-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

2012; 1(1): 1-11

doi: 10.5923/j.m2economics.20120101.01

Remittances Effect on Poverty and Social Development in Mogadishu, Somalia 2009

David Lameck Kibikyo 1, Ismail Omar 2

1Centre for Basic Research (CBR), Kampala, P. O. Box 9863, Uganda

2Mogadishu University, Mogadishu, Somalia

Correspondence to: David Lameck Kibikyo , Centre for Basic Research (CBR), Kampala, P. O. Box 9863, Uganda.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

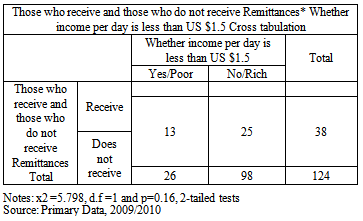

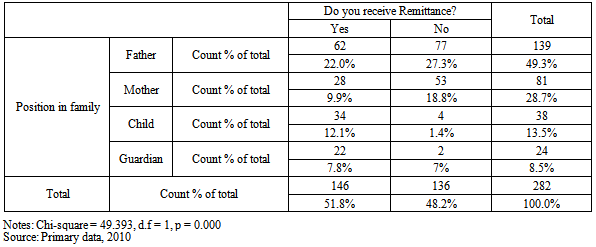

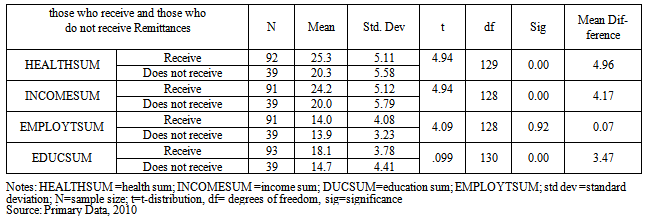

While studies exist on remittances on poverty in Somalia, they have not only been qualitative but also ignored the effect these remittances have on poverty, health and education. We investigate the remittances impact on poverty and social development on recipients in Mogadishu City in 2009. We use data of 300 questionnaires collected from Mogadishu residents in July 2009 from remittances recipients and non-recipients. Remittances, poverty and social development are measured using five-point likert scale. Data is analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. The quantitative analysis investigates impact on remittances on poverty, education and health, incomes and employment using differences between means, chi-square and regression analysis. The results indicate that remittances lived up to their expectation of poverty reduction; boosted incomes, education and health; but failed to impact on employment. The study recommends addressing employment policies related to remittances.

Keywords: Remittances, Poverty, Social Development, Gender, Mogadishu, Somalia

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Although the economy in Somalia is largely dependent on remittance, its contribution to Human Development is unknown despite its spectacular growth and prevalence as the engine of national economy during anarchy. Studies by Maimbo (2006); Kulaksiz and Purdekova (2006); Lindley (2006); Waldo (2006) on remittance on Somalia acknowledges the increased volumes but equally questions the role of remittance in Human Development given the un reasonably low Human Development levels. It is against this background that this study investigated the effect of remittances on Human Development in Somalia. The spectacular increase in remittances is not unique to Somalia alone but general to entire LDCs.Since 1980s, developing countries (LDCs) have witnessed a unique rise in workers’ remittances. The World Bank (2006) estimates, official remittances received by LDCs increased from US$31.2 billion in 1990 to US$221.3 billion in 2005, representing an annual growth rate of over 13 percent. Remittances are now equivalent to about 35 percent of total financial flows to developing countries and have surpassed both official development aid (ODA) and non-foreign direct investment (FDI) flows, interestingly. These figures exclude unrecorded remittance flows estimated to be at least 50 percent higher. While reasons for migration differ international, for Somalia it was anarchy. In Somalia the cost of civil conflict and absence of a state in economic and social development has been extremely high especially on employment, health and education. Today, 47 percent of the economically active population is unemployed in Somalia. Health infrastructure is dilapidated or non-existent, health care only sparsely provided and enrolment rates in schools are the lowest in the world (Kulaksiz and Purdekova, 2006). The UNDP Human Development report of Somalia (2001) explains the economic decline and civil war in the 1980s and protracted armed conflict in the 1990s caused poverty levels, deprivation and vulnerability reflected in Somalia’s declining Human Development Index (HDI) were life expectance stood at 47 years, infant mortality rates stood at 132/1000, maternal mortality rates stood at 1600/10000, primary school general enrolment stood at 13.6%, adult literacy stood at 17.1% and GDP per-capita stood at US$795. Maimbo (2006) reports that Somalia has long been a failed state and one of the poorest countries in the world with a population of 7.3 million in 2004, and an income per capita of US$226. Health infrastructure is dilapidated or non-existent, health care is only sparsely provided and school enrolment rates are the lowest in the world. Similarly, extreme poverty defined as the proportion of population living on less than US$1.5 per day measured at purchasing power parity (PPP) for international comparisons and aggregation is estimated as 43.2 percent. The extreme poverty in urban areas is 23.5 percent and in rural and nomadic areas stood at 53.4 percent. In absolute terms, the population living in extreme poverty is estimated as 2.94 million people, consisting of 0.54 million in urban and 2.4 million in rural and nomadic areas (World Bank report on Somalia, 2003). Interestingly, despite the anarchy, few indicators display a bad situation not only maybe due to remittances but also suggesting that despite insecurity things were improving compared to seven years ago.First, despite the anarchy, only two out of the 18 development indicators, adult literacy and combined gross school enrollment, show a clear welfare decline under stateless. Given that foreign aid was completely financing education in Somalia pre-1991, it is not surprising that there has been some fall in school enrollment and literacy. This is less a statement about the Somali government’s ability to generate welfare enhancing outcomes for its citizens than it is a reflection of foreign aid poured into Somali education by the international development community before anarchy (Leeson, 2010). Second, much of the credit for Somalia’s improved development belongs to its economy, which has been allowed to flourish in the absence of government predation. Although economic advance has been uneven, in some areas, the local economy is thriving and is experiencing a unique economic boom. Somalia’s cross-border cattle trade with Kenya is particularly instructive of this progress. Livestock is the most important sector of the Somali economy. It constitutes an estimated 40 percent of Somalia’s GDP and 65 percent of its exports (CIA World Fact book, 2006). Somalia’s “private sector has proved to be a relatively effective provider of key social services, such as water or transport” (UNDP, 2001). Today, transportation for freight and people connects even the smallest villages in Somalia to major urban centers, and is relatively cheap (Nenova, 2004). A state-owned (SOEs) electricity provider opened in Hargeisa in 2003 although, most Somali electricity is privately provided. Water needs are also supplied by private firms (Ahmed, 2000; UNDP, 2001).Relating Remittance to Poverty and Social DevelopmentThe term “remittances” refer to the transfers, in cash or in kind, from a migrant to household residents at home. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has a broader definition and include three categories, namely: (i) worker’s remittances or transfers in cash or in kind from migrants to resident households at home; (ii) compensation to employees or the wages, salaries and other remuneration, in cash or in kind, paid to individuals who work in a host country; and (iii) migrant transfers which refer to capital transfers of financial assets made by emigrants as they move from one host country to another and stay for more than one year (Akkoyunlu and Vickerman, 2000).Brown and Ahlburg (1999) official and unrecorded remittances include money transfers sent via the formal banking system to households; money transferred informally in cash (bills) or via an informal agent to households; the value of all goods sent to households; payments made by the migrant on behalf of households; donations by the migrant to other institutions or organizations; and deposits made into bank accounts held by the migrant overseas. Also migrants may remit to other institutions and organizations, mainly churches (Brown and Walker, 1995). Donations are often collected by the churches or mosques in the host countries and are held in bank accounts there, to be transferred overseas or used to settle international payments on behalf of the church in the country of origin. In the next section, remittances can be understood for purposes of providing for basic needs, as an insurance cover in old age or as a loan agreement.Are Remittances Insurance or Loan Agreements? According to the altruistic motive theory by Stark (1991) the common belief is that migrants remit for the purpose of family consumption support which may include education, health, cash at hand, and investments. The total amount remitted is disaggregated into separate parts, each being driven by a different motivational characteristic (Stark, 1991). For example, Brown and Walker (1995) and Brown (1997) found strong evidence that migrants can be motivated to remit for reasons of saving and investment at home including investment in education of the next generation (Brown and Poirine, 1997). Besides ordinary consumption, other theories exist that have basis in old-age insurance.Rapport and Docquier (2006) the unit of analysis is the family, which acts initially as the insurer, investing in the education and establishment costs of the migrant family member. There is also an element of self-interest in the migrant honoring the contract. On the migrant’s eventual return home, she might expect to become a beneficiary of family inheritance. At retirement the ex-migrant possibly also becomes a recipient of remittances from the family’s subsequent cohorts of migrants, especially if some of her remittances had financed the education of the younger cohorts of migrants in the family. Poirine (1997) refutes Stark’s postulate and advances instead an approach that he terms, an informal loan agreement. For Poirine, remittances have to be understood in the context of various implicit loan agreements between the migrant and non-migrant family members through which investment in migrants’ human capital is loaned and later repaid by the employed migrant. The would-be migrant “borrows” to finance her education before migrating. The subsequent remittances can then be considered “loan repayments” to the family. Later, the migrant remits, not as a loan repayment, but as part of a “loan advancement” to finance the education of the next cohort of potential migrant members of the family. Finally, after the migrant has returned home, she becomes a recipient of remittances which constitute the implicit “repayment” of that loan. Remitters, Recipients and AgentsDavis (2005) indicate that the interest generated by the increasing volume of remittances has brought financial institutions such as, commercial banks, credit unions, and micro finance institutions (MFIs) into the remittance market. The growing attention to the issue of remittances and the consolidation of the industry translates into greater competition for the remitters’ business. Consequently, the remitters can now expect better service at a lower cost.Effect of Remittances A number of theories explored attest to the fact that remittances do not only have impact on poverty but also on social development such as education and health.Effect of Remittances on PovertyPoverty in its most general sense is the lack of necessities. Extreme poverty is the proportion of population living on less than 1.5 US $ per day measured at purchasing power parity (PPP) for international comparisons and aggregation (World Bank, 2010). Basic food, shelter, medical care, and safety are generally thought necessary based on shared values of human dignity. However, what is a necessity to one person is not uniformly a necessity to others. Needs may be relative to what is possible and are based on social definition and past experience (Amartya Sen, 1999). Valentine (1968) argues that “the essence of poverty is inequality. The basic meaning of poverty is relative deprivation. Poverty according to the federal government as the annual income needed for a family to survive. The “poverty line” was initially created in 1963 by Mollie Orshansky at the U.S. Department of Agriculture based on three times her estimate of what a family would have to spend for an adequate but far from lavish diet. According to Michael Darby (1997), the very definition of poverty was political, aimed to benchmark the progress of poverty programs for the War on Poverty. Adjusted for inflation, the poverty line for a family of four was $17,050 income in 2000 according to the US Census. Most poverty scholars identify many problems with this definition related to concepts of family, cash income, treatment of taxes, special work related expenses, or regional differences in the cost of living (Blank 1997; Quigley, 2003). This study measures poverty as earning and leaving on less than US$1.5 per day. Remittances impact on poverty is both micro as well as macro.ImpactOn a micro-level, remittances provide fundamental sources of income for the recipients. While they have no impact on income gap between developed and developing countries, they directly contribute to economic growth of local communities providing a much needed stability. Rural households who benefit by approximately one third of total remittances reinvest almost every dollar received to serve basic needs like food, medicines and clothing (Adams, 2006 and UN News Center, 2007). These aspects are important ingredients of poverty. The multiplier effect is at its maximum and local markets thus fully profit from the social returns of these investments. Once basic needs are served, remittances amounts will be spent in education which, on the long-term, will bring positive effects to local economies. Richer households will use remittances for entrepreneurship purposes bringing social benefits in most circumstances. The impact on the economy, however, depends on the receiving country and its local population’s propensity to save or invest. According to the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), 10-20 per cent of the amount received is saved at home, creating a missed opportunity for local growth (IFAD, 2007).Benabou (1996) suggests that remittances are more likely to increase human development in poor countries provided they reach poor households. In fact in this context remittances may be viewed as direct transfer, substituting for the perhaps less efficient tax base or foreign aid based redistribution schemes. This hypothesis is testable to the extent that remittances raise growth and investment and savings rates in economies that have significant inequality, poverty and where transfers do appear to reach the poor 20% or 40% of the population.The analysis of poverty impact of remittances must account for counter-factual loss of income that the migrant may experience due to migration, if the migrant has to give up her job. Such losses are likely to be small for the poor and unemployed, but large for the middle- and the upper-income classes. Very poor migrants may not be able to send remittances in the initial years after migration. Also the remittances of the very rich migrants may be smaller than the loss of income due to migration. But for the middle-income groups, they enable recipients to move up to a higher income group. In Sri Lanka, households from the third through the eighth income deciles moved up the income ladder due to remittances (Ratha, 2007). Besides the micro effects, remittances were capable of setting off macro impacts.The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) argues that remittances are much more effective than aid, which suffers directly from both grand and petty corruption, bureaucratic delays and are sometimes invested in inferior projects. On the contrary, remittances are not “direct investments” in local households which are bereft of the already stated problems nor do they suffer directly from booms and slumps like aid does. Accordingly, when conflicts happen in origin countries, remittances make available a vital lifeline, interestingly not provided by local governments (Adams & Page, 2003). Macro-Economic Effects of RemittancesDavis (2005) noted that in Jamaica with the steady growth of money transfers, the social and economic impact of remittances has moved beyond the sphere of households, increasingly played an important role in the economic performance with potential multiplier effect on GDP, consumption and investment. Further, the Diaspora provides several other important sources of revenue and economic activity to their home countries. Remittances expand the tourism industry and related economic sectors such as airlines and other forms of transportation through regular visits home. Remittances also enhance purchasing products from home while living abroad thereby stimulating growth in ‘nostalgic industries. Migrants’ remittances also cause investment in small businesses in their home countries; and provide financial support to facilitate development and philanthropic initiatives at home. Whether invested or consumed, remittances have important macroeconomic impacts generating positive multiplier effects, while stimulating various sectors of the economy. Adelman and Taylor () show that for every dollar Mexico received from migrants working abroad, the GNP rose by $ 2.69 to 3.17 depending on where the remittances were received either urban or rural households (Rathe, 2003). Other studies analyzing links between remittances and poverty in Ghana (2005) suggest that raising remittance by 10 percent decreases the share of those in poverty by 3.5 percent and has a negligible impact on income inequality, as measured by the GINI coefficient (Adams, 2005). Ratha (2003) studying of 74 low and middle-income countries suggests that the impact of remittance flows on the poverty headcount might be smaller on average (Adams and Page, 2003). The point estimates for the poverty headcount measure using survey mean income suggest that a 10 percent rise in share of remittances in GDP will cause a 1.6 percent decline in the poverty headcount ratio (people living on less than $1/day). The point estimate for the poverty gap and severity of poverty (poverty gap squared) suggest that on average, a 10 percent rise in share of remittances in GDP will cause a two percent decline in depth and severity of poverty. The effects of remittances on poverty were under estimated in the last study because in measuring remittances; the large unknown amount remitted through private, unofficial channels is excluded.Ratha (2007) argues that remittances directly augment the income of the recipient households and indirectly affect poverty and welfare through indirect multiplier effects and also macroeconomic effects. Cross-country regression analysis also show significant poverty reduction effects of remittances: a 10% increase in per capita official remittances may lead to a 3.5% decline in the share of poor people. Remittances reduced poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and Latin America, although with mixed effects across countries. Household survey data show that remittances reduced the poverty headcount ratio significantly in several low-income countries by 11 percentage points in Uganda, 6 percentage points in Bangladesh, and 5 in Ghana. In Nepal, remittances may explain a quarter-to-half of the 11 percentage point reduction in the poverty headcount rate since 1997. The extent of poverty reduction depended on social class of the migrant.Home governments have introduced a variety of schemes for migrants with several policy objectives in mind; namely, repatriatable foreign exchange accounts to encourage the greater use of official channels, foreign currency denominated bonds to encourage more use of financial assets in the home country, and self-employment investment schemes to stimulate more direct investment in productive assets. In other instances governments have resorted to mandatory remittance ratios, requiring migrants to remit a given percentage of their foreign earnings through the official channels, and hence to be converted to domestic currency at the official exchange rate. In order to encourage migrants to hold their savings balances in financial assets in their “home” as opposed to host countries many governments have introduced foreign currency denominated bonds (Maimbo, 2003). Another policy area concerns schemes to encourage migrants themselves to become investors. There is substantial scope for policy intervention on the part of Asia Pacific island governments wishing to increase the flows of remittances to their economies. All the evidence suggests that migrants’ remittances would be responsive to financial incentives of the sort that have been adopted elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region to promote migrants’ remittances (Buencamino and Gorbunov, 2002). Generally, these policies have not been effective.It is generally accepted, however, to encourage the use of remittances to policies to promote longer-term growth and income security in home economies have been a failure. The belief is that policies can be effective in encouraging migrants to: channel more remittances through official, rather than informal channels; increase their levels of remittances by encouraging them to hold their savings in financial assets in the home rather than host countries; themselves become investors in productive assets in the domestic economies of the home countries (FATF, 2003).Effect of Remittances and Social Development The UNDP (1990) lists two elements of Human Development to include social development and poverty levels measured by the Human Development index (HDI). The HDI is a composite statistic used as an index/glossary to rank countries by level of "human development" andseparate developed (high development), middle development, and low development) countries. The statistic is composed from statistics for Life Expectancy, Education, Standard of living and GDP collected at the national level.Migrants sometimes also make payments on behalf of relatives or others at home for social services, investments or for the purpose of acquiring assets there on their own behalf (Brown, 1997). These could be financial savings deposits with banks, or other physical assets such as land, housing, farm equipment and supplies and inventories for small businesses.Remittances are used for various forms of investment, sometimes in the agricultural sector but more frequently in the service sector, and especially into stores and transport businesses. There is some evidence that remittance money has constituted the start-up money for many small shopkeepers. Walker and Brown (1995) indicate a significant proportion of remittances received by Tongan and Samoan households were used for “business and farm investment.Remittances are associated with increased household investments in education, entrepreneurship, and health all of which have a high social return in most circumstances. Studies based on household surveys in El Salvador and Sri Lanka find that children of remittance recipient households have a lower school drop-out ratio and that these households spend more on private tuition for their children. In Sri Lanka, the children in remittance receiving households have higher birth weight, reflecting that remittances enable households to afford better health care. Several studies also show that remittances provide capital to small entrepreneurs, reduce credit constraints and increase entrepreneurship (Ratha, 2007).Lucas and Stark (1985) argue that if remittances are effectively a repayment of past expenditure by family in the migrant’s education, the level of remittances can be expected to be positively related to human development improvement.

2. Main Body

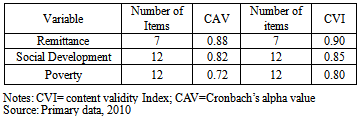

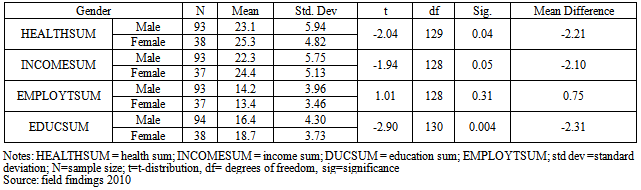

- A questionnaire was used to collect primary data. Its reliability and validity were also tested. Self administered structured questionnaire was designed and administered to obtain the required information. The study used a standard questionnaire with both closed and open ended items scored on a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from 5 for strongly agree to 1 strongly disagree. The questionnaire was tested for reliability and validity using Cronbach’s alpha to test if the variables used in the questionnaire consistently measure what they are supposed to do. Alpha coefficient values of 0.70 accepted as the minimum accepted for social sciences. The reliability results are presented in table 1.

|

|

|

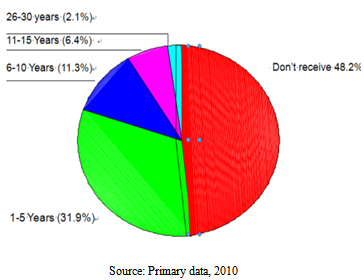

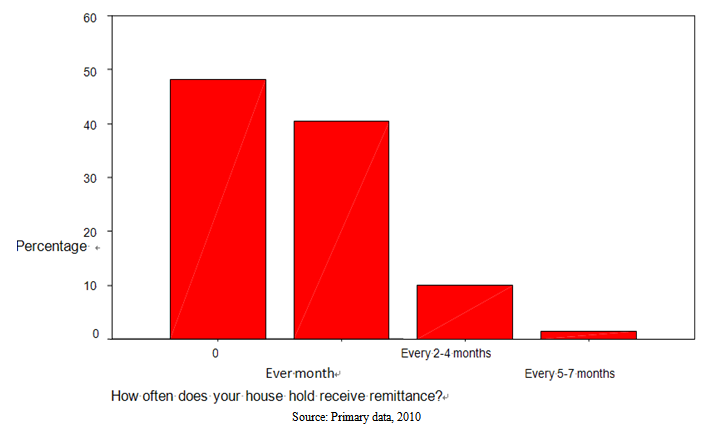

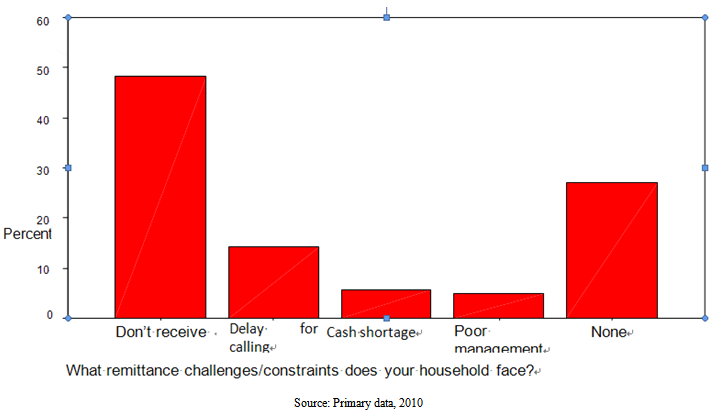

| Figure 1. Duration and Frequency of remittance by the respondents |

| Figure 2. How often the respondents received remittance |

| Figure 3. Constraints/Challenges in accessing remittance |

|

|

|

2.1. Education

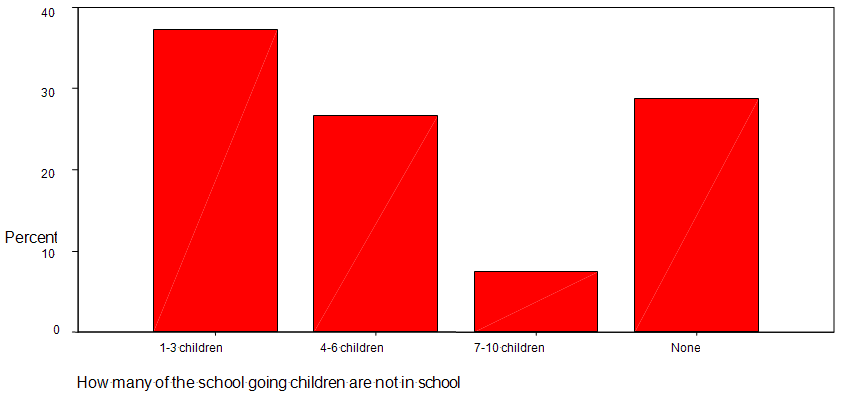

- Miambo (2006) and Lindley (2006) writing about Somalia noted that the remittances received by a substantial minority of city-dwellers improve their economic status and access to education. It often plays a central role in the livelihoods of the recipients and help finance education, in some cases allowing the family to choose high cost forms of education. Children in the households of people receiving remittances have relatively better school attendance rates. Moreover migrants often encourage families to whom they send money to educate their children. Sibling solidarity plays a particularly crucial cultural role in the education and welfare of children and young people.There are more primary schools in Somalia today than there were in the late 1980s under government, and this number is growing rapidly (UNDP, 2001). The number of formal schools has increased from 600 in 1990 to 1,172 under statelessness. There are many Koranic schools as well that focus mostly on the Koran and learn Arabic. Higher education has similarly benefited by statelessness. There was only one university in Somalia prior to the emergence of anarchy. Under statelessness universities have sprung up in Borama, Hargeisa, Bossaso, and Mogadishu. These universities offer subjects from computer skills to accounting. According to UNICEF, although the state of education in Somalia remains poor, there is evidence of gaining momentum in the education sector and improving children’s literacy and numeracy (UNICEF, 2005). The study equally sought to establish the number of children out of schools and the findings are presented (figure 7).Source: Primary data, 2010Figure 7 above shows that most respondents (37.2%) indicated that 1-3 children were not enrolled in school while 26.6% indicated that they had 4-6 children not enrolled in school and 7.4% indicated that 7-10 children were not enrolled in school although a reasonable percentage of 28.7% indicated that none of the children in the households were out of school. This study finding generally revealed that a reasonable number of children were not enrolled in school due to some constraints which this study strived to establish and the findings are shown in figure 8.

| Figure 7. Number of children out of school in Mogadishu, 2009 |

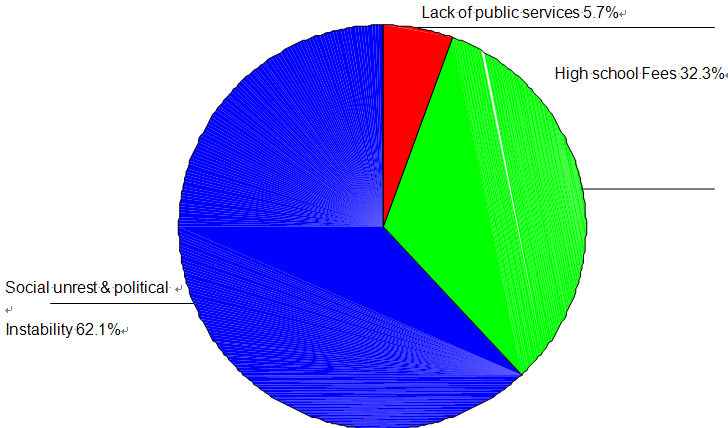

| Figure 8 shows that a majority of 62.1% indicated that social unrest and political instability was constrained |

|

2.3. Health

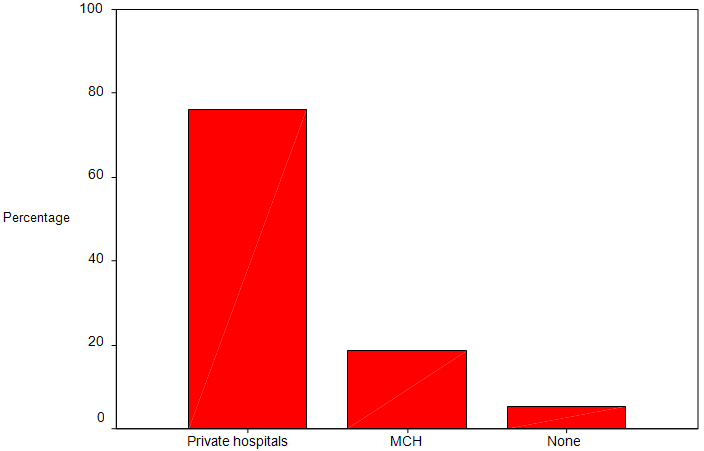

- Somalia’s “private sector has proved to be a relatively effective provider of key social services, such as water or transport” (UNDP, 2001). Today, transportation for freight and people connects even the smallest villages in Somalia to major urban centers, and is relatively cheap (Nenova, 2004). A state-owned (SOEs) electricity provider opened in Hargeisa in 2003 although, most Somali electricity is privately provided. Water needs are also supplied by private firms. Private social insurance provides a safety net financed through impressive remittances from abroad. These remittances average $4,170 annually per household estimated to be 25-60 percent of household income (Ahmed, 2000; UNDP, 2001). Figure 9 above shows that a total of 76.2% of the respondent sought treatment from private hospital or health centres while only 18.4 sought treatment from Mogadishu central Hospital. Some (5.3%) received no treatment at all whenever they fell ill. Health services delivery was mainly sought from private service providers explained by its cheapness. Although the state of medicine in Somalia remains extremely low, medical consultations are very affordable ($0.50/visit). Further, the percentage of Somalis with access to a medical facility has nearly doubled since 1989-1990 before statelessness emerged. Privately-provided public goods like “education and health care services and utility companies such as electricity and water, are also providing new income generating and employment opportunities” that further contribute to the growing Somali economy (UNDP, 2001).

2.4. Employment

- Remittances have strong positive impacts on the current account balance of Somalia but could also be negative such as the Dutch disease effect. Although remittances as foreign savings allow Somalia, a country without access to international capital markets, to consume outside its production frontier, these inflows might also draw resources from tradable to non-tradable sector, worsening the welfare of families that do not benefit from remittances (Ratha, 2007).

| Figure 9. Providers of Health Services in Mogadishu 2009 |

Appendices

|

|

3. Conclusions

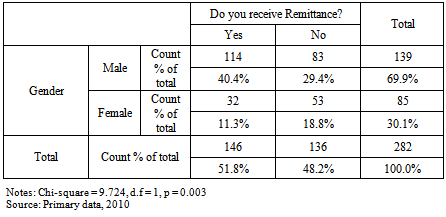

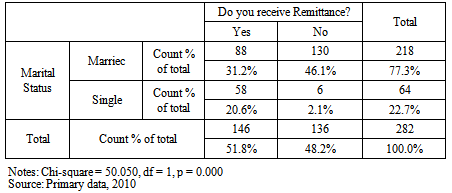

- The study investigated the remittances impact on poverty and social development on recipients in Mogadishu town in 2009. We use data of 300 questionnaires collected from Mogadishu residents in July 2009 of those who receive and do not receive remittances from abroad. Remittances, poverty and social development are measured using five-point likert scale. Data is analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. The quantitative analysis investigates impact on remittances on poverty, education and health, incomes and employment using differences between means, chi-square and regression analysis. The results indicate that remittances lived up to their expectation of poverty reduction; generation of incomes, supporting education and health but failed to impact on employment. The study recommends that for remittances to sustainably eradicate poverty, policies for employment generation needed to be addressed.EndnotesThe HDI combines three dimensions: Life expectancy at birth, as an index of population health and longevity Knowledge and education, as measured by the adult literacy rate (with two-thirds weighting) and the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrolment ratio (with one-third weighting). Standard of living, as measured by the natural logarithm of gross domestic product per capita at purchasing power parity (Haq, 1990). In advancement of the Human Development index, the UNDP has developed a more detailed indicators to include GDP (PPP constant $); life expectancy (years), one year olds fully immunized against measles one year olds fully immunized against TB (%), physicians (per 100,000), improved, infants with low birth weight (%), improved, infant mortality rate (per 1,000), maternal mortality rate per, population with access to water (%), population with access to sanitation (%), population with access to at least one health facility (%), extreme poverty (% < $1 per day), radios (per 1,000), telephones per1,000), TVs (per 1,000), fatality due to measles, adult literacy rate (%), combined school enrolment (%).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML