S. I. Durowaye1, A. G. F Alabi2, O. I. Sekunowo1, B. Bolasodun1, I. O. Rufai1

1Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos, Nigeria

2Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

Correspondence to: S. I. Durowaye, Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The importance of mild steel to various industries due to the industrial revolution is very enormous. Hence, various methods of corrosion control are in use. These methods and processes depend on the nature and type of environment in which the material will be used. The inhibitive effect of sodium sulphite (Na2SO3) on the corrosion of mild steel in bore-hole water of different pH values of 7.20, 8.10, 9.10, 10.10, 11.0 and 11.10 using 1M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution at room temperature was investigated by chemical technique. It is shown that the application of Na2SO3 in desirable limited amount (2ml) in bore-hole water of pH value 11.10 has the least corrosion rate of 5.504 mpy whereas its application in excess amount (4ml) has a higher corrosion rate of value of 13.368 mpy. Hence, sodium sulphite in limited amount inhibited the corrosion of mild steel while excess amount of it increased the rate of corrosion.

Keywords:

Mild Steel, Na2SO3, NaOH, Inhibitive Effect, Bore-hole Water, Corrosion, pH, Conductivity, Optical Emission Spectrometer

Cite this paper: S. I. Durowaye, A. G. F Alabi, O. I. Sekunowo, B. Bolasodun, I. O. Rufai, Inhibitive Effect of Sodium Sulphite on Corrosion of Mild Steel in Bore-hole Water Containing 1M Sodium Hydroxide Solution, American Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 11-17. doi: 10.5923/j.materials.20140401.03.

1. Introduction

Corrosion of industrial metals is one of the oldest problems that have ever challenged the industrial world and is defined variously[1, 2, 3]. Corrosion is the gradual physiochemical destruction of materials by the action of environment. It is also known as the deterioration of materials or its properties because of reaction with its environment. Most metals exist in nature in combined forms such as oxides, hydroxides, carbonates, sulphides, sulphates and silicates. The extraction of metals from their ores requires a considerable amount of energy. The isolated metals therefore can be regarded as being in a much higher energy state than in their corresponding ores, and they will show a natural tendency to return to their lower energy or combined state. Thus corrosion of metals can be regarded as the reverse process of that of reducing from their ores[4].Metallic material constitutes a great part of construction material elements in industries, agricultural equipment, oil and gas and petrochemical, medical services, process and allied industries. In these industries, the metallic material as a result of interaction with its environment loses its integrity over a period of time[5]. As such, the material cannot perform the intended function effectively and reliably. Some of these environments are atmosphere, aqueous solution, solids, acids and bases, inorganic solvents, molten salts, liquid metals, human body etcetera. At times, the effect of the loss in integrity may be very severe as to result in loss of valuable production time, accident and in the extreme death. The cost associated with the problem is enormous and its influence in the economy of a nation is significant. It has been estimated that approximately 5% of industrialised nations’ income is spent on corrosion incidental problems. For instance, the cost of the problem to the U.S. economy is put at $297 billion annually[6]. The cost to the Nigerian economy is not available. However, a guess could be haphazard; and this is in the corridor of $3.2 billion annually[7]. Thus, a great effort is devoted to combating corrosion and its associated problems. Problems of corrosion are more pronounced in processing industry. A typical reference is agro-processing industries. The production of bio-compatible and bio-degradable industrial raw-material from purely agricultural sources has increased in recent years. For instance, ethanol is being produced from cassava tubers through multi processing stages. The factory processing of cassava produces the toxic compound hydrogen cyanide. The cyanide is very corrosive and is responsible for the corrosion of agro-processing equipment which is usually made of plain carbon steel. The corrosiveness of the cassava fluid is due to the cyanide ion in the cyanogenic glycosides whose concentrations vary widely as a result of genetic and environmental factors, location, seasons and soil types[8] and[9]. Beside the loss in functionality of the agro-processing equipment, the corrosion product may get into the final product. The quality of the end-product is thus affected. In food and agricultural industries, product quality, health and sanitation issues are major concerns. This is particularly true in the processing of cassava tuber which releases hydrogen cyanide to the environment. Hydrogen cyanide is a volatile liquid that is lethal. Its disposal is strictly based on health and safety regulations. Corrosion prevention options are many and have varied applications. Some of these methods include material selection, environmental alterations, design, coatings and cathodic protection. Perhaps, the most common and easiest way of preventing corrosion is through the judicious selection of material once the corrosion environment has been characterised. In real situations, however, it is not always sensible to employ the material that renders the optimum resistance, apparently because of the cost involved. Equally, changing the character of the environment hardly offers tremendous potential without affecting the optimal productivity of the process. Corrosion reduction in metallic materials has been effected greatly with the use of inhibitors[10]. These are substances, that when added in relatively low concentrations to the environment decreases its corrosiveness. The inhibitors are either organic or inorganic in nature and may be applied singly or in combinations[11]. Corrosion control is an important activity of technical, economical, environmental and aesthetical importance. Thus, the search for efficient corrosion inhibitors has become a necessity to secure metallic materials against unmitigated degradation. Corrosion of mild steel is of great practical interest because mild steel is widely used in the oil, gas and offshore environments for pipelines, flow-lines, platforms, down-hole tubular equipments, well heads, industrial vessels etc. Corrosion inhibition is being extensively employed in minimising metallic wastage of engineering materials in service[12]. In this research, the effect of the inhibition efficiency of Sodium Sulphite (Na2SO3) on the corrosion rate of mild steel in borehole water using 1M Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) is experimentally investigated and presented.

2. Experimental Details

The mild steel used in this study has a carbon content of approximately 0.2%. Nine mild steel test specimens (coupons) of dimensions 3 x 1 x 0.15cm were cut from mild steel sheet of 0.15cm in thickness. They were labelled A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H and I. The composition analysis of the specimens was determined using an optical emission spectrometer (OES) ARL 3460B model. On each specimen, a hole of 1mm diameter was drilled near one of the ends to allow for easy hanging of the specimen into the solution using a thread. The specimens’ surfaces were prepared with 220 grit paper which gave good reactive surfaces. The specimens were degreased in ethanol, air dried and etched in 5% concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) for 30 seconds and weighed before immersion in the test environment. Specimen A was suspended in room air environment while each of B, C, D, E, F, G, H and I, were immersed in eight separate 250 ml open beakers containing 200 ml of bore-hole water of different pH values. Different volumes of 1M NaOH solution were added to the water in the eight beakers in order to vary their pH values after which 2 ml of Na2SO3 solution was added to the solutions containing specimens B, C, D, E and F. Double amount (4 ml) of Na2SO3 solution was added to the solutions containing specimens G, H and I. The pH and conductivity of all the solutions before and after the experiment were measured and recorded. Initial pH values of 7.20, 8.10, 9.10, 10.10, 11.0 and 11.10 were used. The variation of weight loss was monitored after 240 hours immersion per specimen/coupon at room temperature. After 240 hours, the specimens were taken out, immersed in dilute H2S04 (Sulphuric acid of specific gravity 1.84) at room temperature, scrubbed with a bristle brush, rinsed in distilled water, rinsed in ethanol, air-dried and re-weighed. The weight loss was calculated in gramme (g) as the difference between the initial weight and the final weight after removal of the corrosion products. The reduction of the thickness as a function of time was calculated. The experimental readings were recorded to the nearest 0.0001g on a Mettler digital analytical balance (digital analytical balance with sensitivity of ± 1mg). Corrosion rate in mil/yr was determined using the equation[13]:  | (1) |

Where: R = corrosion rate (mil/yr) K = constant and its value is 534 for (mil/yr)W1 = initial weight of specimen before corrosion in milligrams (mg)W2 = final weight of specimen after corrosion in milligrams (mg)δ = density of specimen in g/mm3 = 7.86 x 10-3 g/mm3A = total surface area of specimen exposed (mm2)t = time of exposure (hr)

3. Results and Discussion

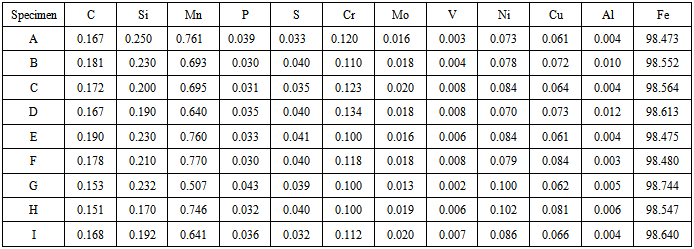

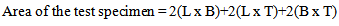

The spectrochemical analysis shown in table 1 reveals that the mild steel specimens used in this study have an iron content of approximately 99% with other trace elements residued from metal extraction process. The levels of these trace elements are insignificant to influence the chemistry of the behaviour of the steel samples in the corrodant and inhibitor media. | (2) |

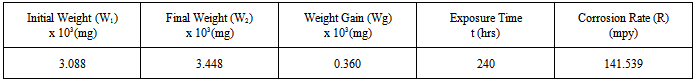

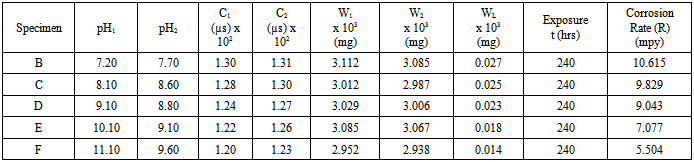

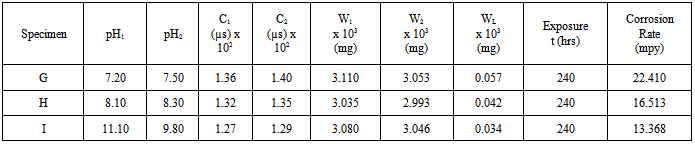

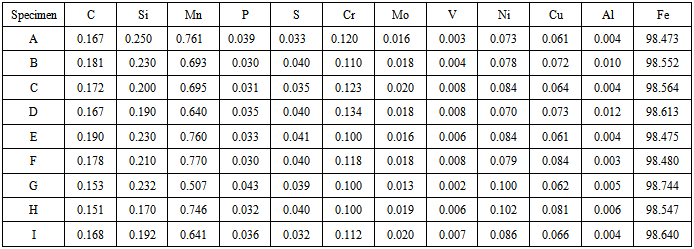

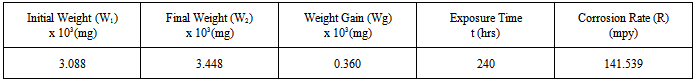

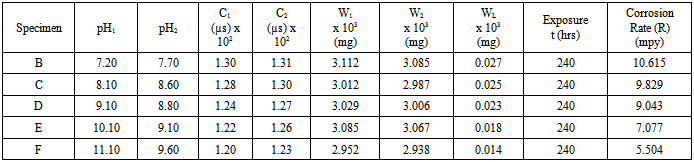

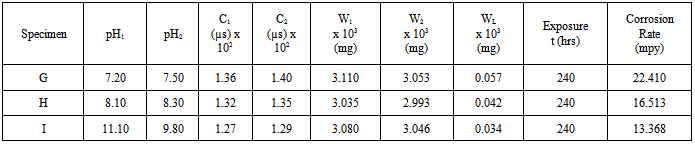

Where:L = length of test specimen = 3cmB = breadth of test specimen = 1cmT = thickness of test specimen = 0.15cmUsing equation (2), Area of the specimen = 7.20cm2 = 7.20 x 102mm2. The mild steel used in this study has a carbon content of approximately 0.2% and the density (δ) is 7.86 x 10-3g/mm3.Using equation (1), the corrosion rate (R) of the specimen suspended in air at room temperature in the laboratory is 141.539mpy.pH1 and pH2 represent the pH of the various solutions before and after the experiment.C1 and C2 represent the conductivity of the various solutions before and after the experiment.W1 and W2 represent the weight of the various specimens before and after the experiment.WL represents the weight loss of the various specimens after the experiment.Table 1 shows the composition analysis of the specimens. Table 2 shows the corrosion rate of specimen suspended in air at room temperature for 240 hrs. Table 3 shows the weight loss and corrosion rate of the specimens in bore-hole water of different pH with addition of 2ml Na2SO3 at room temperature for 240 hrs. Table 4 shows the weight loss and corrosion rate in bore-hole water of different pH with addition of excess (4ml) Na2SO3 at room temperature for 240 hrs.

Table 1. Chemical composition of mild steel specimens (%)

|

| |

|

Table 2. Corrosion of specimen suspended in air at room temperature for 240 hrs

|

| |

|

Table 3. Corrosion in bore-hole water of different pH with addition of 2ml Na2SO3 at room temperature

|

| |

|

Table 4. Corrosion in bore-hole water of different pH with addition of excess (4ml) Na2SO3 at room temperature for 240 hrs

|

| |

|

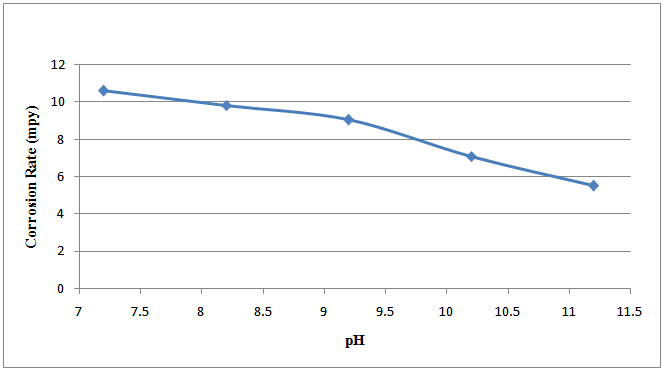

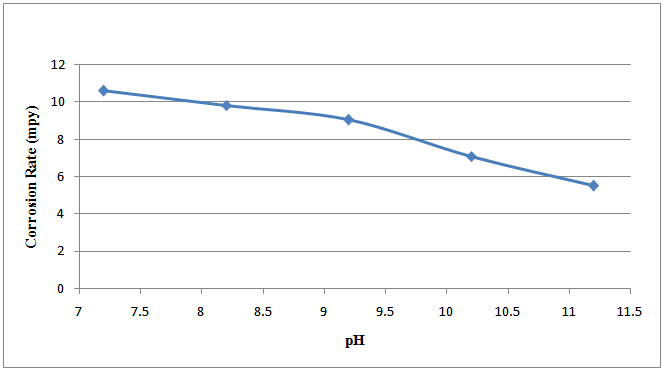

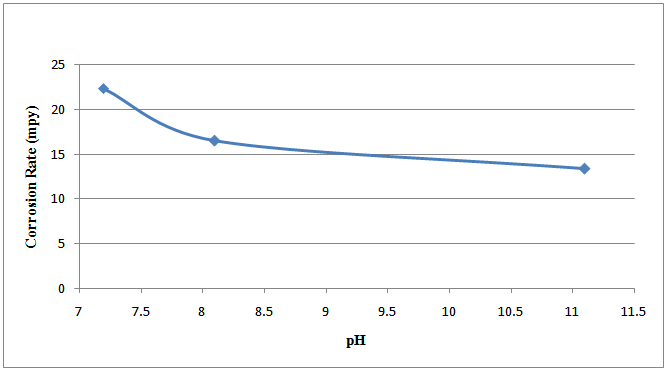

Figure 1 shows the plot of the corrosion rate against the pH of the specimens in bore-hole water with addition of 2ml Na2SO3 at room temperature.Figure 2 shows the plot of the corrosion rate against the pH of the specimens in bore-hole water with addition of excess (4ml) Na2SO3 at room temperature. | Figure 1. Corrosion rate against pH of specimens in bore-hole water with addition of 2ml Na2SO3 at room temperature |

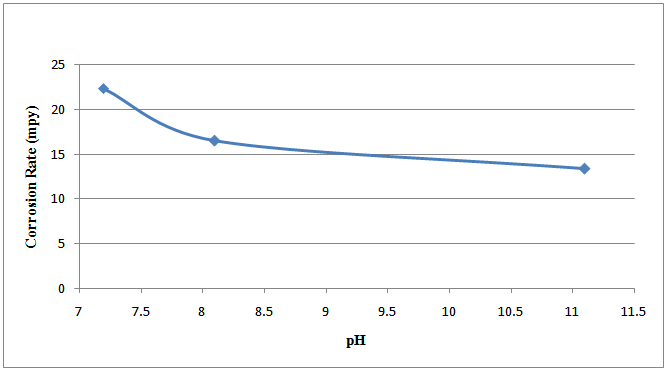

| Figure 2. Corrosion rate against pH of specimens in bore-hole water with addition of excess (4ml) Na2SO3 at room temperature |

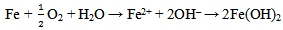

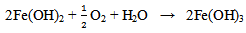

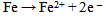

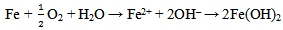

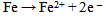

As indicated in table 2, the specimen that was exposed to the room air in the laboratory had an initial weight of 3.088(g) and a final weight of 3.448(g). An increase in weight of 0.360(g) in the test specimen was observed with a corrosion rate value of 141.539 mpy after 240 hrs of exposure. This is due to the corrosion product that adhered to the surface possibly due to the acidic environment in the laboratory. After about an hour of exposure to the room atmospheric air, the metallic bright gray colour had changed to yellowish- brown. Changes of the specimen surface seemed to have reached its climax by the 10th day (240 hrs) with a light-brown deposit (rust) which must have been due to its reaction with air and moisture. The mild steel specimen was exposed to moist air and reacted with oxygen in the air to form Fe(OH)3. This is due to the fact that the electrons produced as a result of oxidation of iron (Fe) is conducted through the metal and the iron ions diffused through the moist layer to another point on the specimen’s surface where oxygen is available. This process results into an electrochemical cell in which iron serves as the anode, oxygen as the cathode and the aqueous solution of ions as a salt bridge. The specimen corroded in the solution by an electrochemical mechanism involving its oxidation as ions according to:  | (3) |

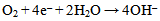

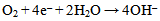

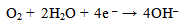

The excess electrons generated in the aqueous solution created hydroxyl ions[OH–] by the reduction of dissolved oxygen according to: | (4) |

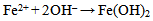

| (5) |

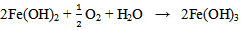

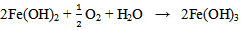

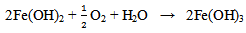

The reaction continues as the Fe(OH)2 reacts with more oxygen and moisture leading to:Fe3+ as Fe(OH)3 according to: | (6) |

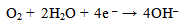

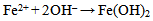

The compound Fe(OH)3 is a light-brown deposit, an insoluble compound known as rust which is formed as a consequence of oxidation[13, 14]. This shows that even in the laboratory, corrosion of mild steel specimen is possible. As indicated in table 3, the weight loss of the specimen in bore-hole water at pH value of 7.20 using 1M of sodium hydroxide solution (NaOH) with addition of 2ml Na2SO3 is 0.027(g). This decreased to 0.025(g) at pH value of 8.10 with the addition of the same amount of Na2SO3. The highest weight loss of 0.027(g) was recorded at pH value of 7.20 while the lowest weight loss of 0.014(g) was recorded at pH value of 11.10. The weight loss at pH value of 11.10 is almost half of the value at pH value of 7.20. It is obvious that the weight loss decreased with increase in the pH values from 7.20 to 11.10. As indicated in table 3, the highest corrosion rate of 10.615mpy was recorded in specimen B in solution with pH value of 7.20 while the lowest corrosion rate value of 5.504mpy was recorded in specimen F in solution with the highest pH value of 11.10. Corrosion rate of specimen B in solution with pH value of 7.20 is almost twice that of specimen F in solution with pH value of 11.10 with the addition of 2ml of sodium sulphite. These show that the specimens have reacted with their corrosive medium as: In the first stage, Fe in the specimens is oxidised to Fe2+ as Fe(OH)2 according to: | (7) |

The reaction continues in the second stage as the Fe(OH)2 reacts with more oxygen and water resulting into oxidation to Fe3+ as Fe(OH)3 according to:  | (8) |

The compound Fe(OH)3 is an insoluble compound known as rust which is formed as a consequence of oxidation[13, 14]. The specimens corroded in the solution by an electrochemical mechanism involving their dissolution as ions at the anodic site due to oxidation: | (9) |

The excess electrons generated in the solution created hydroxyl ions[OH–] by the reduction of dissolved oxygen which enhances uniform corrosion at the cathodic site according to: | (10) |

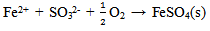

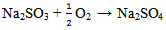

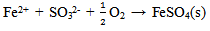

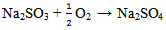

The corrosion rate of the specimens is associated with the flow of electrons with the two reactions involving oxidation (in which the specimens ionised) and reduction occurring at the anodic and cathodic sites respectively, on the surfaces of the specimens. Generally, the specimens’ surfaces consist of both anodic and cathodic sites, depending on segregation, microstructure, stress, etc[15].The graphical representations of the corrosion rate of the mild steel specimens with increase in the pH of the solutions are shown in figures 1 and 2. The graph lines decrease as the pH values increase. This is attributed to the fact that sodium sulphite formed a protective film on the mild steel specimens’ surfaces against the corrosive effect of the solutions thus, making a small part of the mild steel specimens to be exposed to the corrosive medium. This describes the effectiveness of the inhibitor (Na2SO3) in retarding corrosion process[16]. An insoluble layer of corrosion products was left behind in the process of corrosion and these corrosion products were very dense, adherent, had considerable strength, and formed a barrier against further corrosion[17]. Sodium sulphite (Na2SO3) acted as a cathodic inhibitor by mopping up aerated oxygen in the corrosive solution and in the process converted the iron ions to ferric sulphate as illustrated in the half cell reaction:  | (11) |

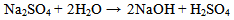

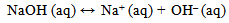

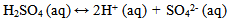

The thin film ferric sulphate formed on the specimens’ surfaces interfered with the cathodic reaction and retarded the progression of the corrosion process. The retardation of the corrosion process was effected by slowing down the reaction due to the resistance of the film present on the cathodic surface and slow diffusion of ions through the layer[16]. Comparing the corrosion rate of table 3 with 4, the rate of corrosion is higher in specimens G, H and I to which excess (4ml) of sodium sulphite was added. For example, the solution of specimen F which has a pH value of 11.10 before the experiment to which 2ml of Na2SO3 was added, has a corrosion rate of 5.504mpy whereas, the solution of specimen I of the same pH value of 11.10 before the experiment to which 4 ml of Na2SO3 was added, has a corrosion rate of 13.368mpy. This is twice the corrosion rate of specimen F. The same situation is observed in specimens B and G. This shows that excess sodium sulphite increased the rate of corrosion.  | (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

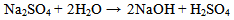

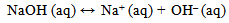

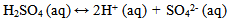

The excess sodium sulphite reacted with the dissolved oxygen in the solution to form sodium sulphate which reacted with water to form sodium hydroxide and sulphuric acid. This increased the electrochemical reaction by the introduction of more ions thereby increasing the corrosivity, conductivity and acidity of the solutions. This is responsible for the high corrosion rate in specimens G, H and I.

4. Conclusions

The pH value of 11.10 gave the lowest corrosion rate value of 5.504mpy when 2ml of sodium sulphite was used while the highest corrosion rate value of 22.410mpy was recorded at pH value of 7.20 when 4ml of sodium sulphite was used. The results showed that sodium sulphite of desirable specified quantity (2ml) can be used as an inhibitor because it scavenges oxygen in the solution. It has also been shown that excess of sodium sulphite increased the corrosion rate because more ions are introduced into the solutions thus, electrochemical reaction is increased. Since huge financial losses are always incurred by the replacement of corroded parts, industries are advised to strictly comply with instructions for the application of inhibitors to reduce corrosion rate. From the results of this study, it is recommended that industries should start their solutions at pH 11.10 to reduce corrosion rate in mild steel using Na2SO3 as an inhibitor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Professor G.I. Lawal, Head of Department, Metallurgical and Materials Engineering Dept, University of Lagos for his tremendous support and Dr. T.M. Fashina, Senior Lecturer, Department of Chemistry, University of Lagos, for her valuable suggestions.

Notations

P = corrosion rate (mil/yr)K = constant and its value is 534 for (mil/yr)W1 = initial weight of specimen before corrosion in milligrams (mg)W2 = final weight of specimen after corrosion in milligrams (mg)δ = density of mild steel (specimen) g/mm3 = 7.86 x 10-3 g/mm3A = Total surface area of specimen (mm2)t = time of exposure (hr)pH = – log[H+] C = Conductivity of solutions (µs) x 102

References

| [1] | Mailliard, O. (1985) "Polyurethane Resin Base External Coating for the Protection of Buried Ductile Iron Mains", Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on the Internal and External protection of Pipes, Nice, France, Paper F1. |

| [2] | Trethewey, K. R. and Chamberlain, J. (1995): ‘‘Corrosion for Science and Engineering’’. 2nd ed. Addison Wesley Longman Limited, England. |

| [3] | Callister, W. D.(1996): ‘‘Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction’’. 4th edition. John Wiley and Sons, Inc, New york. |

| [4] | Choudary, R.B. (2007): ‘‘Material Science and Metallurgy’’. First Reprint: 2007, pp 722. ISBN: 81-7409-176-6. |

| [5] | Callister, W.D. ‘‘Materials Science and Engineering’’. 4th ed. John – Wiley, New York, 1997. |

| [6] | www.nace.org retrieved Friday July 6, 2007. |

| [7] | CIA-TheWorldfactbook-Nigeria,www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/ni.html. July 2006. |

| [8] | Ermans, A. M., Mbulamoko, M. N., Delange, F and Ahluwalia, R. eds., ‘‘Role of Cassava in the etiology of endemic goiter and cretinism’’. International Development Research Centre, Ottawa-Ontario, 182 pp, 1980. |

| [9] | JECFA, ‘‘Cyanogenic glycosides in Toxicological Evaluation of Certain food Additives and Naturally Occurring Toxicants’’, 39th Meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Additives Geneva, Available at http://www.inchem.org/documents/jecfa/jecmono/v30je18.htm,1993. |

| [10] | www. Corrosion-doctors.org /inhibitors |

| [11] | Ashworth, V. Corrosion Protection Techniques: Industrial Problems, Treatments and Control Techniques, Proceedings of the First Arabian Conference on Corrosion held in Kuwait between 4-8th February, 1984, Pergamon Press, Vol. 2, pp. 492, 1987. |

| [12] | Aver, S.H. (1974): ‘‘The Introduction to Physical Metallurgy’’. 2nd Edition McGraw-Hill Inc., New York, pp. 86-92. |

| [13] | Choudary, R.B. (2007): ‘‘Material Science and Metallurgy’’. First Reprint: 2007. ISBN: 81-7409-176-6. |

| [14] | Donald, R. A (1994): ‘‘The Science and Engineering of Materials’’. 3rd ed. pp 721. ISBN: 0-534-93423-4. |

| [15] | Smallman, R.E; Bishop, R.J. ‘‘Modern Physical Metallurgy and Materials Engineering’’. Sixth edition, 1999. ISBN 0 7506 4564 4. |

| [16] | Amuda, M. O. H., Lawal, G. I and Soremekun, O. O (2008): ‘‘Improving the Corrosion Inhibitive Strength of Sodium Sulphite in Hydrogen Cyanide Solution Using Sodium Benzoate’’. Leonardo Electronic Journal of Practices and Technologies ISSN 1583-1078. p. 63-75. |

| [17] | CISPI (Assessed July 2008), ‘‘Corrosion Resistance’’. http://www.cispi.org/cgi-bin/fmsearch/fmsearch.cgi. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML