-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Mechanics and Applications

p-ISSN: 2165-9281 e-ISSN: 2165-9303

2012; 2(2): 14-23

doi:10.5923/j.mechanics.20120202.04

Ionizing Cylindrical Shock Waves in a Rotating Homogeneous Non-ideal Gas

J. P. Vishwakarma, Mahendra Singh

Dept. of Mathematics and Statistics, D.D.U. Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur, 273009, India

Correspondence to: J. P. Vishwakarma, Dept. of Mathematics and Statistics, D.D.U. Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur, 273009, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

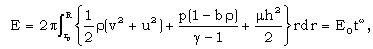

Similarity Solutions are obtained for one-dimensional adiabatic flow behind ionizing cylindrical shock wave propagating in a rotating non-ideal gas in presence of an azimuthal magnetic field. The electrical conductivity in the medium ahead of the shock is assumed to be negligible, which becomes infinitely large after passage of the shock. In order to obtain the similarity solutions, the initial density of the medium is assumed to be constant and the initial angular velocity to be obeying a power law and to be decreasing as the distance from the axis increases. The effects of an increase in the value of the index for variation of angular velocity of the ambient medium, in the value of the parameter of the non-idealness of the gas and in the strength of the ambient magnetic field on the shock propagation are investigated. It is observed that the non-idealness of the gas has decaying effect on the shock wave.

Keywords: Ionizing shock wave, Azimuthal magnetic field, Non-ideal gas, Rotating medium, Adiabatic flow, Similarity solutions

Cite this paper: J. P. Vishwakarma, Mahendra Singh, Ionizing Cylindrical Shock Waves in a Rotating Homogeneous Non-ideal Gas, International Journal of Mechanics and Applications, Vol. 2 No. 2, 2012, pp. 14-23. doi: 10.5923/j.mechanics.20120202.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The formulation of self-similar problems and examples describing the adiabatic motion of non-rotating gas models of stars, are considered by Sedov[1], Zel’dovich and Raizer[2], Lee and Chen[3] and Summers[4]. Rotation of the stars significantly affects the process taking place in their outer layers. Therefore, question connected with the explosions in the rotating gas atmospheres are of definite astrophysical interest. Chaturani[5] studied the propagation of cylindrical shock waves through a gas having solid body rotation and obtained the solutions by a similarity method adopted by Sakurai[6]. Nath, Ojha and Takhar[7] obtained the similarity solutions for the flow behind spherical shock waves propagating in a non-uniform rotating interplanetary atmosphere with increasing energy. Ganguly and Jana[8] studied a theoretical model of propagation of strong spherical shock waves in a self-gravitating atmosphere with radiation flux in presence of a magnetic field. They, also considered the medium behind the shock to be rotating, but neglected the rotation of the undisturbed medium. In all of the works, mentioned above, the medium is taken to be a gas satisfying the equation of state of a perfect gas. Because of high pressure and density that generally occur behind a shock wave, produced by an explosion, the assumption that the gas is ideal is no more valid. The popular alternative to the ideal gas is a simplified van der Waals model. Roberts and Wu[9, 10] adopted this model to discuss the shock wave theory of Sonoluminescence. Vishwakarma et al.[11] too adopted this as their model of a non-ideal gas to obtain the self-similar solutions for the flow behind a magnetogasdynamic cylindrical shock wave propagating in a rotating gas in presence of an azimuthal magneting field. They have taken the electrical conductivity of the initial medium and the medium behind the shock to be infinite. But, in many practical cases the medium may be of low conductivity which becomes highly conducting due to passage of a strong shock. Such a shock wave is called a gas-ionizing shock or, simply ionizing shock. The propagation of a ionizing shock has been studied by Greenspan[12,] Greifinger and Cole[13], Christer[14], Rangarao andRamana[15] and Singh[16] in a non-rotating perfect gas. In the present work, we have extended the work of Vishwakarma et al.[11] by investigating the propagation of gas-ionizing shock in a non-ideal rotating gas in place of magnetogasdynamic shock. In order to obtain similarity solutions, the initial density of the medium is assumed to be constant and the initial angular velocity of rotation to be obeying a power law and to be decreasing as the distance from the axis increases. It is expected that such an angular velocity may occur in the atmospheres of rotating stars.Effects of a change in the strength of ambient magnetic field, in the non-idealness of the gas and in the index of variation of angular velocity of the ambient medium (or index of variation of ambient magnetic field) are investigated. A comparison is also made between the results of the present work and those of the corresponding magnetogasdynamic shocks.

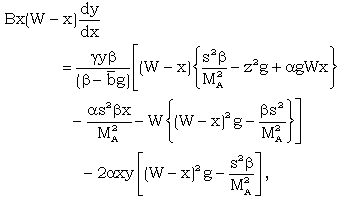

2. Basic Equations and Boundary Conditions

- The fundamental equations governing the unsteady adiabatic cylindrically symmetric motion of a non-ideal and perfectly conducting gas, which is rotating about the axis of symmetry and in which an azimuthal magnetic field is permeated and heat conduction and viscous stress are negligible (c.f. Whitham[17], Chaturani[5]), are:

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

| (2.3) |

| (2.4) |

| (2.5) |

and

and  are the density, pressure and azimuthal magnetic field, respectively, u and v are the radial and azimuthal components of the fluid velocity,

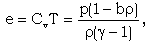

are the density, pressure and azimuthal magnetic field, respectively, u and v are the radial and azimuthal components of the fluid velocity,  is the magnetic permeability, r and t are the distance and time, and e is the internal energy per unit mass. Also, we have

is the magnetic permeability, r and t are the distance and time, and e is the internal energy per unit mass. Also, we have | (2.6) |

| (2.7) |

| (2.8) |

is the gas constant,

is the gas constant,  is the specific heat at constant volume and

is the specific heat at constant volume and  is the ratio of specific heats. The constant b is the ‘van der Waals excluded volume’; it places a limit,

is the ratio of specific heats. The constant b is the ‘van der Waals excluded volume’; it places a limit,  on the density of the gas. We assume that a cylindrical shock is propagating outwards from the axis of symmetry in a rotating non-ideal gas with constant initial density and negligible electrical conductivity in presence of an azimuthal magnetic field. Due to passage of the shock, the gas is highly ionized and its electrical conductivity becomes infinitely large. The conditions across such a gas-ionizing shock are (c.f. Singh and Srivastava[18] and Vishwakarma and Pandey[19])

on the density of the gas. We assume that a cylindrical shock is propagating outwards from the axis of symmetry in a rotating non-ideal gas with constant initial density and negligible electrical conductivity in presence of an azimuthal magnetic field. Due to passage of the shock, the gas is highly ionized and its electrical conductivity becomes infinitely large. The conditions across such a gas-ionizing shock are (c.f. Singh and Srivastava[18] and Vishwakarma and Pandey[19]) | (2.9) |

| (2.10) |

| (2.11) |

| (2.12) |

| (2.13) |

| (2.14) |

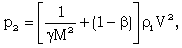

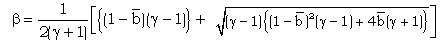

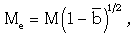

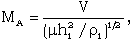

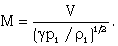

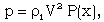

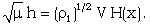

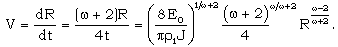

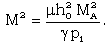

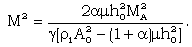

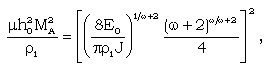

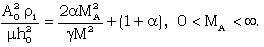

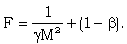

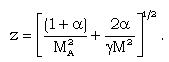

is the parameter of non-idealness of the gas. Here V is the shock velocity,M is the shock-Mach number referred to frozen speed of sound

is the parameter of non-idealness of the gas. Here V is the shock velocity,M is the shock-Mach number referred to frozen speed of sound  , and

, and  is the Alfven-Mach number. Quantities with suffices ‘1’ and ‘2’ correspond to their values just ahead and just behind the shock, respectively. The shock-Mach number

is the Alfven-Mach number. Quantities with suffices ‘1’ and ‘2’ correspond to their values just ahead and just behind the shock, respectively. The shock-Mach number  referred to the speed of sound in non-ideal gas

referred to the speed of sound in non-ideal gas  and the Alfven-Mach number

and the Alfven-Mach number  are given by

are given by | (2.15) |

| (2.16) |

| (2.17) |

| (2.18) |

are constants, and R is the shock radius.In order to obtain the similarity solutions it is assumed that the initial angular velocity

are constants, and R is the shock radius.In order to obtain the similarity solutions it is assumed that the initial angular velocity  varies as

varies as  | (2.19) |

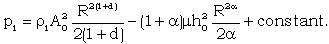

and d are constants.The momentum equation (2.2) in the undisturbed state of the gas, gives

and d are constants.The momentum equation (2.2) in the undisturbed state of the gas, gives | (2.20) |

| (2.21) |

and

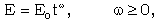

and  are constants. The positive value of

are constants. The positive value of  correspond to the class in which the total energy increases with time. This increase can be achieved by the pressure exerted on the fluid by an expanding surface (a contact surface or a piston). This surface may be, physically, the surface of the stellar corona or the condensed explosives or the diaphragm containing a very high-pressure driver gas. By sudden expansion of the stellar corona or the detonation products or the driver gas into the ambient gas, a shock wave is produced in the ambient gas. The shocked gas is separated from this expanding surface which is a contact discontinuity. This contact surface acts as a ‘piston’ for the shock wave. Thus the flow is headed by a shock front and has an expanding surface as an inner boundary. The situation very much of the same kind may prevail in the formation of cylindrical spark channel from exploding wires. In addition, in the usual cases of spark break down, time dependent energy input is a more realistic assumption than instantaneous energy input (Freeman and Cragges[23]).

correspond to the class in which the total energy increases with time. This increase can be achieved by the pressure exerted on the fluid by an expanding surface (a contact surface or a piston). This surface may be, physically, the surface of the stellar corona or the condensed explosives or the diaphragm containing a very high-pressure driver gas. By sudden expansion of the stellar corona or the detonation products or the driver gas into the ambient gas, a shock wave is produced in the ambient gas. The shocked gas is separated from this expanding surface which is a contact discontinuity. This contact surface acts as a ‘piston’ for the shock wave. Thus the flow is headed by a shock front and has an expanding surface as an inner boundary. The situation very much of the same kind may prevail in the formation of cylindrical spark channel from exploding wires. In addition, in the usual cases of spark break down, time dependent energy input is a more realistic assumption than instantaneous energy input (Freeman and Cragges[23]).3. Similarity Solutions

- Zel’dovich and Raizer[2] shown that the gasdynamic equations admit similarity transformations, that there are possible different flows similar to each other which are derivable from each other by changing the basic scales of length, time, and density. The motion itself may be described by the most general functions of the two variables r and t,

, p(r, t), u(r, t), v(r, t) and h(r, t). These functions also contain the parameters entering the initial and boundary conditions of the problem (and specific heat ratio

, p(r, t), u(r, t), v(r, t) and h(r, t). These functions also contain the parameters entering the initial and boundary conditions of the problem (and specific heat ratio  ).However, there exist motions whose distinguishing property is the similarity in the motion itself. These motions are called self-similar[1, 2]. The distribution as a function of position of any of the flow variables, such as the pressure p, evolves with time in a self-similar motion in such a manner that only the scale of the pressure

).However, there exist motions whose distinguishing property is the similarity in the motion itself. These motions are called self-similar[1, 2]. The distribution as a function of position of any of the flow variables, such as the pressure p, evolves with time in a self-similar motion in such a manner that only the scale of the pressure  and the length scale R(t) of the region included in the motion change, but the shape of the pressure distribution remains unaltered. The p(r) curves corresponding to different time t can be made the same by either expanding or contracting the

and the length scale R(t) of the region included in the motion change, but the shape of the pressure distribution remains unaltered. The p(r) curves corresponding to different time t can be made the same by either expanding or contracting the  and the R scales. The function p(r, t) can be written in the form

and the R scales. The function p(r, t) can be written in the form | (3.1) |

and R depend on time in some manner, and the dimensionless ratio

and R depend on time in some manner, and the dimensionless ratio  is a “universal” (in the sense that it is independent of time) function of the new dimensionless coordinate

is a “universal” (in the sense that it is independent of time) function of the new dimensionless coordinate  . Multiplying the variables

. Multiplying the variables  and x by the scale functions

and x by the scale functions  and R(t), we can obtain from the universal function P(x) the true pressure distribution curve p(r) as a function of position for any time t. The other flow variables, density, velocity and magnetic field are expressed similarly.For self-similar motions the system of partial differential equations (2.1)-(2.5) reduces to a system of ordinary differential equations in new unknown functions of the similarity variable

and R(t), we can obtain from the universal function P(x) the true pressure distribution curve p(r) as a function of position for any time t. The other flow variables, density, velocity and magnetic field are expressed similarly.For self-similar motions the system of partial differential equations (2.1)-(2.5) reduces to a system of ordinary differential equations in new unknown functions of the similarity variable  . Let us derive these equations. To do this we represent the solution of the partial differential equations (2.1)-(2.5) in terms of products of scale functions and the new unknown functions of the similarity variable x,

. Let us derive these equations. To do this we represent the solution of the partial differential equations (2.1)-(2.5) in terms of products of scale functions and the new unknown functions of the similarity variable x, ,

,  .The pressure, density, velocity, magnetic field, and length scales are not all independent of each other. If we have choose R and

.The pressure, density, velocity, magnetic field, and length scales are not all independent of each other. If we have choose R and  as the basic scales, then the quantity

as the basic scales, then the quantity  can serve as the velocity scale,

can serve as the velocity scale,  as the pressure scale, and

as the pressure scale, and  as the magnetic field scale. This does not limit generality of the solution, as the scale is only defined to within a numerical coefficient which can always be included in the new unknown function. We seek a solution of the form

as the magnetic field scale. This does not limit generality of the solution, as the scale is only defined to within a numerical coefficient which can always be included in the new unknown function. We seek a solution of the form | (3.2) |

| (3.3) |

| (3.4) |

| (3.5) |

| (3.6) |

, P, K and H are new dimensionless functions of the similarity variable x, in terms of which the differential equations are to be formulated. The shock front is represented by

, P, K and H are new dimensionless functions of the similarity variable x, in terms of which the differential equations are to be formulated. The shock front is represented by  . The shock conditions (2.9) to (2.13) are transformed into

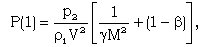

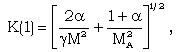

. The shock conditions (2.9) to (2.13) are transformed into | (3.7) |

| (3.8) |

| (3.9) |

| (3.10) |

| (3.11) |

| (3.12) |

| (3.13) |

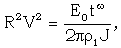

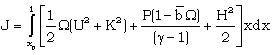

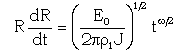

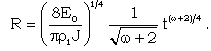

is the radius of inner expanding surface. Applying the similarity transformations (3.2) to (3.6) to the relation (3.13), we find that the motion of the shock front is given by the equation

is the radius of inner expanding surface. Applying the similarity transformations (3.2) to (3.6) to the relation (3.13), we find that the motion of the shock front is given by the equation | (3.14) |

| (3.15) |

is the value of x at the inner expanding surface.Equation (3.14) can be written as

is the value of x at the inner expanding surface.Equation (3.14) can be written as | (3.16) |

| (3.17) |

| (3.18) |

are constants for similarity solutions, we have

are constants for similarity solutions, we have | (3.19) |

In this case, we have

In this case, we have | (3.20) |

= constant,

= constant, | (3.21) |

| (3.22) |

In this case, the constant in the right hand side of (2.20) must be zero, and the shock velocity is variable and so

In this case, the constant in the right hand side of (2.20) must be zero, and the shock velocity is variable and so | (3.23) |

| (3.24) |

| (3.25) |

| (3.26) |

| (3.27) |

| (3.28) |

| (3.29) |

| (3.30) |

| (3.31) |

| (3.32) |

| (3.33) |

| (3.34) |

| (3.35) |

| (3.36) |

| (3.37) |

| (3.38) |

| (3.39) |

| (3.40) |

| (3.41) |

| (3.42) |

, similarity solution exists only when

, similarity solution exists only when  is constant, i.e. only when the initial density

is constant, i.e. only when the initial density  is constant. The problem with the flow of a non-ideal gas is different from that of the perfect gas problem. In the latter case, similarity solution exists for initial density varying as some power of distance (Rogers[20], Rosenau[24]), but it is not true for the problem with the flow of a non-ideal gas.In addition to the shock conditions(3.37) to (3.42), the condition to be satisfied at the inner boundary surface is that the velocity of the fluid is equal to the velocity of inner boundary itself. This kinematic condition, from equations (3.2) and (3.28), can be written as

is constant. The problem with the flow of a non-ideal gas is different from that of the perfect gas problem. In the latter case, similarity solution exists for initial density varying as some power of distance (Rogers[20], Rosenau[24]), but it is not true for the problem with the flow of a non-ideal gas.In addition to the shock conditions(3.37) to (3.42), the condition to be satisfied at the inner boundary surface is that the velocity of the fluid is equal to the velocity of inner boundary itself. This kinematic condition, from equations (3.2) and (3.28), can be written as | (3.43) |

| (3.44) |

| (3.45) |

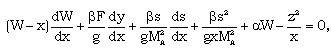

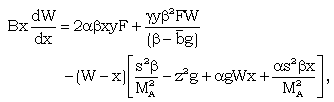

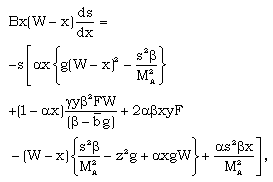

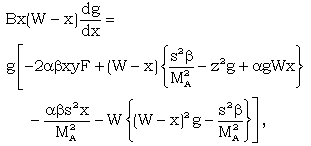

| (3.46) |

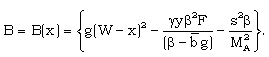

| (3.47) |

| (3.48) |

| (3.49) |

,

, ,

,  , M and

, M and  , to obtain W, g, s, y and z.

, to obtain W, g, s, y and z.4. Results and Discussion

- Similarity considerations led to the following relations among the constants

, d and

, d and  :

: | (4.1) |

| (4.2) |

;(ii) The decreasing velocity shock

;(ii) The decreasing velocity shock  Therefore, for the purpose of numerical calculations, we choose

Therefore, for the purpose of numerical calculations, we choose  , -0.5 which correspond, respectively, to the following two sets of values of the constants:(i)

, -0.5 which correspond, respectively, to the following two sets of values of the constants:(i)  ,

,  ,

,  , and (ii)

, and (ii)  ,

,  ,

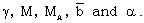

,  .The solution of the differential equations (3.44) to (3.48) with boundary conditions (3.37) to (3.42) depends on five constant parameters

.The solution of the differential equations (3.44) to (3.48) with boundary conditions (3.37) to (3.42) depends on five constant parameters  Numerical integration of these differential equations is performed to obtain the reduced variables W, z, g, y, s, starting from the shock surface to the inner expanding surface for

Numerical integration of these differential equations is performed to obtain the reduced variables W, z, g, y, s, starting from the shock surface to the inner expanding surface for

-0.5 (Rosenau and Frankenthal[25], Rosenau[24], Vishwakarma and Yadav[26], Vishwakarma and Singh[27]). For a fully ionized gas

-0.5 (Rosenau and Frankenthal[25], Rosenau[24], Vishwakarma and Yadav[26], Vishwakarma and Singh[27]). For a fully ionized gas  , and therefore it is applicable to stellar medium. Rosenau and Frankenthal[25] have shown that the effects of magnetic field on the flow-field behind the shock are significant when

, and therefore it is applicable to stellar medium. Rosenau and Frankenthal[25] have shown that the effects of magnetic field on the flow-field behind the shock are significant when  . Therefore the above values of

. Therefore the above values of  are taken for calculations in the present problem. The value

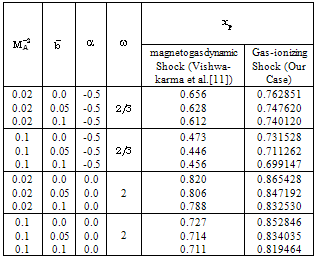

are taken for calculations in the present problem. The value  corresponds to the perfect gas case. The results are shown in figures 1-5. Values of

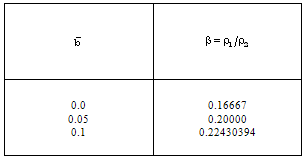

corresponds to the perfect gas case. The results are shown in figures 1-5. Values of  (the reduced position of the inner expanding surface) and the density ratio across the shock front

(the reduced position of the inner expanding surface) and the density ratio across the shock front  are shown in tables 1 and 2 for different cases.

are shown in tables 1 and 2 for different cases.

|

|

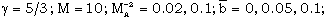

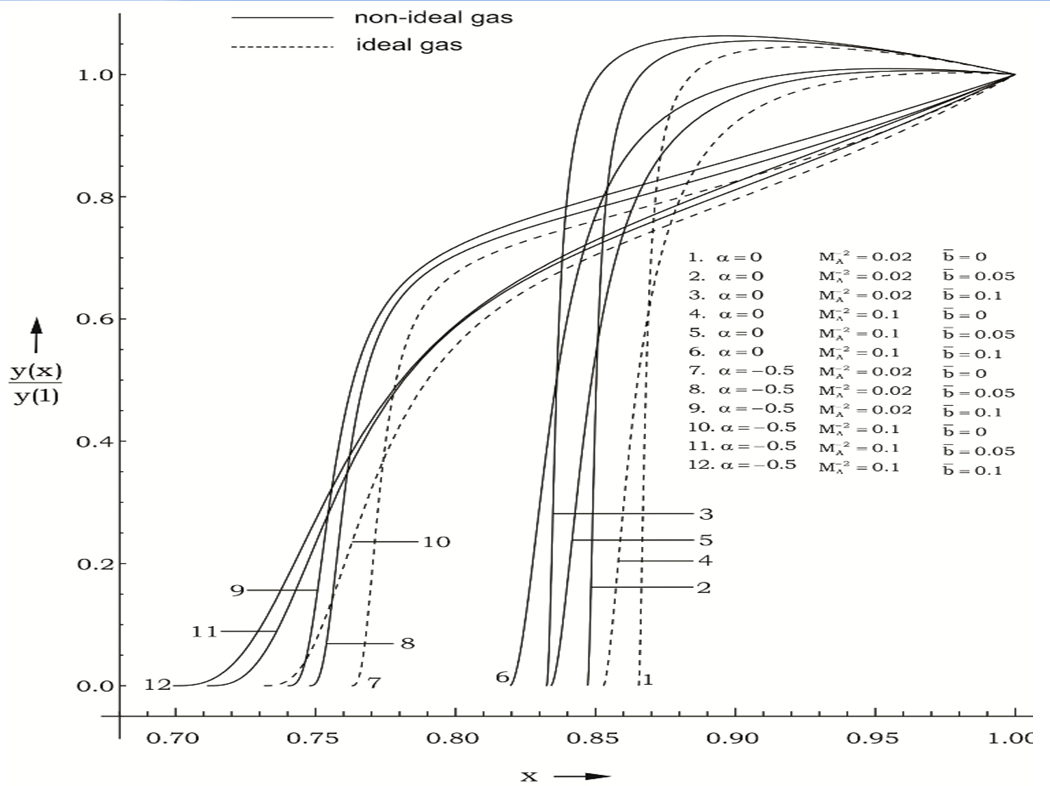

| Figure 1. Variation of the reduced radial velocity in the flow-field behind the shock front |

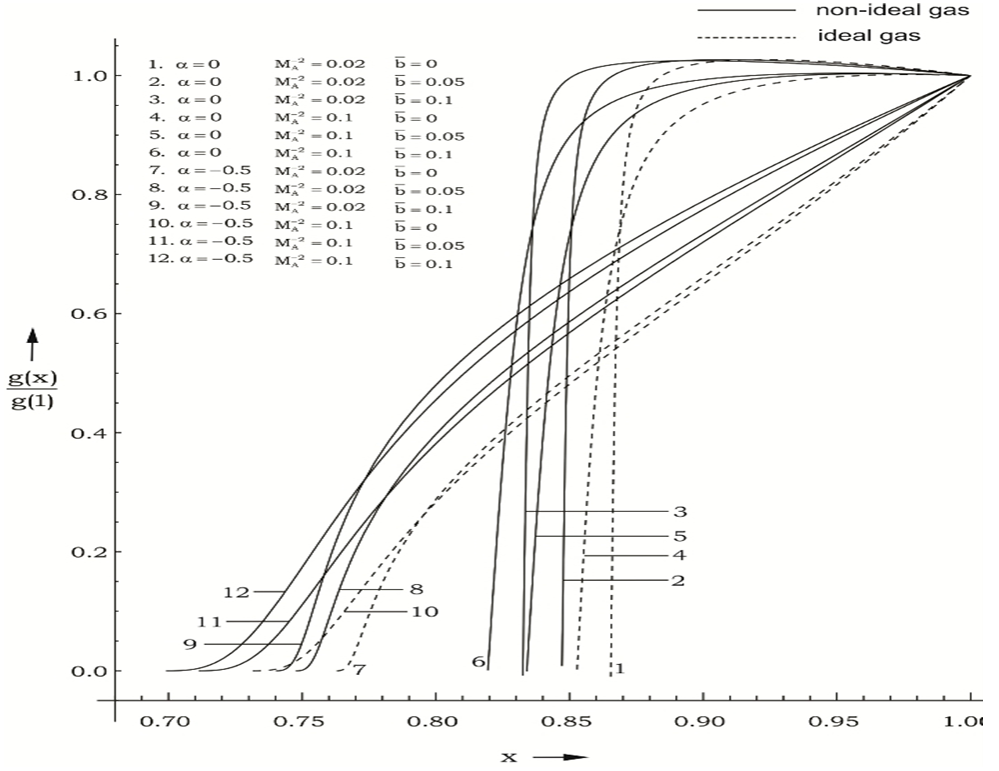

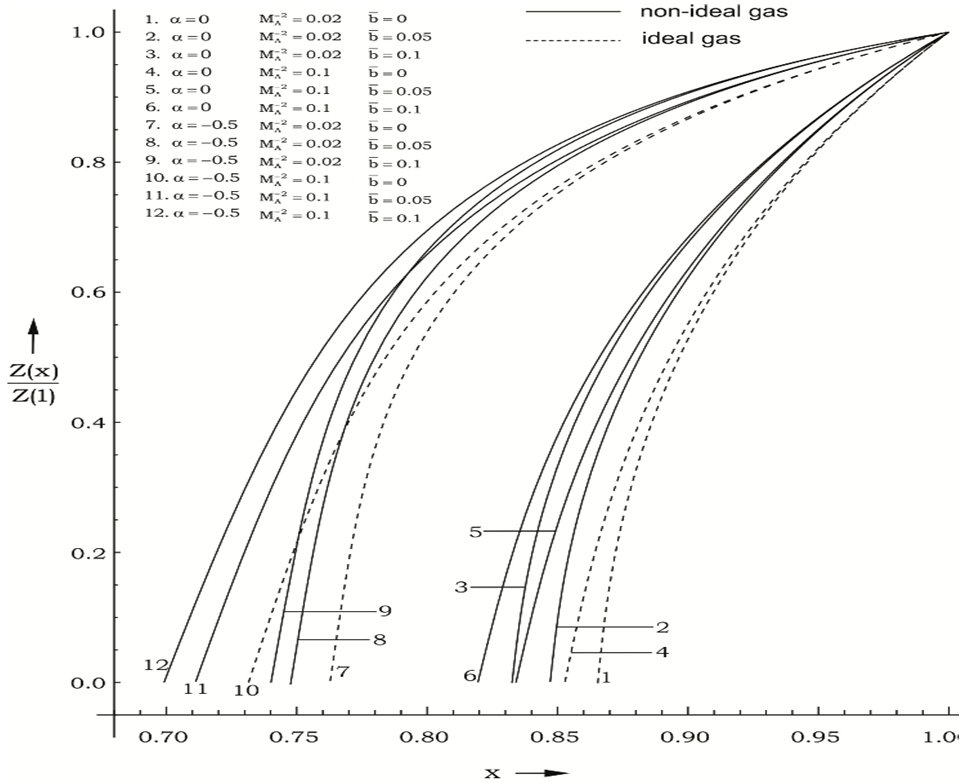

| Figure 2. Variation of the reduced azimuthal magnetic field in the flow-field behind the shock front |

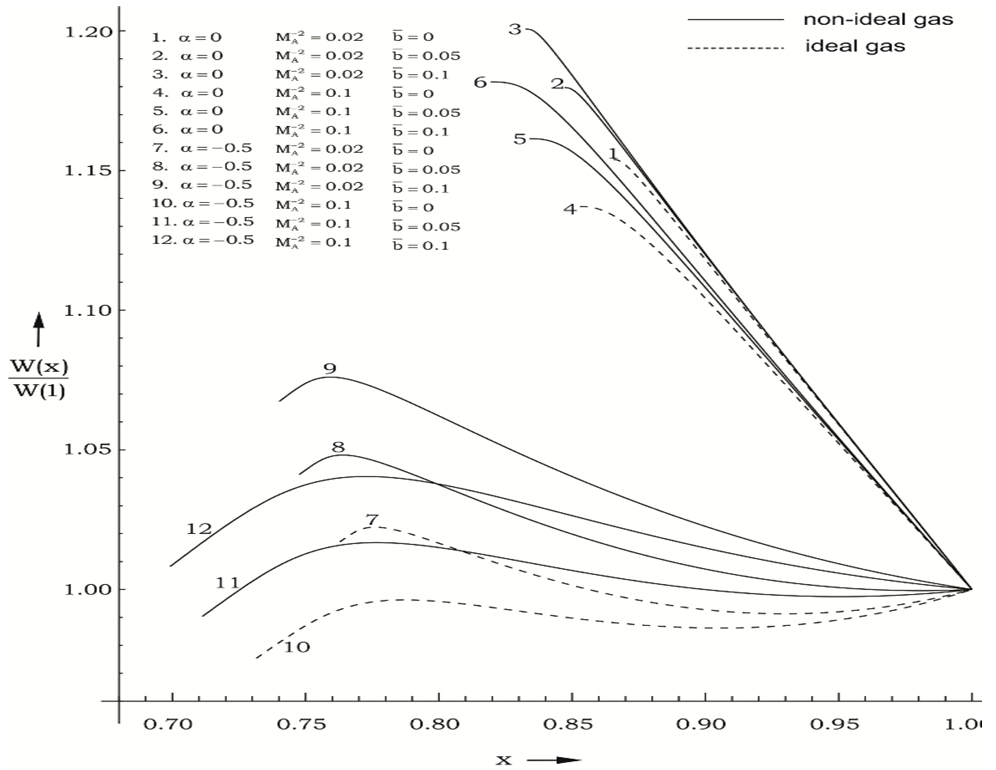

| Figure 3. Variation of the reduced density in the flow-field behind the shock front |

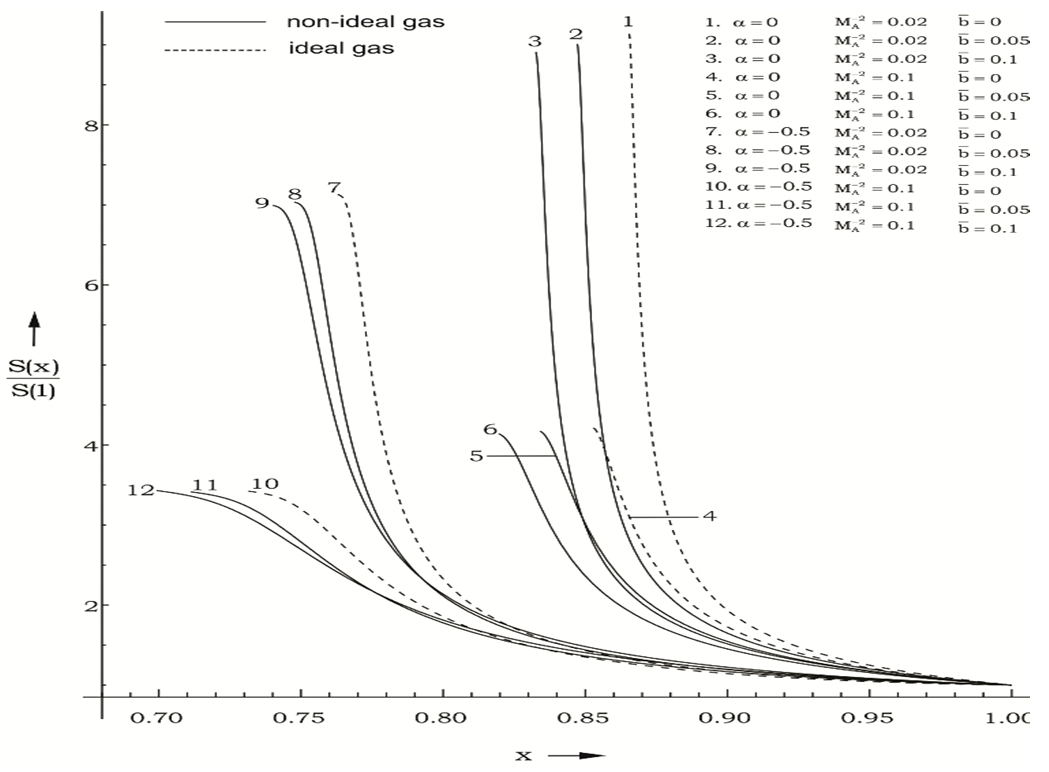

| Figure 4. Variation of the reduced pressure in the flow-field behind the shock front |

| Figure 5. Variation of the reduced azimuthal velocity in the flow-field behind the shock front |

whereas its increase is very slow in almost all the cases of

whereas its increase is very slow in almost all the cases of  . In these cases (

. In these cases ( ), it starts to decrease after attaining a maximum near the inner surface. The nature of the radial velocity profile in the flow-field behind a gas-ionizing shock is different from that behind a magnetogasdynamic shock, where it decreases from shock front to inner surface in the cases of

), it starts to decrease after attaining a maximum near the inner surface. The nature of the radial velocity profile in the flow-field behind a gas-ionizing shock is different from that behind a magnetogasdynamic shock, where it decreases from shock front to inner surface in the cases of  (Vishwakarma et al.[11]).Figure 2 shows that the magnetic field s increases abruptly near the inner contact surface when the initial magnetic field is weak (

(Vishwakarma et al.[11]).Figure 2 shows that the magnetic field s increases abruptly near the inner contact surface when the initial magnetic field is weak ( ). This behaviour of the magnetic field is removed in the cases of strong initial magnetic field (

). This behaviour of the magnetic field is removed in the cases of strong initial magnetic field ( ). The magnetic field does not exhibit the behaviour of abrupt increase near the inner surface in the case of magnetogasdynamic shock (see figure 3 of Vishwakarma et al.[11]). Figures 3, 4 and 5 show that the density g, pressure y and azimuthal velocity z decrease from shock front to the inner contact surface. The density and pressure fall abruptly near the inner surface when

). The magnetic field does not exhibit the behaviour of abrupt increase near the inner surface in the case of magnetogasdynamic shock (see figure 3 of Vishwakarma et al.[11]). Figures 3, 4 and 5 show that the density g, pressure y and azimuthal velocity z decrease from shock front to the inner contact surface. The density and pressure fall abruptly near the inner surface when  and

and  . This tendency of density and pressure is reduced if

. This tendency of density and pressure is reduced if  is decreased (

is decreased ( ) or if

) or if  is increased (

is increased ( ).From tables 1 and 2 and figures 1 to 5, it is found that the effects of an increase in the value of

).From tables 1 and 2 and figures 1 to 5, it is found that the effects of an increase in the value of  (i.e. the effects of an increase in the strength of ambient magnetic field) are (i) to decrease the radial velocity and azimuthal magnetic field at a point in the flow-field behind the shock front, but to increase the azimuthal velocity (see figures 1, 2 and 5);(ii) to decrease the density and pressure, except in a region near the inner contact surface. The decrease in density is small for

(i.e. the effects of an increase in the strength of ambient magnetic field) are (i) to decrease the radial velocity and azimuthal magnetic field at a point in the flow-field behind the shock front, but to increase the azimuthal velocity (see figures 1, 2 and 5);(ii) to decrease the density and pressure, except in a region near the inner contact surface. The decrease in density is small for  in comparison to that for

in comparison to that for  (see figures 3 and 4);(iii) to decrease the slopes of the profiles of the density, pressure and azimuthal magnetic field, i.e. to reduce the tendency of abrupt fall of the density and pressure and abrupt increase of the azimuthal magnetic field as we move inwords from the shock front (see figures 2, 3 and 4); and(iv) to increase the distance of the inner contact surface from the shock front (see table 1), but this increase is small in comparison with that in the case of magnetogasdynamic shock studied by Vishwakarma et al.[11].Thus the increase in the strength of the magnetic field has decaying effect on the ionizing shock wave, but it is less in comparison with that in the case of magnetogasdynamic shock.The effects of an increase in the value of the parameter of the non-idealness of the gas

(see figures 3 and 4);(iii) to decrease the slopes of the profiles of the density, pressure and azimuthal magnetic field, i.e. to reduce the tendency of abrupt fall of the density and pressure and abrupt increase of the azimuthal magnetic field as we move inwords from the shock front (see figures 2, 3 and 4); and(iv) to increase the distance of the inner contact surface from the shock front (see table 1), but this increase is small in comparison with that in the case of magnetogasdynamic shock studied by Vishwakarma et al.[11].Thus the increase in the strength of the magnetic field has decaying effect on the ionizing shock wave, but it is less in comparison with that in the case of magnetogasdynamic shock.The effects of an increase in the value of the parameter of the non-idealness of the gas  are (i) to increase the radial and azimuthal velocities at a point in the flow-field behind the shock but to decrease the azimuthal magnetic field, in general. The increase in the radial velocity is significant in the cases when

are (i) to increase the radial and azimuthal velocities at a point in the flow-field behind the shock but to decrease the azimuthal magnetic field, in general. The increase in the radial velocity is significant in the cases when  (see figures 1, 2 and 5);(ii) to increase the density and pressure, in general (see figures 3 and 4); and(iii) to increase the distance between inner contact surface and the shock front, and

(see figures 1, 2 and 5);(ii) to increase the density and pressure, in general (see figures 3 and 4); and(iii) to increase the distance between inner contact surface and the shock front, and  (see tables 1 and 2).Therefore the non-idealness of the gas has decaying effect on the ionizing shock wave as in the case of magnetogasdynamic shock. The effect of an increase in the value of the index for variation of azimuthal magnetic field

(see tables 1 and 2).Therefore the non-idealness of the gas has decaying effect on the ionizing shock wave as in the case of magnetogasdynamic shock. The effect of an increase in the value of the index for variation of azimuthal magnetic field , i.e. the effects of an increase in the value of the index for variation of the angular velocity of the ambient medium d are(i) to increase the shock velocity (see equation (3.18));(ii) to decrease the distance of inner expanding surface from the shock front. It means that the shock is stronger when the ambient magnetic field is uniform (

, i.e. the effects of an increase in the value of the index for variation of the angular velocity of the ambient medium d are(i) to increase the shock velocity (see equation (3.18));(ii) to decrease the distance of inner expanding surface from the shock front. It means that the shock is stronger when the ambient magnetic field is uniform ( ) in comparison with that when it is decreasing (

) in comparison with that when it is decreasing ( ). It also means that the shock is stronger when the angular velocity of the ambient medium is slowly decreasing (see the relations (2.19) and (3.20)); and(iii) to increase the slopes of profiles of all the flow variables in the flow-field behind the shock. (see figures 1-5).

). It also means that the shock is stronger when the angular velocity of the ambient medium is slowly decreasing (see the relations (2.19) and (3.20)); and(iii) to increase the slopes of profiles of all the flow variables in the flow-field behind the shock. (see figures 1-5).5. Conclusions

- In the present paper, similarity solutions are obtained for the flow-field behind a gas-ionizing cylindrical shock wave propagating in a rotating non-ideal gas in presence of an azimuthal magnetic field. On the basis of this study one may draw the following conclusions. (i) the shock velocity varies as the ambient azimuthal velocity (i.e. as the ambient magnetic field).(ii) the presence of magnetic field has decaying effect on the ionizing shock wave but it is less in comparison with that on the magnetogasdynamic shock; (iii) the non-idealness of the gas also has decaying effect on the ionizing shock wave, and it is almost of the same intensity as that on the magnetogasdynamic shock; (iv) in the case when the initial magnetic field or the initial angular velocity of the medium is decreasing with distance (i.e. when

), the nature of the radial velocity profiles in the flow-field behind the ionizing shock is significantly different from that behind the magnetogasdynamic shock; and(v) when the initial magnetic field is weak (

), the nature of the radial velocity profiles in the flow-field behind the ionizing shock is significantly different from that behind the magnetogasdynamic shock; and(v) when the initial magnetic field is weak ( ) the magnetic field increases abruptly near the inner contact surface. The magnetic field does not exhibit this behavior in the case of the magnetogasdynamic shock.

) the magnetic field increases abruptly near the inner contact surface. The magnetic field does not exhibit this behavior in the case of the magnetogasdynamic shock. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML for

for  ,

,  and various values of

and various values of  , and

, and

across the shock front for

across the shock front for  0.05, 0.1,

0.05, 0.1,  and

and