-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

p-ISSN: 2168-457X e-ISSN: 2168-4588

2020; 8(1): 11-22

doi:10.5923/j.m2economics.20200801.03

Received: Sep. 27, 2020; Accepted: Oct. 24, 2020; Published: Nov. 15, 2020

Factors Affecting Private Investment in Ethiopian Industry Sector: The Case of Sugar Factories

Abraham Demissie Chare

Ethiopian Sugar Corporation, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Abraham Demissie Chare, Ethiopian Sugar Corporation, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This article aims to examine the factors affecting the private sector involvement in Ethiopia’s sugar sector privatization process. The study is analytical and employs a mixed method. 78 participants filled out a questionnaire that comprises 30 items in 5 points scale, and 13 individuals took part in two rounds of Focus Group Discussions. The study reveals fifteen major issues relating to the legal and policy arrangement, political, socio-economic, and market that have been determining the success privatization initiative. While launching the initiative to privatize the enterprise government has solely owned for decades is taken as a strength, lack of commitment to create an enabling legal and institutional environment are identified as major pitfalls of the sugar sector privatization initiative in Ethiopia. Thus, it would be soon to confidently conclude the initiative would succeed in the absence of the pre-requisites for any successful privatization initiative.

Keywords: Privatization, Sugar-sector, Market, Legal, Political, Economic, Social

Cite this paper: Abraham Demissie Chare, Factors Affecting Private Investment in Ethiopian Industry Sector: The Case of Sugar Factories, Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2020, pp. 11-22. doi: 10.5923/j.m2economics.20200801.03.

Article Outline

1. Study Background

- The Ethiopian sugar sector is one of the state-owned industries. The industry has been playing crucial roles in the Ethiopian economy through import substitution, sugar supply for the local market, and job creation. The eight operational sugar factories and five development projects have so far employed more than 62,000 people directly on a permanent and temporary basis. In the country in which unemployment is high, 1.79% in 2018 for instance, this number cannot be undermined, and, perhaps, significantly high when compared to other sectors [1]. Sugar sector development is the most capital intensive. Yet the Ethiopian government has been the sole owner of the sector from since 1950s in which the first sugar factory established in the country through 2010s when ambitious plan of filling the growing sugar demand and then earning foreign currency through export was implemented for 10 consecutive years. Starting from 2010, the 10 years Growth and Transformation plan (GTP), which was divided to five years, particularly, the Ethiopian government has been financing the renovation as well as new development sugar projects. With fierce finance short come due to high deficit (about 2.5% of GDP in 2018/19) [2,3], the government learned transferring ownership of the sugar sector is the first choice to get rid of the financial burden. Although privatization is a post-colonization economic reform movement globally, Ethiopia is a late starter even in Africa [4]. Privatization of the State-owned enterprises was embarked in Ethiopia in mid-1990s, after the downfall of the socialist Dergue regime. Urged by external pressure from the international financial institutions [5], the large debt leading to a high budget deficit, and poor growth prospects of the State-owned Enterprises [6], the current government which came into power in 1991 introduced the privatization initiative as part of the economic reform plan [6,7]. Changing the role and participation of the government in the economy to enable it to exert more effort on activities requiring its attention is one of the triplet objectives of sugar factories privatization.Even though available literatures vary in presenting the number of State-owned Enterprises privatized since 1994, a study estimated 360 to 400 [8]. Moreover, the program focused on limited industries such as textiles and apparel, food, beverages and tobacco, tanning, leather, and footwear and chemical products [9].On the contrary to this, the Ethiopian government has sustained and set up its own companies as a means to provide dynamism to the national economy. As a result, several enterprises are created in sectors such as transpiration, communication, banking and insurance, manufacturing, etc. The 13 sugar manufacturing mills along with the sugarcane estates across the country are among such properties that remained under state ownership, and managed by the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation. Due to the frustration of external debt burden and dwindling performance of the sector, however, the government decided to privatize the sugar sector. This made the sector the first among the “large” state-owned enterprises to set for privatization. However, the initiative was pending to date.The purpose of this study was to examine the factors that have been affecting the initiative of sugar factories privatization in Ethiopia. The study answered the question, “what factors are affecting the sugar sector privatization in Ethiopia?”

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Concept and Forms of Privatization

2.1.1. The Concept of Privatization

- The term privatization is defined in different ways. In public management spectrum, for instance, any organizational and operational measures government take to bring efficiency are identified as a privatization measure [10]. In such contexts activities such as the public pays charges for the service a public enterprise provides, private companies are financed by the government for providing certain services for the public, public corporations established by law operate as private enterprises under the market doctrine, and liberalization of some industries by removing government regulation is conceived as an example of privatization [11]. However, all these forms indicate state transfers its control to the private, but still ownership remains at the hand of the state. Nevertheless, privatization in its narrow context implies the transferring government assets to the hands of private sectors fully or partially [4]. According to [12], privatization is the process and program of divesting government ownership in state-owned enterprises to the private sector and the investing public. Moreover, [13] argues privatization involves “changes in income flows between groups” besides the transfer of ownership. Generally, privatization in this dissertation is used to refer to the transfer of ownership of the sugar factories with or without any share of the government.

2.1.2. Forms of Privatization

- Privatization may take different forms. Some of the forms include “negotiated sale to certain private firms, management buy-out, and public offering through Initial Public Offering-IPO” [11].Privatization is not a uniform process, not least because of its politicized nature. Comparisons among countries are also made difficult by the differences in methods used to privatize. Among the methods used to privatize companies have been direct sale, usually via tender or direct negotiation, public offer (via the stock exchange), joint venture, lease, for example of hotels in national parks, sale of assets, and liquidation [14]. Moreover, governments have tended to bunch up their sales, for example selling hotels, banks or textile companies at about the same time.On the other hand [11] presented five different policy alternatives governments may take when planning a privatization program. One is remaining status quo in which an enterprise would remain as a public entity wholly owned by the government but would be operated by commercialized management. Merger of another related enterprise the second option. In this case, two wholly government-owned corporations merge into a single organization. The third alternative is securitization, a form of raising capital from the market without transfer of government ownership of assets. Fourth, assets may be fully privatized. This is a full transfer of government ownership to the private sector through negotiated sale to selected private firms and management buyout. Finally, partial privatization may be opted. This involves partial transfer of government ownership to the private sector through the public offering or franchising only part of the railway operation. Yet it should be noted that the decision of choosing from the given alternatives depends on the goal of the privatization program.

2.2. Why Privatization of Sugar Industry

- Global trend shows the sugar industry in many nations that dominate the current production and distribution market had been owned by the states of nations themselves. Tracing back to 1960s to 80s, [15] discussed how the governments of the US, Brazil, Japan, Australia, and Thailand used to control the production and market of sugar, and asserted that the world sugar price would have perhaps been too expensive unless there had been an intervention.Later in the 1990s, however, the effort of freeing domestic sugar markets came into realization in the US. One of the largest and most efficient sugar producers in the world, Brazil, for instance, took the measure of reducing and then eliminating the export tax on sugar and deregulating the market in 1996 [16]. In Australia, reforms that attracted new investments took place in 1997 [17]. The scenario is almost the same in different countries. Concerning the reasons behind the urge to reform in the ownership structure of sugar factories is, however, the economic reform agenda- either consequence of changing regimes or the burden of financial crisis which forced the nations to recruit lenders policy [18]. In other words, rearrangement of policies, both social and economic, of the predecessor is often considered as a means to lobby the citizens of many countries to trust the newcomer though failure to successfully execute the new policy change cannot be completely free from the influence of traditions and practices. In favour of this, for instance, [19] government intervention in the sugar industry has been rooted in the trade arrangements nations had established with trade unions in different times and innate fear of the authorities suspecting conflict of interests may arise between suppliers and producers or distributors.

2.3. Factors Determining the Success of Privatization Programs

- Since privatization has been a common practice globally since the early 1980s, researchers have come with success and failure stories of privatization in different nations. Based on international experiences, [20] listed out numerous conditions success of privatizations depends on, such as a promising economy with adequate national savings, a healthy banking system, a viable capital market; political commitment to withstand the resistance from interest groups and bureaucrats; high level of public acceptance; transactional factors like financial expertise, permissible collective agreements with labour union and a capacity to create legislation to facilitate privatization; and an adequate regulatory framework.In their analysis of competitive sectors’ privation, [21] brought to light the following factors as determinants of privatization success: strong political commitment combined with wider public understanding and support for the process; creation of competitive markets-removal of entry and exit barriers, financial sector reforms that create commercially oriented banking systems, effective regulatory framework-to reinforce the benefits of private ownership; transparency in the privatization process and measures to mitigate the social and environmental impact.The success of privatization also depends on a nation’s economic situation. Concerning this, [22] emphasized on a good economic environment for the successful accomplishment of a privatization plan. In other words, an open and free economy, open markets, no subsidies, and liberalization in all sectors of the economy are of critical importance. Moreover, [23] found out good financial climate, a stable currency, appropriate laws for investments, tax incentives, and in general, an environment of economic growth as critical factors for affecting the program.In the research aimed at identifying the factors affecting the success of privatization in the Hong Kong context, [11] summarized success factors into three: strong political leadership, promising financial environment, and well-established regulatory framework (p. 21). Besides strong political leadership, promising financial environment, and effective regulatory mechanism in the pioneering Britain, [11] also added creation of effective product market, prioritizing the privatization exercises, putting the state-owned poor performers onto the priority list for privatization, defusing opposition, and the right policy choice to contribute for success in the exemplary privatization program of Mrs. Margaret Thatcher in 1970s (p.26-29). In explaining the success of Taiwan’s privatization, [11] further added four new success factors: the creation of a sufficient and clear legal basis for the government to conduct privatization; the well-scheduled privatization program; holding of residual shares; and protection of employees’ rights and benefits. These factors can develop the confidence of the public on the state while minimizes potential opposition from the interest groups.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Setting

- This research was conducted in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, one of the countries in the African continent. The case of the Sugar Sector was the primary focus of the dissertation. Ethiopian Sugar Corporation, a federal government entity in charge of administering the sector, was the heart of this study.

3.2. Research Design

- A mixed research design, which combines both qualitative and quantitative data, was used. This design was preferred because, as [24] noted, it enables to gain a comprehensive view of all aspects of an issue through combining the “strengths of both qualitative and quantitative designs in a single study” (p.203). Moreover, the research was a description of the state of affairs as it existed at the time of study [25] (p.2).

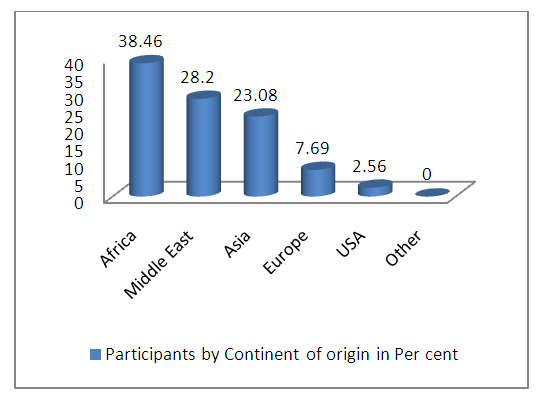

3.3. Target Population

- This study targeted primarily on the private investors who once showed interest to buy the Ethiopian sugar factories. Until 2017, 28 investor groups (20 from international and 8 from Ethiopian origin) were interested and thus registered to enter into privatization deal in the sugar sector. Key stakeholders whose roles were defined in the sugar sector laws also took part in the study.

3.4. Sampling and Sample Size

- A non-probability sampling method was used to select participants of this study as non-probability sampling is used when one has a very small population to work with. Thus, a purposive sampling method was employed to select participants from primary data sources. In this way, first, a total of 84 participants (3 individuals from each group) were purposively selected. Employing the same sampling technique, 13 participants were selected from the key stakeholders.

3.5. Tools of Data Collection and Measurement

- Data were collected by using a close-ended, 5 point Likert type questionnaire and Focus Group Discussion (FGD). The questionnaire contained 30 independent items, based on a scale from “Very High” to “Very Low,” that sought participants’ opinion about the potential issues which affect the sugar sector privatization process. According to [26], Likert scales enable to identify feelings and opinions. Meanwhile, FGD was carried out based on semi-structured questions which were assumed to generate ideas about the factors determining the sugar sector privatization initiative. Two rounds of group discussions, each lasting for 30 minutes, were held on.

3.6. Method of Data Analysis

- A mixed method was used for data analysis [24]. The categories used in the Likert type questionnaire were Very High, High, Moderate, Low, and Very Low. Then, the values from 1 to 5 were assigned for these scales in the respective order. SPSS (version 21) was employed to work out percentages for each statement (as [27] suggested). In line to [27], however, the two outside categories: "Very High" and "High" on one hand and "Low" and "Very Low" on the other hand were combined to determine which factors in the main categories needed attention as these had been affecting the privatization process. Moreover, the median and mode were used as measures of central tendency. The FGD data were categorized, coded and grouped concurrently during data collection. Four categories, namely legal/institutional, political, socio-economic and market, emerged at this stage. Each type of data was first analyzed separately, and then mixed during discussion of the result.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

- All possible ethical issues were given consideration in the course of this study. The names of data sources were kept anonymous during data analysis. They were informed that their participation would be based on their free will, and so each of the participants signed a consent form.

4. Analysis, Result and Discussion

4.1. Summary of Participants’ Demography

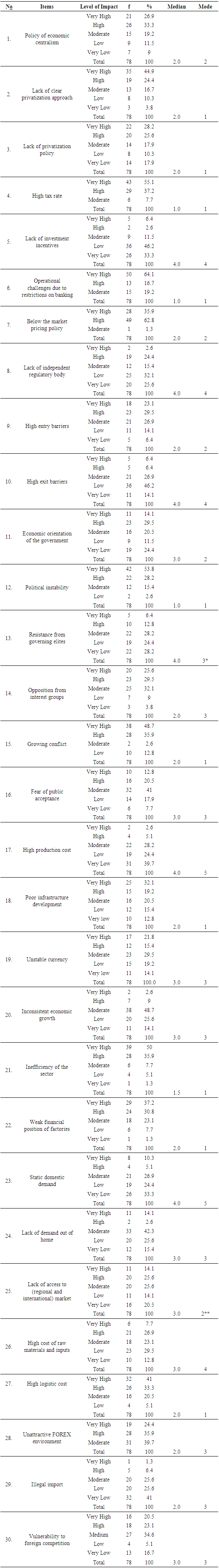

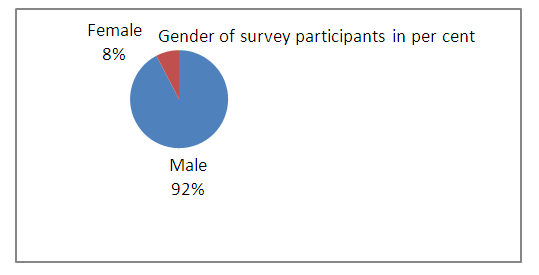

- Among 84 questionnaires distributed, 78 returned (92.9%). Majority of the respondents (92.31%) were male whereas only 7.69 percent were female (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Gender of participants |

| Figure 2. Country of origin of investor groups |

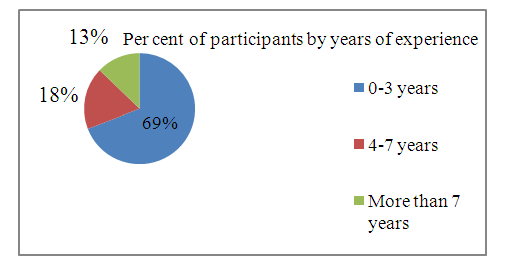

| Figure 3. Participants experience in the sugar sector investment |

4.2. Factors Affecting the Sugar Sector Privatization

- In line to the research objectives and literature reviews, four themes emerged during data analysis. The result of both quantitative and qualitative data was mixed and discussed altogether. Further, related literature was consulted to consolidate the discussion and to validate the findings.

4.2.1. Legal and Institutional Factors

- Among the responses of 10 items in the legal and institutional factors’ category, high tax rate (92.3%), operational challenges due to restrictions on banking (80.8%), and pricing policy (98.7%) were found to have very high impact on the sugar sector privatization process in Ethiopia (Table 1, Appendix I). These responses fell above the median (2.0). On the other half of the median, lack of clear privatization approach (69.2%), policy of economic centralism (60.3%), high entry barrier (52.6%), and lack of privatization policy for the sugar sector (53.8%) were identified to have a high impact on the success of sugar sector privatization process. The responses of FGD participants and inferences of the literature review confirmed these findings. As noted in review literature [32], sugar development levy and excise tax on sugar were two major taxes/levies currently impacting the profitability of the Sugar Industry. Levy was imposed on sugar products and effectively paid for by the end consumer. The excise tax on the cost of production of sugar operations charged 33% of the direct production cost, and payable on sales of sugar both to the domestic and export markets. The issue of pricing policy was also supported during the discussion. The sugar selling price was set by the government itself and the ‘official’ price was 20% lower than the next lowest price in the region [33]. For private investors, however, this price would never result in an insufficient return. Ethiopia has not yet allowed for foreign commercial banks to operate in the country [34], and the local banks were under the state control. While there were foreign currencies in Ethiopia, lack of stock exchange and capital market, and international banking were challenges for investors either to get currency or to take its profit to the home country. Similarly, it was challenging for foreign employees to remit their wages to home. For the specific sugar sector privatization, the discussion participants confirmed the development of policies and guidelines was “underway,” but privatization initiative embarked in before few years. While splitting the sectors domestic and international investors can invest in Ethiopia, the economic policy in Ethiopia had no vivid statement on whether a local private investor could engage in a joint-venture undertaking with a foreign investor or not. [35] stated this as a “polite way of discouraging foreign private capital investment in Ethiopia (p.25).” Moreover, as the Ethiopian sugar sector privatization call had no pre-established policy ground, evidence was not available on what model and scheme would the government follow. Expecting the suggestion from the interested investors themselves left the potential investors uncertain even if the government would no doubt be pleased with whatever proposal they might come with. Moreover, as the sugar projects differ in the level of performance, capacity, financial wellbeing, etc. generic call for sale brought no result, because researches revealed that private investors can less likely enter into a deal to buy poorly performing, overstaffed or larger ones [36]. Thus lack of clear policy was a factor affecting the sugar sector privatization process. Nevertheless, lack of independent regulatory body (57.7%), high exit barrier (60.3%), and lack of investment incentives (79.5%) were ranked to have very low impact in the survey. Moreover, the discussion did not bring evidences on the impact of these issues.

4.2.2. Political Factors

- Political instability (82.0%), growing conflict (84.6%), opposition from interest groups (55.1%), and economic orientation of the government (43.6%) were identified as the most determinant political factors (Table 4.1). All of these items fell above the median in which 3 (Moderate) was the mode. While fear of public acceptance (41.0%) had a moderate impact, resistance from the governing elites (consolidated sum for Very Low = 52.6%) was the least impacting factor.Ethiopian government gave protection for private property as guaranteed by constitution [37] and investment code besides being a member of the institution which issues guarantee against non-commercial risks to enterprises that invest in signatory countries, the FGD participants refused to rely on such policies amid the country’s political instability in the recent years. Noting the State of Emergency was in effect in some parts of the country, political instability was taken as a major risk factor for not only the business but also the life of individuals. With regard to political risk and government stability, [38] argued that privatization has been more likely in more stable regimes. This was because less stable governments were not willing to accept the political risk involved in a large privatization. When the government was stable, it would be easier for the ruling party to gain consent for privatization policy decisions and the executive enjoys greater stability.Unlike [39] findings showing power imbalance between decision-makers at either the legislative or executive levels, opposition from political parties was less likely to impact investor’s decision. Moreover, less stable governments may lack the ability to effectively enforce property and contractual rights which in turn are necessary to implement privatization [40]. However, the impact of “opposition from interest groups” and “fear of public acceptance” were found to get insignificant support from the FGD data. As noted during the discussion, the current government in Ethiopia has been dominated by a single party. Moreover, the public, particularly the local public, could oppose depending on the new policy direction if it would affect their interest. Thus, opposition would be unlikely in such cases. On the other hand, the investors fear that the government could not successfully make or enforce laws of private investment, property protection when it remained weak. Hence, political stability can determine its ability to carry out its declared programs, and so taken as a serious factor.

4.2.3. Socio-economic Factors

- Among the responses in the socio-economic category, the inefficiency of the sugar sector (with the consolidated sum of very high and high=85.9%), poor infrastructure development (51.3%), and unstable currency (37.2%) were factors the analysis revealed as major determinants (Table 4.1). The median and mode of the items in this category were 3 (moderate). These findings confirmed to the findings of researches by [41], which revealed the success of privatization materializes when governments sequence privatizations strategically, often leading the most profitable firms to be privatized first, and firms with a lower wage bill are likely to be privatized early. In the case of the Ethiopian sugar sector, however, the sugar enterprises had been performing less efficiently compared to other state-owned firms and this was a reason government wanted to sell out the enterprises. Therefore, the current financial stand of the sugar factories was one of the factors which discouraged private sector investment. In line with this, [42] showed that many state-owned enterprises exhibit poor financial performance, possibly because they were used to make politically-motivated loans. Thus privatization is likely when the sector is loss-making and it is less efficient [39]. In terms of high infrastructure demand in localities, participants of discussion confirmed it had been among the major determinant factors. On the other hand, the inconsistency of national economic growth (48.7%) was identified to affect the process at a moderate level; however, high production cost (64.1% ranked its impact as very low) was not supported as impacting factors in the FGD. This result confirmed to [33] that it revealed Ethiopia was a low-cost producer due to the very high productivity of cane per unit area and cheaper labour force.

4.2.4. Market Factors

- High logistic cost (74.4%), weak financial position of factories (67.9%), unattractive FOREX environment (60.3%), and vulnerability to foreign competition (43.6%) were identified as the topmost serious market-related factors affecting the sugar sector privatization based on the consolidated sum of the scale (Table 4.1). It was confirmed by FGD that the sugar factories were scattered in different parts of the country and so not only transportation to limited port outlets but also to the national central market was causing high cost. Moreover, the fact that the sugar factories were under the burden of loan and interest, and high demand for subsidy from government implied the sector was less attractive to investors. As learned from the literature review 10 of the 13 sugar projects offered for sale were under different levels of development, because these projects were being financed by the loan gained from different countries [43]. Since the interested investor had to value the project at the current stage of development, and then negotiate on not only the sale price but also how the loan would be paid before entering into any form of privatization deal, the process would require a longer time than the government expected. As noted during the Discussion, this made the deal ‘hectic,’ and thus the sector became unattractive. Causes for FOREX shortage embraced high reliance on imports and inflation which government instrumented to generate liquidity [44]. The investors and expatriate employees cannot easily find currency to remit. This made the FOREX environment unattractive. Further, the sector’s vulnerability to foreign competition was the factor that affected the process of privatization. These responses were also supported by FGD and literature [44]. Lack of access to (regional and international) markets (39.7%) was identified to have a moderate impact. This is because of limited port outlets on one hand and logistic cost as confirmed in the above section on the other hand. Finally, the other factors – the high cost of raw materials and inputs (42.3%), illegal import (51.3%), lack of demand out of home (41.0%), and static domestic demand (57.7%) - were found to have very low impact. Each of these items fell exactly below the median. As noted during the discussion, state-owned farms were yielding adequate sugarcane through currency shortage used to cause delays in the purchase of imported chemicals. Sugar product demand had been high both in the domestic and regional markets [33]. Moreover, unofficial sugar import was mainly encouraged by the shortage of the product in the national market, and a high tax on import. Thus, both literature and discussion confirmed the result of survey data analysis.

5. Conclusions, Limitation and Future Research

5.1. Conclusions

- This study found out the determinant factors relating to the legal and institutional arrangements governing the sugar sector, political situation, socio-economic and market environment in Ethiopia, and financial status of the sugar sector itself. Among the legal and institutional factors, high tax rate, operational challenges due to restrictions on the banking sector, pricing policy were found to have very high impact. Moreover, lack of a clear privatization approach and indicative policy for sugar sector development, the policy of economic centralism, high entry barrier, and lack of privatization policy of this specific sector had an impact on the success of sugar sector privatization process. In relation to political factors, political instability, growing conflict, opposition from interest groups, fear of public acceptance, and economic orientation of the government were identified as the most significant factors determining the sugar sector privatization process. While fear of public acceptance was marked to have a moderate impact on the privatization process, the impact of resistance from the governing elites was found to have a very low impact among the political factors.Among the socio-economic factors, the inefficiency of the sugar sector, poor infrastructure development, and unstable currency were identified to have a very high impact on the sugar sector privatization process. Besides, high production cost was identified as a factor with very low impact. From market and financial aspects, high logistic cost, the weak financial position of the sugar enterprises, unattractive FOREX environment, vulnerability to the foreign competition, and lack of access to market had a significant impact on the sugar sector privatization process. Among the factors checked for impacting the privatization process, however, the high cost of inputs, illegal import, and static domestic demand were identified to have the least impact. While the Ethiopia government decided to privatize one of the giant enterprises under its ownership, and willing to provide incentives for the private investors, the current study affirmed the privatization initiative had strengths such as initial consultations to avail legal frameworks, dialogue with potential investors, deals with financiers, and process transparency. Yet, delay in creating an enabling legal, financial, and market along with other socio-economic and political factors put the prospects of sugar sector privatization under question. Lack of adequate industry data, loops in devising strategies to combat potential opposition from interest groups, absence of roadmap about how issues of ownership would transfer, either fully or partially, can be handled made the process ambiguous. Consequently, the success of the years’ long sugar sector privatization initiative yet remained amid uncertainty. Thus, it is too soon to confidently conclude the initiative would succeed unless future researches prove the Ethiopian government took into account the issues identified in this dissertation and puts into effect the suggestions outlined in the recommendations section below.

5.2. Limitation and Future Research

- The current article has a few limitations. The study framework covers a few issues relating to the four main factors; however, there may be more factors that can affect the privatization process. In this article, the participants were private investors and key stakeholders from government and private agencies at the federal level in the country. Involving employees of the sugar projects and local administrations might in the future result in better results. Therefore, future researchers can include more issues and include participants from all interest groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- First, I am highly indebted to thank the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation management members for the moral support each of them provided me in the course of this study.My heartfelt thanks also goes to my wife, Mrs. Tigist Desalegn, and my children Yodahe Abraham, Kurubel Abraham, and Benyas Abraham for their diligent support and devotion without which I would not succeed in this study and in my life in general.Finally, I am very grateful to Mr. Mengistu Lamaro for his assistance in SPSS, proof-reading and write-up.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML