Qing Hu1, 2

1Department of Economics, Kushiro Public University of Economics, Kushiro, Japan

2Research Fellow, Graduate School of Economics, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan

Correspondence to: Qing Hu, Department of Economics, Kushiro Public University of Economics, Kushiro, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Partial cross ownership is a widely observed activity in many industries. The conventional wisdom shows that partial cross ownership weakens the competition in Cournot competition, thus it increases the firms’ total profits. We investigate whether this conventional wisdom still holds in network industries. We find that this conventional wisdom reverses when the network effect is relatively intense. This finding is very meaningful for the firms in network industries to reconsider the problem of partial cross ownership. We also examine the partial cross ownership problems in a mixed duopoly market.

Keywords:

Network externality, Partial cross ownership, Cournot duopoly

Cite this paper: Qing Hu, Network Externalities and Cross Ownership, Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2018, pp. 50-53. doi: 10.5923/j.m2economics.20180602.03.

1. Introduction

There are many cases where one firm owns its rival’s partial equity but not participate in the rival’s decision making. Such kind of partial cross ownership (PCO) is widely observed in many industries. For instance, in the Japanese steel industry, Gilo and Spiegel (2003) reported that Japan’s second largest steel producer, Kawasaki steel company, acquired a minority stake in Korea Dongkuk steel company and held a 40 percentage stake in American steel producer, Armco. And in the automobile industry, Renault acquired a 36.8 stake in Nisson Motor in 1999 (see Barcena-Ruiz and Oliazola, 2007). And as pointed by Gilo and Spiegel (2006), Microsoft acquired in August 1997 approximately 7 percentage of the nonvoting stock of Apple, which was the historic Microsoft’s rival in the PC market. The conventional wisdom shows that PCO weakens the competition in Cournot competition, thus it increases the firms’ total profits. Fanti (2013) pointed out that this anti-competition effect of PCO is maximal when the products are homogeneous. This paper reexamines the above conventional wisdom whether an increase of the level of PCO increases the firms’ profits still remains true in network industries. As the fast development of network industries in recent years such as telecommunication industries, there are many researches about how network externalities change the results under normal product market (see Katz and Shapiro, 1985; Pal, 2014; Fanti and Buccella, 2016; Pal and Scrimitore, 2016). However, there is a lack of research about the problem of PCO in network industries. This paper aims to fill this gap in the literature. We find that the conventional wisdom reverses under network effects, that is, an increase of the level of PCO may reduce the firms’ profits when network effect is relatively intense. This result is very meaningful for the firms in network industries to reconsider the problem of PCO. The reminder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the model. Section 3 discusses the equilibrium outcomes. Section 4 presents an extension. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study.

2. The Model

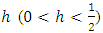

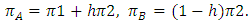

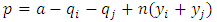

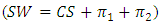

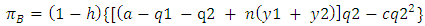

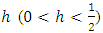

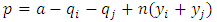

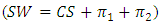

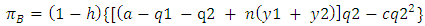

We consider an industry consisting of two firms, 1 and 2, which produce homogeneous network goods. There are two shareholders, A and B. Firm 1 is solely owned by shareholder A while firm 2 is jointly owned by the two shareholders. Shareholder B has the majority shares of firm 2 and thus controls firm 2. We denote by  the fraction of shares that shareholder A has in firm 2. The shareholders A and B are assumed to maximize their total profits

the fraction of shares that shareholder A has in firm 2. The shareholders A and B are assumed to maximize their total profits  and

and  , respectively as following:

, respectively as following:  | (1) |

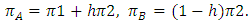

Following the established literature (see, e.g, Pal, 2014; Fanti and Buccella, 2016; Pal and Scrimitore, 2016), we assume that the representative consumer utility function is given by:  | (2) |

with  Then, the inverse demand function can be derived as following:

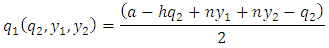

Then, the inverse demand function can be derived as following:  | (3) |

where  is a parameter that captures the size of the market.

is a parameter that captures the size of the market.  denotes the price of goods,

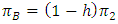

denotes the price of goods,  is the quantity of the goods produced by firm i(i=1, 2), yi denotes the consumers’ expectation about firm i’s total sale. The parameter n and

is the quantity of the goods produced by firm i(i=1, 2), yi denotes the consumers’ expectation about firm i’s total sale. The parameter n and  measures the strength of network effects-lower value n indicates weaker network externalities. The firms produce the goods at a constant marginal cost c which is normalized to zero. Then the profits of firm i can be written as

measures the strength of network effects-lower value n indicates weaker network externalities. The firms produce the goods at a constant marginal cost c which is normalized to zero. Then the profits of firm i can be written as  | (4) |

3. Calculating Equilibrium Outcomes

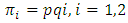

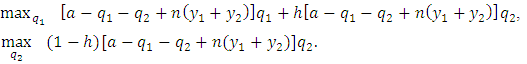

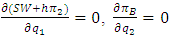

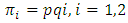

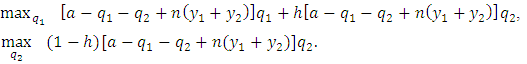

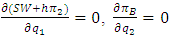

From (1), (3), (4) Shareholder A sets  to maximize

to maximize  and shareholder B sets

and shareholder B sets  to maximize

to maximize  as following, respectively:

as following, respectively: Then the best reaction functions are as following:

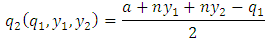

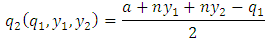

Then the best reaction functions are as following:  | (5) |

| (6) |

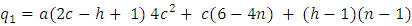

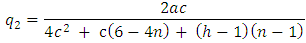

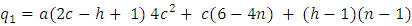

Then we consider the "rational expectations" conditions, which implies that in equilibrium  . Solving the reaction functions in (5) (6) together with

. Solving the reaction functions in (5) (6) together with  and

and  , we obtain the equilibrium outputs and profits as following:

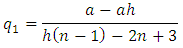

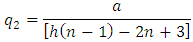

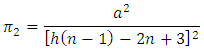

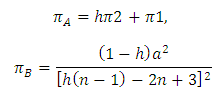

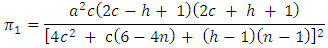

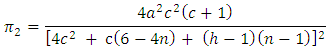

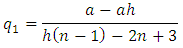

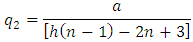

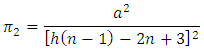

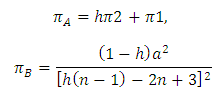

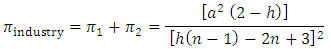

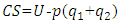

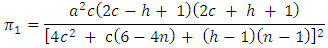

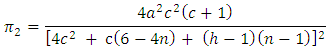

, we obtain the equilibrium outputs and profits as following:  | (7) |

| (8) |

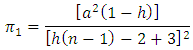

| (9) |

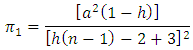

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

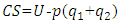

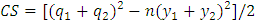

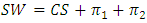

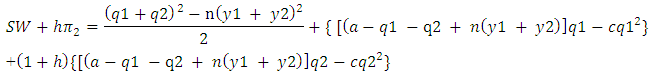

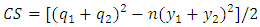

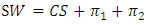

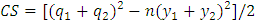

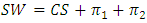

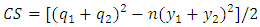

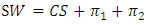

Following (2), consumer surplus  is given as

is given as  . Social welfare is given as

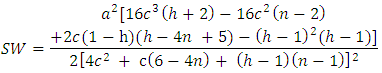

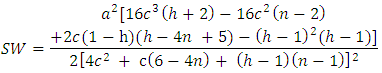

. Social welfare is given as  . When rational expectation realizes, by substituting of (7) and (8), we have:

. When rational expectation realizes, by substituting of (7) and (8), we have:  | (13) |

| (14) |

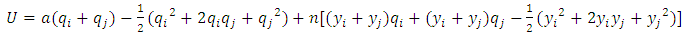

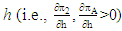

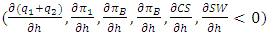

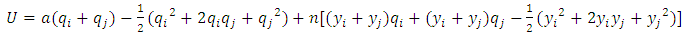

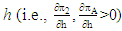

Lemma 1. The profits of firm 2, share holder A increase with  . However, industry output level, profits of firm 1, shareholder B, consumer surplus and social welfare are harmed by an increase of h

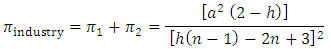

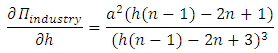

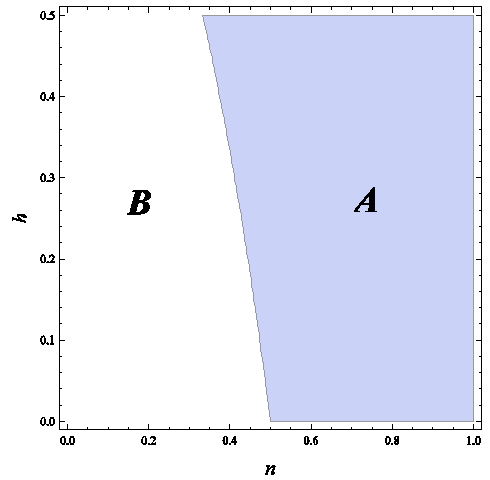

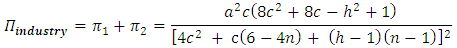

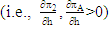

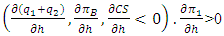

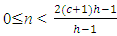

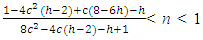

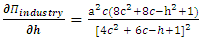

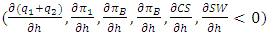

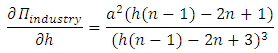

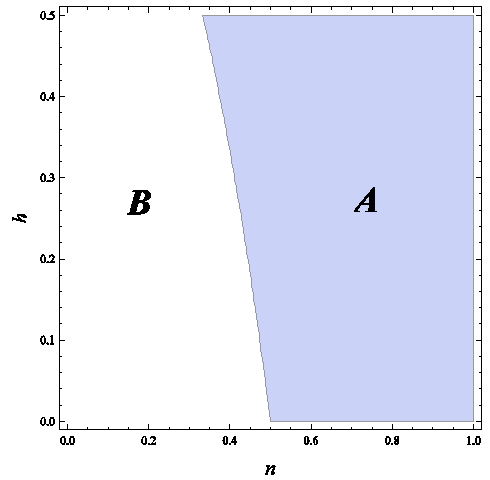

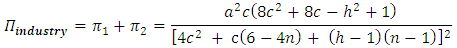

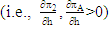

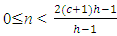

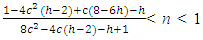

. However, industry output level, profits of firm 1, shareholder B, consumer surplus and social welfare are harmed by an increase of h  . Proposition 1. The industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease when the network effect is relatively strong. The conventional wisdom that the homogeneous products industry profits always increase with h for the anti-competitive nature of the cross-ownership reverses when we consider the network effect. Proof:

. Proposition 1. The industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease when the network effect is relatively strong. The conventional wisdom that the homogeneous products industry profits always increase with h for the anti-competitive nature of the cross-ownership reverses when we consider the network effect. Proof:  and

and  if and only if

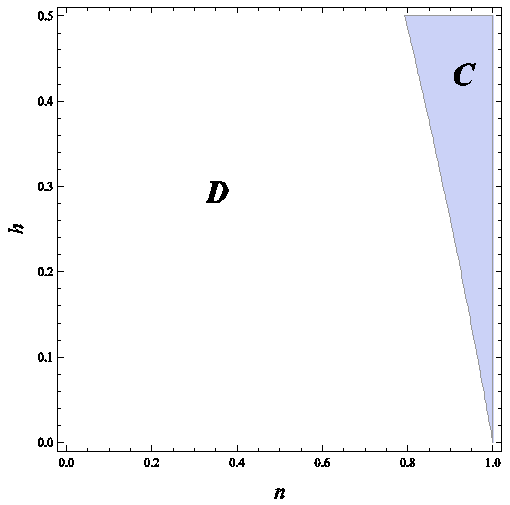

if and only if  Proposition 1 is shown in Figure 1 where

Proposition 1 is shown in Figure 1 where  applies in region A and

applies in region A and  applies in region B. The intuition behind this result is as follows. Lemma 1 shows that the industry output level decreases as h increases, and this implies that firms are more cooperative with h. This means that the positive effect on profits via consumers’ expectation becomes weaker as h increases. As the network effect becomes stronger, more aggressive play brings more profits to firms. When the network effect is sufficiently intense, the positive effect by the network effect becomes very weak in the cooperative play, even though the higher price can bring positive profit in the more cooperative play. Therefore, the industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease as h increases.

applies in region B. The intuition behind this result is as follows. Lemma 1 shows that the industry output level decreases as h increases, and this implies that firms are more cooperative with h. This means that the positive effect on profits via consumers’ expectation becomes weaker as h increases. As the network effect becomes stronger, more aggressive play brings more profits to firms. When the network effect is sufficiently intense, the positive effect by the network effect becomes very weak in the cooperative play, even though the higher price can bring positive profit in the more cooperative play. Therefore, the industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease as h increases.  | Figure 1.  in region A and in region A and  in region B in region B |

4. Extension

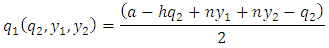

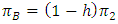

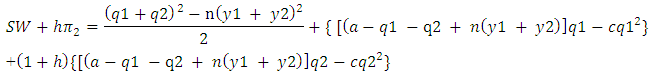

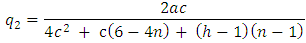

Here, we consider PCO activities in a mixed duopoly market with network effects. Consider a market consisting of a public firm 1 and a private firm 2 producing homogeneous network goods. There are two shareholders, A and B. Firm 1 is solely owned by shareholder A (state) while firm 2 is jointly owned by the two shareholders. Shareholder B has the majority of shares of firm 2 and thus controls firm 2. We denote by  the fraction of shares that shareholder A has in firm 2. The public firm 1 maximizes the social welfare

the fraction of shares that shareholder A has in firm 2. The public firm 1 maximizes the social welfare  . Therefore, shareholder A aims at maximizing the sum of the social welfare and the profits from firm 2

. Therefore, shareholder A aims at maximizing the sum of the social welfare and the profits from firm 2  . Shareholder B is assumed to maximize its total profit

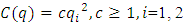

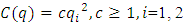

. Shareholder B is assumed to maximize its total profit  . The inverse demand function is as in eq.(3) in section 3. Following the tradition from mixed oligopoly literatures, we assume quadratic production cost

. The inverse demand function is as in eq.(3) in section 3. Following the tradition from mixed oligopoly literatures, we assume quadratic production cost  . Then shareholder A maximizes:

. Then shareholder A maximizes:  | (15) |

Shareholder B maximizes:  | (16) |

The firms set outputs in Cournot competition. The equilibrium must satisfy  . Together with the "rational expectations" conditions by imposing

. Together with the "rational expectations" conditions by imposing  and

and  , we obtain the equilibrium outputs and profits as following:

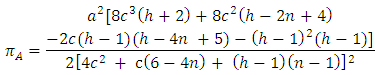

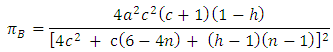

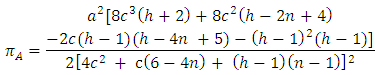

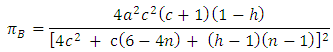

, we obtain the equilibrium outputs and profits as following:  | (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

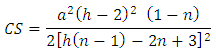

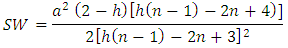

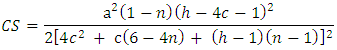

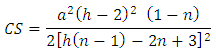

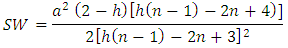

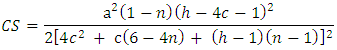

Consumer surplus is given as  . Social welfare is given as

. Social welfare is given as  . When rational expectation realizes, by substituting of (17) (18), we have:

. When rational expectation realizes, by substituting of (17) (18), we have:  | (24) |

| (25) |

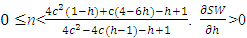

Lemma 2. The profits of firm 2, shareholder A increase with h  . However, industry output level, shareholder B and consumer surplus are harmed by an increase of h

. However, industry output level, shareholder B and consumer surplus are harmed by an increase of h  only if

only if  when

when  and

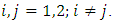

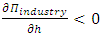

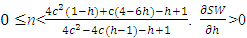

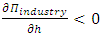

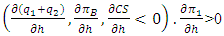

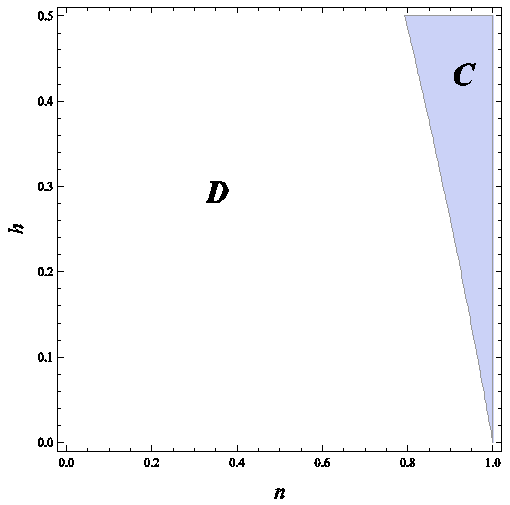

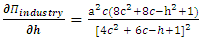

and  . Proposition 2. The industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease when the network effect is relatively intense.1 However, although consumer surplus decreases with h, social welfare may increase as h increases from Lemma 2. Proof:

. Proposition 2. The industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease when the network effect is relatively intense.1 However, although consumer surplus decreases with h, social welfare may increase as h increases from Lemma 2. Proof:  if and only if

if and only if  and this is shown in Figure 2 where

and this is shown in Figure 2 where  applies in region C and

applies in region C and  applies in region D.

applies in region D. | Figure 2. The figure is drawn for a given c=1.  in region C and in region C and  in region D in region D |

5. Conclusions

This paper investigates whether the conventional wisdom that PCO always increases the industry profits still holds in network industries. We find that the conventional wisdom reverses when the network effect is relatively intense. Our results are very meaningful for the firms in network industries to reconsider the problem of PCO. We considered the market is a homogenous good market, however, the products could be differentiated and the analysis of the problem of PCO under a differentiated duopoly market may be the future topic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are extremely grateful to anonymous referees and Prof. Mizuno Tomomichi, graduate school of Kobe university for their comments and suggestions that have substantially improved the quality of the paper.

Notes

1. The industry profit in the mixed duopoly under cross-ownership always increases with h without network effect. By substituting of n=0 into (23), we can get  and

and  always.

always.

References

| [1] | Barcena-Ruiz, J.C, Olaizola, N. (2007). Cost-saving production technologies and partial ownership. Economics Bulletin, 15, 1–8. |

| [2] | Fanti, L. (2013). Cross-ownership and unions in a Cournot duopoly: When profits reduce with horizontal product differentiation. Japan and the World Economy, 27, 34–40. |

| [3] | Fanti, L. and D. Buccella (2016). Network externalities and corporate social responsibility. Economics Bulletin, 36, 2043–2050. |

| [4] | Gilo, D. and Moshe, Y. and Spiefel, Y (2006). Partial cross ownership and tacit collusion. RAND Journal of Economics, 37, 81–99. |

| [5] | Gilo, D. and Spiefel, Y (2003). Partial cross ownership and tacit collusion. Working Paper The center for the Study of Industrial Organization at Northwestern University. |

| [6] | Katz, M. and C. Shapiro (1985). Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. American Economic Review, 34, 424-440. |

| [7] | Pal, R. (2014). Price and quantity competition in network gods duopoly: a reversal result. Economics Bulletin, 75, 1019-1027. |

| [8] | Pal, R. and M. Scrimitore (2016). Tacit collusion and market concentration under network effects. Economics Letters, 145, 266-269. |

the fraction of shares that shareholder A has in firm 2. The shareholders A and B are assumed to maximize their total profits

the fraction of shares that shareholder A has in firm 2. The shareholders A and B are assumed to maximize their total profits  and

and  , respectively as following:

, respectively as following:

Then, the inverse demand function can be derived as following:

Then, the inverse demand function can be derived as following:

is a parameter that captures the size of the market.

is a parameter that captures the size of the market.  denotes the price of goods,

denotes the price of goods,  is the quantity of the goods produced by firm i(i=1, 2), yi denotes the consumers’ expectation about firm i’s total sale. The parameter n and

is the quantity of the goods produced by firm i(i=1, 2), yi denotes the consumers’ expectation about firm i’s total sale. The parameter n and  measures the strength of network effects-lower value n indicates weaker network externalities. The firms produce the goods at a constant marginal cost c which is normalized to zero. Then the profits of firm i can be written as

measures the strength of network effects-lower value n indicates weaker network externalities. The firms produce the goods at a constant marginal cost c which is normalized to zero. Then the profits of firm i can be written as

to maximize

to maximize  and shareholder B sets

and shareholder B sets  to maximize

to maximize  as following, respectively:

as following, respectively: Then the best reaction functions are as following:

Then the best reaction functions are as following:

. Solving the reaction functions in (5) (6) together with

. Solving the reaction functions in (5) (6) together with  and

and  , we obtain the equilibrium outputs and profits as following:

, we obtain the equilibrium outputs and profits as following:

is given as

is given as  . Social welfare is given as

. Social welfare is given as  . When rational expectation realizes, by substituting of (7) and (8), we have:

. When rational expectation realizes, by substituting of (7) and (8), we have:

. However, industry output level, profits of firm 1, shareholder B, consumer surplus and social welfare are harmed by an increase of h

. However, industry output level, profits of firm 1, shareholder B, consumer surplus and social welfare are harmed by an increase of h  . Proposition 1. The industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease when the network effect is relatively strong. The conventional wisdom that the homogeneous products industry profits always increase with h for the anti-competitive nature of the cross-ownership reverses when we consider the network effect. Proof:

. Proposition 1. The industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease when the network effect is relatively strong. The conventional wisdom that the homogeneous products industry profits always increase with h for the anti-competitive nature of the cross-ownership reverses when we consider the network effect. Proof:  and

and  if and only if

if and only if  Proposition 1 is shown in Figure 1 where

Proposition 1 is shown in Figure 1 where  applies in region A and

applies in region A and  applies in region B. The intuition behind this result is as follows. Lemma 1 shows that the industry output level decreases as h increases, and this implies that firms are more cooperative with h. This means that the positive effect on profits via consumers’ expectation becomes weaker as h increases. As the network effect becomes stronger, more aggressive play brings more profits to firms. When the network effect is sufficiently intense, the positive effect by the network effect becomes very weak in the cooperative play, even though the higher price can bring positive profit in the more cooperative play. Therefore, the industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease as h increases.

applies in region B. The intuition behind this result is as follows. Lemma 1 shows that the industry output level decreases as h increases, and this implies that firms are more cooperative with h. This means that the positive effect on profits via consumers’ expectation becomes weaker as h increases. As the network effect becomes stronger, more aggressive play brings more profits to firms. When the network effect is sufficiently intense, the positive effect by the network effect becomes very weak in the cooperative play, even though the higher price can bring positive profit in the more cooperative play. Therefore, the industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease as h increases.

in region A and

in region A and  in region B

in region B the fraction of shares that shareholder A has in firm 2. The public firm 1 maximizes the social welfare

the fraction of shares that shareholder A has in firm 2. The public firm 1 maximizes the social welfare  . Therefore, shareholder A aims at maximizing the sum of the social welfare and the profits from firm 2

. Therefore, shareholder A aims at maximizing the sum of the social welfare and the profits from firm 2  . Shareholder B is assumed to maximize its total profit

. Shareholder B is assumed to maximize its total profit  . The inverse demand function is as in eq.(3) in section 3. Following the tradition from mixed oligopoly literatures, we assume quadratic production cost

. The inverse demand function is as in eq.(3) in section 3. Following the tradition from mixed oligopoly literatures, we assume quadratic production cost  . Then shareholder A maximizes:

. Then shareholder A maximizes:

. Together with the "rational expectations" conditions by imposing

. Together with the "rational expectations" conditions by imposing  and

and  , we obtain the equilibrium outputs and profits as following:

, we obtain the equilibrium outputs and profits as following:

. Social welfare is given as

. Social welfare is given as  . When rational expectation realizes, by substituting of (17) (18), we have:

. When rational expectation realizes, by substituting of (17) (18), we have:

. However, industry output level, shareholder B and consumer surplus are harmed by an increase of h

. However, industry output level, shareholder B and consumer surplus are harmed by an increase of h  only if

only if  when

when  and

and  . Proposition 2. The industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease when the network effect is relatively intense.1 However, although consumer surplus decreases with h, social welfare may increase as h increases from Lemma 2. Proof:

. Proposition 2. The industry profit under cross-ownership may decrease when the network effect is relatively intense.1 However, although consumer surplus decreases with h, social welfare may increase as h increases from Lemma 2. Proof:  if and only if

if and only if  and this is shown in Figure 2 where

and this is shown in Figure 2 where  applies in region C and

applies in region C and  applies in region D.

applies in region D.

in region C and

in region C and  in region D

in region D and

and  always.

always.  Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML