-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

p-ISSN: 2168-457X e-ISSN: 2168-4588

2020; 8(1): 1-7

doi:10.5923/j.m2economics.20200801.01

Influence of Strategic Leadership Style on Partnerships Implementation in a Medical Research Organization in Kenya: A Case Study

George Kirigi

Doctoral Candidate, Pan Africa Christian University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: George Kirigi , Doctoral Candidate, Pan Africa Christian University, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Partnership in leadership is a phenomenon with little research attention, until now. Partnerships are high on the international development agenda typically as goal 17 of global sustainable goal development agenda. The regional and intergovernmental research collaborators and NGOs are also represented. But public–private partnerships implementation lacks balanced collaborative leadership as the best pathway to improve in particular health outcomes. It is not clear in the medical research corporations on whether empirical data on partnerships reach organizational employees to utilize in building their case for sustainable futures. To gain more knowledge, this study used case study approach to obtain primary data and analyzed key informants’ feedbacks on partnerships processes on the basis of their positions and relation to partnerships within their own organization. Responsive approaches of measurements prioritize multiple partnerships strategy into two types: performance of partnership itself and outcome performance. The ideal leaders of this strategic direction in organizational change in respect to medical research institutes ought to be a collaboration of a symphony of specialized experts playing in harmony, the so-called the symphonic C-suite instead of a cacophony of experts who sound great alone, but not together. An organization need consideration of partner selection, portfolio management of partners, negotiation skills, execution of diversity and exit arrangements are important considerations. The success or failure of partnerships will depend on how the managers understand partnership as the new leadership for implementation of strategy in organizations. Findings have practical implications for managers and researchers.

Keywords: Strategic leadership style, Collaborative leadership, Partnership, Medical research organization

Cite this paper: George Kirigi , Influence of Strategic Leadership Style on Partnerships Implementation in a Medical Research Organization in Kenya: A Case Study, Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.5923/j.m2economics.20200801.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Partnership in leadership is a phenomenon with little research attention, until now. Recent and significant number of literatures attempted to guide on best practices for partnerships between researchers and collaborator agencies (Winterford, 2017). But public–private partnerships implementation lacks balanced collaborative leadership as the best pathway to improve in particular health outcomes (Nyström, Karltun, Keller, & Gäre, 2018). There is little evidence in medical research corporations on whether empirical data on partnerships reach organizational employees to utilize in building their case for sustainable futures. An interdisciplinary approach to investigate collaborative and partnership research has the potential to facilitate a strong climate for knowledge transfer that can implement research translation to researcher practice. Partnerships are high on the international development agenda typically as goal 17 of global sustainable goal development agenda (Partnership for Sustainable Development Goals, 2015). The regional and intergovernmental research collaborators and NGOs are also represented. But public–private partnerships implementation lacks balanced collaborative leadership as the best pathway to improve in particular health outcomes (Mshana, Aagard, Cullen, & Tschida, 2018). In line with knowledge brokering (Lomas, 2007; Knight, & Lyall, 2013), there is little evidence in medical research corporations on whether empirical data on partnerships reach layered organizational employees to utilize in building their case to contribute to sustainable futures. Strategic communications are crucial to promote partnership Leadership Synergy but yet understudied in medical research organizations in Kenya. To gain more knowledge this study used case study approach to obtain primary data and analyzed key informants’ experiences and thoughts on partnership processes on the basis of their positions and relation to partnerships within their own organizations. The last fifty years the world has seen an explosive multiplication of new international bodies for economic, social, political, health, and human rights issues (Ivanova, 2003). The growth of agreements and organizations has been unparalleled. The main focus for policymakers has been governance structures in order to reduce the overlap, fragmentation, and conflicts within the international environmental regime. It is believed that network partnership characteristics of commitment, equity, mutuality, and trust together with network behavior will vary by the degree of publicness but collectively contribute in a positive manner towards the performance of sustainability projects. Partnerships face complex challenges which are often approached through siloed solutions whether policy, markets, or social programs. But rarely are these attempts sufficient because the challenges faced are the result not of one policy, investment, or program, but of the interactions between them. Increasingly, interest in cross-sector collaboration is on the rise (Edmondson & Harvey, 2017). Research QuestionsThe research questions that had to be addressed:1) How do identified key informants qualitatively describe their leadership synergy on existing partnerships in a medical research organization?2) How do identified key informants qualitatively recount characteristics of their knowledge on existing partnerships processes in a medical research organization? General objective Describe the influence of Strategic Leadership Style on Partnerships Implementation in a Medical Research Organization in Kenya. Specific objectives1) examine key informants’ experiences on partnerships processes and synergy in a medical research organization.2) to critically evaluate key informants’ feedback and its implications for partnership leadership in a medical research organization.Statement of problemThere is little evidence in medical research corporations on whether empirical data on partnerships reach organizational employees to utilize in building their case for sustainable futures. An interdisciplinary approach to investigate collaborative and partnership research has the potential to facilitate a strong climate for knowledge transfer that can implement research translation to researcher practice. Collaboration and partnerships are two concepts used to describe the involvement of people and groups from different contexts and with different experiences, perspectives and agendas in research and development (Nyström, Karltun, Keller, & Gäre, 2018). Put in another way, collaboration as a process through which parties who see different aspects of a problem can constructively explore their differences and search for solutions that go beyond their own limited vision of what is possible. Partnerships are forging new relationships among industry, government, NGOs and other societal stakeholders and establishing new social values compatible with sustainability (Nyström, Karltun, Keller, & Gäre, 2018). It all matters to explore managers’ beliefs in practice and how they integrate their role and responsibilities in multiple partnerships for future state.Significance of the studyThis significance of the study is in the fact that partnerships are becoming more systematic and a critical way of tackling national and global problems. Effective leadership style in partnerships is crucial to initiate, direct, anticipate and sustain vision for the success of partnerships.

2. Literature Review

- On the one hand, International organizations are the traditional facilitators of collective action at the international and global level and provide a particularly interesting analytical lens for partnership arrangements. International organizations perform a range of roles in a partnership context such as; enabler, facilitator, supporter, or active participant and influence the shape, form, and function of the collaborative arrangements (Deloitte Global, 2018). On the other hand, the growth and institutionalization of partnerships is likely to impact the operation of international organizations and have substantive consequences on the architecture for global governance (Ivanova, 2003). Collaborative leadership theories emphasize working with groups inside and outside the organization (Van Wart, 2013). Collaborative leadership is considered the most popular and dynamic leadership theory because of its connection to collaborative or network governance studies (Quick & Feldman, 2014). Collaborative leadership theories belong to studies of relational or horizontal leadership. Van Wart (2013) explained that relational leadership emphasizes the process and contexts in leadership studies and elevates the importance of leadership oriented to enhancing partnerships among individuals or organizations. The direct and inevitable result of the great and growing volume and variety of mutual involvement is the multiplication of actual and potential points of friction. Thus, attention to multiple partnerships in collaborative science is a recent phenomenon in an organizational context in Kenya. In the early 2000s the Office of Research Integrity proposed that the collaborative science agenda comprised Research collaborations and issues that may arise from such collaborations. For example, setting ground rules early in the collaboration, that concerns authorship disputes and publication practices, conflict of interest and commitment, data acquisition, management, sharing and ownership, human participants protection, research involving animals, intellectual property rights, and the sharing of materials and information with internal and external collaborating scientists. Rhoten (2007) illustrated that the traditional model of big science is giving way to more contemporary school of thoughts of team science, which, in turn, is yielding to an emerging model that she calls networked science. In collaborative science literature, (Zerhouni, 2005) noted that some countries’ RoadMap have taken steps to advance the concept and include a framework that incorporate team science, networked science, informatics and innovative technologies. Moreover, Macrina (2005) explained that collaborative research and training programs integrate many specialized areas of science to solve complex problems by testing the same or similar hypotheses by different means which refer to interdisciplinary, translational approaches. It is interesting to note that academia, medical research organizations and industry are intertwined for many reasons. One reason is to accelerate advantages in knowledge creation, access to superior technologies from partners, critical mass for innovation. Gelijns and Their (2002) concluded that creative bridging of traditional divisions of labor (i.e. industry, universities, and medical research organizations) is vital to medical innovation.Conflict of interest can be arrested through the extent and frequency of contact between governments, people, and partners, the actual conflicts can be remarkably reduced (Parker, Zaragoza, & Hernández-Aguado, (2019). Inclusion is the act of including others in the processes of consideration, decision, and implementation. Inclusion goes beyond debate over who should be involved; it is also concerned with the means by which participants can take part, the agendas they are permitted to discuss, and the arrangements they make for those who cannot be present. Today's dominant styles have been termed responsive planning, which is far less regulatory than state-imposed strategies but nonetheless still accords importance to public policy goals, and partnership planning which combines the inclusionary aspects (Bloomfield, Collins, Fry, & Munton, 2001). Multiple partnerships as recent phenomenon in an organizational context and is increasingly seen as critical to the effective tackling of any global problem. In principle, governments have refashioned the state through the greater use of partnerships between previously under-connected market and civil interests Collaboration entails more than just economic or technological solutions to promote sustainability, but careful attention to leadership, decision-making, fairness and relationship management (Gray, 2011). In the same vein, Warren (2007) assertions put collaborative leadership as a necessary ingredient for partnerships. Warren’s illustrative view of collaborative leadership as the process to initiate, facilitate and sustain collaborative initiatives among stakeholders for addressing sustainability issues. Theoretically, the analysis of the leadership functions of this complex, longitudinal process is based on elements from the planning theory perspective, the leadership theory perspective, and the partnership theory perspective (Halkjelsvik, 2015). Formation of multiple partnerships within the same organization, it seems, is concept whose time has come. Kakabadse, Kakabadse, & Summers (2007) argued that the arrangements are supposed to deliver greater added value than government provision alone could achieve. Huxham and Vangen (2004) confirmed that even where partners have achieved their objectives or preliminary milestones, they often had to address challenges and signs of inertia for their successes to materialize. However, evident show that scholars contributing to the partnership discourse have pointed out the crucial role that appropriate leadership and social skill management play in overcoming challenges and achieving private-public partnership objectives. The trends on multiple business partnerships is mostly to avoid an exclusivity approach to business. Exclusivity is on the decline for many reasons. One reason is to avoid vulnerability. Practitioners of partnerships think it’s a developing partnership strategy in organizations and society in general. But that is valid in organizations as long as employees through understanding are able to assess and provide feedback to their managers. This study aims to explore the manager’s experiences and meaning of multiple partnerships and its impact on organizational outcomes. Case studies on the impact of multiple partnerships on strategic planning are limited. This research will attempt to build its case on the basis of filling the gap in literature about manager’s experiences and meaning of multiple partnerships and its consequences. The findings of the research are to leverage managers knowledge and leadership situation to inform leadership strategy in planning under organizational context. All and all, scholars have emphasized the need for the partners to develop a shared leadership by creating a shared vision backed with shared values and interpersonal and personal relationships (Saz-Carranza & Ospina, 2011). Pursuing this further, these scholars stress the importance of regular interaction and trust-building activities to develop cross-sectoral and cross-cultural understanding (Le Ber & Branzei, 2010), as well as the leadership capacities of individual boundary spanners, who bridge the gaps between the different partner organizations (Waddock, 2010). Partnerships provide institutions and individuals in lower income countries with many benefits, but there are also potential pitfalls, particularly with north–south partnerships. Since majority of these partnerships are compartmentalized. They are not institution wide. The southern researchers working vertically with northern partners get isolated from other researchers in their own institution or national networks. This risks fragmentation at a time when greater cohesion is needed. Power imbalance between northern and southern institutions in deciding the research agenda, managing decisions, and access to funding. Ultimately, the need to consult with multiple partners may lead to delays in decision making and increasingly complex team management. (Easterbrook, 2011).Two traditional forms of governance have dominated world affairs until recently: national governance through governmental regulation and international governance through collective action facilitated by international organizations and international regimes. One the one hand, governance is critical to partnerships. On the other hand, collaboration is central to partnerships. Brown, Kellam, Kaupert, Muthen, Wang, & Muthen (2012) considered collaboration as a process through which parties who see different aspects of a problem can constructively explore their differences and search for solutions that go beyond their own limited vision of what is possible. Collaboration implies interdependence among stakeholders, constructive handling of differences, joint ownership of decisions and collective responsibility of outcomes. In healthcare organizational environments partners take the shape of mandated or emergent (Kamya et al, 2017). Partnerships forge new relationships among industry, government, NGOs and other societal stakeholders and establishing new social values compatible with sustainability (Nyström, Karltun, Keller, & Gäre, 2018). Collaboration requires willingness to resolve conflict through best practices such as dialogue, mediation, consensus and collaboration among relevant stakeholders. Additionally, Warren (2007) noted that one of the primary factors that influences the nature of collaboration is whether or not participants hold a shared vision concerning the nature of a problem. Warren contested that collaborative leaders must focus on processes rather than outcomes. In other words, leaders must design and implement collaborative initiatives that are sustained through credibility, openness, trust and transparency. However, because collaborative leadership requires a change from traditional hierarchical forms of leadership, various obstacles can impede the practice. Winterford (2017) describes the paradox facing collaborative leaders in the implementation of social consensus and collaboration within firms by indicating that the most fundamental is the need to use competitive rhetoric to build internal cooperative networks. In this paper, the essential focus is on strategic leadership processes as processes in which influential acts of organizing contribute to the structuring of interactions and relationships, activities and sentiments; processes in which definitions of social order are negotiated, found acceptable, implemented and renegotiated; processes in which interdependencies are organized in ways which, to a greater or lesser degree, promote the values and interests of the social order. In a sense, leadership can be seen as a certain kind of organizing activity: for this reason, leadership is central to the dynamics of organization (Mumford, Campion, & Morgeson, 2007). Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff (2004) noted that mutuality partnership is a key conceptual feature. Haque (2004) asserted that organizational identity that is described as maintenance of each partner’s own identity, beliefs and values. Overall, Klijn, & Teisman (2003) noted shared responsibility for a product and shared resources, risk, costs and benefits between the government and private partners. In reality though, responsibility for the provision of public services may be fully shifted to the private sector.A community partnership face challenge in the implementation of its collaborative initiatives. The partnership fabric is affected by external factors such as; external market and regulation factors beyond the control of the partnership, scarce local community resources to support efforts, the scope and intensity of tasks associated with an initiative, an expanded partnership to include new members, and the balance of work between partners and paid partnership staff. All in all, it is illustrative to note that leadership emerge as a consistent predictor of its success in partnership. Moreover, Bazzoli et al. (2003) suggested that members perceive partnerships with effective or ethical leadership positively. In the same vein, Alexander et al. (2003) argued that programs that were able to provide an account to their community had long term impact. However, Hasnain-Wynia et al. (2003) observed that a surprising number of partnerships with wide range of representativeness of member promised no advantage. The next question that will be addressed is how organizational structure impact on the governance of partnerships.Top-down or Bottom- up organization in general refer to as a cultural identifiable entity, or unit of analysis, which exists independently of participants’ activities and sentiments. Hierarchical knowledge can also be a barrier to effective partnership leadership especially when command and control opinions strongly emerge. It is usual to find some minimal degree of unity is assumed to follow from shared cognitions, shared goals, and or shared values. In addition, the entity is typically assumed to be held together by organization structures and treated as independent of participants. This approach is referred to here as top-down in the sense that the model of organization (top) is separate from, and causally dominant to the model of person (bottom). Warren (2007) argued that a top-down approach either for pragmatic reasons, or other reasons organization is treated as not merely greater than the sum of its parts, but so superior that it is effectively divorced from the influence of its parts. In other words, the approach results in a sharp divide between person and organization such that the agent, responsible for the latter, is left untheorized as an agent. For this reason, it is perhaps not surprising that relations between leadership and organization have been largely neglected: the definition of the latter has made it independent of, and incommensurate with leadership (Warren (2007). A bottom-up approach, in contrast, fail to emphasizes the whole part of organization (Warren, 2007). Of course, bottom-up recognizes persons as agents in the achievement of organization. In this way, a bottom-up approach has the advantage of shifting emphasis away from the assumption of a relatively status quo (organization), to the processes in which organizing is manifest which is an inherently dynamic perspective. Therefore, a bottom-up approach renders amenable to analysis, leadership acts and processes as special kinds of organizing: organizing which reflects, and consistently effects, other parts of organization. In comparison, bottom-up makes leadership intrinsic to organization, rather than a mere epiphenomenon as in a top-down perspective and it is basic concept why organizing is advocated. When the condition of being organized is emphasized, this focuses attention on organizational context features in a way which implies they exist independently of the interactions and sense-making of participants. This has been referred to as a physicalist approach (Schwarz, 2002). For example, it is managers who have typically been requested to describe organizational structures as the prescribed framework of organization (Rothaermel, 2016). Organization can be metaphorical and managers can only give that much as a description of an organization. Besides, leaders have argued in regard to organizational structures, that there is social constructions of organizing. This may be understood through examination of relationships, interdependencies, influence status, and social order, and could include attention to centralization, standardization, and so on. Such an approach recognized that, through their organizing activities, participants assemble ongoing interdependent action into sensible sequences that generate sensible outcomes (Rothaermel, 2016). There is need to study organizing activities in which participants negotiate and enact a sense of social order that is, an adequate guide to the use of knowledge and the conduct of human affairs (Nyström, Karltun, Keller, & Gäre, 2018). It is important to be clear that organizing is advocated as the focus of analysis, whether or not located in relation to an organization. For this reason, attention is directed to observed activities, acts, contacts and relationships. It has long been apparent in the popular assumption that participants share goals and/or values, and that their activities should reflect this. Moreover, Nyström, Karltun, Keller, & Gäre (2018) argued and defended that to maximize the effect and to fulfill mission which is to promote and foster research with the aim of improving human health, their reasoned judgment was that they were to be strategic in making their funding policies. Additionally, to realize this effectively, their judgement was that their organization needed to provide leadership, while acting in partnership with governments, industry and the biomedical community.

3. Methods and Materials

- Study designA case study conducted as cross-sectional design using structured questionnaires.Study population and SiteUnity of analysis consisted KEMRI workers based on identified unity of observation in Nairobi city County, Kenya.SamplingThe three key informants constituted the desired sample on the basis of their current actual work positions and returned three completed validate questionnaires in line with Partnership Self-Assessment Tool (2002).Sample sizeThe study had three key informants as target respondents in a chosen organization. Data CollectionEthical consideration incorporated voluntariness when inviting Key informants. The instrument of data collection was a predetermined structured questionnaire in order to obtain data from individuals and consists of a set of open and closed questions. In this paper, reliability of a construct or variable refers to its constancy or stability in the questionnaire as medium. Data AnalysisData had no personal identifiers of respondents except the number that can be easily be identified only by the researcher. Hsieh and Shannon (2005) proposed that Content Analysis is research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns. In the same way, Krippendorf (2013) illustrated that data can be categorized, themes coded for qualitative sematic data. The ultimate meaningful synthesis (inferences/interpretations) will be on the basis of codes and categories for the data. The entire sequence of this procedure will be as follows; defining unit(theme) of analysis, defining subcategories and codes based on the study approach and objectives (qualitative properties, primary or secondary data, inductive or deductive), pretesting for consistency, Content Analysis fits well to the handling of context-sensitive information and can be done both manually (Heisig, 2009) and automatically (Ribière & Walter, 2013) to discover prevailing research topics or trends in the observed analysis unit. To ensure validity, qualitative studies are validated through trustworthiness and rigor (Leung, 2015). This is dependent on truth value, consistency/neutrality and applicability (Noble & Smith, 2015).ProcedureAll data on the questionnaires had no identifiers of the respondents. Since all three respondents returned, the response rate was successful. Main themes were identified and a nonpredetermined coding, content analysis and interpretation of data commenced when all completed questionnaires were returned.

4. Results and Discussions

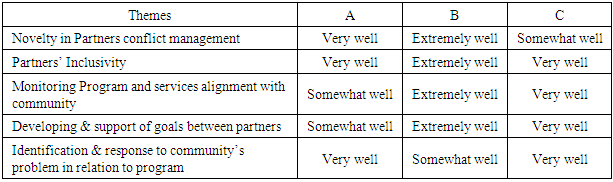

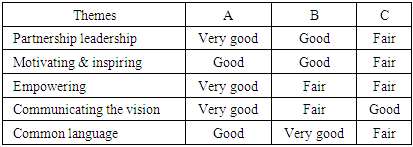

- The significance of the results reflects the research questions restated as previous. Themes and patterns have also been treated to have a meaningful qualitative bearing as below (Table 1 & 2);

|

|

5. Conclusions

- To conclude, understanding characteristics of partnerships leadership synergy and processes in KEMRI require research attention for effect performance. Only a few people have access to this information to conduct useful research on partnership knowledge. Findings of this study have implication for managers. Further research in a detailed design is proposed in future.

Limitations of the Study

- This is an exploratory case study limited to one organization business and, as such, findings may not be generalizable but transferable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The Director of KEMRI permission to publish this work is much appreciated. I am grateful to the key informants for their knowledgeable information. I am also indebted to Dr. Barnabe Anzuruni Msabah, of Pan Africa Christian University, for his technical assistance.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML