-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

p-ISSN: 2168-457X e-ISSN: 2168-4588

2017; 5(1): 6-21

doi:10.5923/j.m2economics.20170501.02

Do Depositors Discipline Banks in Nigeria?

Baba N. Yaaba1, Yakubu Shaba2, Abubakar Ibrahim3

1Statistics Department, Central Bank of Nigeria, Nigeria

2Department of Business Administration, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Nigeria

3Office of the Accountant General of the Federation, Federal Pay Office, Sokoto, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Baba N. Yaaba, Statistics Department, Central Bank of Nigeria, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Market discipline, particularly from depositor’s perspective, is believed to have the incentive for curbing excessive appetite for risk by banks, particularly if the information on discipline devices is to the knowledge of bank managers. Adopting a generalised method of moments closely related to that of Blundell and Bond (1998), the study investigates the concept of market discipline in Nigeria using quarterly micro-data from 2007Q1 to 2016Q4 across twenty four (24) banks. Typifying banks and deposits, the study finds evidence in support of market discipline for smaller and domestically-controlled banks, in terms of deposit reallocation, with foreign currency account holders as most active. The big and foreign-owned banks however pay higher deposit rate as compensation. In other words, there is the presence of the concept of too-big-to-fail and too-good-to-fail. The study advocates for increase in the dissemination of banks information to the Nigerian public, so as to enable depositors take proactive deposit decisions. It further recognises the need for Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) to toughen her supervisory role by adequately and openly sanctioning banks that violate regulatory provisions. This will not only serve as deterrent to others that might intend similar violations, but provide information about erring banks to depositors who will process and use them as discipline device.

Keywords: Regulators, Depositors, GMM, Discipline, Banking soundness

Cite this paper: Baba N. Yaaba, Yakubu Shaba, Abubakar Ibrahim, Do Depositors Discipline Banks in Nigeria?, Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2017, pp. 6-21. doi: 10.5923/j.m2economics.20170501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Although, the role of market in supervising banks had long been recognised by academic researchers1, it became appealing to the regulators with the introduction of Basel II Accord which is based on three complimentary pillars: capital requirements, supervisory review and market discipline. The Pillar III designed a set of disclosure requirements which is capable of availing market participants with vital information on the activities of banks to enable them take proactive banking decisions. The information disclosure covers the scope of application, capital status, risk appetite and risk assessment procedure.Some analysts fully support Pillar III disclosure requirements, contending that regular and timely disclosure of sufficient information could enhance transparency, minimise market disruptions2, lead to more efficient allocation of capital, strengthen shareholders control over management as well as appropriately reward well managed banks. Opponents were however sceptical about its efficacy asserting that excessive disclosure of bank information could lead to imprecision3, disrupt confidentiality, misalign incentive structures, induce panic reaction capable of exacerbating the already bad situation, ignite confidence tumbling which could lead to systemic crisis, among others. Thus, the concept was given less attention, particularly by the emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) until the global financial crisis (GFC) that emanated from the mortgage sector of the United States in 2007/08.Although banks demonstrated, to a large extent, compliance with Basel capital standards, but they still have their own share of the blame arising largely from their undue appetite for risks. Moreso, the GFC undoubtedly exposed colossal regulatory challenges, which include but not limited to the ‘hands-off’ approach to handling most of the pre-crisis symptoms. The aftermath of the GFC witnessed the birth of massively new rules to augment the existing set of bank regulations. For instance, at the international level, what can best be referred to as Basel 2.5 and Basel 3 had long evolved4. In Nigeria, various measures were taken including strict enforcement of corporate governance codes, risk-focused and rule-based regulatory framework, zero tolerance regulatory frameworks in data rendition, among others5. Analysts are however, beginning to question the efficacy of these rules to forestall the possibility of another crisis (Fullenkamp & Quintyn, 2014). They are of the opinion that although the development of new rules is always the immediate preference of the political class when crisis erupts without due consideration for the optimal deployment of the existing alternatives. More rules on banks and bankers, according to them, are likely to be less effective than the strategy of imposing additional responsibility on the bank supervisors and market participants.In this paper, we believe in both approaches hence attach importance to the placement of additional responsibilities at the doorstep of not only the supervisors but also market participants considering the possibility of cases of moral hazards. Thus, the paper is an attempt to examine the effort of the market participants, particularly depositors in penalising banks in Nigeria for their recklessness and compensating others that are well managed within the ambit of the law. As a departure from earlier studies on this topic, however, the paper seeks to ascertain the disciplinary tendency of different depositors’ type, considering the possibility of variations in their level of financial literacy. The paper is structured into five sections. Following this introduction is section two which explains the concepts and models of market discipline as well as earlier empirical literature on same or similar subject. Section three describes the methodology and data sources, while section four analyses the empirical results and the last section concludes.

2. Theoretical Underpinning and Empirical Literature

- Market discipline in the banking sector arises when private sector players such as shareholders, depositors and creditors attempt to “run-to-quality” arising from increasing appetite for risk by same banks. In other words, market discipline is a mechanism through which market forces punish banks that are poorly managed, while rewarding those that are effectively managed, thereby entrenching prudence and efficiency. Market discipline can either be direct or indirect. Both insured and uninsured depositors, for instance, who realizes, from the information available to them, that a bank has developed excessive appetite for risk or violate regulatory requirements, may decide to penalize the bank either by withdrawing their deposits (run-to-quality) or bargain for higher deposit rate (Martinez Peria & Schmukler, 2001). Thus, banks who have depositors that are highly sensitive to their risk are likely to be more cautious in developing excessive appetite for risk, knowing fully well that they would have to contend either with trivial deposit base or payment of soaring deposit rate, if they take excessive risk (Hosno, Iwaki & Tsuru, 2004).

2.1. Theoretical Underpinning

- Depositors DisciplineSome economists have argued that Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is the underlying foundation for market discipline in banking. They contend that depositors as well as other stakeholders in the banking sector, if well equipped with relevant information, have the capability to restrict banks’ appetite for risk through market mechanisms. Efficient Market Hypothesis assumes that the market is likely to be at an efficient level, if there are no transaction costs and information asymmetries, and that any intervention by government might only serve as an additional incentive to bolster market’s appetite for risk taking thereby disrupting equilibrium. Proponents of market discipline, therefore, advocate increasing efforts toward measures that are capable of enhancing market discipline; contending that it would improve the stability and soundness of the financial system not only via direct discipline but also as a means of providing critical market signals, on not only risk but also other management malpractices to the regulators to take proactive policy measures.Government RegulationThe theoretical welfare economics spearheaded by A. C. Pigou in 1932 saw the birth of Public Interest Theory6 which serves as one of the justification for bank regulation7. Public Interest Theory holds two prominent assumptions: First, the bank regulators are presumed to have sufficient information as well as adequate powers to protect and promote public interest; and second, the regulators are highly passionate about their role such that the objective of safeguarding public interest is always almost at peak. The sole objective of regulation, according to the Public Interest Theory is to remedy market malpractices arising from market inefficiencies. Three types of market failures are broadly identified, namely: market misconduct, information asymmetry and externalities. Following Jensen (2012) however, there are some politically motivated objectives of financial regulation viz; to ensure stability and soundness of the financial system so as to safeguard the confidence of the public. At the heart of this paper is the concept of information asymmetry.Information Asymmetry as one of the reasons behind market failure is considered as a situation where one contracting party is relatively at advantage in terms of either access to information or better information, thereby leading to market failure arising either from adverse selection, moral hazard and information monopoly. The context is highly relevant for principal-agent problem, which arises when a party (say the agent) has the responsibility of taking decision on behalf of the other (say the principal) without the principal been able to sufficiently supervise the agent. Thus, the agent in some instances act in his own best interest rather than in the interest of the principal. The case becomes worse when the agent gets an implicit guarantee of support of any means in terms of losses arising from his actions – Moral Hazard. The guarantee in the case of banking could be in form of insurance pay-outs or bail-out.When commercial banks, for instance, become sure of government intention to absorb losses that are the responsibilities of bank creditors, there is the tendency for the bank managers to take more than optimal risks so as to gain more profits while throwing the cost of failure at the doorstep of government. This also applies when there is implicit deposit insurance. These actions of the agent generate, in most cases, negative externalities for the third party.The scenarios of liquidity mismatch8 also ensue in some cases. In this case, since large portion of deposits are of short-term arising from the nature of deposits and depositors. An attempt to invest the deposit in long-term projects usually result in liquidity crisis arising either from high rate of default9 or long-term maturity of investment. There could also be cases of macroeconomic problems that could lead to liquidity squeeze. Consider, for instance, the case of low level of economic activities arising naturally from business cycle, inflation or tightened credit conditions by central bank that leads to low aggregate demand. These reasons, among many others, provide clues on the possibility of banks engaging in activities that are inimical to the interest of stakeholders, as well as stability and soundness of the system, thus justify the effort of the regulators to device various means of dealing with the problems10. Unfortunately, however, bank managers are powerful enough to exert political influence on the regulators to avert the use of the instruments and the sanctions that could result therefrom. Hence the need for the depositors themselves to monitor banks so as to take proactive measures either by demanding more interest for higher risk or by running to quality.The focus of this paper is on those actions that were taken by banks that could lead to liquidity problem and by no means capable of, in ordinary circumstances, causes insolvency and systemic risk.

2.2. Review of Empirical Literature

- Adolfo and Roberto (2000) employed pooled, fixed and random effects techniques to assess the concept of depositors discipline for Colombian banks using semi-annual panel data from 1985 to 1999. The study found a direct relationship between deposit growth and bank fundamentals, even after controlling for other risk-return factors. They noted that banks strive to improve on their operations during deposit losses, and that banks with strong fundamentals enjoy lower deposit rate and higher lending rates. They, therefore conclude that the concept of depositors discipline, perhaps complemented by regulatory efficiency exist for Colombia during the study period. They also reported a limited case of moral hazard precipitated by deposit insurance. Birchler and Andrea (2001) utilized an unbalanced panel data of two hundred and fifty (250) banks in Switzerland over the period 1987 to 1998. The results reveal a substantial evidence of market discipline as the depositors of Swiss banks demonstrate a considerable sensitivity to banks fundamentals, institutional differences across bank group as well as changes in depositor’s protection policies. Martinez Peria and Schmukler (2001) empirically evaluated the interactions between market discipline and deposit insurance, as well as the consequences of banking system crises on market discipline in Argentina, Chile and Mexico during the 1980s and 1990s. The study which used bank-level data adopted generalized method of moments (GMM) technique and found evidence of depositors’ discipline both from the perspective of deposit withdrawals and bargaining for higher deposit interest rates even in the face deposit insurance. This is evidenced in the pre-crisis period and sporadically increased during and after the crises.Mark (2001) theoretically proved that considering subordinated debt and common equity as proxies for market discipline, subordinated debt is relatively more efficient than equity not only in terms of a source of market discipline but also as a form of bank capital.Hosono, Iwaki and Tsuru (2004) investigated the potency of depositor discipline and its link to bank regulation and supervision using annual panel data of seventeen thousand banks, across sixty countries, covering the period 1992 through 2002. They found evidence in support of reduction in deposit interest rate and its sensitivity to bank risk taking behaviour arising from strict regulations on bank activities and powerful supervisory activities. They submitted that stringent regulation and supervision of banks arising from colossal bailout of insolvent banks lead to banking system fragility and weak market discipline.Goday, Gruss and Ponce (2005) tested the validity of depositors discipline in Uruguay using panel data. The study divided the data into three different periods. First, the pre-crisis period starting from January 2000 to December 2001, while the second period covers the crisis period in Uruguay from January 2002 to July 2002 and the third category was from August 2002 to December 2004, a period after the crisis. The study found strong evidence in support of the depositors discipline hypothesis through deposit withdrawal from riskier banks. The hypothesis that depositors require higher interest rates was however weak for the country during the studied period. The study further revealed that banks also in-turn react to depositors’ actions particularly in the post crisis period.Adam (2006) examined the concept of market discipline for a sample of 1,200 commercial banks from 1976 to 2004 and 2,500 bank holding companies from 1986 to 2004 in the US. The study which adopted both Probit and OLS techniques reported that market plays a crucial role in regulating the selected banks and bank holding companies during the study period. Berger and Turk-Ariss (2010) examined the response of both deposit growth and deposit risk premiums on bank risk taking behaviour for over 2000 commercial banks and bank holding companies across the US and 22 EU countries from 1997 to 2007. They run various tests along the lines of the US and EU; and institutions above and below US$50.0 billion in total assets, so as to determine if differences exist due to variations in the level of insurance coverage, capacity for bailout interventions in terms of banking crisis and the speculation about the concept of too-big-to-fail in the US and EU, among other differences. They found that, although the level of discipline varies across countries, sizes of the banks and listing in the stock market, but depositors indeed disciplined banks in both the US and EU. Depositors, according to the authors, react more to equity ratios than the quality of loan portfolio. A case they considered consistent with Basel III requirement of increase in the minimum Tier 1 common equity.Cubillas, Fonseca and Gonzalez (2010) analysed the effect of banking crises on market discipline using a panel data of banks from sixty six (66) countries covering seventy nine (79) banking crises. The study employed GMM first difference estimator for the analysis covering the period 1989 to 2007. The result reveal that market discipline weakened post crisis especially in countries where regulation, supervision, and regulatory institutions strongly advocate the concept prior to the crisis, as well as embark on aggressive measures to curtail the consequences of the crisis in case they occur.Romera and Benjamin (2010) investigated the efficacy of depositors discipline for Brazil between 1994 and 2004 using GLS technique. The results show that depositors, during the study period, clearly demonstrated their commitment to well managed banks, both from the perspective of deposit volume and cost, but with more emphasis on deposit volume. Their results further show that depositors also respond to macroeconomic environment with less regard to government regulatory effort. Finally, the concept of too-big-to-fail seems to play a role in the Brazilian banking system.Hamada (2011) utilized semi-annual panel data of sixty eight (68) commercial banks in Indonesia from 1998 to 2009 to examine the concept of market discipline by depositors. The study which adopted both changes in the amount of deposits and deposit interest rate as measures of depositor discipline found among others that soundness/fragility of banks and equity ratio are of interest to Indonesian depositors. Alexei, William and Koen (2010) studied the concept of market discipline in Russian deposit market after the 1998 crisis. The study adopted GMM estimator on dynamic panel data covering the period 1997 through 2002. They found strong evidence in favour of the validity of the concept via both deposit quantity and price. The results show that market discipline in Russia became stronger with the 1998 financial crisis and largely led by the enterprise depositors rather than households. Relatively more pressure during the study period was on smaller banks, undercapilised banks as well as unhealthy banks.Raquel, Rafael and Lucas (2011) examined the concept of run-to-quality by depositors from smaller banks to bigger banks in Brazil after the GFC using pooled ordinary least squares (POLS) and the system of GMM. The semi-annual data used spanned the period 2001 to 2009. The results reveal that deposit holders ran from smaller banks to big banks believing that bigger banks were too big to fail and that the movements were largely spearheaded by institutional depositors such that small banks with larger institutional deposit base suffer remarkable deposit outflow especially during the crisis.Ezema (2013) adopted a two-stage framework as well as a two-channel approach to investigate the concept of depositors’ discipline of Deposit Money Banks (DMBs) in Nigeria using panel data. The results support the concept with more clarity on the quantity channel implying that depositors reduce their deposit portfolio in poorly managed banks. The findings did not however show that banks respond to signals from depositors except those from other banks.Hassan, Jackowicz, Kowalski and Kozlowski (2013) used deposit volume as a proxy for market discipline to test the existence of the concept of depositors discipline for the CE countries including but not limited to Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Korea, Netherlands, Russia, Sweden and USA. The authors employed dynamic panel model in the form of system-GMM and used data spanning the period 2007 through 2010. The study finds that the global financial crisis of 2008 did not enhance the sensitivity of depositors to accounting risk measures and that the depositors’ responses were a consequence of negative rumours from the press. They concluded that the reaction of depositors to information outside banks have severe consequences since depositors discipline is considered a viable alternative for market regulation of banks.Moch-Doddy (2013) assessed both the disciplining signal hypothesis (DSH) and corrective response hypothesis (CRH) for Indonesia using a combination of market and accounting data from 2000 to 2010. The study which used thirteen different variables, applied a two stage empirical design on a panel data of one hundred and ten (110) banks. It utilised pooled, fixed and random effects estimation techniques. The results support the concept of disciplining signal hypothesis for Indonesia. The implication is that, market discipline mechanism is below optimal for Indonesia. The authors suggest improvement in the regulation of banks by the regulatory authorities so as to promote banking system soundness in the country.Hamid (2013) used a dynamic GMM panel analysis for the lagged dependency of changes in deposit volume to determine the concept of depositors discipline for East Asian banks between 1995 and 2005. The findings do not support the notion that depositors tend to demand higher deposits from weak banks. The author attributed the results largely to massive outflow of funds during the GFC as well as the regulations on interest rate.Berger and Turk-Ariss (2014) examined the possibility of government intervention in the GFC to diminish the concept of market discipline in the US and EU. The study utilised data from 1997 to 2007 for pre-crisis period and from 2008 to 2009 for crisis period. The study which utilised random effect technique, found that depositors discipline existed in both the US and EU prior to the crisis but reduced remarkably during the crisis except for small banks in the US.Hamid (2015) analysed the concept of market discipline for the East Asian banking sector in the context of information disclosure using a dynamic panel data analysis in the form of differenced-GMM. The countries covered include; Indonesia, Korea, Philippines and Thailand. The study which adopted deposit growth rate as proxy for market discipline include as predictor, bank and country specific variables such as interest rate, disclosure index, total equity to total assets, return on equity, liquid assets to total assets, among others. The study covered the period 1995 to 2005. The results confirm that depositors discipline enhances healthy and sound banks to disclose more information as it attracts more deposits. They submitted that the finding supports the Pillar III proposition of the Basel II Accord.Piotr, Danny, Enrico and Klaus (2015) examined the monitoring effort of bank debt holders in the US using difference-in-difference GMM estimation technique. The sample which was from 1983Q1 to 1993Q2 cut across five thousand five hundred and six (5,506) banks in all the fifty (50) states in the United States11. The results reveal that with strict monitoring by depositors, deposit rates are likely to decline as interest rate increases for non-deposit liabilities thereby incentivising junior debt holders for further monitoring of banks. Monitoring, on the other hand, in-turn influences the behaviour of banks. Lamer (2015) investigated depositors’ sensitivity to bank failures during the GFC within a regional context. The study utilised a panel data of 6,735 banks in 2,328 different markets (388 from MSAs and 1,940 from non-MSA countries) for a period of seven (7) years, from 2007 to 2013. Adopting ordinary least squares (OLS) as an estimation technique, the findings show enhanced depositors discipline in the local banking market even in the face of deposit insurance schemes and colossal bailouts. The sensitivity of depositors to bank fundamentals was far more pronounced in markets that have witnessed banks failures.Calomris and Jaremski (2016) investigated deposit competition and risk taking behaviour of banks in some states in the US before and after the introduction of deposit insurance. While the first set of data employed was annualised from the period 1900 to 1920, the second set was biennial for the same period. The data covered a total of nine thousand and sixty seven (9,067) state banks and one thousand nine hundred and twenty two (1,922) national banks. The findings reveal that deposit insurance precipitated higher risk as it discouraged market discipline which hitherto served as a check on uninsured banks. They contended that insolvency risk of insured banks are enhanced, hence they competed keenly for deposit of uninsured neighbouring banks.

3. Empirical Methodology, Data Issues and Implementation Strategy

3.1. Empirical Methodology

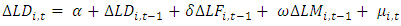

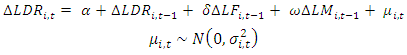

- The study basically concentrates on testing the direct effect of market discipline with the assumption that deposit insurance in Nigeria is not strong enough to induce moral hazard. This implies a situation when depositors react to the risk appetite level of banks in Nigeria by affecting quantity and/or cost of deposits. The empirical implementation therefore takes two different but interrelated dimensions12, implying that two set of models were estimated to examine the concept of market discipline in Nigeria. While the first model considers the quantity effect (run-to-quality), the second model is concerned with the price effect (cost of deposit). In each model, the reactions of deposits to bank risk taking proxies, regulatory requirement and macro-fundamentals were tested.To allow for unobserved bank heterogeneity and impending endogeneity, the study employs Generalized Method of Moments (GMM-Difference) estimator for dynamic panel data similar to that of Blundell and Bond (1998) and as adopted by Oliveira, Schiozer and Barros. (2011)13. This is to avoid the problem of dynamic panel bias arising from estimating these types of equations with lagged dependency using static panel or OLS technique. GMM has the capability to handle autoregressive in the dependent variables (deposit and deposit rate).Thus, the general reduced forms of the estimated equations are:Run-to-Quality Model:

| (1) |

| (2) |

3.2. Data Issues and Implementation Strategy

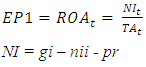

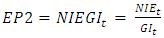

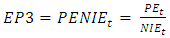

- The Deposit (D) as used in equation (1) attracts different meanings since each equation is run a number of times using different variants of D. The first approach at running equation (1) considers D from the perspective of the total outstanding deposit of all the DMBs. Thereafter, a dichotomy was established between demand deposit and other deposits. The third stage considers savings deposit. The fourth uses term/time deposits and the last looks at foreign currency deposits. This segregation is informed by the fact that the financial literacy of different category of depositors is likely to vary. Another twist at running both equations is the segregation of banks into foreign-controlled and locally owned banks; five biggest banks and other banks from the perspectives of assets. DR as presented in the equation is the deposit rate derived by imposing interest expense on outstanding deposits. The variable F is a vector of bank fundamentals and regulatory variables which include those variables that reflect the financial soundness indicators in line with the IMF financial assessment program initiated in the 1990s, namely: capital adequacy; asset quality; earnings and profitability; and liquidity. Management quality as contained in CAMELS analysis is assumed to be reflected in asset quality and earnings and profitability. The derivations of the variables are explained in-turn as follows:Capital Adequacy Indicators (CA): There are three core indicators of capital adequacy, following the IMF-FSI guideline15. The indicators are: regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets, Regulatory Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted assets and nonperforming loans net of provision to capital. Regulatory capital is as defined by the Basel Committee on banking supervision and comprises three tiers of capital (i.e. Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3). This study however adopted regulatory capital (RC) to risk weighted assets (RWA) as a proxy for capital adequacy.

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

4. Discussion of Estimated Results

4.1. Statistical Properties of the Data

- A multivariate analysis of this nature requires exploration of the variables used for the estimation. There is also the strong need to examine the distribution of the response and explanatory variables as well as a summary statistics of the data so as to have an insight into the characteristics of the series.

4.2. Summary Statistics of the Variables

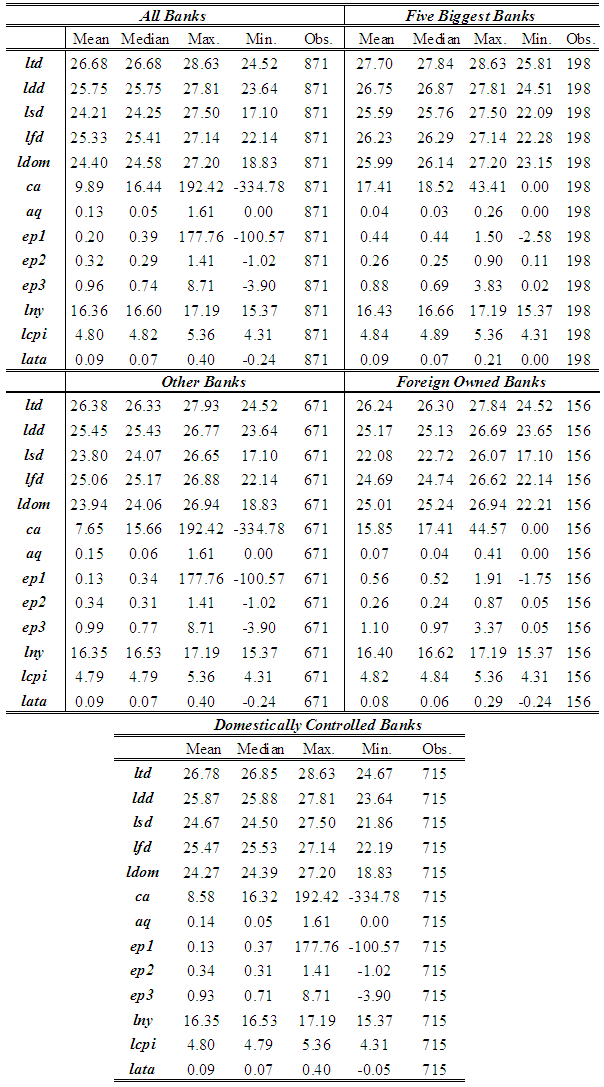

- Descriptive statistics of the variables used for the estimation were carried out from five different perspectives in line with the regression. The first considers the entire sample (i.e. all the twenty four (24) banks). The second covers the five biggest banks in terms of assets. The third includes banks other than the five biggest. The fourth and fifth grouped the banks in terms of ownership – foreign owned banks and domestically controlled banks, respectively. Most of the statistics return similar results. For instance, the mean and median of the entire sample stand at 26.68 each, while the five biggest banks recorded 27.70 and 27.84 respectively. Other banks yield a mean and median of 26.38 and 26.33 respectively. In the same vein, foreign owned and domestically controlled banks had an average and median scores of 26.24 and 26.30; and 26.78 and 26.85, respectively.The maximum and minimum distribution for all banks stand at 28.63 and 24.52, respectively while for the five biggest banks, other banks, foreign owned banks and domestically controlled banks stand at 28.63 and 25.81; 27.93 and 24.52; 27.84 and 24.52 and 28.63 and 24.67, respectively (Table 1).

| Table 1. Summary Statistics |

4.3. Correlation Matrix

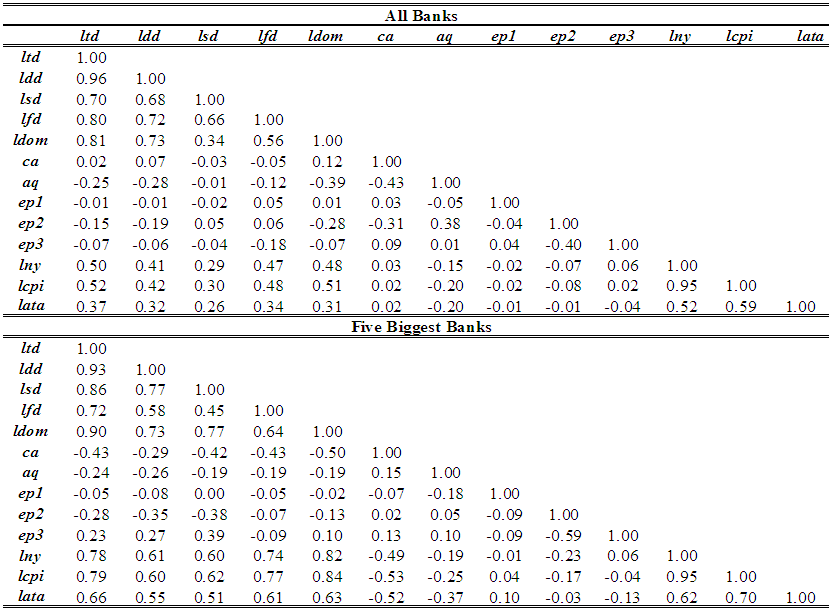

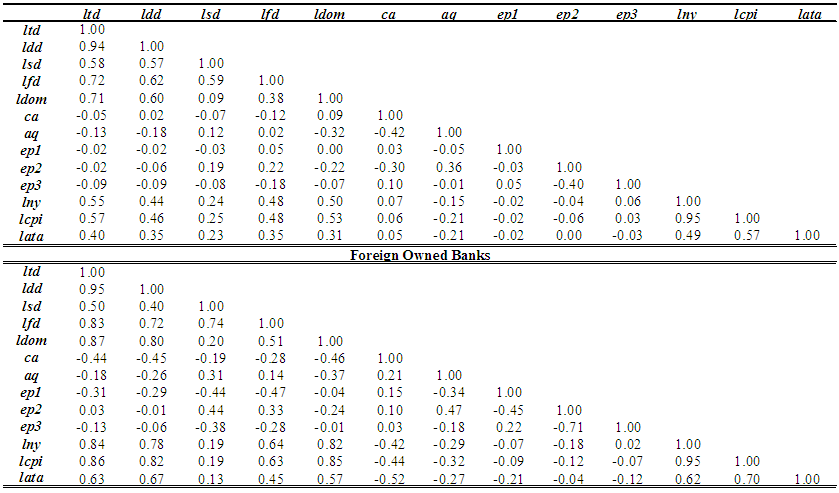

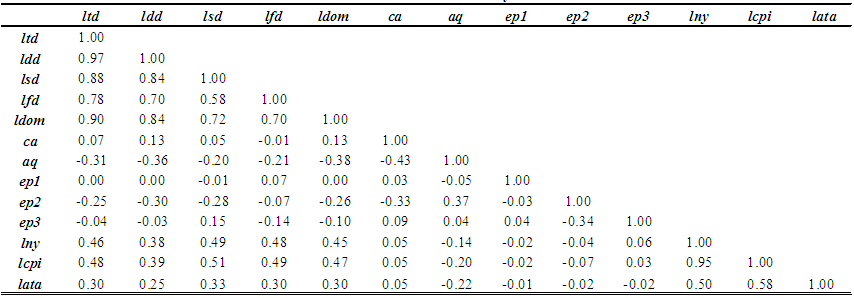

- Correlation matrixes are reported as Tables 6 to 10. From the tables, it is evident that ltd, ldd, lsd, lfd and ldom are highly correlated. This ordinarily would have signal the possibility of serial correlation but fortunately the variables represent the vector of dependent variables used one after the other. In other words, there are no two combinations of any of the variables that were included in the same regression.The correlation matrix for all banks as reported in Table 6 reveals the highest positive correlation of 0.95 between lny and lcpi, followed by 0.59 for lcpi and lata. Table 7 also shows that lny and lcpi which are control variables return a high positive coefficient of 0.95, followed by 0.84 between ldom and lcpi. Similar trend is reported for other banks as presented in Table 8. High positive correlation is established between lny and lcpi (0.95) and between lcpi and lata (0.57). In the case of foreign owned banks, lny and lcpi recorded the highest correlation of 0.95, followed by ltd and lata (0.86) and ldom and lcpi (0.85). lny and lcpi maintain their position in domestically controlled banks as in all others, while lcpi and lata yields 0.58 to come second.Overall, the high correlation among some variables presupposes the existence of serial correlation but the variables are not all included in the regression at the same time. Moreso, the Durbin Watson statistics reported by all the regressions provide evidence against the presence of serial correlation.

| Table 2a. Correlation Matrix – All Banks |

| Table 2b. Correlation Matrix – Other Banks |

| Table 2c. Correlation Matrix – Domestically Controlled Banks |

4.4. Estimated Results

- Apart from isolating the banks in terms of size and ownership structure, different deposit types are also considered separately, with the assumption that some class of depositors are likely to be more financially literate than others, hence variations in the level of discipline that could possibly be exerted on them. For instance, in addition to total deposit, the study also considered saving deposit, demand deposit, term/time deposit and foreign currency deposit as dependent variables one after the other.

4.4.1. Run-to-Quality Effect

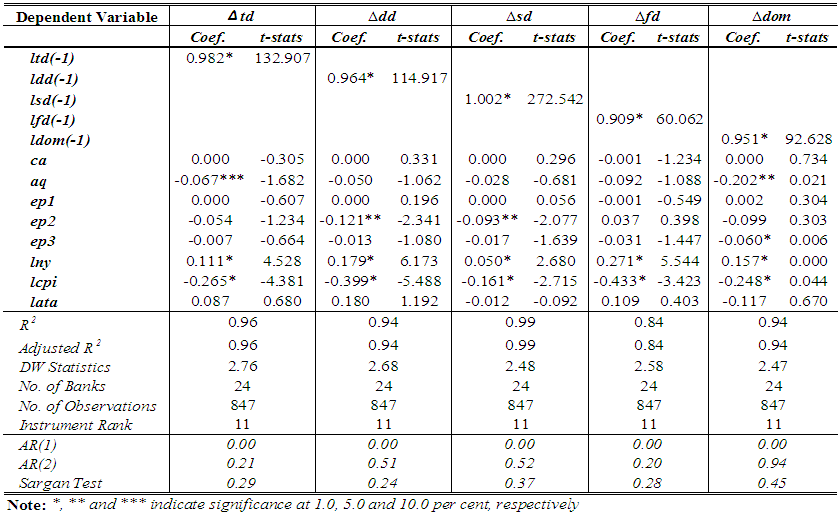

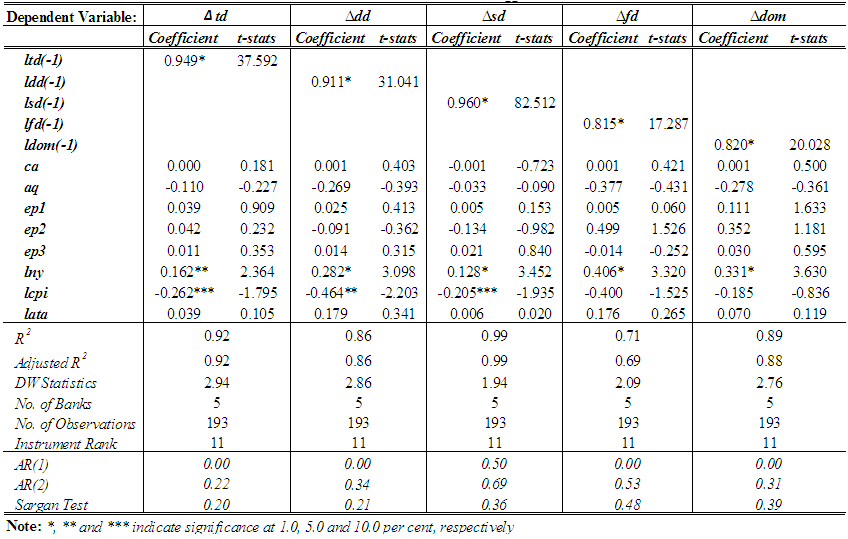

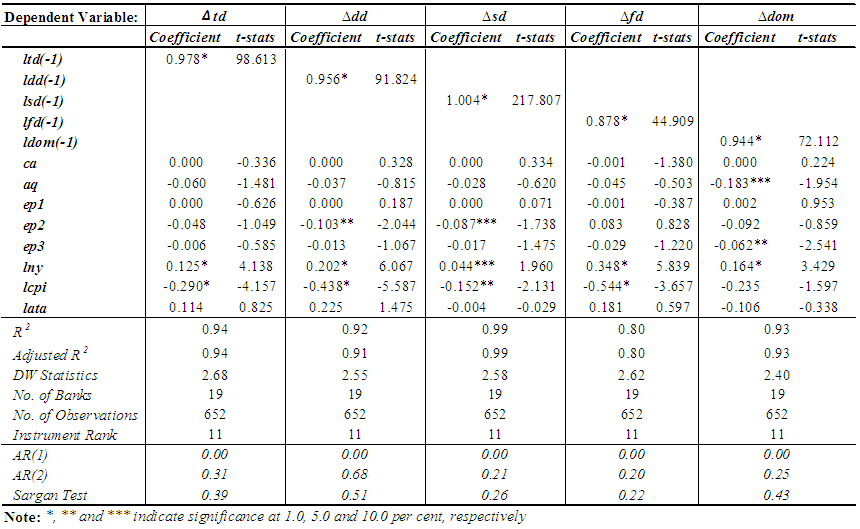

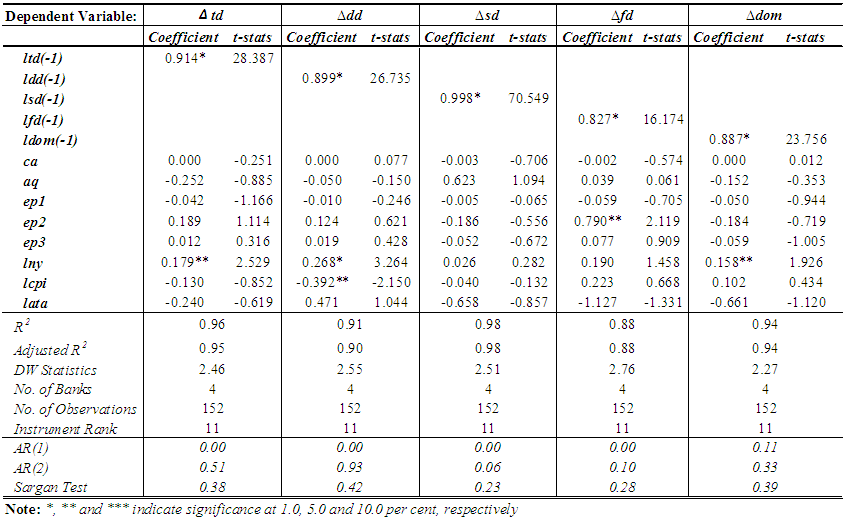

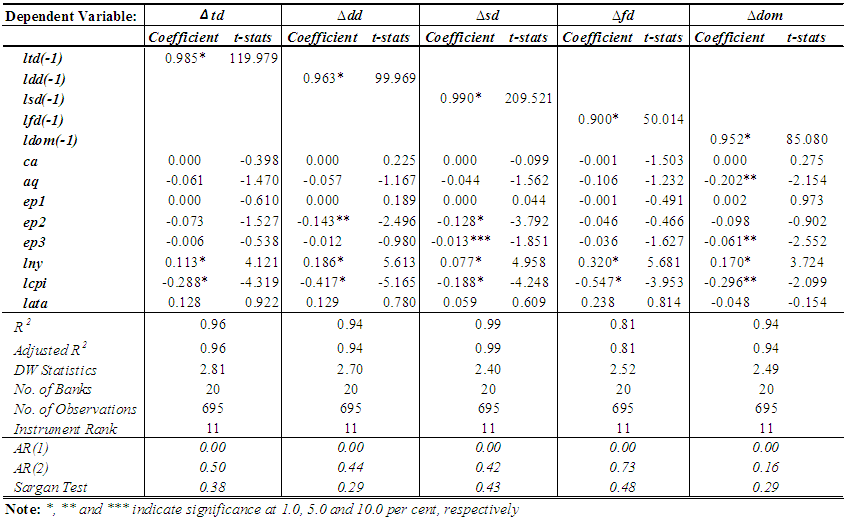

- To start with, Table 3 presents the results of all the sampled banks across all deposit types. In the case of total deposit, aq yields a significant negative coefficient, while ep2 in both cases of demand and saving deposits recorded negative and highly significant coefficients. Domiciliary account holders respond negatively to aq and ep3. However, all deposit types respond significantly to both macroeconomic variables (i.e. level of economic activities and inflation).

| Table 3. Estimation Results – All Banks |

| Table 4. Estimation Results – Five Biggest Banks |

| Table 5. Estimation Results – Other Banks |

| Table 6. Estimation Results – Foreign-Controlled Banks |

| Table 7. Estimation Results – Domestically-Controlled Banks |

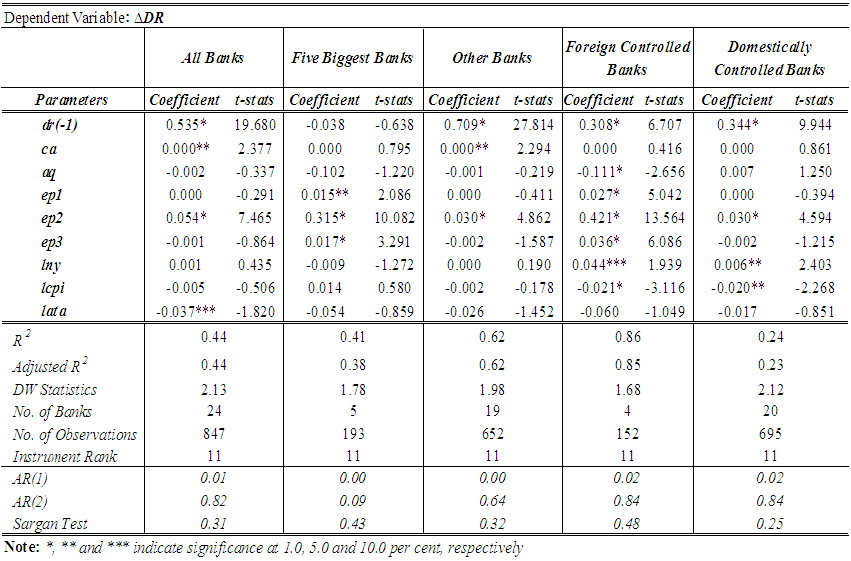

4.4.2. Pricing Effect

- The results of the pricing effect are presented as Table 8. A cursory examination of the table reveals that, the first, second and third columns present the results for all banks, five biggest banks and other banks, respectively. While columns five and six show results of foreign-owned and domestically-controlled banks, respectively.

| Table 8. Estimation Results – Deposit Rate |

4.5. Summary of Findings

- Overall, the results show that while depositors consider macroeconomic variables in their deposit decisions, ability to satisfy regulatory requirements is a non-issue to depositors particularly for big (too-big-to-fail) and foreign-controlled banks (too-good-to-fail). Banks other than the five biggest banks are however penalised by the quest for higher deposit rate to be able to retain their depositors. Banks specific characteristics in terms of: asset quality, earnings and profitability/management quality, matter most for banks other than the five biggest, as well as domestically controlled banks. In other words, beyond the confirmation of too-big-to-fail, there is also what can best be referred to as too-good-to-fail in Nigeria. Nigerian depositors do not only consider some banks in Nigeria as too-big-to-fail but they also perceive foreign owned banks as too-good-to-fail. Hence, they neither punish them for their excessive appetite for risk nor their penchant to flout regulatory requirements through deposit relocation. These notions of ‘too-big-to-fail’ and ‘too-good-to-fail’ can also be attributed to ability of big banks and foreign owned banks to pay relatively higher deposit rate as evidenced in Table 8. Thus, depositors generally prefer to respond to excessive appetite for risk or poor management by big and foreign-owned banks through demand for higher deposit rate against shifting their deposit base. Moreso, it is important to note that foreign currency depositors react more, in terms of deposit relocation, to bank fundamental than any other depositor type, followed by savings depositors, then demand depositors. Term/time depositors seem to bother less about the happenings in the market.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

- Market discipline, particularly from depositor’s perspective, is believed to have the incentive of curtailing banks excessive appetite for risk and improve their managerial prowess, particularly if the possibility of occurrence of these measures is to the knowledge of bank managers. Adopting a generalised method of moments closely related to that of Blundell and Bond (1998), this study examines the concept of market discipline in Nigeria using quarterly micro data from 2007Q1 to 2016Q4 across twenty four (24) banks. Different variants of the formulated equations (i.e. equations 1 and 2) were estimated. First, the estimation of equation (1) considers all banks, then five biggest banks, banks other than five biggest, foreign-controlled banks and domestically-controlled banks. In each case, five objective functions were considered namely: total deposits (td), demand deposits (dd), saving deposits (sd), term/time deposits (fd) and foreign currency deposits (dom). This gives us a total of twenty five regressions. Thereafter, considering deposit rate as the objective function across five categorizations of banks, another set of five regressions were carried-out, yielding a total of thirty (30) different regressions.The results reveal existence of market discipline (in terms of deposit relocation otherwise referred to as run-to-quality) in Nigeria, with emphasis on smaller banks (banks other than the five biggest in terms of assets) and domestically-controlled banks (banks wholly owned by Nigerians). In other words, there is the presence of the concept of too-big-to-fail and too-good-to-fail in Nigeria. While the five biggest banks are considered too-big-to-fail, the foreign owned banks are treated as too-good-to-fail; hence they are largely exonerated by the market as far as the concept of run-to-quality is concerned. The depositors instead resort to pricing effect to discipline the two set of banks. This happens even if the banks (five biggest and foreign owned banks) flout regulatory requirements. The study also finds foreign currency account holders to be most active in disciplining banks, in terms of deposit realignment, followed by savings account holders and then demand deposit holders. Macroeconomic variables do not however segregate the market as evidence shows that they take their toll on all banks. While robust economic activities enhance the level of deposit, inflation serves as a disincentive to save.With this development, therefore, the study advocates for increase in the dissemination of banks’ information to the Nigerian public, so as to enable depositors take proactive deposit decisions. The CBN should consider publishing monthly accounting data of individual banks on her website as well as urge banks to make same available on their own websites. This, if done, is likely to strengthen market discipline which is capable of complementing the supervisory efforts of the CBN. There is also the need for CBN to toughen her supervisory stance, not necessarily in terms of designing additional regulatory requirements, but appropriately and openly sanctioning banks that violate her regulatory provisions. This will not only serve as deterrent to others that might intend similar violations but also provide information about erring banks to depositors that will enable them take further actions to reward well-behaved banks and discipline poorly managed ones. A situation whereby erring banks are either not sanctioned or quietly sanctioned does not promote market disciplining devices particularly of the depositors.

Notes

- 1. See Litan 1987; Pierce, 1991.2. As lack of information leads to uncertainty.3. For instance, impairment in loan portfolio. See Simon Topping4. We also have the revisions of Dodd-Frank Act in the US, Vickers report in the UK and the Liikanen report in the EU.5. See Sanusi (2012).6. There is also the private interest theories of regulation, see Johan, (2010) for details.7. See Jensen, 2012.8. Short-term funding for long-term investment.9. Inability of the creditor to pay back as well as the difficulty of getting another investor to assume the liability of the bank. 10. See CBN Macroprudential Guidelines (2010) for details.11. According to the authors, the figure is the cleaner sample from which inferences are drawn.12. Although literature search shows another new dimension to the determination of the concept of market discipline, “Currency Shift”. This approach would be considered in our next research (See Semenova and Andrew, 2016) for additional information.13. See also Maechler and McDill (2006).14. Of course, the likely inertia in the dependent variable gives room for the use of lagged dependent variables at the right hand side (RHS) of the equation.15. See Yaaba and Idris (2015) and Yaaba (2016) for detail.16. Broad liquid asset equals the core assets plus securities that are traded in liquid markets and can be easily converted into cash with no or minimal change in value.17. Test of over-identifying restrictions.18. This indicates that the instruments are jointly uncorrelated with error term, hence the model can be said not to be badly specified.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML