-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Basic Sciences of Medicine

p-ISSN: 2167-7344 e-ISSN: 2167-7352

2013; 2(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.medicine.20130201.01

Oral and Urinary Colonisation of Candida Species in HIV/AIDS Patients in Cameroon

Longdoh A. Njunda1, Jules C. N. Assob2, Shey D. Nsagha3, Henri L. F. Kamga1, Ejong C. Ndellejong1, Tebit E. Kwenti1

1Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon

2Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O.Box 63, Buea, Cameroon

3Department of Public Health and Hygiene, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O.Box 63, Buea, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Tebit E. Kwenti, Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

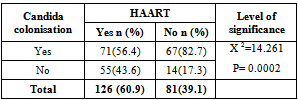

Candidiasis which is one of the most common opportunistic infection in HIV is caused by Candida species that vary with respect to their epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility. This study was designed to determine the distribution and antifungal susceptibility pattern in HIV patients in Cameroon. Oropharyngeal and urine specimens were cultured on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar. Speciation was achieved by the germ tube and sugar assimilation tests, and antifungal sensitivity test was performed using a commercially available test kit. 138 (66.67%) of the 207 participants had candidiasis. Among them, oropharyngeal colonisation 122 (81.2%) was significantly (P = 0.0003) higher than urinary colonisation 26 (18.8%). Candida albicans was the most predominant species isolated. The prevalence of candidiasis was significantly (P = 0.0002) higher among patients who were not on HAART (Highly Active Antiretroviral therapy) (82.7%) than in patients on HAART (56.4%). No significant association was observed between candidiasis and CD4+ T cell count. Most fungal isolates were sensitive to Ketoconazole (85.5%) meanwhile most were resistant to nystatin (68.1%). In conclusion, we reported a very high prevalence of candidiasis in HIV patients in Cameroon and the prevalence tended to decrease in individuals on HAART. Ketoconazole was observed to be the most sensitive antifungal agent.

Keywords: Candidiasis, HIV, Prevalence, Antifungal, Susceptibility, Oropharyngeal, Urine, HAART, CD4 + T Cell

Cite this paper: Longdoh A. Njunda, Jules C. N. Assob, Shey D. Nsagha, Henri L. F. Kamga, Ejong C. Ndellejong, Tebit E. Kwenti, Oral and Urinary Colonisation of Candida Species in HIV/AIDS Patients in Cameroon, Basic Sciences of Medicine , Vol. 2 No. 1, 2013, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.medicine.20130201.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Mucocutaneous candidiasis is one of the most common manifestations of HIV/AIDS worldwide with oropharyngeal candidiasis being the most widely reported[1]. Worldwide, it is estimated that 9.5 million HIV patients suffer from oral candidiasis[2]. Other studies have shown thatapproximately 90% of HIV/AIDS infected persons have at one point demonstrated oropharyngeal colonisation by Candida species[3]. Candida species normally colonise the gastrointestinal tract of healthy individuals and in HIV/AIDS patients. The infection is commonly acquired endogenously except in a few cases where strains can be transmitted from person to person[4]. In the course of HIV infection, patients appear to be colonized with one or more dominant strains which can tend not to change over time[5]. Progressive cell mediated immunodeficiency, with CD4+ T cell counts less than 200cells/µl is a risk factor for colonisation with Candida species and development of Candidiasis[6].Topical or systemic application of antifungal drugs can be used in the treatment of mucocutaneous candidiasis but very often colonisation is not eradicated[5]. Despite the treatment of mucocutaneous candidiasis with oral antifungal agents, increasing evidence shows that prolonged use of these drugs causes resistance to both systemic and topical users[7]. It has been reported that treatment failures have been noticed with azoles, particularly fluconazole used for the treatment of recurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis[8].In Cameroon, a country in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has an HIV prevalence of 5.3%[9], information on the distribution of Candida species in the oral cavity and urine of HIV/AIDS infected population of the country is not readily available. This cross sectional study was therefore designed to determine the rate of Candida species colonisation in the oral cavity and the urine of HIV/AIDS patients as well as to determine the antifungal susceptibility profile of the fungal isolates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

- This hospital-based cross sectional study was conducted from the 14th of February to the 15th of August 2011 on HIV/AIDS patients recruited in the Mutengene Baptist Hospital. The study was approved by the Cameroon Baptist Convention Institutional Review Board (CBC IRB). Patients of both sexes and all age groups whether on HAART or not were eligible for the study. Patients were required to provide a signed informed consent form which was duly explained to them in the local Pidgin English Language and were not to be on any antifungal medication 3months prior to the recruitment of the participants.

2.2. Sample Collection

- Mouth swaps and urine specimens were collected from all participants using sterile cotton wool swabs and wide mouth transparent sterile screw capped containers respectively. Participants were instructed on how to collect mid-stream urine samples.

2.3. Microscopy

- Oropharyngeal swab and centrifuged urine sediment samples were microscopically examined on a clean grease free glass slide using the 10X and 40X objectives for the presence of pus cells and of small, round to oval, thin-walled, clusters of budding yeast cells and branching pseudohyphae characteristically typical of Candida. Smears were made and Gram stained and latter observed at 100X for fungi elements.

2.4. Culture

- Oropharyngeal and urine specimens were cultured on Chloramphenicol impregnated Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) and incubated at 35℃ (± 2°C) for 24-72 hours under aerobic conditions for the observation of colonies which are characteristically white to cream coloured, smooth, glabrous yeast-like in appearance. Colonies were Gram stained and sub-cultured on SDA[10].

2.5. Germ Tube Test

- Single colonies from sub-cultures were incubated in human serum and incubated at 37℃ and after 24 hours, wet mounts were prepared and examined under the microscope for germ tube formation[10].

2.6. Chlamydospore Formation

- All Candida isolates from SDA subcultures were tested for the production of chlamydospores in corn meal agar (CMA) incubated at 25℃. Plates were read after 72 hours and examined under the microscope for the presence of chlamydospores.

2.7. Sugar Assimilation

- The ability of the Candida species to utilize the 12 different sugars (Glucose, Maltose, Sucrose, Lactose, Galactose, Melibiose, Cellobiose, Inositol, Xylose, Raffinose, Trehalose and Dulcitol) present in the commercially available INTEGRAL SYSTEM YEAST Plus (LIOFILCHEM, Italy) was exploited to confirm the identified Candida species isolated after incubating the system aerobically at 36 ± 1℃ for 24 - 48 hours.

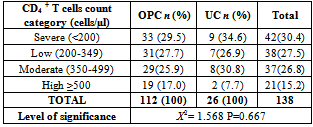

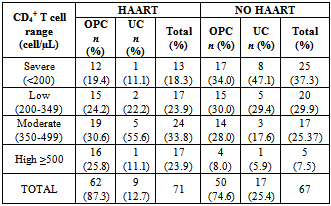

2.8. CD4+ T Cells Counts

- CD4+ T cells counts was determined from study participants using FASCount® and the counts were categorised according to standards of the WHO, as severe when counts <200 cells/µl; low (200–349cells/µl); moderate (350 – 499cells/µl) and high when counts ≥ 500cells/µl[11].

2.9. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

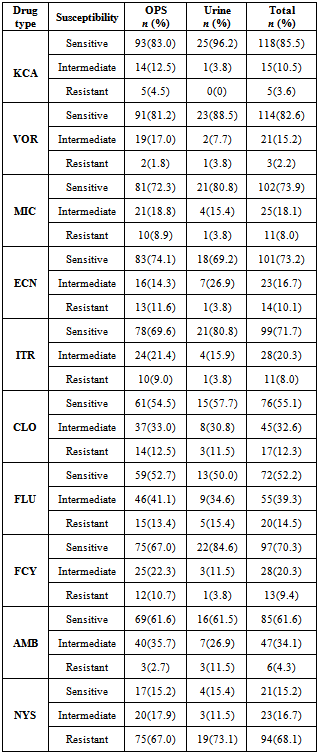

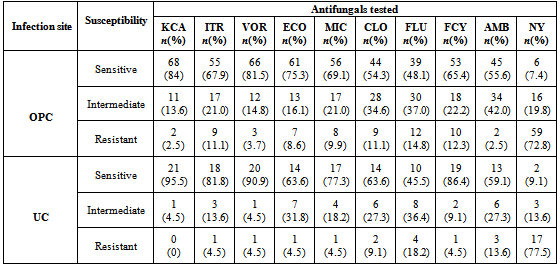

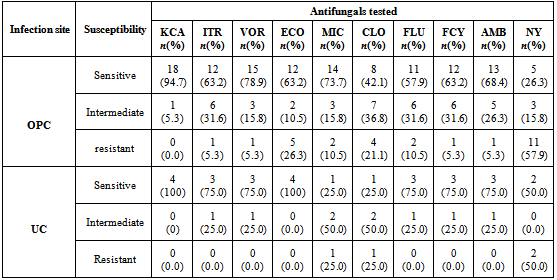

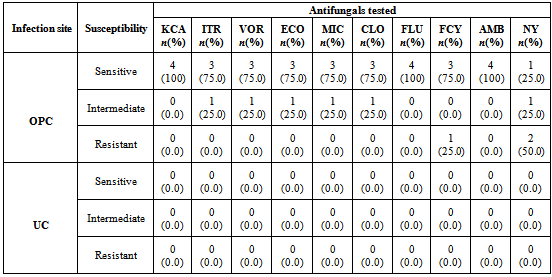

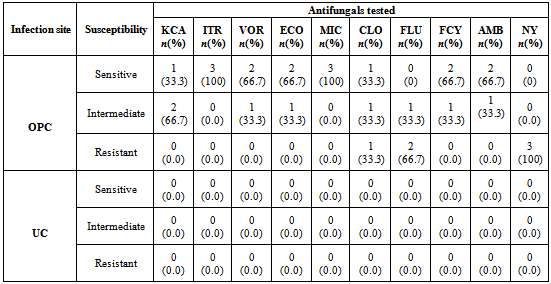

- The in vitro antifungal sensitivity was achieved by testing ten different antifungal agents on all 138 Candida species isolated using the microdilution well method in the commercially available INTEGRAL SYSTEM YEAST Plus (LIOFILCHEM, Italy). This kit is a 24 well system containing culture media and dried antifungals for the identification of 32 clinically important yeasts and sensitivity evaluation to antifungals. Sensitivity is evaluated according to growth or inhibition of yeasts after end point minimum inhibitory concentration for antifungal agent is reached in wells containing media and growth indicator. The in vitro antifungal susceptibility profile for each Candida species was determined by macroscopic observation of colour changes in wells from red (sensitive) to orange (intermediate) to yellow (resistant)Each test consist of a disposable microtitre plate, which contains dried serial dilutions of 10 antifungal agents; amphotericin B (2μg/ml ), nystatin (1.25 μg/ml), fluconazole (64 μg/ml), itraconazole (1 μg/ml), ketoconazole (0.5 μg/ml), 5-fluorocytosine (16 μg/ml), voriconazole (2 μg/ml), econazole (2 μg/ml), miconazole (2 μg/ml) and clotrimazole (1 μg/ml).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

- Analysis was done at a 95% confidence interval using SPSS software Version 14.0. Comparative analysis of the prevalence of Candida species, impact of HAART, and distribution of different Candida species isolated from the oral cavity and urine of HIV/AIDS patients was done using the Chi-square test.

2.11. Limitations

- The population of yeast in the oral cavity is highly complex and patients are often colonised by more than one species or strain. Only Candida was identified to the species level in this study which is not necessarily reflective of the entire population of yeast present. To identify the entire population of yeast will require techniques that are very expensive and will also require experts to perform the analyses and hi-tech facilities which are not readily available in developing countries.

3. Results

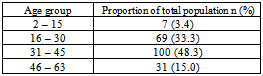

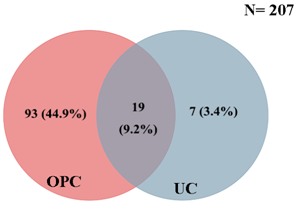

- 207 participants were recruited into the study. 161 (77.8%) were females and 46 (22.2%) were males (Table 1). The participants were between 2-63 years of age (mean age of 36years).

|

| Figure 1. Distribution of candidiasis between the oral cavity and urine of study population |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

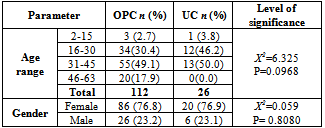

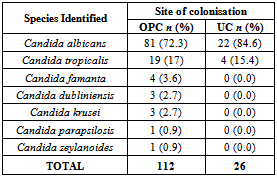

- The overall prevalence of candidiasis among study participants was 66.67%. This result is not very different from the 69.6% reported from a similar study in Italy by Pignato et al.[12]. The prevalence of oropharyngeal colonisation (OPC) in the study population was 54.1%. This result is in line with reports from similar studies in Hong Kong by Tsang and Samaranayake[13], and Taiwan by Hung et al.,[6], where prevalences of 54.8% and 52.4% were recorded respectively. The prevalence of urinary colonisation (UC) in this study was 12.5%. Oropharyngeal Candida carriage was significantly higher than urinary carriage (P = 0.0003), and this could be explained by the fact that Candida is a normal flora of the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract but not in urine. 19 (9.2%) participants had both OPC and UC. The prevalence of OPC and UC was highest among individuals between the ages of 31 – 45 years (49.1% and 50% for OPC and UC respectively). However the difference in the prevalence of OPC and UC with respect to age were not found to be significant statistically (P = 0.0968). OPC was observed more in females (76.8%) than in males (23.2%) in this study. Like OPC, UC was also observed more in females (76.9%) than in males (23.1%). However, the prevalence of candidiasis was not observed to be sex dependent (P = 08080). This could be explained by the fact that the majority of participants in this study were females (77.8%).Candida albicans was the most commonly isolated Candida species from both oropharyngeal and urine samples in this study. 72.3% of Candida albicans was isolated from the oropharyngeal cavity and this result is in conformity with studies carried out in South Africa (78.6%)[14] and Egypt (78.0%)[15]. In urine, Candida albicans recorded a high frequency of 84.6% and this result is similar to that reported by Yongabi et al.,[16] in Yaounde, Cameroon, where Candida albicans was observed to be the most predominant species in urine. Non- albicans species accounted for 27.7% of all Candida isolates from the oral cavity. This result is similar to the 24.0% reported in India by Vaishali et al.,[17]. The possible reasons why Candida albicans constituted a large majority of the Candida species isolated in the oral cavity (72.3%) and urine (84.6) could possibly be due to its wide distribution in nature and its possession of multiple adhesins which gives this pathogen the ability to readily colonise host environment by adhering to host mucocutaneous cells, inert polymers, teeth, and salivary molecules[18]. Despite the fact that non-albicans species are known to have low colonisation potentials, they cannot be ignored because some of these fungi have been associated with pathology as is the case with Candida tropicalis known to be implicated in sepsis associated with bone marrow transplant and oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV/AIDS as well as head and neck cancer patients[19]. Fungaemia due to Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis have been reported in neonates[20]. OPC and UC were observed more frequently in individuals with CD4 T cell count below 200cells/µl. In this study, we failed to observe any significant association between CD4+ T cell count and the rate of infection (P = 0.667). This finding is similar to that earlier reported by Schuman et al.,[21]. The prevalence of candidiasis was higher among patients who were not on HAART (82.7%) than in individuals who were on HAART (56.4%). This difference was observed to be highly significant (P = 0.0002). This finding is consistent with the observation of Omar[22] in Tanzania who reported Candida colonisation to be lower amongst participants on HAART (14.9%) than those not on HAART (38.0%). Among participants on HAART, candidiasis was more prevalent in patients with CD4 T cell counts between 350 – 499 cells/µl, but this difference was not observed to be significant (P = 0.3162), meanwhile among participants not on HAART, candidiasis was significantly ( P = 0.0048) more common in individuals with CD4 T cell count below 200cells/µl. This result indicates that HAART has the tendency to reduce the chances of Candida colonisation amongst HIV/AIDS patients. These findings are in line with the report of Omar[22] in Tanzania. Several studies have validated the positive role of HAART on immune reconstitution amongst which, Nicolatou et al.,[23] in Greece reported a decrease from 58.8% to 37.5% in oral candidiasis amongst HIV/AIDS participants initiated on HAART. Similar trends have been reported in neighbouring Nigeria[24] and in Taiwan[25]. The low prevalence of Candida infection amongst HIV/AIDS individuals on HAART could be explained by the fact that antiretroviral therapy substantially prevents occurrence of Candida infection in HIV/AIDS patients and its efficacy is being largely attributable to the activity of protease inhibitor enzyme on Candida virulence[23].Among all fungal isolates, ketoconazole was found to be the most sensitive antifungal agent (85.5%). This finding agrees closely with that of a similar study in Iran by Parisa et al.,[26]. Other Azoles like miconazole, (73.9%), econazole (73.2%) and itraconazole (71.7%) also recorded good sensitivities’ but clotrimazole (55.1) and fluconazole (52.2%) did not demonstrate appreciable susceptibilities. Flucytosine reported a high sensitivity of 70.3%, similar to results obtained from Nigeria by Nweze and Ogbonnaya[27] where a high sensitivity 80.63% was also recorded.Among the Polyene antifungals, amphotericin B had sensitivity of 61.6% and nystatin 15.2%. These findings are in contrast with reports from Tanzania by Omar[22] who reported 100% susceptibility to both amphotericin B and nystatin among Candida isolates. The possible explanation to this disparity could be due to the fact that the participants in this study were infected with Candida species which are less sensitive to Polyenes. Nystatin resistance in this study was 68.1%, the highest recorded amongst the ten antifungal agents tested. These results differ from previous reports from Iran by Parisa et al.,[26] who documented no resistance to nystatin. The most probable reason for this marked disparity could be related to intrinsic resistance by Candida isolates to nystatin in this study. The national guideline for the management of HIV/AIDS patients actually recommends the use of nystatin as prophylaxis against Candida and other fungi infections[28]. This recommendation was adopted by the Mutengene Baptist Hospital, hence patients were either given nystatin as prophylaxis against fungi infections or it was used in the treatment of Candida infection. The prolonged nature in the management of mucosal candidiasis might have caused the development of drug resistant amongst participants in this study. Furthermore, nystatin resistance could have also arisen from the abusive usage as prophylaxis and auto-medication, because among the ten antifungal agents tested, nystatin is the most accessible in terms of cost and availability, hence can easily be obtained over the counter without prescription, giving room for excessive drug abuse.Among the seven Candida species isolated, Candida albicans recorded a wider range of resistance amongst the ten antifungal drugs tested as compared to the non-albicans species. Meanwhile the non-albicans species were less resistant to azoles compared to Candida albicans isolates. Candida tropicalis being the most frequently isolated non-albicans species reported high resistance to clotrimazole (21.7%) and nystatin (56.5%). Candida famanta had 50% resistance to nystatin while Candida dulbliniensis showed double digit resistance to fluconazole (66.7%) and clotrimazole (33.7). Candida krusei, Candida parapsilosis and Candida zeylanoides had 0.0% resistance to all ten antifungal drugs. These results are in contrast to a similar study in Nigeria by Nweze and Ogbonnaya[27]. The possible reason for this disparity could be the fact that antifungal susceptibilities have been reported to vary with time, geographical location and drug usage, leading to results varying from one study to another[29].

5. Conclusions

- The prevalence of candidiasis among HIV patients in this study was 66.7%, which is very high. Oropharyngeal colonisation was significantly more prevalent than urinary colonisation of candidiasis in this study. The prevalence of candidiasis in this study was not observed to be dependent on the age and sex of the individual. The predominant Candida species was Candida albicans which was isolated with high frequencies in the mouth and urine of these patients. The rate of infection was lower in individuals who were on HAART than in individuals who were not on HAART, suggesting that HAART has a role to play in lowering the rate of colonisation. Ketoconazole reported the highest sensitivity rate against all fungal isolates. The other azoles reported mixed sensitivity and resistance but nystatin was predominantly resistant for all fungal isolates in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study was funded through the departmental research grant of the Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, Cameroon.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML