Beatrice Njeri Mwangi1, Samwel N. Mwenda2

1Faculty of Business studies, Department of business administration, Chuka University, Chuka, Kenya

2Deparment of Data processing, Kenya National Bureau of statistics, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Beatrice Njeri Mwangi, Faculty of Business studies, Department of business administration, Chuka University, Chuka, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

A booming interest in the topic of international remittances has developed over the past few years on the part of academics, donors, international financial institutions, commercial banks, money transfer operators, microfinance institutions, and policy makers. The surge of remittances to countries of origin in the last two decades and foreign direct investment (FDI) to developing countries, has reignited debate on their development potential in receiving countries. Alongside the interest in remittances, there is also growing recognition of the importance of transnational practices in shaping the relationship between migration and remittances. The 2003 World Bank report noted that remittances are more stable than other kinds of external financial flows and indeed seem to be counter cyclical. The main objective this study was to determinate the effect of international remittances on the economic growth in Kenya. The study also investigated the causality between international remittances and economic growth. The data used was sourced from World Bank’s Development Indicators for the period 1993 to 2013. The study used Granger Causality to investigate the causality between international remittances on economic growth in Kenya. The ordinary least squares estimation was used to determine the effect of international remittances on economic growth. From the discussion of the findings above, it can be concluded that the international remittances indicators are significant factors influencing the economic growth in Kenya. Thus it can be concluded that economic growth in the Kenya is largely driven by international remittances.

Keywords:

Granger Causality, International remittances, Economic growth, Kenya

Cite this paper: Beatrice Njeri Mwangi, Samwel N. Mwenda, The Effect of International Remittances on Economic Growth in Kenya, Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2015, pp. 15-24. doi: 10.5923/j.m2economics.20150301.03.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

International migration has become a strategy for individuals and families in developing countries such as Kenya to cope with poverty and economic crisis. Migrants attempt not only to improve their own livelihoods but they send a considerable share of their earnings to their families in the region of origin as remittances. The importance of international migration is evidenced by the numerous money transfer institutions and the rapid increase in international remittances. Migrants maintain a link with countries of origin through a complex network of cultural, economic, social and political relations, which can be sustained through new technologies and cheaper travel.The trend of mounting international remittances in Kenya is likely to continue as more and more Kenyans are still seeking for work and study opportunities in different locations both national and international. Remittances rose from US$ 7,260,000 in 1970 to US$ 89, 099,998 in 1989. By 2009, remittances were US$ 609,156 million [1]. Remittances inflow remained resilient in the 12 months to august 2014, with the cumulative flow having increased by 12.4 percent in 2013.The 12 month average flow during the same period sustained an upward trend to peak as US$ 115.3 million from an average of US$ 102.6 million [2]. The steady rise in remittances is attributed to the rise of the number of Kenyans in the Diaspora. The Kenyan Embassy in Washington D. C. indicated that by July, 2011 there were three million Kenyans in the Diaspora and in the USA alone, there were about 400,000 Kenyans. The passing of the new constitution in 2010 which allowed for dual citizenship has made those Kenyans who would wish to invest both in the countries they live and at home to increase remittances [3]. Lastly, there has been an aggressive campaign by the Kenya Government to involve the Kenyan Diaspora in the development agenda of the country. Government’s ratification of the amendment to the African Union (AU) Constitutive Act Article 3(q) that invites and encourages the full participation of the African Diaspora as an important part of African continent’s building [4].Kenya’s GDP growth was high in the first two decades after independence in 1963. This was due to public investment, encouragement of small holder agricultural production and incentives for private investment. There was notable decline in Kenya’s economic performance from the 1970s to 2004 when GDP growth was below 10 percent. This was due to the adverse weather conditions and the general elections. Also the period of 1974-1990 coincided with high oil prices which made Kenya’s manufacturing sector uncompetitive. GDP expanded by 4.7 percent in the year 2013 over the previous year and annual Growth Rate averaged to 4.8 Percent from 2004 to 2013, reaching an all time high of 7.0 Percent in 2007 and a low record of 1.5 percent in 2008 [5]. International remittances are transferred through formal and informal mechanisms. The main formal remittances services providers (RSPs) are money-transfer operators (MTOs), the banks and post offices, microfinance institutions (MFIs) and new transaction technology (NTT) mechanisms, including mobile network operators (MNOs). Formal channels are particularly important since they can serve as an entry point to formal financial inclusion by facilitating and expanding access to other financial products and services, in both origin and destination countries (Agunias and Newland, 2012; Gupta, Pattillo and Wagh, 2009). Hawala is one of the most widespread informal money transfer tools. Originating in South Asian societies, it emerged as a system for debt transfer to facilitate long distance and cross-border trades, especially within a framework of imperfect legal context without sufficient payments methods. The basic hawala mechanism works in the following way: the remitter pays, often with a small fee, the first transfer person (in the sending country), who informs the second transfer person (in the recipient country), and the second transfer person releases the funds to the recipient.An increasing interest in the topic of international remittances has developed over the past few years on the part of academics, donors, international financial institutions, commercial banks, money transfer operators, microfinance institutions and policy makers. Some scholars believe that international remittances have positive growth effects in recipient economies [6], while other scholars highlight the negative growth effects of remittances [7]. The latter argue that remittances do not result in positive economic growth since the two variables are negatively correlated.There are also scholars who claim that remittances have no impact on economic growth of recipient countries [8]. For these scholars, there is no causal relationship between remittances and economic growth of developing countries. Some countries receiving large amounts of remittances (e.g. the Philippines, Ecuador and Yemen) have performed rather poorly and yet some others with large remittances inflows for example (China, India and Thailand) have performed rather well [9].

1.2. Statement of Problem

Remittances are a source of inflow of cash, increasing national income considerably. The available empirical evidence is highly conflicted and to some extent they are informed by the available theoretical literature conversing on the ways through which remittances impact economic growth. Examination of the role of international remittances in economies still faces a challenge of the quality and coverage of data in several countries. There is no universal agreement on how to measure the impact of international remittances to developing countries. These data limitations are attributed to improper procedure of capturing remittance statistics. Also variables of economic growth are also not agreeing for many researchers. All these give the need to keenly analyze and understand the possible effect of international remittance on the economic growth in Kenya.

1.3. Objective of the Study

The main objective of this study is to investigate the effect of international remittance on economic growth in Kenya. The specific objectives are: i. To examine the effect of international remittances on economic growth in Kenya.ii. To test the causal relationship between international remittances and economic growth in Kenya.iii. To draw policy recommendations based on (i) and (ii) above.

1.4. Research Hypothesis

HO1: International remittances have no significant effect on economic growthHO2: There is no significant causal relationship between international remittances and economic growth

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction

This chapter reviews theoretical literature and empirical literature. The first section deals with theoretical underpinnings of the effect of international remittances to economic growth. The second section reviews empirical evidence on the effect of international remittances on economic growth.

2.2. Theoretical literature

The Solow modelThe theory is based on neo-classical assumptions and assumes a multifactor production function including labour and capital which are assumed to be close substitutes. It assumes that the production function is increasing in each input, and has diminishing marginal product. When zero units of input are used for either K or L, then nothing is produced thus  . Also the production function exhibits constant returns to scale such that:

. Also the production function exhibits constant returns to scale such that:  . The Solow Model consists of two equations: a production function and a capital accumulation equation [10].The production function is given by:

. The Solow Model consists of two equations: a production function and a capital accumulation equation [10].The production function is given by:  .Y is output, K is capital and L is labour. Capital stocks include plant and machinery, bridges, factories, land just to mention but a few and labour represents economically active population. Consequently, for an economy to grow based on this model there must be an increment in the stocks of capital through investment and supply of labour through population growth. Investment on capital stock depends on savings and remittance can be used as substitute or to increase the domestic fund hence increase in capital funds. Furthermore, future remittance inflow can improve the creditworthiness of domestic investors, which may result into lower cost of capital in remittance receiving economies.The Endogenous Growth Models:It is an extension of Solow growth model. The objective was to explain how technological progress and economic growth become self sustaining. In the exogenous models the steady-state growth is determined exogenously, for example technical change. In the endogenous growth models, the steady-state growth is determined endogenously. In these models, one of the determinants of growth (Technology and labour employment) is assumed to grow automatically in proportion to capital. These models result in a production function of the form Y = AK and are thus called the AK models. Among the AK models are the Harrod-Domar and the Frankel-Rommer models.The Harrod-Domar ModelThis model seeks to establish the unique rate at which investment and income must grow so that full employment level is maintained. According to them, no economy can grow without investment which is determined by the level of total savings. The model is given as

.Y is output, K is capital and L is labour. Capital stocks include plant and machinery, bridges, factories, land just to mention but a few and labour represents economically active population. Consequently, for an economy to grow based on this model there must be an increment in the stocks of capital through investment and supply of labour through population growth. Investment on capital stock depends on savings and remittance can be used as substitute or to increase the domestic fund hence increase in capital funds. Furthermore, future remittance inflow can improve the creditworthiness of domestic investors, which may result into lower cost of capital in remittance receiving economies.The Endogenous Growth Models:It is an extension of Solow growth model. The objective was to explain how technological progress and economic growth become self sustaining. In the exogenous models the steady-state growth is determined exogenously, for example technical change. In the endogenous growth models, the steady-state growth is determined endogenously. In these models, one of the determinants of growth (Technology and labour employment) is assumed to grow automatically in proportion to capital. These models result in a production function of the form Y = AK and are thus called the AK models. Among the AK models are the Harrod-Domar and the Frankel-Rommer models.The Harrod-Domar ModelThis model seeks to establish the unique rate at which investment and income must grow so that full employment level is maintained. According to them, no economy can grow without investment which is determined by the level of total savings. The model is given as  where K is capital, S is saving, and Y is output. ∆Y/Y represents the rate of economic growth. Hence Harrod-Dommar model states that the rate of growth of GDP is determined jointly by the national savings ratio and national capital output ratio. This means the more economy saves and invest the more it grows. To achieve a higher economic growth, the savings rate must be higher. If the domestic savings are not enough, then foreign savings will be required so that they can be translated into investments to boost domestic economic growth.The Frankel-Rommer ModelThis model assumes that it is technological knowledge that grows automatically with capital. According to this model technological knowledge is itself some kind of capital good, implying that K is interpreted as an aggregate of different sorts of capital goods, where remittances are some of these aggregates. Assuming that all firms face the same technology and the same factor prices, Y=AKαL(1-α), Frankel (1962). Assume that the scale factor is a function of the overall capital/labour ratio, A=B (K/L)β.Taking a special case where

where K is capital, S is saving, and Y is output. ∆Y/Y represents the rate of economic growth. Hence Harrod-Dommar model states that the rate of growth of GDP is determined jointly by the national savings ratio and national capital output ratio. This means the more economy saves and invest the more it grows. To achieve a higher economic growth, the savings rate must be higher. If the domestic savings are not enough, then foreign savings will be required so that they can be translated into investments to boost domestic economic growth.The Frankel-Rommer ModelThis model assumes that it is technological knowledge that grows automatically with capital. According to this model technological knowledge is itself some kind of capital good, implying that K is interpreted as an aggregate of different sorts of capital goods, where remittances are some of these aggregates. Assuming that all firms face the same technology and the same factor prices, Y=AKαL(1-α), Frankel (1962). Assume that the scale factor is a function of the overall capital/labour ratio, A=B (K/L)β.Taking a special case where  ,

,  Thus, once capital increases, output increases in the same proportion. The endogenous growth theory recognizes that for productivity to increase labour needs to be augmented with more resources. These resources include physical and human capital, and technology. This implies that for growth to occur there must be an accumulation of factors of production. Remittances are source of capital and are believed to have an impact on economic growth. The accelerator theoryThe accelerator model is also referred to as the Accelerator-Multiplier Model. It was first developed by an English economist, Roy Harrod (1900-1978) in 1939. According to this model a certain amount of capital is required to support a given level of economic activity. The model is presented as, K=kY, k>1. Investment represents change in capital stock such that; I=k∆Y where I is investment in time and ∆Y is the GDP in period. The role of international remittances in this model is understood in the context of the determinants of income, Y = I + C+ G + NX, where C, I, G and NX, are private consumption, private investment, government expenditure and net exports respectively.Now if we incorporate the remittances (REM) in the autonomous expenditure such that; A*=G+NX+REM, this leads to Y= (A*-kY)/ (1b (I-t)-k; Y=a (A*-kYt)) where ‘a’ is the multiplier which represents how a change in autonomous expenditure affects the equilibrium level of income. This equation shows how an autonomous shock (in this case an increase in capital stock out of an increase in remittances) will lead to an increase in income. Remittances have an effect on economic growth through “a” since they lead to a change in A*. This study borrows a lot from this model in answering research questions.Two gap model of economic growthThis was the work of Chenery and Bruno (1962) and Chenery and Strout (1966). According to this model, growth requires investment which in turn requires savings. Assuming that there is no government sector, Y = C + I + (X - M) where Y is GNP, C is Consumption, I is Investment (or Domestic Capital formation), X is Export and M is import. Since Y – C = S Where: S = Savings (domestic) then M – X = I – S, (M – X) is the foreign exchange gap while (I – S) is the savings gap. These two constitute two separate constraints. Eliminating one does not get rid of the other. If we let (M – X) = F, then we can represent the above as follows, I = F + S.Using the relationship posited above, the following scenarios may arise: Savings may be too small to permit the amount of investment that the country would otherwise have the capability to undertake. Therefore, a savings gap would exist. Export may be too small to permit the import required to make full use of the resources of the economy. Therefore a foreign exchange (or trade) gap would exist. While the two gaps are distinct and separate ones, international remittances can, in fact, be used to fill both. For example international remittances can increase domestic savings and also households receiving them may use for agriculture and business which will increase the exports.Three gap modelAccording to the three-gap model, the utilization and expansion of existing productive capacity is constrained not only by domestic and foreign savings, as was initially discussed by Chenery and Strout (1966) in the context of the two-gap model, but also by the impact of fiscal limitations on government spending and thus on its public investment choices.

Thus, once capital increases, output increases in the same proportion. The endogenous growth theory recognizes that for productivity to increase labour needs to be augmented with more resources. These resources include physical and human capital, and technology. This implies that for growth to occur there must be an accumulation of factors of production. Remittances are source of capital and are believed to have an impact on economic growth. The accelerator theoryThe accelerator model is also referred to as the Accelerator-Multiplier Model. It was first developed by an English economist, Roy Harrod (1900-1978) in 1939. According to this model a certain amount of capital is required to support a given level of economic activity. The model is presented as, K=kY, k>1. Investment represents change in capital stock such that; I=k∆Y where I is investment in time and ∆Y is the GDP in period. The role of international remittances in this model is understood in the context of the determinants of income, Y = I + C+ G + NX, where C, I, G and NX, are private consumption, private investment, government expenditure and net exports respectively.Now if we incorporate the remittances (REM) in the autonomous expenditure such that; A*=G+NX+REM, this leads to Y= (A*-kY)/ (1b (I-t)-k; Y=a (A*-kYt)) where ‘a’ is the multiplier which represents how a change in autonomous expenditure affects the equilibrium level of income. This equation shows how an autonomous shock (in this case an increase in capital stock out of an increase in remittances) will lead to an increase in income. Remittances have an effect on economic growth through “a” since they lead to a change in A*. This study borrows a lot from this model in answering research questions.Two gap model of economic growthThis was the work of Chenery and Bruno (1962) and Chenery and Strout (1966). According to this model, growth requires investment which in turn requires savings. Assuming that there is no government sector, Y = C + I + (X - M) where Y is GNP, C is Consumption, I is Investment (or Domestic Capital formation), X is Export and M is import. Since Y – C = S Where: S = Savings (domestic) then M – X = I – S, (M – X) is the foreign exchange gap while (I – S) is the savings gap. These two constitute two separate constraints. Eliminating one does not get rid of the other. If we let (M – X) = F, then we can represent the above as follows, I = F + S.Using the relationship posited above, the following scenarios may arise: Savings may be too small to permit the amount of investment that the country would otherwise have the capability to undertake. Therefore, a savings gap would exist. Export may be too small to permit the import required to make full use of the resources of the economy. Therefore a foreign exchange (or trade) gap would exist. While the two gaps are distinct and separate ones, international remittances can, in fact, be used to fill both. For example international remittances can increase domestic savings and also households receiving them may use for agriculture and business which will increase the exports.Three gap modelAccording to the three-gap model, the utilization and expansion of existing productive capacity is constrained not only by domestic and foreign savings, as was initially discussed by Chenery and Strout (1966) in the context of the two-gap model, but also by the impact of fiscal limitations on government spending and thus on its public investment choices.

2.3. Empirical Literature

There are only few empirical studies that have analyzed the relation between remittances and growth. The empirical studies show that remittances can stimulate economic activity and motivate entrepreneurial communities [11]. Remittances help households move out of poverty [12] and increase educational and housing spending [13]. Chami et al uses panel data to study the moral hazard effect framework on remittance’s motivation and their effect on economic activity. They find a negative effect of remittances on economic growth [14].Glytsos analyzes the effect of remittances on investment, consumption, imports and output. The author uses a sample of five countries and estimates short and long run multipliers of remittances. He finds that the effect of reducing remittances would be greater than the effect of raising them [15]. Giuliano and Ruiz-Arranz finds a positive effect of remittances on growth, specifically for countries with lower financial development [16]. Ziesemer proposes a savings channel that relates remittances with growth. He finds that remittances have a positive impact on growth, due to its ability to increase saving rates in countries with a per capita income of less than US $1200 [17]. The IMF undertook a cross-country growth regression by taking a sample of 101 countries with data ranging over 1970 – 2003 periods and took an aggregate measure of remittances which include the sum total of three components – workers’ remittances, compensation of employees and migrant transfers of the balance of payments. The IMF study performed cross-sectional growth regression of real GDP growth per capita on ratio remittances to GDP. The additional control variables included log of initial income, education, log of life expectancy, investments, inflation rate, budget balance, trade openness and financial development. The study also used two instruments for remittances. These include distance between the migrants’ home and main destination country, and a dummy measuring whether the home and the main destination country shared a common language. Since these instruments are time invariant, panel estimation was not undertaken rather a cross-sectional estimation over the averages of 1970 – 2003 was done. Using this cross-country growth regression framework, no significant link was found between real par- capita GDP growth and remittances [18].Faini estimated cross-sectional growth regressions on a sample of 68 countries where the dependent variable is per capita GDP growth. Using aggregate measure of remittances data in IMF (2005) the study did not include investment in the list of regressors. He noted that the positive impact of remittances on growth usually work through investments. So including it in the regression may render the effects of remittances insignificant as the investment’s coefficient could be capturing some of the effects. Along with remittances to GDP ratio, the control variables used were initial per capita GDP, secondary school enrolment (as a measure of human capital), the number of telephone lines per 1000 inhabitants (as an indicator of physical capital) and the International Country Risk Guide index as an indicator of institutional quality. The estimated coefficient on the remittances to GDP ratio was found to be positive and significant in the OLS regressions of the study. Later foreign aid to GDP ratio was included as additional control variable and remittance was still found to be positively affecting growth [19].The study by Guiliano and Ruiz-Arranz (2006) took a sample of 73countries during the 1975 – 2002 period. Aggregate measure of remittances was chosen as sum of all three categories on the balance of payments as in IMF (2005). In the paper of GRA remittance was found to strongly and robustly affecting growth through its interacting effect with the financial sector of the economy. The World Bank study conducted a panel data estimates on the impact of remittances and growth using a sample of 67 countries measured over the period of 1991– 2005. The control variables used were (all in logs) initial GDP per capita, secondary school enrolment ratio, the private domestic credit to GDP ratio, ICRG political risk index, real export and import to GDP ratio, inflation rate, real exchange rate overvaluation, government consumption, and time period dummies. The regression specifications found a positive and significant relationship between remittances to GDP ratio and per capita GDP growth. The magnitude of the estimated effect of remittances on growth was found to relatively small in economic terms. Increase in remittance to GDP ratio from 0.7 percent to 2.3 percent is estimated to have led to an increase in 0.27 percent increase in GDP growth. However, when the investment to GDP ratio is included along with the rest of control variables, the estimated coefficient on remittances to GDP looses significance. This led the study to conclude that one of the main channels through which remittances work is through increasing domestic investment [20]. Few studies have been done on the impact of remittances on economic growth in Kenya. Kirigia and Oyelere found that Kenya had experienced significant brain drain and waste, though at a decreasing rate, especially in the health sector, where they noted that Kenya loses approximately about US$ 517,931 and US$ 338,868 worth of return in investment, respectively, for every doctor and nurse who emigrates [21] and [22]. Kiiru (2010) found a positive and significant effect on reduction of poverty in Kenya.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Processing and Pre-estimation Diagnostics

Data from the World Bank Development Indicators on remittances, trade openness and government expenditure were in US dollars. Some of the series were non-stationary. This necessitated the addition of logs of these variable were taken which yielded stationary series.

3.2. Test for Stationarity

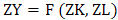

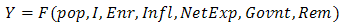

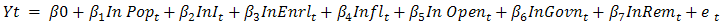

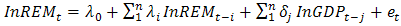

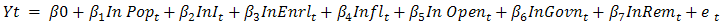

In order to avoid the possibility of biased results emanating from a likely existence of unit roots in the variables under study, the researcher performed stationarity test using the ADF (Augmented Dickey Fuller) test procedure. The ADF assumes that the error terms are independently and identically distributed.Model specificationSince the main objective of the study is to analyze the impact of international remittances on economic growth in Kenya, this was achieved through Ordinary Least Squares estimation. The Ordinary Least Squares estimation included other determinants of economic growth. These variables were selected on the basis that they have been identified in the literature as determinants of economic growth. The effect of international remittance on economic growth in Kenya was captured by running an ordinary least squares estimation of the following equation | (1) |

| (2) |

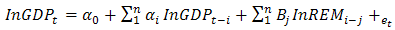

Y is the dependent variable, economic growth. β0 is the constant. β1, β2, ------, β7 are the regression coefficients which determines the contribution of the independent variables. P op is the population growth, I is investment, Enrl represents human capital, percentage in gross secondary education enrolment was used as a proxy for human capital. Infl is inflation, Openis openness, expressed as the percentage of the total value of export plus imports as a share of GDP. Govt is government consumption which was expressed using data for general government final consumption expenditure as a percentage of GDP. Rem is real per capita international remittance an de = error (or residual) value. Growth of real per capita GDP was used as a measure for economic growth and the gross fixed capital formation divided by GDP as a measure of investment.The second objective was to determine the causality between international remittances and economic growth hence granger causality test was used. Granger Causality is a statistical hypothesis test for determining whether one time series is useful in forecasting another (Granger, 1969). That is a time series X is said to Granger cause Y if it can be shown that X values provide statistically significant information about future values of Y. If a time series is stationary, then the test is performed using the level values of two (or more) variables. The log of the series was I(0), thus the following set of equations was estimated: | (3) |

| (4) |

Where n is the maximum number of lagged observations included in the model, α’s, β’s, λ’s and δ’s are parameters, and lnGDP is the log of GDP growth. lnREM is the log of international remittances. (3) Postulates that current economic growth is related to past values of itself as well as those of for international remittances. Similarly, (4) postulates that international remittances are related to their past values as well as those of economic growth.

4. Data Compilation, Analysis and Presentation

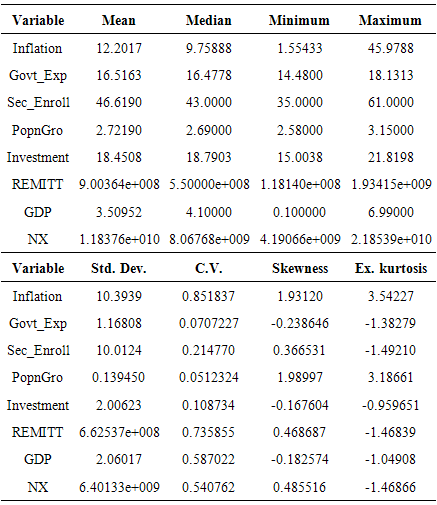

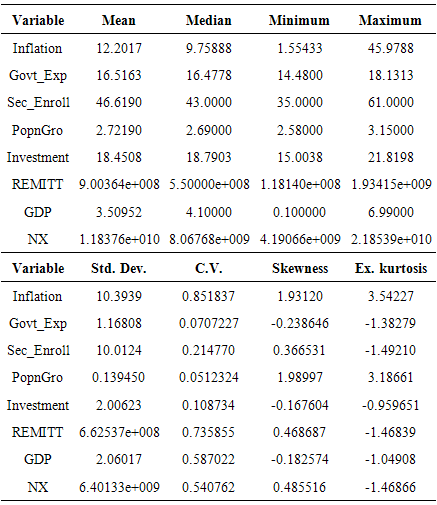

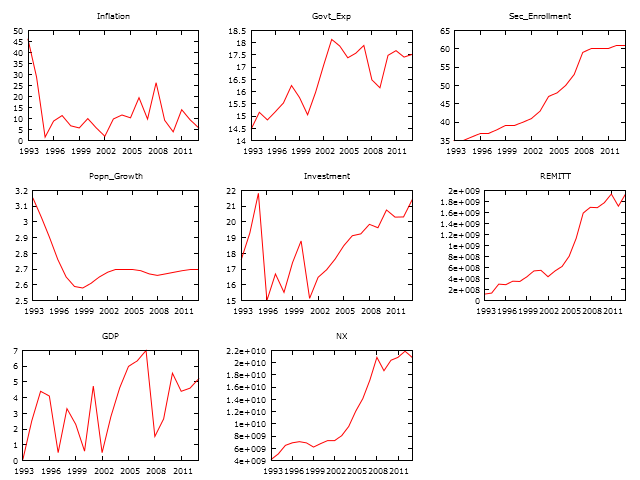

The estimation of the model and other diagnostic tests are done using Gretl. First descriptive statistics was used to view the overall structure of the variables in question. The unit root tests are conducted in order to identify the time series characteristics of the variables and finally the Ordinary Least Squares method was used to test the significance relationship between the variables for our model and Granger causality test performed on the variables aforementioned. The summary statistics for international remittances, inflation, economic openness, investment, secondary enrollment, population growth, government expenditure and GDP are given in table 1. Table 1. Summary Statistics, using the observations 1993 – 2013

|

| |

|

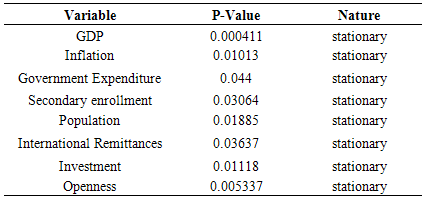

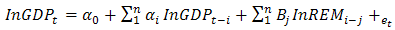

Table 2. Stationarity Test

|

| |

|

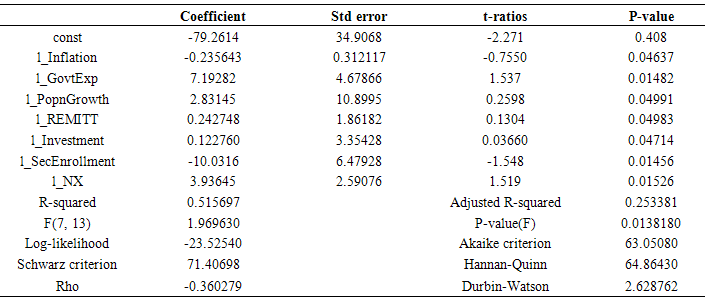

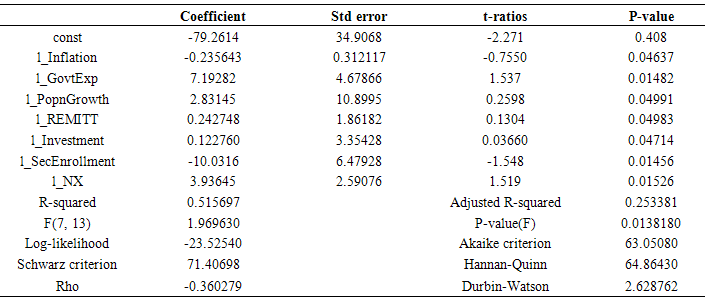

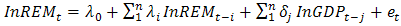

ADF Unit Root Test (Logged form) Government Expenditure, Secondary enrollment, International remittances, Investment and economic oppeness were all found not stationery in their level form because the ADF (p-values) of all the variables were greater than the fixed 5 percent level of significance. The natural log of GDP, Inflation, Population, Secondary enrollment, Investment, International remittances were found Stationary because the ADF (p-value) were less 5 percent level of significance. Hence there was no presence of a unit root on the log form of variables.Dependent variable: l_GDPResults from the regression analysis (Table 3) indicate that the government expenditure, population growth, economic openness, remittance, and investment impact positively on the GDP; while secondary school enrollment and inflation have negative effect on economic growth. The probability F-statistic is 0.0138180 (<0.05), indicate that the explanatory variables are jointly significant in explaining the model and therefore a good model. the R ^2 = 0.515697 shows that our model fits the data well and explains over 52% of the variation.

Government Expenditure, Secondary enrollment, International remittances, Investment and economic oppeness were all found not stationery in their level form because the ADF (p-values) of all the variables were greater than the fixed 5 percent level of significance. The natural log of GDP, Inflation, Population, Secondary enrollment, Investment, International remittances were found Stationary because the ADF (p-value) were less 5 percent level of significance. Hence there was no presence of a unit root on the log form of variables.Dependent variable: l_GDPResults from the regression analysis (Table 3) indicate that the government expenditure, population growth, economic openness, remittance, and investment impact positively on the GDP; while secondary school enrollment and inflation have negative effect on economic growth. The probability F-statistic is 0.0138180 (<0.05), indicate that the explanatory variables are jointly significant in explaining the model and therefore a good model. the R ^2 = 0.515697 shows that our model fits the data well and explains over 52% of the variation.Table 3. OLS, using observations 1993-2013 (T = 21)

|

| |

|

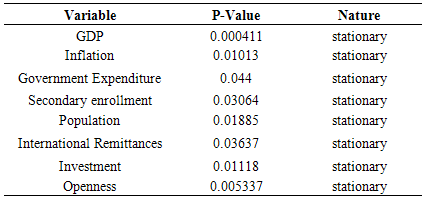

Table 4. Granger Causality Test

|

| |

|

Granger causality test was carried out at 5% level of significance. The null hypothesis of no Granger causality is rejected when the p-value is less than the fixed level of significance. From table 4 above its apparent that there is significant bi-directional causal relationship between GDP and remittances. This implies that a movement in GDP will cause a corresponding movement in remittances which also has the same effect on GDP. There also exist a uni-directional causality running from GDP to government expenditure.

5. Summary, Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Summary

The question as to whether it is remittances inflows that promote economic growth or if it is economic growth that attracts international remittances inflows has not been investigated in Kenya. This study analyzed the relationship between international remittances and other factors to economic growth. Specifically, the study investigated the effect of international remittances on economic growth. Secondly the study investigated causality between international remittances and economic growth.The study used Granger Causality to investigate the relationship between international remittances and economic growth. The ordinary least squares estimation was used to determine the effects of international remittances on economic growth. The study included other determinants of economic growth in the ordinary least squares estimation of the economic growth equation. Time series data was sourced from the World Bank’s development indicators, the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and the Central Bank of Kenya for the period 1993 to 2013. The study found that there was a bi-directional causality from international remittances to economic growth and GDP to international remittances.The coefficient of international remittances was positive and statistically significant. This suggests that remittances inflow plays an important role in Kenya’s economic growth. Investment as a ratio of GDP was found to have a positive and statistically significant coefficient. The coefficient of government expenditure on goods and services as a ratio of GDP was found positive and statistically significant. This implies that government expenditure if well managed can have a positive impact on the economic growth of Kenya. The coefficient of secondary enrolment which was used as a proxy for human capital was negative and statistically significant. Educated labour force has a positive impact on the economic growth, the negative effect may be as a result of fees spend by parents or the quality of education provided.The coefficient of inflation which was used as a proxy for macroeconomic stability was negative and statistically significant. This implies that inflation has a negative impact on the economic growth. The coefficient of sum of total exports and total imports which was used as a proxy for openness was positive and statistically significant. This indicates that openness plays an important role to economic growth in Kenya. Coefficient of population growth was positive meaning the higher population the higher economic growth.

5.2. Conclusions

This study has established that remittances have a positive impact on economic growth. There is a Bi-directional causality from international remittances to economic growth and economic growth to international remittances. Consistent with existing literature, this study has established that economic openness, government expenditure, investment and population have a positive and statistically significant effect on economic growth in Kenya. On the other hand, secondary enrollment and inflation had a negative impact on economic growth.

5.3. Policy Implications

The Government of Kenya should work towards an environment that attracts international remittances. This is in line with this study’s findings that international remittances as a ratio of GDP granger cause economic growth and that, international remittances as a ratio of GDP has a positive and statistically significant coefficient. The establishment of the International Jobs and Diaspora Office in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is a good step in the right direction in boosting remittances. But the Office should work with the Ministry of Interior and Coordination of National Government to tap into new markets for the Kenyan labour especially in the East African Community and the Middle East so as to increase the remittances in the future. In addition, the Government should put in place institutions to help recipients of remittances to make the most use of these funds and provide information to the Kenyan Diaspora on the investible opportunities available so that the remittances can be put into productive use.The Government of Kenya should continue to pursue a high and sustainable economic growth rate to attract remittances inflow. This is in line with findings of the study that economic growth granger cause remittances inflows. Remittances are likely to have a positive growth effect for a particular country when they are used to acquire locally produced products. Therefore there is a need for policies that protect local industries as far as remittances are concerned.The Government with its trading partners especially in the East African Community and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa should remove any trade barriers (for example the numerous road blocks, weigh bridges and border gates; lack of harmonization of documents and procedures; Visa charges for businessmen and length procedures in issuing work permits) that exist so that the volume of exports and imports increases. This is because this study has established that the sum total of exports and imports has a positive and significant coefficient. In addition the Government should encourage export oriented industries so that the net exports will increase, making the country earn more of the much needed foreign exchange. This will free the country from the foreign exchange gap constraint. The government should also provide more resources for the improvement of quality of education. This is because the results show that secondary enrolment as ratio of the total population has a negative and significant coefficient. The provision of free primary and secondary education which began in 2003 and 2008 respectively was a move in the right direction. An effort should be made to make sure that basic education is truly free to bring more children to school and enable parents use their income for other investment instead of paying fee. This can be done by providing children with school uniform, providing sanitary towels to girls and introducing a feeding programme especially in the arid and semi arid areas among other actions. With the expansion of basic education, there is need to provide more opportunities for higher education by expanding middle level colleges and universities. The current elevation of existing university colleges into fully fledged universities is encouraged as it opens up more opportunities to train the labour force. However, it should not be forgotten that the country needs middle level manpower. As these middle level colleges are being upgraded into university colleges and eventually fully fledged universities there should be established new middle level colleges to replace them. An educated labour force would contribute to the economic growth of the country because it is expected that it has more skills and is thus more productive. The Kenya Government through the National Treasury and Central Bank should also endeavor to maintain macroeconomic stability because this study has shown that inflation has a negative effect on economic growth. In all, both the fiscal and monetary policies should aim at keeping the inflation rate at a single digit, maintaining low interest rates and a stable exchange rate. This will be an incentive to private investors both local and foreign.

5.4. Contributions to Knowledge

This study has contributed to the understanding of the role of international remittances on economic growth. Additionally the study gives the effect of investment, economic openness, human capital, inflation, population growth and government expenditure on economic growth. The study has given an insight into the causality between international remittances and economic growth in Kenya.

5.5. Areas for Further Research

There are a number of areas that require further research. The study sought to investigate the impact of diaspora remittances on the economic growth. However the variables used in the study were not exhaustive. Future research could incorporate macroeconomic variables such as, exchange rates and interest rates. A study of what are the determinants of remittances will assist the Government to work on areas that will enhance the same. This study did not investigate the interaction between International remittances inflows and the other variables: for example, remittances and investment, remittances and openness, remittances and school enrollment as explanatory variables in the estimation of the effect of international remittances on Kenya’s economic growth as explanatory variables. A study that will include the interaction of these variables as explanatory variables of economic growth will complement this study. This will inform policy makers in deciding whether they need to pursue joint or separate policies regarding the variables which determine economic growth.

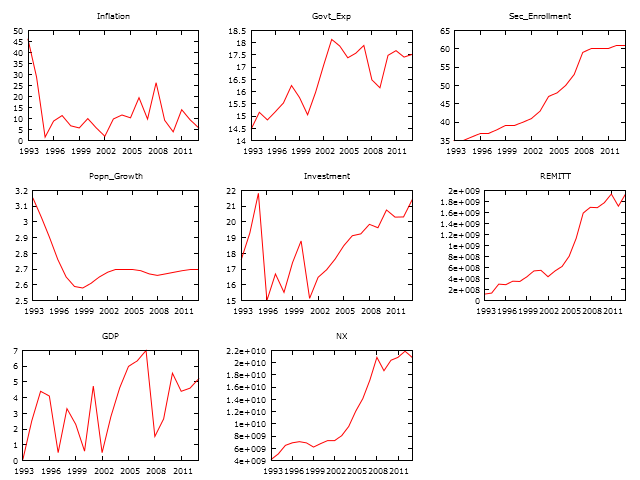

Appendix 1

| A Graph Showing Time Series Trend of the Variables |

References

| [1] | Central Bank of Kenya. (2011). Diaspora remittances. |

| [2] | Central Bank of Kenya. (2014). Diaspora Remittances. |

| [3] | Official law Reports of The Republic of Kenya. (2010). The Constitution of Kenya. National Council for Law Reporting. |

| [4] | The Constitutive Act. (2000). Retrieved March 23, 2015, from http://www.africa-union.org/roo/au/aboutau/constitute-act.pdf. |

| [5] | World Bank. (2010). World development indicators. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators. |

| [6] | Fayissa, B., & Nsiah, C. (2010). The impact of remittances on economic growth and development in Africa. American Economist , 55, 92-103. |

| [7] | Karagoz, k. (2009). Workers remittances and economic growth:evidence from Turkey. Journal of Yasar University , 4 (13), 1891-1908. |

| [8] | Rao, B., & Hassan, G. (2011). A panel data analysis of the growth effects of. Economic Modelling , 28, 701-709. |

| [9] | ILO. (2004). Towards a fair deal for migrant workers inglobal economy. Geneva. |

| [10] | serletis, p. (2007). The Demand For Money:Theoretical and Empirical approaches (Second edition ed.). New York. |

| [11] | Woodruff, C., & Zenteno, R. (2007). Migration networks and micro-enterprises in Mexico. Journal of development economics , 82 (2), 509–528. |

| [12] | Kiiru, M. (2010). Remittances and Poverty in Kenya. Retrieved March 25, 2015, from http://www.oecd.rog/dataoecd/61/46/38840502. |

| [13] | Adams, H. (2005). Remittances, Household Expenditure and Investment in Guatemala. World Bank - Development Research Group (DECRG). |

| [14] | Chami, R., Fullenkamp, C., & Jahjah, S. (2005). Are immigrant remittance flows a source of capital for development? IMF Staff Papers, 52. |

| [15] | Glytsos, N. P. (2005). The contribution of remittances to growth: A dynamic approach and empirical analysis. Journal of Economic Studies , 32 (6), 468 - 496. |

| [16] | Giuliano, P., & Ruiz-Arranz, M. (2009). Remittances, financial development and growth. Journal of Development Economics , 90, 144-152. |

| [17] | Ziesemer, T. (2007). Worker remittances, migration, accumulation and growth . UNU-MERIT Working Papers . |

| [18] | IMF. (2005). World Economic Outlook April 2005. Washington D.C, USA. |

| [19] | Faini, R. (2006). Migration and Remittances: The impact on the Country of Origin. |

| [20] | The World Bank. (2006). Global Economic Prospects 2006. Washington D.C, USA. |

| [21] | Oyelere, R. (2007). Brain Drain, Waste or Gain? What we know about the Kenyan case. Journal of Global Initiatives , 2 (2), 113-129. |

| [22] | Kirigia. (2006). The Cost of Health professionals brain drain in Kenya. |

| [23] | Alfaro, L. A.-O. (2004). Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth: The Role of Financial Markets. Journal of International Economics , 512-533. |

| [24] | Barajas, A. R. Do Workers Remittances Promote Economic Growth? IMF Working Papers. 09. |

| [25] | Chenery, H., & A, M. S. (1966). Foreign Assistance and Economic Development. America Economic Review , 56, 679-733. |

| [26] | Chenery, H., & M, B. (1962). Development Alternatives in an Open Economy:The case of Israel. 72, 79-103. |

| [27] | Lowenstein, B. D. (2005). Two-Gap Models: Post-Keynesian Death and Neoclassical Rebirth. Institute of Development, Research and Development Policy, Bochum. IEE Work Papers , 180. |

| [28] | Union, A. (2000). The Constitutive Act, Retrieved from http://www.africa-union.org/roo/au/aboutau/constitute-act.pdf on 17/02/12. |

. Also the production function exhibits constant returns to scale such that:

. Also the production function exhibits constant returns to scale such that:  . The Solow Model consists of two equations: a production function and a capital accumulation equation [10].The production function is given by:

. The Solow Model consists of two equations: a production function and a capital accumulation equation [10].The production function is given by:  .Y is output, K is capital and L is labour. Capital stocks include plant and machinery, bridges, factories, land just to mention but a few and labour represents economically active population. Consequently, for an economy to grow based on this model there must be an increment in the stocks of capital through investment and supply of labour through population growth. Investment on capital stock depends on savings and remittance can be used as substitute or to increase the domestic fund hence increase in capital funds. Furthermore, future remittance inflow can improve the creditworthiness of domestic investors, which may result into lower cost of capital in remittance receiving economies.The Endogenous Growth Models:It is an extension of Solow growth model. The objective was to explain how technological progress and economic growth become self sustaining. In the exogenous models the steady-state growth is determined exogenously, for example technical change. In the endogenous growth models, the steady-state growth is determined endogenously. In these models, one of the determinants of growth (Technology and labour employment) is assumed to grow automatically in proportion to capital. These models result in a production function of the form Y = AK and are thus called the AK models. Among the AK models are the Harrod-Domar and the Frankel-Rommer models.The Harrod-Domar ModelThis model seeks to establish the unique rate at which investment and income must grow so that full employment level is maintained. According to them, no economy can grow without investment which is determined by the level of total savings. The model is given as

.Y is output, K is capital and L is labour. Capital stocks include plant and machinery, bridges, factories, land just to mention but a few and labour represents economically active population. Consequently, for an economy to grow based on this model there must be an increment in the stocks of capital through investment and supply of labour through population growth. Investment on capital stock depends on savings and remittance can be used as substitute or to increase the domestic fund hence increase in capital funds. Furthermore, future remittance inflow can improve the creditworthiness of domestic investors, which may result into lower cost of capital in remittance receiving economies.The Endogenous Growth Models:It is an extension of Solow growth model. The objective was to explain how technological progress and economic growth become self sustaining. In the exogenous models the steady-state growth is determined exogenously, for example technical change. In the endogenous growth models, the steady-state growth is determined endogenously. In these models, one of the determinants of growth (Technology and labour employment) is assumed to grow automatically in proportion to capital. These models result in a production function of the form Y = AK and are thus called the AK models. Among the AK models are the Harrod-Domar and the Frankel-Rommer models.The Harrod-Domar ModelThis model seeks to establish the unique rate at which investment and income must grow so that full employment level is maintained. According to them, no economy can grow without investment which is determined by the level of total savings. The model is given as  where K is capital, S is saving, and Y is output. ∆Y/Y represents the rate of economic growth. Hence Harrod-Dommar model states that the rate of growth of GDP is determined jointly by the national savings ratio and national capital output ratio. This means the more economy saves and invest the more it grows. To achieve a higher economic growth, the savings rate must be higher. If the domestic savings are not enough, then foreign savings will be required so that they can be translated into investments to boost domestic economic growth.The Frankel-Rommer ModelThis model assumes that it is technological knowledge that grows automatically with capital. According to this model technological knowledge is itself some kind of capital good, implying that K is interpreted as an aggregate of different sorts of capital goods, where remittances are some of these aggregates. Assuming that all firms face the same technology and the same factor prices, Y=AKαL(1-α), Frankel (1962). Assume that the scale factor is a function of the overall capital/labour ratio, A=B (K/L)β.Taking a special case where

where K is capital, S is saving, and Y is output. ∆Y/Y represents the rate of economic growth. Hence Harrod-Dommar model states that the rate of growth of GDP is determined jointly by the national savings ratio and national capital output ratio. This means the more economy saves and invest the more it grows. To achieve a higher economic growth, the savings rate must be higher. If the domestic savings are not enough, then foreign savings will be required so that they can be translated into investments to boost domestic economic growth.The Frankel-Rommer ModelThis model assumes that it is technological knowledge that grows automatically with capital. According to this model technological knowledge is itself some kind of capital good, implying that K is interpreted as an aggregate of different sorts of capital goods, where remittances are some of these aggregates. Assuming that all firms face the same technology and the same factor prices, Y=AKαL(1-α), Frankel (1962). Assume that the scale factor is a function of the overall capital/labour ratio, A=B (K/L)β.Taking a special case where  ,

,  Thus, once capital increases, output increases in the same proportion. The endogenous growth theory recognizes that for productivity to increase labour needs to be augmented with more resources. These resources include physical and human capital, and technology. This implies that for growth to occur there must be an accumulation of factors of production. Remittances are source of capital and are believed to have an impact on economic growth. The accelerator theoryThe accelerator model is also referred to as the Accelerator-Multiplier Model. It was first developed by an English economist, Roy Harrod (1900-1978) in 1939. According to this model a certain amount of capital is required to support a given level of economic activity. The model is presented as, K=kY, k>1. Investment represents change in capital stock such that; I=k∆Y where I is investment in time and ∆Y is the GDP in period. The role of international remittances in this model is understood in the context of the determinants of income, Y = I + C+ G + NX, where C, I, G and NX, are private consumption, private investment, government expenditure and net exports respectively.Now if we incorporate the remittances (REM) in the autonomous expenditure such that; A*=G+NX+REM, this leads to Y= (A*-kY)/ (1b (I-t)-k; Y=a (A*-kYt)) where ‘a’ is the multiplier which represents how a change in autonomous expenditure affects the equilibrium level of income. This equation shows how an autonomous shock (in this case an increase in capital stock out of an increase in remittances) will lead to an increase in income. Remittances have an effect on economic growth through “a” since they lead to a change in A*. This study borrows a lot from this model in answering research questions.Two gap model of economic growthThis was the work of Chenery and Bruno (1962) and Chenery and Strout (1966). According to this model, growth requires investment which in turn requires savings. Assuming that there is no government sector, Y = C + I + (X - M) where Y is GNP, C is Consumption, I is Investment (or Domestic Capital formation), X is Export and M is import. Since Y – C = S Where: S = Savings (domestic) then M – X = I – S, (M – X) is the foreign exchange gap while (I – S) is the savings gap. These two constitute two separate constraints. Eliminating one does not get rid of the other. If we let (M – X) = F, then we can represent the above as follows, I = F + S.Using the relationship posited above, the following scenarios may arise: Savings may be too small to permit the amount of investment that the country would otherwise have the capability to undertake. Therefore, a savings gap would exist. Export may be too small to permit the import required to make full use of the resources of the economy. Therefore a foreign exchange (or trade) gap would exist. While the two gaps are distinct and separate ones, international remittances can, in fact, be used to fill both. For example international remittances can increase domestic savings and also households receiving them may use for agriculture and business which will increase the exports.Three gap modelAccording to the three-gap model, the utilization and expansion of existing productive capacity is constrained not only by domestic and foreign savings, as was initially discussed by Chenery and Strout (1966) in the context of the two-gap model, but also by the impact of fiscal limitations on government spending and thus on its public investment choices.

Thus, once capital increases, output increases in the same proportion. The endogenous growth theory recognizes that for productivity to increase labour needs to be augmented with more resources. These resources include physical and human capital, and technology. This implies that for growth to occur there must be an accumulation of factors of production. Remittances are source of capital and are believed to have an impact on economic growth. The accelerator theoryThe accelerator model is also referred to as the Accelerator-Multiplier Model. It was first developed by an English economist, Roy Harrod (1900-1978) in 1939. According to this model a certain amount of capital is required to support a given level of economic activity. The model is presented as, K=kY, k>1. Investment represents change in capital stock such that; I=k∆Y where I is investment in time and ∆Y is the GDP in period. The role of international remittances in this model is understood in the context of the determinants of income, Y = I + C+ G + NX, where C, I, G and NX, are private consumption, private investment, government expenditure and net exports respectively.Now if we incorporate the remittances (REM) in the autonomous expenditure such that; A*=G+NX+REM, this leads to Y= (A*-kY)/ (1b (I-t)-k; Y=a (A*-kYt)) where ‘a’ is the multiplier which represents how a change in autonomous expenditure affects the equilibrium level of income. This equation shows how an autonomous shock (in this case an increase in capital stock out of an increase in remittances) will lead to an increase in income. Remittances have an effect on economic growth through “a” since they lead to a change in A*. This study borrows a lot from this model in answering research questions.Two gap model of economic growthThis was the work of Chenery and Bruno (1962) and Chenery and Strout (1966). According to this model, growth requires investment which in turn requires savings. Assuming that there is no government sector, Y = C + I + (X - M) where Y is GNP, C is Consumption, I is Investment (or Domestic Capital formation), X is Export and M is import. Since Y – C = S Where: S = Savings (domestic) then M – X = I – S, (M – X) is the foreign exchange gap while (I – S) is the savings gap. These two constitute two separate constraints. Eliminating one does not get rid of the other. If we let (M – X) = F, then we can represent the above as follows, I = F + S.Using the relationship posited above, the following scenarios may arise: Savings may be too small to permit the amount of investment that the country would otherwise have the capability to undertake. Therefore, a savings gap would exist. Export may be too small to permit the import required to make full use of the resources of the economy. Therefore a foreign exchange (or trade) gap would exist. While the two gaps are distinct and separate ones, international remittances can, in fact, be used to fill both. For example international remittances can increase domestic savings and also households receiving them may use for agriculture and business which will increase the exports.Three gap modelAccording to the three-gap model, the utilization and expansion of existing productive capacity is constrained not only by domestic and foreign savings, as was initially discussed by Chenery and Strout (1966) in the context of the two-gap model, but also by the impact of fiscal limitations on government spending and thus on its public investment choices.

Government Expenditure, Secondary enrollment, International remittances, Investment and economic oppeness were all found not stationery in their level form because the ADF (p-values) of all the variables were greater than the fixed 5 percent level of significance. The natural log of GDP, Inflation, Population, Secondary enrollment, Investment, International remittances were found Stationary because the ADF (p-value) were less 5 percent level of significance. Hence there was no presence of a unit root on the log form of variables.Dependent variable: l_GDPResults from the regression analysis (Table 3) indicate that the government expenditure, population growth, economic openness, remittance, and investment impact positively on the GDP; while secondary school enrollment and inflation have negative effect on economic growth. The probability F-statistic is 0.0138180 (<0.05), indicate that the explanatory variables are jointly significant in explaining the model and therefore a good model. the R ^2 = 0.515697 shows that our model fits the data well and explains over 52% of the variation.

Government Expenditure, Secondary enrollment, International remittances, Investment and economic oppeness were all found not stationery in their level form because the ADF (p-values) of all the variables were greater than the fixed 5 percent level of significance. The natural log of GDP, Inflation, Population, Secondary enrollment, Investment, International remittances were found Stationary because the ADF (p-value) were less 5 percent level of significance. Hence there was no presence of a unit root on the log form of variables.Dependent variable: l_GDPResults from the regression analysis (Table 3) indicate that the government expenditure, population growth, economic openness, remittance, and investment impact positively on the GDP; while secondary school enrollment and inflation have negative effect on economic growth. The probability F-statistic is 0.0138180 (<0.05), indicate that the explanatory variables are jointly significant in explaining the model and therefore a good model. the R ^2 = 0.515697 shows that our model fits the data well and explains over 52% of the variation. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML