in Jos, Nigeria. Methods: the cross-sectional study involved 200 women aged 15-45 years. A cervical smear was obtained from these women and the cytological features determined using the Papanicolaou method. The cytological features were grouped into Normal smears, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), low grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LGSIL), high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL). Frequencies were determined and their prevalence rates calculated. Results: the overall prevalence of CIN was 61/200(30.5%) and the pattern of cytological abnormality were ASC-US 28/200(14%), LGSIL 31/200(15.5%), HGSIL 30/200(15%). The age group with the highest CIN prevalence was 40-45 years (11.5%). Conclusion: the prevalence of CIN is high and a need for regular cervical screening programme to identify and monitor women with premalignant lesions for the purpose of early treatment.

Keywords: Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, High grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

Cite this paper: James Akpenpuun Ikyernum, Ayu Agbecha, Cervical Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (CIN) among Young Women in Jos Metropolis, Nigeria, Basic Sciences of Medicine , Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 12-17. doi: 10.5923/j.medicine.20190801.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

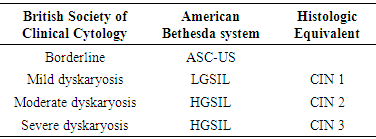

- Cervical cancer is reported the 4th most common cancer among women worldwide [1]. Global estimates in the year 2012 show 527,624 new cases and 265,672 deaths, while Nigerian estimates stood at about 14,089 new cervical cancer cases and 8240 deaths [2]. This report further states that cervical cancer is the 2nd leading cause of female cancer as well as female cancer-related deaths in Nigeria. In the last fifty years, the morbidity and mortality of cervical cancer have drastically reduced in the developed countries because of effective screening programmes [3]. This is in contrast to developing nations where limited or unavailable screening programmes hamper cytological testing [3].Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is a premalignant precursor of cervical cancer also referred to as squamous intraepithelial lesions formerly called cervical dysplasia. These terms are used interchangeably and describe the histologic changes on the uterine cervix. CIN in sub-Saharan Africa is facilitated by biological, socio-cultural and socio-economic factors [4]. Approximately 90% of CIN cases and over 99% of cervical cancer cases occur in HPV-positive patients [5]. The most important risk factor for cervical cancer development is chronic persistent HPV infection due to compromised immunity [4]. Women with HIV are more likely to have persistent HPV infection leading to cervical abnormalities and cancer [6]. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) other than HPV also contribute to cervical neoplasia. Polygamy, early age at first sexual intercourse, high parity, multiple male sexual partners are among the socio-cultural/economic risk factors of HPV infection and cervical neoplasia in sub-Saharan African [4].The host immune system spontaneously eliminates CIN even without intervention and in most cases remains stable, with only a few percentages progressing to cervical squamous cell carcinoma [7]. The progression from normal, through cervical intraepithelial lesions to cervical cancer, is evident in the form of cytopathic effects of variable differentiation that is detectable through cytological examination. Cervical intra-epithelial lesions are characterized by abnormal cellular proliferation, maturation, and atypia with conspicuous nuclear abnormalities including hyperchromasia, pleomorphism, irregular borders, and abnormal chromatin distribution [8]. Currently, two systems of cytology reporting are commonly used; the British Society for Clinical Cytology [9], and the revised American Bethesda System 2001 [10]. These systems are comparable to the histologic equivalent [11]. (table 1), The revised Bethesda System is the most widely used, due to its uniform and well-defined diagnostic terminology that facilitates unambiguous communication between the laboratory and the clinician [12]. The revised system divided the premalignant squamous lesions into three categories (table 1)i. Atypical squamous intraepithelial cells (ASC)ii. Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LGSIL)iii. High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL)

|

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

- The cross-sectional study examined the cervical smears of women and determined the frequency of those with normal and abnormal cytology as well as the pattern of abnormality.

2.2. Study Area

- The study was conducted at the Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH), Nigeria. The hospital is located in Jos, the capital of Plateau state; one of the oldest commercial cities in north-central Nigeria. The hospital renders tertiary health care services to the populace of the entire region. The populace is comprised mainly of the Beroms and about over forty ethnolinguistic indigenous groups. People from other parts of the country have come to settle in Plateau State; these include the Igbo, Yoruba, Hausa, and Fulani. These ethnic groups are predominantly farmers and have similar cultural and traditional ways of life.

2.3. Selection of Participants

- After obtaining institutional ethical clearance, a total of 200 women aged 15-45 years were randomly selected from a population of women seeking cervical screening at JUTH.

2.4. Sample Collection

- After collection of bio-data information from the participants, the collection of swab sample followed. A vaginal speculum was passed to visualize the cervix. A sterile endocervical brush was used to swab materials from the endocervix. The cellular materials from the endocervical brush were rapidly spread on grease free glass slides in three replicates and were fixed in 95% acetone in a Coplin jar before staining. The smears were stained using standard Papanicolaou's method.

2.5. Laboratory Methods

2.5.1. Papanicolaus Staining Method

- The fixed smears were taken through descending grades of alcohol (80%, 70%, 60%) and down to water for three minutes. The smears were stained in Harris haematoxylin for three minutes. Smears were rinsed in tap water for one minute and were differentiated in 1% acid alcohol for 3 seconds. The smears were further rinsed in tap water for 2 minutes and blued in ammoniated water for 1 minute. The stained smears were rinsed in tap water for 3 minutes and dehydrated in 70% and 95% alcohol for 2 minutes respectively. Smears were stained in orange G6 for 1 minute and treated with two changes of 95% alcohol for 1 minute each. They were stained in eosin azure 50 solutions for 2 minutes and treated in 3 changes of absolute alcohol for 1 minute each. They were treated with xylene for 2 minutes and again cleared in 2 changes of xylene for another 2 minutes. The slides were mounted using DPX and examined at x40 objective using the light microscope. Changes in the squamous cells of the cervix were graded according to their cytological features.

2.5.2. Cytological Gradings

- a. Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significanceRefers to inflammatory, reactive and reparative processes which are atypical and of higher level and insufficient to be classified as CIN.This term is used when1. There is genuine doubt as to whether or not a smear is abnormal. 2. The nuclear changes of the cells are not typical and convincing of cervical neoplasia and as such cannot be labeled as negative. 3. Human papillomavirus changes are seen on the smear, without neoplasia. 4. Severe inflammatory changes exist on the smear, which can sometimes appear almost neoplastic. 5. Interpretation of the smear is difficult due to poor handling, fixing and staining process (such as due to air drying).b. Low-grade squamous intra-epithelia neoplasia or CIN IThe LGSIL includes cytological changes consistent with HPV changes called koilocytotic atypia. Koilocytes have a large cytoplasmic vacuole surrounding the nucleus and the nucleus being abnormally large and dark with the cytoplasm condensed. The term is used when1. The nucleus is occupying up to 1/2 of the area of the cell (Nucleocytoplasmic ratio of half)c. High-grade squamous intra-epithelia neoplasia or CIN II/IIIThe HGSIL is characterized by more severe abnormalities in the size and shape of cervical squamous cells and is more likely to progress to cancer. The term is used when1. The nucleocytoplasmic ratio is more than ½ and greater than 2/32. The chromatin pattern is usually more abnormal compared to LGSIL3. The nucleus may have a bizarre shape.d. Carcinoma-in-situThe term is used when1. Bizarre nuclear changes and keratinization are observed.

2.6. Statistical Methods

- Frequencies were determined according to normal and abnormal smears as well as age groups. Percentages were calculated and the prevalence’s of CIN reported.

3. Results

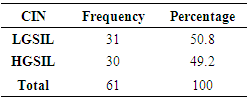

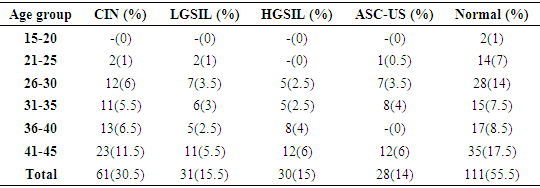

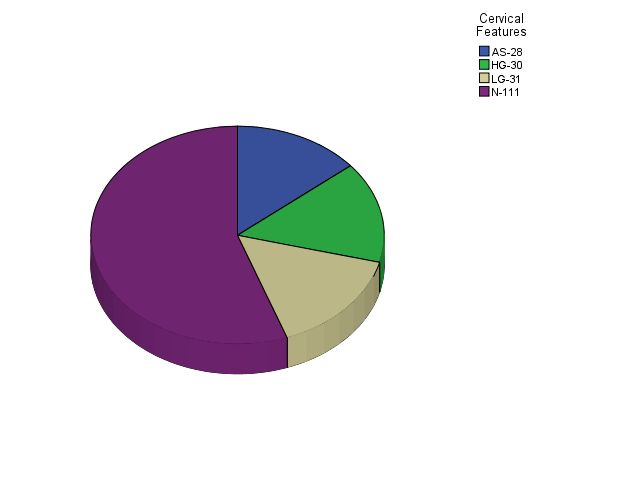

- Figure 1 shows the prevalence of cervical abnormalities in women studied. Out of the 200 women that participated in the study, 28 of them were diagnosed of ASC-US, 31 presented with LGSIL, 30 were found to have HGSIL while women without any neoplastic lesions stood at 111. The overall prevalence of LGSIL was 15.5% (31/200), HGSIL 15% (30/200), ASC-US 14% (28/200). The distribution pattern of CIN in women is presented in table 2. Out of the 30.5% (61/200) women that presented with CIN, 31 had LGSIL while 30 showed HGSIL. The prevalence of LGSIL was 50.8% (31/61) and HGSIL 49.2% (30/61). The age distribution of CIN in women is presented in table 3. The 200 women involved in the study were grouped according to their age grade 41-45, 36-40, 31-35, 26-30, 21-25 and the prevalence of CIN respectively stood at 11.5% (23/200), 6.5% (13/200), 5.5% (11/200), 6% (12/200), 1% (2/200).

|

|

| Figure 1. The prevalence of cervical abnormalities in women |

4. Discussion

- Cancer of the cervix affects women during the most productive years of their lives, leading to a negative impact on their lives [13]. CIN as a premalignant precursor of cervical cancer, need to be identified early and treated to prevent its development into cervical cancer. However, cytology-based screening, which is used in developed countries, is resource intensive, and difficult to realize in very many countries in sub-Saharan Africa because of poor healthcare infrastructure and lack of resources. In this present study, efforts were made to determine the prevalence rate of CIN among young women using a cytological screening method.The present study shows a CIN prevalence of 61/200 (30.5%) in the women studied. This finding shows a higher prevalence than 15.7% (Jalingo), 16.2% (Benin), 13.9% (Ibadan), 14% (Zaria), 14.4% (Ile-Ife) observed in other previous studies conducted in Nigerian women [14-18]. Njagi et al, observed 15% (54/350) CIN in Kenyan women [19]. Similar high prevalence’s comparable with the present study were observed in Nigerian (26.9%) and Bulgarian (24%) women [20, 21]. The high prevalence of CIN observed in the present study may be due to the nature of the sample population. The study comprised of women presenting for cervical cancer screening with many of them probably being referred by a healthcare worker following complaints of symptoms suggestive of either genital tract infection or cervical cancer. Hence, they were naturally a selected “high risk” group for CIN. Although HIV determination was not carried out in the present study, the high prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS in the study region could have influenced the observed high rate of CIN. Previous studies conducted in Kano, Jos, Maiduguri Nigeria have respectively shown a high prevalence (31.1%, 29.0%, 32.7%) of precancerous lesions of the cervix among HIV infected women [22-24]. Nigeria ranks second in global HIV burden and also high in the global cervical cancer burden [25, 1]. Cervical cancer rates are on the rise, paralleling the HIV epidemic. The observed rise in this rate has been linked to chronic deviations in the immune systems due to HIV Infection [26-28]. Compromised immunity due to HIV/AIDS favor HPV infection persistence which enhances the development of precancerous lesions that precipitates cervical cancer.Although HPV detection was not included in this study, the high rate of CIN observed may be due to HPV infection. It is an established fact that HPV infection is linked to a majority of CIN cases [29]. Besides HPV, other STIs like Herpes simplex type 2, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea have all been associated with an increased risk for CIN and invasive cervical cancer [30]. These infections excite chronic inflammatory response which causes the generation of free radicals, which are thought to play an important role in the generation and progression of cancers [30]. The aforementioned biological risk factors (HIV, HPV, STIs) of cervical neoplasia could be influenced by socio-cultural and economic factors like widespread polygamy, early marriage, high parity, multiple sexual partners in the study region [4]. In this study, some of these predisposing factors like the number of male sexual partners, age at first sexual intercourse, HIV/AIDS status, and STIs were not considered due to some difficulties encountered during sampling. Since most participants would not reveal information considered secret. The present study observed 14% (28/200) ASC-US in the women studied. Bakari et al., Obaseki & Nwafor respectively observed a high rate of 77/250(30.8%), 478/3,284 (14.6%) ASC-US in Nigerian women, comparable with the present findings [31, 15]. The ASC-US diagnosis has caused confusion and controversy with respect to its significance and appropriate use [32] which has led several authors suggesting a frequency value of ASC-US not exceeding 2-3 times the frequency of LGSIL. This suggestion is in line with the present studies observation of an ASC-US frequency value less than LGSIL [33]. Despite the controversy surrounding ASC-US diagnosis, a meta-analysis showed that ASC-US can progress into invasive cervical cancer and precancerous lesions or exist in these lesions at a low rate, while regression occurs in 68.2% [34]. It is reported that out of 1000 women with atypical squamous lesions one already has invasive cervical cancer [35]. During monitoring of women with ASC-US lesions, 10-30% of LGSIL and HGSIL were reportedly diagnosed [36]. In view of these findings, Barcelos’ study of analysis of ASC-US and cytologic criteria, advocates for serious monitoring of patients with ASC-US lesions [37].The overall distribution pattern of CIN in the present study was 15.5% (31/200) LGSIL, 15% (30/200) HGSIL and specific distribution pattern among CIN was 49.18% (30/61) HGSIL, 50.82% (31/61) LGSIL. This specific distribution pattern is similar to 42.9% HGSIL and 57.1% LGSIL found in another Nigerian study [38]. Several studies in Nigeria and other parts of the world reported LGSIL as the commonest premalignant cervical abnormality observed in women studied [39-41]. Contrary to the present finding, Duru et al., found HGSIL as the commonest abnormality among the women studied [42]. LGSIL is a precancerous lesion characterized by a shorter and less observable clinical course, with cell changes associated with HPV. Several studies suggest that LGSIL is mainly caused by low-risk HPV infection, with evidence of high-risk HPV also involved. [43, 44]. While LGSIL may regress spontaneously in a significant number of patients, HGSIL progresses to invasive cancer if left untreated [45]. In this study, the age group with the highest prevalence of CIN was 41-45years followed by 36-40years. Similar to this study, Oguntayo & Samaila in a Nigerian population observed the highest prevalence of CIN in age grade 40-49 years, with a mean age for CIN at 37.6 years [46]. The present finding shows that risk of premalignant changes and consequently cervical cancer increases with age. Women can develop CIN at any age, however, women generally develop it between the ages of 25 to 35 [47]. Age is a risk factor of HPV infection and as such CIN. The start age of sexual intercourse determines the course of HPV or HPV persistence [4].Other than the elimination of certain socio-cultural practices and improvement of socio-economic status in the study region, prevention and control of cervical cancer hinges on early detection of cervical neoplasia. Based on the high prevalence observed in this study, an urgent need for a regular cervical screening programme to identify and monitor women with premalignant lesions for accessibility to early treatment is recommended.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML