-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

p-ISSN: 2168-457X e-ISSN: 2168-4588

2015; 3(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.m2economics.20150301.01

Bundling of Non-Complementary Products

Qing Hu

Graduate School of Economics, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan

Correspondence to: Qing Hu, Graduate School of Economics, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

We extend the model of Matutes and Regibeau (1988) to examine the incentive to bundle in both monopoly and duopoly market. Matutes and Regibeau (1988) assumed the products were complementary products in a duopoly market. Under the assumption of complementary products, bundling and independent pricing is same for a monopoly. In a duopoly market, independent pricing is always preferred. We extend their model by assuming the products are non-complementary. By adding the single product consumption, we find different results. In a monopoly market, when the reservation price is relatively small, independent pricing dominates bundling and the sum of the prices of the products under independent pricing is higher than the bundle price. If reservation price is high, the results are opposite. In addition, the market can never be fully served under bundling as reservation price increases. In a duopoly market, we find that bundling may be preferred.

Keywords: Bundling, Multiproduct firm, Reservation Price, Non-complementary products

Cite this paper: Qing Hu, Bundling of Non-Complementary Products, Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2015, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.m2economics.20150301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is commonplace to see several products sold as a combined product, say in a bundle. Firms in information, health care, telecommunication industries often offer products in bundles. Microsoft sells its word processor and spreadsheet in an office suite; many telecommunication companies sell the cables with their channels or services in bundles; Nintendo often offers the portable game console with a popular game in a single package. The problem of bundling attracts many economical researchers to discuss. Many studies on bundling for multiproduct firms consider the products are complementary, such as cameras and lenses, computers and software. The one element cannot be used without another element, thus consumers must buy the products together (eg., Matutes and Regibeau,1988; Gans, J., and King, S., 2005). However, we consider the products are non-complementary and we earn different results from the previous work.In Matutes and Regibeau (1988)’s model, they assumed there were two firms, A and B, selling two complementary system components, say, products 1 and 2. A consumer purchases at most one unit of each product. Therefore, when both firms engage in independent pricing, consumers have five options to select from, namely, AA, BB, BA, AB, and purchasing nothing. For example, AA means buying two components together from firm A, whereas AB means buying product 1 from firm A and product 2 from firm B. When both firms bundle, consumers have three purchasing options to select from, namely, AA, BB, and purchasing nothing. When only firm A bundles, because consumers must buy two components, the situation is the same as the one where both firms bundle. The researchers showed that independent pricing always dominated pure bundling. In this study, we assume products are non-complementary-for example, like coffee and sugar. We can find a bundle of coffee and sugar in supermarket stores. However, coffee and sugar are also sold separately. A consumer may purchase only coffee because he prefers drinking coffee without sugar. A consumer may also buy the bundle for a lower price. Therefore, consumers are allowed to purchase only a single product in this situation. Based on the setup of Matutes and Regibeau (1988), with the new assumption that products are non-complementary, when both firms engage in independent pricing, there are nine purchasing options: AA, BB, A1, A2, B1, B2, AB, BA, and purchasing nothing. When only firm A bundles, consumers have AA, BB, B1, B2, and purchasing nothing to select from, which is not equal to the situation where both choose to bundle. In our study, we find that pure bundling may dominate independent pricing. Moreover, we can analyze the monopoly market by extending the Matutes and Regibeau (1988)’s model. Based on the assumption that a monopoly holds non-complementary products, the incentive of bundling for a monopoly has been discussed and much of the work relies on the reservation price paradigm (e.g., Adams and Yellen 1976). However, different from the Hotelling model in Matutes and Regibeau (1988), Adams and Yellen (1976) built a two-dimensional model by assuming each axis represents consumers’ reservation price for either product. Consumers hold different level of reservation price for a product. In their result, they proved that whether bundling is more profitable depends on the distribution of customers in reservation price space. However, they concluded this by numerous experiments with continuous distribution of reservation prices and then they found that bundling dominates independent pricing in some occasions. In our two-dimensional Hotelling model, we can conclude the exact results by simple calculation, rather than numerous experiments. By adding the possibility of consuming one product, Peitz (2008) analyzed the entry deterrence effect of pure bundling for a multiproduct monopoly in a two dimensional Hotelling model. This is not a symmetric market. In his model, consumers are allowed to buy a bundle from the incumbent in addition of another product from the rival if the entry has occurred. Based on this assumption, pure bundling is preferred by the incumbent if the entry has happened. This differs from the result of Whinston (1990) where bundling is never preferred if the entry has occurred. In Peitz (2008)’s model, the horizontal axis had vertical axis represent consumers’ willingness to pay from buying product 1 and 2, respectively. A consumer located further from a firm means that this consumer has higher willingness to pay of buying this firm’s product hence she is more willing to buy its product. However, in our model, a consumer located further from a firm means that she needs to pay more cost to buy the firm’ s product, therefore she is less willing to buy its product. Based on Peitz (2008)’s model, the market configuration does not change as consumers’ reservation changes. Nalebuff (2004) also considered the similar problem by assuming the incumbent chooses prices before the entrant in a two dimensional Hotelling model similar to our model. But he did not examine the change of the level of consumers’ reservation. However in our study, market configurations change as consumers’ reservation changes and we assume consumers buy at most of each product. The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows. In section 2, the model and equilibrium in a monopoly market are introduced. In section 3 the model and equilibrium in a duopoly market are introduced. In section 4, we present a conclusion.

2. Monopoly Market

2.1. The Model

- Suppose there are two products, product 1 and product 2. They are provided only by firm A. We assume the marginal cost of either product is zero. Firm A has two strategies to select from, that is, bundling and independent pricing. Consumers purchase at most one unit of each product. Therefore, consumers are able to select at most four consumption combinations if firm A does not bundle, namely AA, A1, A2 and purchasing nothing. AA means buying products 1 and 2 from firm A; A1, A2 mean purchasing only a single product 1 from firm A, a single product 2 from firm A respectively. Similarly, consumers are able to choose to buy AA or to buy nothing if firm A bundles. A consumer purchasing one product will have a reservation value or reservation price of C, which is the highest price she is willing to pay. Therefore, a consumer will have 2C if she purchases two products. Consumers should be uniformly located in a Hotelling unit square with firm A located at (0, 0). In the unit square, product 1 is considered horizontally and thus as a consumer located further away from firm A horizontally, she holds less taste preference towards firm A’s product 1. Similarly, product 2 is considered vertically and as a consumer located further away from firm A vertically, she holds less taste preference towards firm A’s product 2. A consumer judges which combination she will buy by considering how much surplus she can get from purchasing each combination. Under an independent pricing scheme, a consumer located at (g1, g2) buying AA will get a surplus of 2C-λg1-λg2-p1A-p2A, where λ is the strength parameter of differentiation. p1A, p2A is the price of product 1 and product 2, respectively. Similarly, the consumer purchasing only a single product will get a surplus C-λgm-pmA, m=1, 2. When firm A bundles, the consumer buying the bundle will earn a surplus 2C-λ (g1+g2)-pA, where pA is the bundle price. We denote the profit under independent pricing as πAI, and the profit under bundling as πAB.

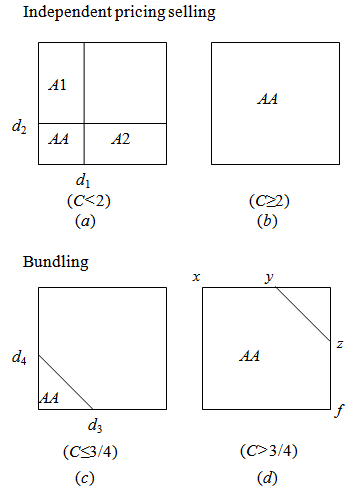

2.2. The Equilibrium Prices and Results

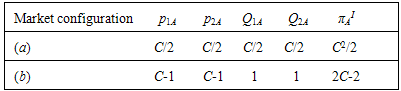

- Our model is an extension of Matutes and Regibeau (1988). However, as explained above, consumers are able to purchase a single product in our model and this enable us to consider the problem in a monopoly market.For simplicity of calculation, we set λ=1. We show the market configurations according to different levels of consumers’ reservation price (C) in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Market configurations in a monopoly market |

2.2.1. Independent Pricing

2.2.2. Bundling

2.2.3. Independent Pricing vs. Bundling

- To observe which strategy is preferred, we analyze three cases. Firstly, we compare the equilibriums in (a) and (c) when C≤3/4. Then we compare (a) and (d) when 3/4≤C<2. Finally we compare (b) and (d) when C≥2. After the comparison of the profits and prices in the equilibriums, we find that when C<0.86, independent pricing dominates bundling, otherwise bundling is preferred. In addition, we find that when C<21/2, pA< p1A+ p2A,, otherwise pA≥ p1A+ p2A.This result shows that the multiproduct monopoly may have different strategy according to different level of C. When C is relatively small, the firm has a stronger incentive to cut price if it bundles. In (a), decreasing the price of product 1 only increases the demand of product 1. Comparatively, in (c), decreasing the price of product 1 means decreasing the price of the bundle, and it will increase the demand of both products, thus pA< p1A+ p2A. However, this price cutting effect just works when C is small and there are many potential consumers in the market (the blanked area). Cutting the bundle price can attract potential consumers. Moreover, consumers have more varieties like A1, A2 such single product when the firm does not bundle. This enables the firm to attract many consumers that cannot afford two products, and this single product does not exist under bundling. Therefore, when C is small, πA B<πA I. As C increases, more and more people can afford to buy the products. And due to the price cutting effect, the potential consumers are less in the market of bundling compared with it in the market of independent pricing. However, as the potential consumers become less and less, cutting the price of the bundle will not increase the demand so much. Compared to cutting price to increase the demand, it is more profitable to increase the bundle price because the level of C is high enough to keep most people can buy the bundle. Similar to the price cutting effect, at this time, the incentive to increase the price under bundling is stronger than it under independent pricing. Thus p1A+ p2A < pA. Moreover, as C increases, more and more people can afford two products in the market of independent pricing, thus the advantage of product variety is weakened. Therefore, we have πA I<πA B.The price cutting effect disappears when there is a relatively small part of potential consumers under bundling, and then the firm chooses a higher price (which is higher than the sum of the prices in the market of independent pricing). Moreover, the price increases as C increases. Therefore, there is always a part of potential consumers feel difficult to buy the bundle. The market under bundling can never be fully served. Comparatively, under independent pricing, the price is always kept at a same level which is C/2 for each product. As C increases, the price increases and the market is gradually served more and more until fully served.

3. Duopoly Market

3.1. The Model

- Suppose there are two products, products 1 and 2, which can be used together or separately, such as coffee and sugar. There are two firms in the market, firms A and B, producing both products 1 and 2. Without loss of generality, all marginal costs are set to equal zero. A consumer purchases at most one unit of each product. Therefore, if both firms engage in independent pricing, nine system configurations are available for consumers to purchase, as follows: AA, BB, A1, A2, B1, B2, AB, and BA; otherwise, they purchase none. For example, AB means buying product 1 from firm A and product 2 from firm B and A1 stands for buying only product 1 from firm A. We examine the firm’ choice of pricing schemes by employing a two-stage game. In stage one, the firms decide whether to bundle. In stage two, the firms set their prices simultaneously. We extend the basic model of Matutes and Regibeau (1988), allowing consumers to purchase only one product. Consumers are uniformly distributed on the unit square: firm A is located on the origin (0, 0), while firm B is located at the point of coordinates (1, 1). The horizontal axis stands for product 1, and the vertical axis stands for product 2. Generally, under an independent-pricing scheme, a consumer buying only one product has a surplus of C - λdmj - pmj, where m = 1, 2, and j = A, B. The term C is the reservation value common to all consumers to buy one product. Therefore, buying two products will result in 2C. The term dmj is the distance between the consumer’s location and the firm j horizontally or vertically, which depends on the product m. The term pmj is the price of firm j’s product m, and λ > 0 measures the degree of horizontal product differentiation. We assume λ = 1 in this study. A consumer buying two products together has a surplus of 2C - λ(d1i + d2j) - p1i - p2j, where i, j = A, B. Concerning different pricing schemes, if a consumer buys both products from firm i engaging in pure bundling, she will have a surplus of 2C - λ(d1i + d2i) - pi, where pi stands for the price of pure bundling of firm i.

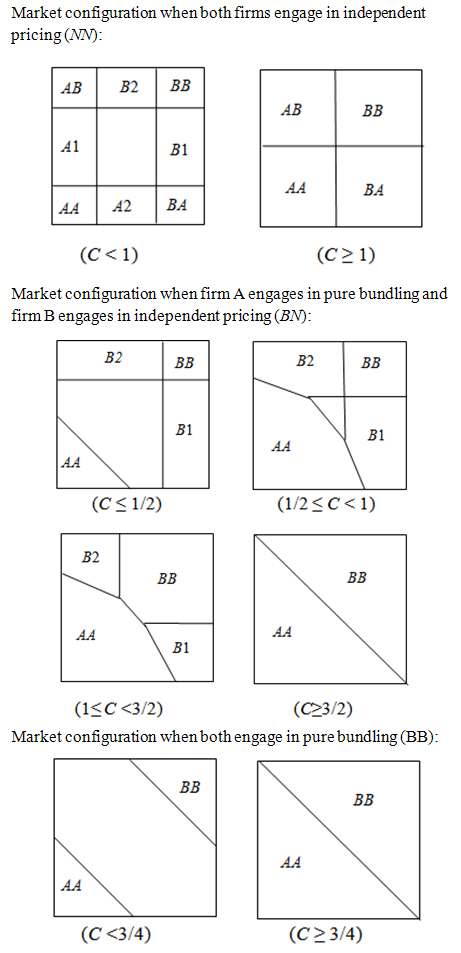

3.2. The Equilibrium Prices and Results

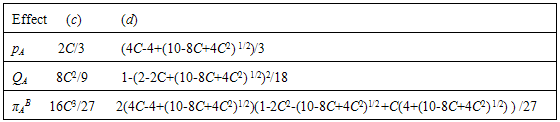

- The market configurations corresponding to different dimensions of C are presented in Figure 2. The three strategy combinations possible are BB, BN (NB), and NN. BB means that both firms engage in pure bundling. BN means only one firm engages in pure bundling, and we set the condition that firm A is the one that does so. NN is the combination that both firms do not bundle goods. Concerning the situation where only firm A bundles, we demonstrate an example for the calculation in the situation where C ≤ 1/2. The demand of AA on the horizontal and vertical axes are the same, and we denote demand as dmA, m = 1, 2, and 2C - dmA - pA ≥ 0 (i.e., dmA ≤ 2C - pA). Then, the area of the triangle is (2C - pA)2/2, and this is the demand for firm A. Therefore, profit is πA = pA (2C - pA)2/2. Maximizing firm A’s profit with respect to pA gives us maximized pA* = 2C/3 and πA* = 16C3/27. For other calculations, please refer to the Appendix.

| Figure 2. Market configuration in a duopoly market |

4. Conclusions

- We sought to analyze the incentive of bundling in both monopoly and duopoly market by considering the products are non-complementary. In a monopoly market, the results show that the incentive to bundle changes as conservation price changes. This reflects that the popularity of the products affects a monopoly’ s decision on bundling. This result has not been discussed in the previous work. In a duopoly market, we find that bundling may appear in the equilibrium. We did not discuss the welfare due to the complexity of calculation and this could be the future topic.

Appendix

- Monopoly market1. The market configuration of (a)Because the two products are independent, we can analyze them separately. In the market of product 1, we only consider horizontally. When the market configuration is as (a), the consumer (d1, 0) located in the boundary between to buy and not to buy A1 will earn a surplus of C- d1-p1A= 0 (i.e., d1= C – p1A). d1 is also the demand of product 1. Then we get the profit from market 1 is (C- p1A) p1A. Maximizing this profit with respect to p1A gives us maximized p1A = C/2, Q1A = C/2 and π1A = C2/4. Then we can conclude the result in the market of product 2 by considering vertically, and we get the same result of maximized p2A = C/2, Q2A = C/2 and π2A = C2/4. Therefore the total profit is πAI =π1A+π2A= C2/2. We can see that d1 = d2= Q1A = Q2A =C/2, when C=2, the market will be fully served to (b). 2. The market configuration of (b)In (b), considering the market of product 1, firm A sets a price to ensure all consumers (equal to 1) to buy product 1 thus C-1-p1A=0, and then we have p1A= C-1, π1A= C-1. Similarly, we have p2A = C-1, π2A= C-1. The total profit is πAI =π1A+π2A=2C-23. The market configuration of (c)In (c), the consumer (d3, 0) located in the boundary between to buy and not to buy AA in the horizontal line obtains a surplus of 2C –d3 – 0 – pA = 0 (i.e., d3=2C - pA). Similarly, we have d4 = 2C - pA in the vertical line. Then, the area of the triangle is (2C - pA)2/2, and this is the demand QA for firm A. Therefore, the profit is πA = pA (2C - pA) 2/2. Maximizing firm A’s profit with respect to pA gives us maximized pA = 2C/3, d3= d4=4C/3, QA =8C2/9 and πAB = 16C3/27. We can see that d3= d4=4C/3, when C=3/4, the market will change to (d). 4. The market configuration of (d)In (d), for the consumer located at (y, 1), her surplus is 2C-dxy-1- pA =0, then we get dxy=2C-1-pA. Similarly we gave dzf=2C-1-pA. Therefore the total demand QA is 1-(1-(2C-1-pA)) 2/2, and the profit is pA(1-(1-(2C-1-pA)) 2/2). Thus we have the maximized pA = (4C-4+(10-8C+4C2) 1/2)/3, dxy=dzf=(2C+1-(10-8C+4C2)1/2)/3,QA=1-(2-2C+(10-8C+4C2)1/2)2/18 and πAB=2(4C-4+(10-8C+4C2) 1/2)(1-2C2-(10-8C +4C2) 1/2+C(4+(10-8C+4C2) 1/2) ) /27. Because we find dxy = dzf = (2C+1-(10-8C+4C2) 1/2)/3<1 always regardless of the level of C, thus as C increases, the market can never be fully served.Duopoly market The derivations of “both engage in pure bundling” can be found in Matutes and Regibeau (1988). Because there are a great number of market configurations and the ways of calculations are similar, we show two examples of how we derived the outcomes.(1) When 1 ≤ C < 3/2, it is an adjacent market of NN in case 1, where the market boundary of AA and AB just touches, and the market boundary of AA and BA just touches. Since the market 1 is separated from market 2, therefore the market boundary of A1 and B1 just touches, A2 and B2 just touches. In an adjacent market, both firms set prices for their complete systems so as to leave consumers located at the common market boundary with exactly zero surplus. The markets of a certain product are symmetric, thus we have:C-1/2-p1A = 0, C-1/2 -p1B = 0, C-1/2- p2A = 0, C-1/2-p2B = 0, so we have p1A = p1B = p2A = p2B = C-1/2. πA = p1A/2+p2A/2 = C-1/2, πB = p1B/2+ p2B/2 = C-1/2.(2) When 1/2 ≤ C < 1, we consider the market where only firm A engages in pure bundling in case 1. First, we can find the critical point where buying AA is indifferent from buying B2 for the consumer (0, g2): 2C- pA- g2=C-p2B-(1- g2),, so g2= (C+ p2B +1- pA)/2. Similarly we can find other critical points located on the axis. In addition, we can find the line where AA is indifferent from B2, where 2C- pA- g1- g2 =C-(1- g2) - p2B, so g1 = (1+C+ p2B- pA -2g2). g1, g2 stand for the consumers located on the line in the unit square horizontally and vertically, respectively. We find the demand for each firm by using the critical points and indifference lines. The first order conditions are: (A) (-9C2-3 p1B 2-(1+ pA)2-4 p1B (3+ pA)+2C(5+6 p1B +3 pA))/4(B) (-9C2-3 p2B 2-(1+ pA)2-4 p2B (3+ pA)+2C(5+6 p2B +3 pA))/4 (C) (-2-10C2- p1B 2-2 p2B - p2B 2-8 pA -4 p2B pA -2 p1B (1+ pA)+2C(6+3 p1B +3 p2B +4 pA))/4The equations of (A) (B) and(C) can be solved by computer for several values of C.

Note

- 1. Strictly speaking, when C approaches 1.4, say C = 1.48, only NN becomes the equilibrium.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML